Research Issues in the Management of Projects

|

Research is the practice of discovering information that was not previously available. Note that in this definition, it is a practice—a set of processes, techniques, and competencies—and that its product can be represented as information. Also, although the pun is unintended, it is best practiced rather than just occasionally attempted. The practices are better if performed frequently.

Research can be the collection of survey data, for example on markets, usage, performance, and so on. On the other hand, it can relate to building our conceptual and theoretical understanding.

Information can be defined as interpreted data. At a more subtle level, knowledge can be distinguished from information by the ability to predict through the application of theory (cognate models). At another level then, research is about interpreting data or information, and this requires a theoretical (conceptual) base.

The more challenging research is that which tries to build or extend our theoretical models. It is primarily with this kind of research that this chapter is concerned.

In some areas research is a very important and popular activity. In life sciences and new materials, for example, the current pace of research is feverish. The tide of knowledge is rolling back at a huge rate: lives and fortunes hang on research outcomes. Even in management, research answers can significantly affect companies' well being and performance. Management research is certainly alive and thriving. But what about research in project management? What kinds of issues are candidates for this kind of research in project management, and what in fact is being researched?

Project Management Research Areas

It is not the intent of this chapter to delve too deeply into suggesting such topics but a few might usefully be extended from Table 1. These are shown in Table 2.

|

Though specialized to the project management field, an important aspect of this list is that it is squarely about how project management can best contribute to improved business performance.

Research, surely, will be seen as more relevant when it is more evidently addressing business-driven issues such as these rather than being primarily middle management, tools, and techniques oriented.

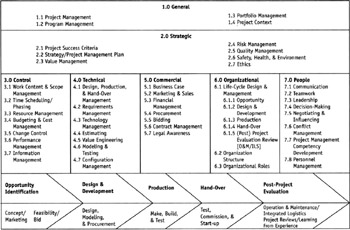

But is this fair? Is this a valid portrait of contemporary project management research? To test this thesis the Centre for Research in the Management of Projects (CRMP) recently reviewed all the papers and book reviews in PM Network and the Project Management Journal and in The International Journal of Project Management (IJPM) from 1990 to 1999.[1] Papers were classified against the Body of Knowledge (BoK) framework developed recently by CRMP that has now become the basis of the new Association for Project Management (APM) Body of Knowledge (and is likely to influence the revisions to the International Project Management Association [IPMA] Body of Knowledge when these are made in a year or two's time). The current CRMP BoK framework is shown in Table 3.

|

|

Before discussing the classification of project management research we should spend a moment considering the BoK model(s) and why they are so important in shaping our thinking on project management research.

The Body(s) of Knowledge and the Relevance to Project Management Research Paradigms

Between 1998 and 1999 the CRMP at UMIST conducted research sponsored by industry and APM to determine what topics project management professionals feel that project management practitioners should be knowledgeable in. A "straw man" framework was developed—admittedly based on the existing APM BoK but revised with some items omitted and some other topics added. Data was collected from over 117 companies. A very high degree of agreement was achieved on what topics companies believed project management practitioners ought to be knowledgeable in (Urli and Urli 2000). These topics are shown in Table 2.

It was the UMIST team's intent not so much to deliver a new BoK "model" but to determine genuinely (a) whether those polled considered it important that project management practitioners be knowledgeable in these areas or not and (b) what in fact is meant by these topics.[2] A structure for the new BoK only became necessary toward the end of the research when it became very apparent that reviewers wanted the topics grouped into a model containing a limited number of major elements (Morris, Wearne, and Patel 2000). The research team therefore developed a BoK model, a slightly revised version of which is shown in Table 3. (The initial version was published in April 1999.)

Why wasn't the Project Management Institute (PMI ) Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK ) structure used, and why is the CRMP BoK so much broader than PMI's?

APM's BoK was developed in the early '90s (1990–95), PMI's essentially between 1981 and 87 with a revision in 1996 and further refinement in 2000. APM's model was strongly influenced by research then being carried out into the issue of what it takes to deliver successful projects (Miller 1956). The question being asked was the "management of projects" one referred to earlier: "What factors have to be managed if a project is to be delivered successfully?" APM considered this to be crucial because it goes to the heart of what the professional ethos of project management is. Put simply, is it to deliver projects "on time, in budget, to scope", as the traditional view has had it (Morris and Hough 1987; Project Management Institute 1986; Pinto and Slevin 1987, 1988, 1989; Pinto and Prescott 1988), or is it to deliver projects successfully for the project customer/sponsor? In essence, it was felt it has to be the latter, because if it is not, project management is ultimately a self-referencing profession that in the long-term no one is going to get very excited about.

The APM BoK therefore incorporated knowledge on the management of topics that the work of researchers had identified as contributing to project success—such as technology, design, people issues, environmental matters, finance, marketing, the business case, and general management (Archibald 1997; Meredith and Mantel 1995)—in addition to the traditional PMBOK areas of scope, time, cost, human resources, quality, risk, procurement, and so on.

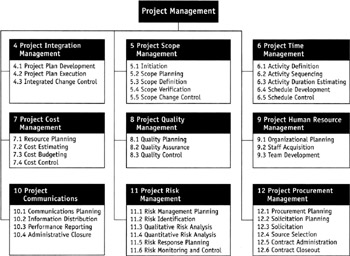

The resultant BoK is indisputably a broader model than PMI's. The PMBOK focuses on ten areas of project management, nine of which are "knowledge areas" (Figure 3) with another being general to project management. These ten areas overlap, but essentially are distinguished from "General Management Knowledge and Practice" and "Application Area Knowledge and Practice." General management is referred to as relating to management of the ongoing enterprise; recognized as "often essential for any project manager", it addresses leading, communicating, negotiating, problem solving, and influencing, together with a note on standards and regulations and culture. Application areas are described as categories of projects with common elements that may be significant in some projects but not in all. The paradigm is thus proposed that everything generic to project management is covered by the ten knowledge areas, with extensions where appropriate for general management and application areas.

Figure 3: PMI's Body of Knowledge Structure (PMBOK Guide – 2000 Edition)

The flaw in this model, I would suggest, is its failure to recognize and elaborate on the critically important responsibilities project managers have, and the generic functions they perform, in:

-

Ensuring that the project's requirements and objectives are clearly elaborated.

-

Defining the relation of the project to the sponsor's business objectives.

-

Developing the project's strategy.

-

Managing the evolution of the proposed technical solutions to the project requirements.

The key point is that, as research and practice have demonstrated (Lim and Mohamed 1998; Baker, Green, and Bean 1986; Baker, Murphy, and Fisher 1974; Cleland and King 1988; Cooper 1993; Morris and Hough 1987; Might and Fischer 1985; Pinto and Slevin 1989; General Accounting Office; National Audit Office; World Bank Operations Evaluation Department; http://www.standishgroup.com), there are generic practices and processes that all competent project management practitioners may have to call on and should be familiar with in these areas. Project management work in these areas is [very] often critical to project success, yet the PMBOK either totally or virtually ignores them. The result is that a huge swathe of the profession is led to ignore these dimensions; the discipline is downgraded from its real potential; and researchers are encouraged, tacitly, to overlook many of the issues that are most critical to the discipline's real effectiveness.[3]

The intent in making these points is not to argue that one BoK is "better" than another—hopefully the different models will slowly converge—but that as it stands the PMI model is unnecessarily, and even dangerously, delimiting the scope of the discipline. And one casualty of the paradigm it creates of project management is research in the subject. The broader CRMP model provides a better tool; it is proposed for mapping the range of research published in the Project Management Journal , PM Network , and IJPM and comparing this research with contemporary concerns in the management of projects.

[1]This makes the fourth such analysis. Martin Betts and Peter Lansley classified IJPM papers for the period 1982-92 (Betts and Lansley 1995). The topics they used to classify the papers (with the percent of papers over the period shown in parenthesis) were: human factors (15 percent), project organization (15 percent), project environment (12 percent), project planning (12 percent), conceptual models (10 percent), project information (9 percent), project performance (7 percent), risk management (7 percent), project startup (6 percent), project procurement (4 percent), and innovation (3 percent). Professor Stephen Wearne, at UMIST, has recently analyzed Project Management Journal and IJPM papers and PMI and IPMA conference papers using an early version of the CRMP BoK as the basis of classification (Themistocleous and Wearne 2000). Urli and Urli analyzed all the papers relative to project management in the bibliographic ABI-INFORM database from 1987 to 1996 using an "associated word" method (scientometric analysis) (Urli and Urli 2000). Their findings are interesting and relevant: the field appears to have broadened in scope during the review period while the themes seem to have become less and less linked—not surprising perhaps given the breadth of source material. Apropos the opening paragraph of this paper they reported, "Even though there is considerable professional interest in project management, one is forced to conclude that this interest is not as visible among university academicians, at least in North America" (Urli and Urli 2000).

[2]Apropos research: interestingly the APM review team, while welcoming whole-heartedly the empirical basis now provided by the CRMP data, was adamant that the APM version should not refer to abstruse, difficult-to-understand research papers, such as those published in IJPM!

[3]For example, the 2000 New Zealand Project Management Conference streamed all papers under the ten PMBOK topic areas. QED.

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 207

- ERP Systems Impact on Organizations

- Challenging the Unpredictable: Changeable Order Management Systems

- The Second Wave ERP Market: An Australian Viewpoint

- Intrinsic and Contextual Data Quality: The Effect of Media and Personal Involvement

- Development of Interactive Web Sites to Enhance Police/Community Relations