1.2 MANAGEMENT OF VIRTUAL TEAMS

1.2 MANAGEMENT OF VIRTUAL TEAMS

The project manager of a co-located team is clearly the central control of the project as signaled by an array of physical status symbols visible to those who are in close proximity to the project manager. As such, he or she might become the principal project spokesperson to the project sponsor and to internal and external stakeholders who are in that location. Thus, in a traditional project, the project manager tends also to be the one, and the only one, who provides leadership for the project. However, in a virtual project, leadership is typically shared among team members based on the specific task at hand, location, and each team member's area of expertise. In a virtual team, the project manager may not be in the same geographic location as the sponsor or the customers. Therefore, liaison with the sponsor or customers might have to be performed by team members who share the same location and who are designated as relationship managers with key stakeholders. The duties of a virtual project manager, in comparison with duties of a collocated project manager, then would include a larger amount of facilitative and administrative functions.

The diverse membership of a global team can cause novel management problems, although it can also lead to greater innovation and ingenuity. During brainstorming sessions and other creative exercises, or even in day-to-day activities, more diverse and unorthodox concepts might be presented for evaluation and expansion. As a result, there is a diminished danger of what is known as groupthink , which is occasionally found in homogenized teams and which refers to situations where the team quickly reaches decisions without exploring several points of view.

An inescapable fact of a virtual project is that the project components are built, fabricated, and implemented in different locations. However, before the desired deliverable is submitted to the client, the individual components will have to be integrated. The tasks of unit testing and integration testing might become more complex for a virtual project than a traditional project. Therefore, in virtual projects, more so than traditional projects, detailed specifications must be developed at the onset of the project for each component of the deliverable . Equally important, a sophisticated configuration management system, again more so than one in use by traditional project teams, must be in effect for the project deliverables. One would hope that the additional effort necessary for component testing and integration will outweigh the efficiencies achieved by using a global virtual team.

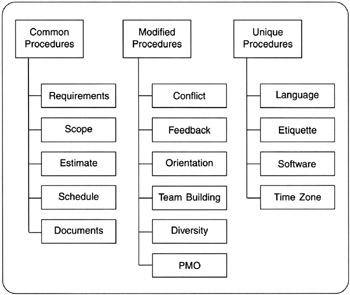

Teams that work on global projects require their own procedures and guidelines, although some of the procedures and guidelines can be adapted from the existing guidelines that have been prepared for traditional teams. The policies and procedures that deal with quantitative project performance can be used in virtual projects with minimal modifications. However, the procedures that deal with people issues will need to be modified extensively to make them applicable to virtual teams (Figure 1.6). One of the subtle missions of the environment-specific procedures is that a common team culture must be created. The premise is that even virtual teams need to deal with the cultural issues of project management, perhaps even more so. Project managers of global teams must deal with a new range of challenges, from language barriers and time differences to religious diversity to differences in eating habits. It cannot be overstated that subtle differences in the attributes of traditional teams and virtual teams can present complex challenges, if they are not properly handled in the early stages of team formation.

| |

|

|

| |

Figure 1.6: Virtual Team Procedures

Zeitoun (1998) reported the key challenges that were uncovered during a study of 40 project managers in several different industries. These challenges include differences in culture, laws, time, language, trust, and the use of technology. For example, in conducting asynchronous communication, one must be mindful of the time zones in which the team members reside. Team members must be made aware of the fact that, because of cultural differences, people will interact and behave in different ways. Language differences, which are very common in teams that span multiple countries , may lead to communication misunderstandings. Further, it may be harder to gain the trust and confidence of other team members in a circumstance where one never actually meets them in a physical setting. With customers and team members dispersed throughout the globe, team members must also become cognizant of the differing laws and regulations that may affect the project. Since virtual team members are more apt to place a heavy reliance on technology to achieve the goals and objectives of the project, a common suite of tools and appropriate training must be prescribed for the team members. Successful virtual teams are those that plan for all these special features in order to capitalize on the positive aspects of technical and intellectual diversity. Although traditional organizations shy away from virtual teams because they cannot easily guide them to success, enlightened organizations meet the special needs of virtual teams so that they might reap the efficiency benefits of them (Figure 1.7). To get a realistic picture of the trade-offs, an organization must weigh the financial advantages of virtual teams against the effort needed to meet the challenges of supporting these unique collections of project team members.

| |

-

Attractive Potential

-

Diversified in Many Respects

-

Culture

-

Geography

-

Language

-

Technology

-

-

Communication Challenges

-

Team-Building Challenges

| |

Figure 1.7: Global Teams

With appropriate measures in place, handling emerging issues or even conducting routine tasks might become somewhat easier in a virtual environment. However, traditional processes might have to be modified in order to make them specifically effective for multilocation members of virtual teams. The changes include blending the web into the document control procedures and contingencies for exchange rate volatility, which could change the project cost even if there are no other changes. Further, allowances must be made for time zones, cultural issues, and regional and political risks. Finally, project personnel must be sensitive to possible differences in terminology in different parts of the globe, even when using the same language.

Probably the most common transition mode for organizations, from traditional teams to virtual teams, is to attempt to apply the same policies and procedures in both types of teams. As project managers and team members realize that some of the procedures cannot be directly imported into the virtual environment, the policies and procedures will be modified with an eye toward the specific features of the team. Further, unique processes may have to be devised to handle the circumstances that occur only in virtual teams. Thus, the procedures and policies necessary for virtual teams fall into three separate categories: common procedures, modified procedures, and unique procedures (Figure 1.8). Common procedures are those that can be imported directly from the traditional team archives of best practices without any changes. These procedures deal with formats and templates for the project charter, requirements analysis, deliverable descriptions, and overall team performance indices, such as productivity, cost performance, and schedule performance. Other common procedures include those for project performance, quality management, contract management, and scope management. Modified procedures are those transportable procedures that have been used successfully for traditional teams, and creating their virtual team versions would require somewhat minor modifications and enhancements. The modifications can be minor, such as those necessary for the team charter, or they can be major, such as what would be necessary for conflict management and communication management. Other procedures that would be candidates for some level of modification include team building, team spirit, status reporting, negotiations, team maturity evaluations, and performance reward mechanisms. Unique procedures are those procedures and tools that must be developed exclusively for virtual teams to account for their special features. These procedures deal with issues of distance communication and the proper use of technology in handling the project's emerging issues, as well as complications that arise only in teams that are distant and virtual. They cover topics such as the proper use of e-mail, file transfer, and the recommended software for communication and for technical work. Unique procedures also deal with the use of portals for formulating project plans, for reporting best practices, for facilitating the integration of the final product, for brainstorming, and as a replacement for the traditional project war room. Other procedures that fall under this category are phone-conferencing protocols and videoconferencing processes.

Figure 1.8: Virtual Team Policies and Procedures

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 75