Section 23.6. Two Kinds of Music

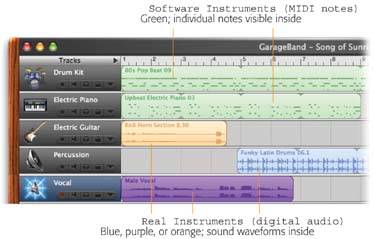

23.6. Two Kinds of MusicIf you've been reading along with half your brain on the book and half on the TV, turn off the TV for a minute. The following discussion may be one of the most important you'll encounter in your entire GarageBand experience. Understanding how GarageBand produces musicor, rather, the two ways it can create musicis critically important. It will save you hours of frustration and confusion, and make you sound really smart at user - group meetings. GarageBand is a sort of hybrid piece of music software. It can record and play back music in two different ways, which, once upon a time, required two different music-recording programs. They are: 23.6.1. Digital RecordingsGarageBand can record, edit, and play back digital audio sound from a microphone, for example, or sound files you've dragged in from your hard drive (such as AIFF files, MP3 files, unprotected AAC files, or WAV files). If you've spent much time on computers before, you've already worked with digital recordings. They're the error beeps on every Mac, the soundtrack in iMovie, and whatever sounds you record using programs like SimpleSound, Amadeus, and ProTools. The files on a standard music CD are also digital audio files, and so are the ones you can buy at iTunes.com. Digital recordings take up a lot of room on your hard drive: 10 MB per minute, to be exact (stereo, CD quality). Digital recordings are also more or less permanent. GarageBand offers a few rudimentary editing features: You can copy and paste digital audio, chop pieces out, or slide a recording around in time. In GarageBand 2, you can even transpose these recordings (make them play back at a different pitch) and change their tempo (make them play back faster or slower), within limits. But you can't delete a muffed note, clean up the rhythms , reassign the performance to a different instrument, and so on. Now then: To avoid terrifying novices with terminology like "digital recordings," Apple calls this kind of musical material Real Instruments . On the GarageBand screen, Real Instrument recordings show up in blue or purple blocks, filled with what look like sound waves (Figure 23-4).

23.6.2. MIDI RecordingsYou know what a text file is, right? It's a universal exchange format for typed text. In the early '80s, musicians could only look on longingly as their lyricists happily shot text files back and forth, word processor to word processor, operating system to operating system. Why, they wondered, couldn't there be a universal exchange format for music , so that Robin in Roanoke, with a Roland digital piano, could play back a song recorded by Susan on her DX-7 synthesizer in Salt Lake City? Soon enough, there was a way: the MIDI file . MIDI stands for "musical instrument digital interface," otherwise known as "the musical version of the text file." To turn your Mac into a little recording studio, a musician had to rack up three charges on the Visa bill:

Although Apple would go bald in horror at using such intimidating language, GarageBand is, in fact, a MIDI sequencer . It can record your keyboard performances ; display your performance as bars on a grid, piano-roll style; allow you to edit those notes and correct your mistakes; and then play the whole thing back. Behind the scenes, GarageBand memorizes each note you play as little more than a bunch of computer data. When it's playing back MIDI music, you might hear "Three Blind Mice," but your Mac is thinking like this:

From left to right, these four columns tell the software when the note is played, which note is played , how long it's held down, and how hard the key was struck. That's everything a computer needs to perfectly recreate your original performance. Musical information that's stored this way has some pretty huge advantages over digital recordings like AIFF files. For example, you can change the notes drag certain notes higher or lower, make them last longer or shorter, or delete the bad ones entirelywhenever you like. You can also transpose a MIDI performance (change its key, so it plays higher or lower) by an unlimited amount, with no deterioration of sound quality. You can even speed up or slow down the playback as freely as you like. When you make such an adjustment, the Mac just thinks to itself, "Add 3 to each pitch," or "Play this list of notes slower." The downside of MIDI recordings is, of course, that you can't capture sound with them. You can't represent singing , or rapping, or sound effects this way. A MIDI file is just a list of notes. It needs a synthesizer to give it a voicelike the synthesizer built into GarageBand. Apple refers to the sounds of GarageBand's built-in synthesizer as Software Instruments . They show up in GarageBand as green blocks, filled with horizontal bars representing the MIDI notes that will be triggered. Figure 23-4 makes this distinction clear. 23.6.3. Why It MattersWhy is it important to learn the difference between Real Instruments (sound recordings) and Software Instruments (MIDI data)? Because if you confuse the two, you can paint yourself into some very ugly corners. For example, suppose you "lay down" (record) the background music for a new song you've written. But when you try to sing the vocals, you discover that the key is way too high for you. If most of your accompaniment is constructed of MIDI (green) musical material, no big deal. You can transpose the entire band down into a more comfortable range. But if you'd recorded, say, a string quartet as part of the backup group, you may be out of luck. Those are Real Instruments (digital recordings), and you can't make radical changes to their pitch without some weird-sounding results. The bottom line: If you began your work by constructing a backup band out of green Software Instruments, you should generally finalize your song's key and tempo before you record live audio. Another common example: GarageBand lets you perform a neat trick with Software Instruments. After recording a part using, for example, a MIDI keyboard, you can reassign the whole thing to a different instrument whenever you like, freely fiddling with the orchestration. You can drag a blob of notes from, say, the Electric Piano track into the Country Guitar track. The Mac doesn't care which sound you use; its job is simply to trigger the notes for "Three Blind Mice" (or whatever). But although you can drag a blue or purple Real Instrument region into a different Real Instrument track, its instrument sound won't change (see Figure 23-5). In fact, you can never change the instrument sound of a Real Instrument.

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 314