Findings

|

This section presents our key findings and discussion on the two research questions identified above. First, we explore the participant's understandings of project management and identify any gaps that may exist. Then we look at the process of selling project management and the interaction patterns between the buyer and seller.

Understandings of Project Management and Its Value

Initially, when we asked the participants to describe project management and brainstorm words around it, they described it as a linear type of activity, much like the definition provided in A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide) – 1996 Edition. "A project is a temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product or service" (Project Management Institute 1996, 167). "Project management is the application of knowledge, skills, tools, and techniques to project activities in order to meet or exceed stakeholder needs and expectations from a project" (Project Management Institute 1996, 167). These definitions are tactical in that they address tools, techniques, and skills. They also refer to a simple value statement of either meeting or exceeding expectations. The participants we interviewed described project management in tactical terms so it is understandable that as we asked them questions on selling project management, their approaches were tactical. None of the participants initially described project management as a philosophy and none referred to specific project management methodologies. In general, senior executives hold a fairly consistent, albeit basic, understanding of project management.

Although this initial definition gave the impression that project management principles were well understood in terms of the PMBOK Guide, further questioning revealed a diverse understanding of project management. Some participants viewed it as a tool or technique and others viewed it as a lifestyle, something that was ingrained in them they believed. Some described it as "part of their makeup" or an innate potential. It was described in religious terms on more than a few occasions and practitioners indicated they had "found the religion of project management" and described themselves as "converts." However, the majority of executives provided less passionate or detailed depictions. They tended to describe project management as either a very high conceptual issue or as a tactical toolbox for getting things done. The consultants were the only group that described project management in strategic terms such as "a core understanding or belief, scalable, flexible, and related to shareholder value."

Looking at the understandings of project management expressed by our participants in another way, we explored the tactical versus strategic understandings held by the buyers (senior executives, CEOs, CIOs) versus sellers (consultants, project manager practitioners) group. When project managers were asked to comment on the value of project management, their feedback reflected its importance and worth relative to projects, e.g., use a proven, structured methodology to show project results. One described it as an "insurance policy." Another described it as having the right people do the right thing at the right time. Many related the value to the project management priority triangle of "on time, cost, and scope."

The value of project management varied widely across our participant groups. To project managers, its value related to being more efficient and effective and helped them with their track records and career paths. As such, they focused on tactical strategies in selling project management (features, attributes) because these were the values of importance to them. To many in this category, the value of project management was so obvious it almost didn't bear explaining. The value of project management to large-scale consultants rested in increasing revenue through sales and establishing their presence on accounts. They preferred to focus on strategic level outcomes and to sell project management at that level; however, they were willing to focus on whatever benefits the client wanted to buy. Small-scale consultants were also interested in revenue but tended to sell project management benefits relative to their individual skills and expertise. The value of project management to executives related to being more efficient and effective in their business capacities and ultimately with their careers. They wanted to buy services that were aligned to their strategic business and personal goals. They were far more interested in buying tools or techniques that impacted strategic outcomes than those aimed at improving or sustaining innovative business operations.

In all the interviews conducted, only those at one projectized firm consistently described project management as providing strategic benefits; all others interviewed described it as a corporate tactic. The rationale given was that business priorities lay elsewhere. Consultants confirmed these views based on experience with the same clients.

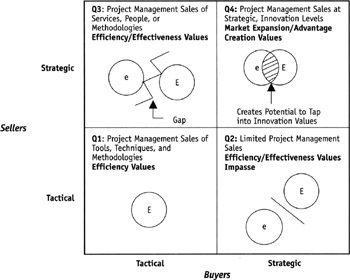

Summarizing these findings on the understanding and value of project management, we noted that the participants used efficiency and effectiveness values in different combinations that seemed to relate to their overall strategic or tactical understanding of project management. We depicted these relationships in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Project Management Understanding and Values Matrix

Figure 2 depicts the understandings and value of project management as viewed by the buyers and sellers. In quadrant 1 (Q1), project management is understood in tactical terms and purchased for efficiency values such as return on investment, reduced costs, and increased quality. Project management consists of tools and techniques. Most project management sales relationships in the past have predominated in this quadrant. Some may purchase project management in quadrant 2 (Q2) when buyers are strategic and sellers are tactical, but not many. Instead, the buyers will seek out sellers that are aligned to their values. In quadrant 3 (Q3) where buyers are tactical and sellers strategic, executives that purchase these project management services may come to realize the added value of doing so but possibly at the risk of staff resistance to change as project management is introduced at a more advanced level. Those selling strategically to tactical buyers and those selling tactically to strategic buyers (Q2, Q3) will soon find that they are not aligned and either adapt their sales strategies or be given even less access to senior management. Those selling strategic solutions will be aligned with buyers seeking effectiveness values (customer satisfaction, collaboration, organizational effectiveness, and knowledge sharing). This point may be viewed at the intersection of the quadrants. Quadrant 4 (Q4) is similar to Q1 in that there is alignment. The seller and buyer (Q4) understand the need to use project management for long-term success from an organizational and business standpoint. Buyers are seeking innovation values of market expansion (creating new markets, developing a global presence) and advantage creation (changing industry and market practices) (Frost 1999). Sellers are selling relationships at the business-to-business level. We observed that this advanced case existed at only one firm where we interviewed projectized staff.

Barriers to Selling Project Management

The feedback on barriers to successful project management experiences indicated that project managers and executives do not view project management as useful for more than a control mechanism. This limited view leads to the dismissal of project management as expensive overhead that has little connection to business value creation.

Some executives see project management as "easy and something anyone can do." Others cite resistance to purchasing project management as a lack of alignment between stakeholders as well as a lack of willingness to "put some skin on the table" and share in the project risk. Still others indicated that some executives lacked a clear understanding of project management, and that they viewed it as expensive overkill. One practitioner stated that, "These people don't know project management, they don't trust it, and they think it is make-work." The results showed that within the buyer's domain, there is a significant range of diverse opinions and attitudes toward project management.

Similarly, consultants believed that senior management did not understand project management or its true value potential. Some consultants indicated that executives did not understand what it takes to do projects well, nor did they appreciate the detail involved in project management. They saw the major barrier as a matter of changing mindsets and organizations at a cultural level. One interviewee noted that, "People have to feel the value to change, not see it."

Other examples of executive resistance to project management as cited by project managers included comments such as "Don't tell me how it's done, just show me the results." One key issue appears to be a mismatch between need and expectations. That is, project managers do not always use the right arguments to convince management that project management can address a particular management need. Thus, disconnects occur between the project managers who tactically sell the features and attributes (merits) of specific tools and techniques for project success to management. Instead, executives want results and benefits at the business level. Therefore, project managers need to convince executives of the value of project management by going well beyond the traditional metrics of delivering on time, on budget, and within scope. This will require project managers to first understand what they do to add value to business objectives before expecting executives to change the way they see things.

These barriers to selling project management were common themes in the course of extracting meaning from the interviews. The barriers reflect a resistance to change and a desire to maintain the status quo. The barriers at the executive level related to their understanding of project management and, frequently, their lack of experience with it to appreciate its merits. On the basis of the differing viewpoints, it becomes clearer why a difficulty exists in understanding the value of project management. In particular, the disconnect looms large when the intentions of the seller and buyer diverge significantly.

How is Project Management Successfully Sold?

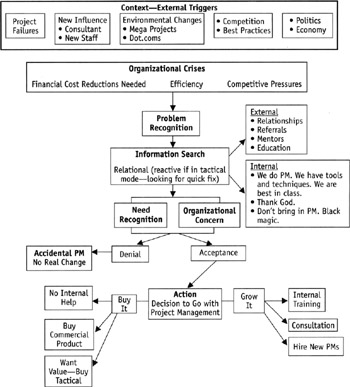

To answer this question, we asked each participant to tell us the story of a time when they were involved in the "purchase" or "sale" of project management within an organization. A synthesis of the stories resulted in the needs-based decision-making process depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Common Decision Process for Buying Project Management

Not one interviewee mentioned that project management was successfully sold proactively, as a strategic investment. Block (1991, 1992) supports the difficulty of proactively selling project management. In organizations not rife with crises, the executives seem disinterested in spending money on project management due to the perception that it is overhead and expensive. This explains some of the frustrations and challenges internal project managers faced in their efforts to sell project management proactively.

The interviewees indicated that the triggers to buy project management were related to a combination of external and internal factors as reactions to specific needs. Externally, the decision to buy project management was primarily related to competition and market share issues amplified by the following driving environmental forces facing today's organizations including: time compression, blurring of industrial and organizational boundaries, knowledge intensity, increasing returns to scale, and increasing information technology (IT) intensity (Saway et al. 1999). These external forces influence the value creation process and in turn, the very core of how a business functions. Internally (personally and organizationally), the decision to buy project management primarily relates to an extremely troubled or failing/failed project or the advent of mega/complex projects. The impact of these internal and external contexts left the companies feeling that they were in crisis situations.

Specifically, crisis situations forced executives to consider the merits of project management in terms of the business problem. Recognition that the firm needed to improve the project management processes was usually based on the "insurance policy" value of project management in reducing risk and buying them certainty or its contribution to their personal success. Senior management's willingness to pay (WTP) for project management is associated with their perception of the pay-off—total revenue must exceed total cost. They tend to avoid buying project management because the tangible benefits seem disconnected to the individual's WTP, especially on a larger project that takes a long time. Conversely, willingness to accept (WTA) the loss of project management as an option/strategy in the future becomes much more of a compensation issue that places the loss on a grander economic scale. For example, senior executives may be WTP for project management for $100,000 as an initial capital investment. However, the numbers may skyrocket when asked what they are willing to accept in terms of economic compensation for the loss of the opportunity to purchase this same opportunity in the future. In either case, the risk decision may rest on only one variable (typically cost), without reference to future opportunities over time, which acts to underestimate or overestimate the value of project management.

Decisions to buy project management are often triggered by "crisis situations." Thus, when executives begin searching for information externally, they reach out to specific project management consultants on the basis of prior relationships or referrals, e.g., those that were "top of mind" for specific services or skills. Rarely did the executives seek out new relationships with consultants or establish stronger ties with internal advocates of project management.

The results show three reasons internal sources of information are not cultivated. First, executives tended to view consultants with a different degree of credibility than their own project managers. In many cases the organizational crisis was in response to internal poor performance on projects. Project managers were usually the ones blamed or fingered when projects were in trouble and senior managers failed to appreciate the element of shared responsibility (Jugdev and Hartman 1998). This tended to reduce the credibility of project management proponents within the organization at the very time when executives might be ready to listen. Second, another challenge that internal project proponents faced in selling to their executives related to position power and language. Typically, project management proponents were not at a similar level in the hierarchy and so did not have access to resources, influence, or coalition and sometimes, more importantly, did not share a common language with the executives. When the project managers focused on project minutiae, executives further disconnected in terms of both receiving the message and listening. Finally, executives often received very mixed messages from their internal resources, messages often in direct conflict with those being offered by the consultants. Generally, senior executives got responses to queries about the state of project management in the organization that range as follows:

-

"We do project management and we do it well, so we don't need help." This reaction reflects a resistance to change and exemplifies denial in terms of project management improvements.

-

"We don't need project management. We have managed to do projects ‘the old way for years’ and do not need to change our practices or learn new ways." This reaction reflects a resistance to change as well as a lack of awareness of project management.

-

"We need help with project management. Thank goodness we are receiving help and our concerns are finally being heard." This level indicates a heightened level of awareness that improvements are possible.

Executives receiving the first two types of responses are likely to be either confused or angry where they have recognized the organizational problems and outcomes related to suboptimal project management practices. Executives receiving the third type of response are not likely to turn to this group for advice.

Those seeking to promote project management are severely handicapped by the tendency of executives to be triggered to explore project management only in crisis situations. Clearly, this group needs to develop better ways of gaining access and promoting interest in proactive project management in support of business objectives.

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 207