7.11 The Public Store

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

Mailbox Stores hold purely personal information. By comparison, the Public Store is a shared repository whose content is available to anyone, subject to the access controls you impose on individual public folders or on folder trees (where subfolders inherit permissions from parent folders).

On the surface, public folders seem to add a lot of functionality to Exchange. It is good to have a place to hold shared information that you can make available to all users or selected groups of users who can access the folders using MAPI, IMAP4, or as Web clients (you can also direct NNTP feeds into public folders). It is even better that you can associate electronic forms with public folders to build applications, even if those forms are usually limited to MAPI clients, unless you take the time to develop a set to accommodate browsers.

The problem is figuring out how and when to use public folders in an Exchange deployment. When is it best to use public folders and where are network file shares more appropriate? Should I consider public folders to be a dead-end street and focus on deploying SharePoint Portal Server or a straightforward Web server instead? What training must I give to users to help them create and use public folders? What impact will public folder replication have on the network and what steps can I take to manage the traffic? For public folders, there are often more questions than answers.

7.11.1 The goals for public folders

To some degree, system designers and administrators do not know what to do with public folders and perhaps the fault is Microsoft's, because it has never been able to state just what public folders are good for. Before Microsoft launched Exchange in 1996, public folders seemed to offer an exciting platform for electronic forms and collaboration. You could take EFD, a Visual BASIC-like electronic forms designer program, and build all manner of forms to serve many purposes, such as travel requests, tracking expenses, reporting sales calls, and so on. You could set up public folders to be the base for online discussion forums, something that was in line with Microsoft's original name used during development, "public fora," or places where people can come together to share and exchange information, an electronic version of the original Roman Forum.

However, the result was not good. EFD was reasonably easy to work with, but it produced 16-bit code that ran slowly, especially when the folder contained more than a few items. In passing, it is worth noting that the old rule always to run demos with just enough data to get your message across holds true for public folders. You could not question Microsoft's earnest evangelism for public folders, but slow performance and the inability to support all platforms marked a quick end for EFD. Remember, in those days, Exchange supported a DOS client, so 16-bit was an important platform! The situation with electronic forms has certainly improved over the years and you can now generate sophisticated and powerful forms with Outlook. Folder performance is better too, but do not expect sparkling access to a folder that contains several thousand items, especially if the replica you use is not collocated on your mailbox server.

The other major use of public folders is as a replacement for network file shares, the logic being that it is much easier for users to navigate through public folders than a fragmented set of network shares. Public folders can successfully take the place of network shares, but only if you take care to create an appropriate folder hierarchy and maintain the folders, which is not always the case. It is not wise to use public folders to hold documents that change frequently, such as project updates, because of the replication load that this generates. Exchange performs public folder replication on an item level and does not support delta changes, so if you change a single word in a large PowerPoint presentation or a document, Exchange has to replicate the complete item, instead of just the changed data, to all of the servers that hold folder replicas. Public folders do make good repositories for static information such as policy and procedure information, since Exchange does not begin content replication unless someone changes an item in a folder.

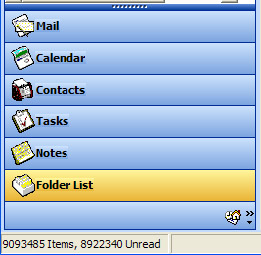

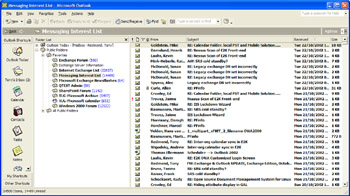

Few administrators rush to store more than a couple of hundred files in a network share, whereas they seem to be quite happy to accumulate many more items in a public folder, although maybe not quite as many as Outlook believes exist in Figure 7.28. Perhaps the number and size of files held in network shares is more obvious. Just like mailbox folders, public folders can hold thousands of items. For example, any public folder that acts as an archive for a busy email distribution list can quickly capture large numbers of items. Figure 7.29 shows one of the public folders used to capture contributions to an email distribution list at HP.

Figure 7.28: How many items can you hold in a public folder?

Figure 7.29: Viewing the contents of a large public folder.

Thankfully, public folder administration is easier today than ever before. Some of the early disaster areas such as the need for the infamous DS/IS Consistency Checker (which caused so many problems for Exchange 4.0 and 5.0 administrators), have been eliminated and replication normally flows smoothly. For instance, you do not have to guard against some other administrator rehoming all of the public folders from their original site into his or her site, or removing a complete set of folders from the hierarchy in a well-intentioned attempt to clean up things. As usual, everything depends on a solid design, so that is where we should begin.

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 188