Anecdotal analysis of the differences between Chinese and western cultures

Chinese cultural roots and traits, the underlying drivers of the Chinese mental and behavioural patterns, were discussed in Chapter 4.1. When examining cultural differences, note should also be taken of the fact that China is moving towards a more open society and increased interaction of Chinese people with westerners has prepared the ground for acceptance of western management concepts and practices. Table 4.2.1 is a list of key differences in the business context between Chinese and western cultures.

| Chinese culture | Western culture |

|---|---|

| Large power distance Reverence to rank and power Bureaucracy | Small power distance Equality among people Authority of law |

| Strong tendency of risk avoidance Dominance of group interest and values Doctrine of the mean and ambiguity Resistance to change Lack of original creativity | Strong tendency of risk taking Dominance of individualistic interest Clarity in expression Acceptance of change Pro-innovation |

| Pursuit of moral accomplishments Cultivation of personal virtue Despise material gains 'Face' is important Connotation and tolerance | Pursuit of objective being Knowledge and skill learning Recognition of material gains 'Face' is unimportant Candour and rigidity |

Of course, this list is not exhaustive and many others can be added to it from different perspectives and experiences. The differences identified here are more relevant to the business environment than to personal traits. They are not only key variables of Chinese 'collective mental programming' (Hofstede) process, but also the determinants of conflict management behaviour.

Power distance, one of Hofstede's measures of cultural difference, is one of the most prominent differences of Chinese culture compared to that of the west. The Confucian cultural and social traditions dictate a rigid social hierarchy “ top-down control and distribution of power by rank, as a result of which bureaucracy is seldom challenged and reverence to rank and power is considered to be a virtue. The results of power distance are often manifested in a lack of efficient vertical communication, obedience in execution of the orders/ instructions of the superior and avoidance of a direct challenge to power. The top-down control structure makes many Chinese organisations resemble the personal characteristics of the top leader.

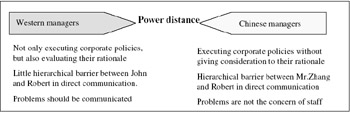

In the context of a joint venture, power distance is also at play. Open argument with the management about, for example, corporate strategies, is rarely seen. Private, one-on-one meetings may encourage a Chinese manager to speak more freely about his opinion. Foreign managers should be careful with their mode of expression when challenging the ideas of Chinese managers who hold superior positions .

Power distance does not only exist within an organization. It is omnipresent in the web of the social hierarchy. The mental programming process in handling power distance is situational and involves complex considerations, among which 'face' is an important factor. Whether or not a person in an organisation will challenge the ideas of another person depends on his judgement of the 'face' element as well as the other person's rank in the hierarchy. He is less likely to challenge his superiors and likely to challenge others of the same rank. Face is less of an element of consideration when dealing with underlings, but face-giving is also a lubricant of power distance in a bottom-up direction. For example, the Chinese have a tendency to credit the successes of corporate achievements to the supervising authority or government departments, a face-giving effort to minimize obstacles resulting from power distance. This, amongst other things, often causes 'culture shock ' in foreigners. A German engineer, leading a group of technicians to install the equipment contributed by the German partner in China, was bewildered when he heard at the opening ceremony of the joint venture, that the successful commissioning and operation of the equipment was credited to 'the correct leadership' of the supervising authority and his team's effort in making equipment running was not acknowledged . When he learned that it was a rhetoric formality to mention the supervising authority, he copied this exercise when the equipment failed and announced that the equipment went wrong due to the leadership of the supervising authority. Everyone present was taken aback.

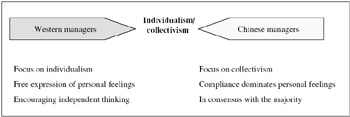

The story of the German engineer reflects not only a lack of understanding of cultural context, but also the differences between Chinese and western culture in terms of the emphasis on group and individual contribution. China is generally a collectivist society. Individualism- collectivism, another of Hofstede's dimensions of culture, is an important parameter in measuring cultural variability, as it shows the norms and values that a culture attaches to social relationships and social exchanges. The Chinese people have a tendency of pursuing collective goals rather than individual interests, and this is a fundamental characteristic of the Chinese culture governing the relationship between organization and individuals. Collectivism is still emphasized in China as a virtue and a citizen's social responsibility. In the official doctrine of collectivism, individualism is regarded as egoism or a source of selfish desire and is therefore suppressed for the common well-being. However, over the past 24 years since China opened up to the outside world, the collectivism tendency has been exposed to western individualism , and its influence is clear among the younger generation, who have a stronger sense of self-importance.

In a business environment, collective consensus is often sought in the decision-making process, although power distance may block different opinions . Managers often speak of collective interests to hold back individual desire, whereas the individual aspirations are often achieved in the name of collectivist pursuit. In addition to this, collectivism underlies egalitarianism in welfare and income distribution. An extreme example of this egalitarianism is a Chinese scholar who won a prize for his remarkable achievements but divided his prize money between not only his leaders and team members , but also people irrelevant to his work such as drivers and cooks. He attributed his success to the leaders at the top of the organization for their support and those at the bottom of the structure for their logistical support. Although this egalitarianism is weakening following Deng Xiaoping's advocacy of 'let some people get rich first', this inclination towards egalitarianism driven by collectivism should be taken into consideration in managing employee relations.

Where collectivism seems to correlate with the western management practice of teamwork is that people of a collectivist culture prefer to work in groups rather than individually. Although the Chinese characteristic of collectivism prepares the ground of team spirit in some ways, it still represents a departure from what teamwork requires. The lack of horizontal communication, tendency to work only with peers, reluctance to share knowledge and mistrust among co-workers arising from the lack of explicit expression need to be carefully handled before teamwork and team spirit can be established.

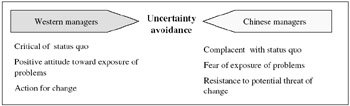

To fit the Chinese culture into Hofstede's uncertainty avoidance dimension is difficult, because the tendency of uncertainty avoidance in Chinese culture is high in some cases and low in others and so some researchers put China into the low category; others in the high. (The authors wish to avoid uncertainty by not making this judgement.) Typically, Chinese people have a tendency to avoid risks, resist changes, tolerate contradictions, accept ambiguities , pursue cultivation of virtue rather than truth, observe informal rules (affective) and compromise on formal rules (instrumental). In a business context, the tendency of risk avoidance often leads to a different understanding of change, while tolerance of contradictions leads to different paths of conflict resolution. Ambiguity in expression as a typical feature of a high-context culture often makes cross-cultural communication ineffective . Ambiguity in Chinese culture comes from the contextual and dialectical thinking which contrasts with the westerners' linear thinking patterns.

Let us take a look at a case of cultural differences in a joint venture, which will help understand how some of Hofstede's culture dimensions are at play in a corporate environment.

Case study

The company is a joint venture between an overseas Chinese and Western entrepreneur, operating in China with the Chinese holding the majority shares. After 10 years of development, the venture has become a multi- million dollar business and it is still growing. The company's marketing department consists of three teams . Interestingly, each team has the same function as the other, which is basically to solicit customers and provide 'tailor-made' services. To encourage teamwork, the company staged an incentive system that provides performance- related bonuses.

The outcome of the incentive system was both positive and negative. On the positive side, a competitive environment was established and sales increased. However, teams began to compete against each another for customers and hostility later arose among the teams. John, a marketing assistant, observed the development and communicated his concerns and observations to Robert, the company's western partner and vice-president with responsibility for marketing. This is a summary of his points:

-

The three groups are competing against each another for clients and blocking client information

-

There is an unwillingness to cooperate and consult with each other among the teams

-

The teams undercut each other on prices in their fight for the same customer

-

There has been a lack of coordination, which has resulted in separate marketing promotions running at the same time and targeting the same customer categories, leading to a waste of corporate resources and time.

Robert decided to have a meeting with the Chinese marketing manager, Mr Zhang, and the team leaders, to discuss these issues. During the meeting, Robert communicated his thoughts about the teamwork situation and invited the attendees to comment in the hope that the issues could be solved at the meeting. Much to Robert's surprise however, John appeared to be the only one who was concerned about the situation. After the meeting, Robert had a private conversation with Mr Zhang, who said that the current situation was satisfactory and that the competition had increased the total sales of the company. Robert accepted it as a fact, but still expressed his opinion that Mr Zhang should improve the teams' coordination and cooperation.

A couple of months later, the Chinese partner, Mr Wang, had a discussion about John's sales performance. Mr Wang said that John had fallen behind all other marketing assistants and had not been able to get a contract for about two months. Wang then asked Robert if John should be relocated from his present position to the administrative department, where more people were needed as the business expanded. Robert was unhappy about Wang's suggestion and said that John had been a good member of staff, and unlike other Chinese staff had been straightforward in communication, positive in his effort to develop corporate business, independent in his judgement and willing to speak out with his opinions and suggestions. Robert wanted to keep John in his marketing position as an independent source of understanding of what was really happening at the frontline of the corporate business. As Wang held management control as a majority shareholder, he insisted that Robert relocate John. Robert also heard from an informal source that Zhang had claimed that he would eliminate John from the scene because John had talked too much about his department's problems. John was removed from his marketing position.

In this case, the points of differences are as follows :

Figure 4.2.1: a. Power distance has determined different approaches in communication of problems.

Figure 4.2.2: b. The varied degree of uncertainty avoidance led to attitudinal differences towards problems.

Figure 4.2.3: c. Collectivism-individualism predestined behavioural differences in response to problems

All these differences are attributed to a failure in effectively communicating the problems.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 648