The Influence of Customers and Their Projects or Products

|

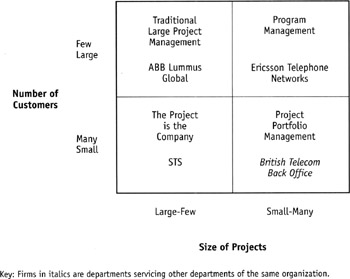

Different organizations adopt different approaches to the realization of this process dependent on the nature of their customers and the projects undertaken for them. Most organizations undertake a portfolio of projects for a range of customers, but we find that the operational processes adopted depend on whether the organization undertakes a few large projects or many small projects, and whether they have a few large customers or many small ones, see Figure 3. In reality most organizations operate in two or three quadrants from Figure 3. However, we find them adopting appropriate processes depending on the different quadrants. For instance, Reuters' back office operates in the bottom right quadrant for the delivery of new financial data products, but the top right for the delivery of data networks to distribute those data products over. Ericsson operates in the top right quadrant for the delivery of telephone networks to telephone operators, but bottom right for the delivery of telephone exchanges to organizations such as schools, hospitals, universities, and companies. Figure 3 also shows a typical firm from our sample in each quadrant. Names given to managers of each step in the operational management process by typical firms in each quadrant are given in Table 1.

Figure 3: Our Sample Size by Size of Project and Number of Customers

| Process | Big Projects–Few Customers | Big Projects–Many Customers | Small Projects–Few Customers | Small Project–Many Customers | Small Projects–Many Customers | Small Projects–Many Customers | Small Projects–Many Customers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Example | ABB Lummus Global | STS | Ericsson | Virtuell Fabrik (Katzy & Schuh) | BT Back Office | Reuters Product Development | Consultancy |

| Win Customers | Contract Management | Marketing Director | Account Manager | Broker | Account Manager | Marketing Manager | Director |

| Design Product &/or Process | Lead Engineers | Research Director | Solutions & Projects Managers | Network Coach | Solutions Manager | Product Manager | Managing Consultant |

| Make Components | Construction Supervisors | Suppliers | Project Managers | Factory Manager | Project Manager | Project Manager | Consultant |

| Configure Components | Project Engineers | Marketing Director | Solutions Manager | Project Manager | Project Manager | Project Manager | Consultant |

| Deliver Product | Project Director | Marketing Director | Account Manager | Project Manager | Solutions Manager | Product Manager | Managing Consultant |

| Maintain Customer Support | Contracts or Commercial Department | Marketing Director | Account Manager | Broker | Account Manager | Front-Line Business Unit Manager | Director |

Size of projects: We define a large project as one that is a significant proportion of the firm's turnover, and a small one that is a small proportion. Simple arithmetic says that if an organization is undertaking large projects it can only do a few of them, whereas if it is doing small projects it must be doing many of them to make up the turnover. The emphasis here is on the size of the projects as it is that dimension which determines the operational management approaches adopted.

Number of customers: Some organizations work for a few dominant customers, whereas others have a large number of customers. Again, simple arithmetic says that if there are a few customers, each must provide the firm with a significant proportion of its turnover (hence the reason they tend to be dominant). On the other hand, if there are many customers, each will provide the firm with a smaller proportion of its business, and the firm will be less reliant on any one customer. The emphasis here is on the number of customers as it is that dimension which determines the operational management approaches adopted.

Large Projects—Few Customers

Firms undertaking large projects for a few customers tend to be from the construction or heavy engineering industries. As the projects are large, dedicated teams are created to deliver them, and these are inevitably large, being almost small organizations in their own right. The project organizations adopted have what Frame (1995) describes as an isomorphic structure; the structure of the project organization reflects the nature of the task being done, with different team structures being adopted at each step of the operations process above.

Winning the order: This is the responsibility of the contracts or bid management department. The bid team is a task force, led by the bid or contracts manager. However, the structure of the task force may be one of two types described by Frame (1995), either a surgical team or an egoless team. In the surgical team the preparation of the bid is clearly managed by the bid or contracts manager, who draws on the expertise of others as required. In the egoless team, the group preparing the bid works together as a team of equal players, and the bid or contracts manager facilitates the process, perhaps even working as a junior member of the team. Most of the organizations in our study adopted the surgical team. In one company, ABB Lummus Global, bid management is viewed as a core competence and attempts are made to continuously identify and spread best practice in bid management.

Designing the product: At the design stage, a matrix approach is adopted (Frame 1995). That is, teams of engineers and designers work in their specialist functions, doing the design work for that function or discipline for all areas of the plant. A lead engineer will be responsible for the input of a given engineering discipline. They work closely with the project engineers who are responsible for coordinating the design of a given area of the plant and configuring the components of the product. This is matrix working at the project team level; it is not matrix management since the designers are working for one manager only, the lead engineer, and the project engineers must work through them to obtain the design input to their part of the plant.

Construct components of the product: The construction is managed by the project engineers and specialist construction supervisors. The team structure adopted is a task hierarchy (Frame 1995). Multidisciplinary teams do all the work to complete an area of the plant.

Configure the components of the product: The delivery of each area is managed by a project engineer, who ensures the plant is delivered in accordance with the design. They are responsible for link up and commissioning of the plant. During this stage, the team type moves from the task hierarchy adopted during construction, back to the surgical type as the final product is configured and commissioned for the customer. Multidisciplinary task forces work under the lead of a specialist to ensure work is completed quickly and efficiently.

Deliver the product to the customer: The project is managed by a project manager or, if of sufficient size and complexity, by a project director. Reflecting the importance of this role, one firm we interviewed assigned it, for a strategic project critical to the firm's future, to the director of the previous project; he went from a governance role on the board to an operational role. However, the new role was of such risk and significance to the firm's future and to the client that it was viewed as a development for the individual concerned. In all of the companies in our sample, project management is considered as a key source of value added both to the company and the client.

Maintain customer support: After commissioning, the project team will be disbanded. Ongoing customer support, which may included maintenance, the supply of spares, or the design of plant upgrades or new products, should be maintained. The maintenance of customer support is essential for the winning of new business. The work at this stage will be handed back to the functional organization to be undertaken by appropriate departments. However, it may be managed by a commercial or contracts department, on a matrix working basis again.

There are two further points of interest:

-

Organizations adopting this approach create a command and control structure for each project. Further, projects are often remote from the head office. Until recently, communications were such that project managers had to be empowered to make decisions without reference to the head office. Communications are now instantaneous, but project directors still expect to operate as the head of their autonomous command structure. We interviewed a project director from a company that had recently been taken over by a company from the defense electronics industry, which does many projects for a few customers (see discussion in a later section). More stable command structures are adopted by this type of firm, and our interviewee found it difficult working for a master that would not empower him to the extent he was used to. (He left and is now a general manager with a competitor, and his previous company is now in liquidation having been destroyed through the application of inappropriate governance structures for the business they were in.)

-

The overall project structure adopted is isomorphic, so as a project progresses the nature of the team varies, reflecting a changing need of the process and a changing emphasis on the customer and product. It starts as a surgical team of experts led by a specialist, focusing on the customers' requirements. For design, a matrix structure is adopted to manage the simultaneous input of several resources into several of components of the product. For construction, a task hierarchy is adopted to manage the input of the resources into the construction of discrete components. For commissioning, the focus changes back to the customer's requirements and so a surgical team is readopted. For ongoing support a matrix structure is adopted again, with specialists performing work on all areas of the plant as required.

In this scenario, there is a direct, one-to-one relationship between the project and the customer. We find in all the other scenarios a broker linking the project team to the customer is created in one form or another.

Large Projects—Many Customers

Only one organization from our sample could be said to be undertaking large projects for many customers. That is a research company, established to develop an idea of the entrepreneurial managing director. It really only has one project which is the entire business. Indeed, one of their customers is viewed as being the main potential user for this product once developed. However, there are many other potential users for whom different variants of the product will be made. Hence, although one is funding much of the development work, and obtaining patent rights as a result, they are seeking many other related (but different) applications for the product, and so are talking to several customers. However, as far as the internal project team is concerned, there is only one external customer, the marketing director. Hence the organization has created an artifice whereby the project team appears to be undertaking a large project for a single dominant customer. The marketing director is the broker between the project team and all the external customers. The firm also adopts an isomorphic approach for the project structure. Effectively at this moment the project team is only working on the design of the product, and different members of the team are developing different components of the product. The firm is considering setting up a manufacturing unit to make the product, which would just extend the isomorphic structure, but they are also considering contracting out the manufacture.

Small Projects—Few Customers

These organizations effectively undertake a program of work for each of the few clients. Each program is large in itself, so is a significant proportion of the firm's turnover, but each program is made up of several small projects. The difference with the scenario of the large project with few customers is that the large project leads to a single deliverable, and when the result is delivered the project is over. The programs undertaken here can carry on indefinitely, and the eventual out-come is always being updated. Each individual small project is well defined, but technology is continuously developing. Although the clients know the general scope of what they want, the actual scope evolves as the technology develops. One organization we interviewed from this category was Ericsson in the Netherlands. They are developing telecommunications networks for several of the operators in the Netherlands. The networks evolve with time, but there are clearly identifiable projects to deliver individual components of the network.

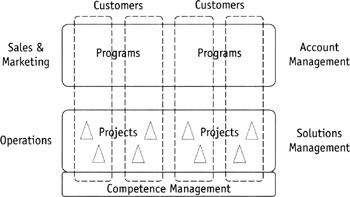

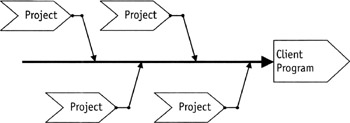

Because these organizations have a long-term relationship with their customers, they tend to adopt functional approaches to the management of the early and later steps of the process, see Figure 4. A sales and marketing division with account managers, manages the relationship with the clients and draws on the skills of an operations division to undertake the work. However, within the operations division are solutions managers who have a long-term relationship with the client, working with them on the evolution of the program. They identify with the client a need for individual components to be delivered, and only then are individual project managers assigned, from the operations division, to deliver the individual project. This leads to an overall structure of the program that has not been previously identified in the project management literature, which may be described as a fishbone approach, see Figure 5. The backbone represents the ongoing development of the program, with project teams consecutively contributing individual components. The individual project teams tend to adopt a specialist or surgical structure (Frame 1995). Thus the operations process works as follows:

Figure 4: The Relationship between Sales and Operations in a Project-Based Organization Undertaking Many Projects for Few Customers

Figure 5: The Fishbone Approach to Program Delivery in a Project-Based Organization Undertaking Many Projects for Few Customers

Win the order. This is a continuous (functional) process undertaken by accounts managers within the sales and marketing department. They win the order for the overall program and work with the client to maintain the relationship. The account managers and solutions managers are constantly working with the clients on the developments of the programs and the identification of new projects.

Design the product and deliver individual components: One surgical project team is responsible for design and delivery of each project. The project managers and their specialist teams design individual components of the program delivered by the projects. Each project delivers a single product, a component of the overall program. The project managers and their specialist surgical teams deliver the individual project components.

Configure the components: The solutions managers work with the project managers to configure the individual project components into the overall program. Though each component is in itself unique and novel, this does tend to be an ongoing, repetitive development task.

Deliver the product to the customer and maintain customer support: Hence the delivery of the final product to the customer and the ongoing support is also a repetitive development task, undertaken by the solutions managers and the account managers.

We see a different approach here for the adoption of command and control structures and team types than we did with the companies undertaking few projects for few customers:

-

Stable command and control structures, linked to the overall structure of the business are adopted in this scenario. This is possible because there is a long-term relationship with the client based on programs of development. Individual projects, though unique, novel, and transient, deliver only a small component of the overall product. Although the project managers may be empowered within the context of their project, their scope for flexibility is limited by the size of their project and the constraints imposed by the program. You can imagine the tension that arose when a firm used to this way of working applied their standard control techniques to the project director of a half a billion-dollar (US) project (see previous mention).

-

Again the team structure changes between the interface with the customer and the project delivery, the emphasis shifting from customer focus to product focus. In this scenario, the team approach adopted at the customer interface is a functional approach, sales and operations. The team structure adopted for projects is a surgical team, a team of specialists led by an expert, delivering a component of the product.

Small Projects—Many Customers

The most significant observation in this scenario is how organizations reduce the number of interfaces between project teams and their customers. The project teams here need to focus on completing the projects, managing the process, and delivering the product, not managing the relationship with a large number of customers. Just like in the one large project-many customers scenario, it is necessary to create an internal customer so that the project team can deal with that one customer. The project teams just do not have the capacity to manage an interface with a large number of external customers, and so an internal customer, or broker, must do it on their behalf. We have now given a transaction cost perspective of this governance structure (Turner and Keegan 2001). However, there are several ways of achieving this.

The Virtual Factory

The virtual factory was created by the University of St. Galen and involves a consortium of manufacturing companies around Lake Constance (Katzy and Schuh 1998). Bespoke products are delivered to clients which are beyond the capabilities of any one of the companies working on their own, either because they do not have the technical capability, or because they do not have the capacity. They deliver products to clients by forming a network in which individual companies fulfill different roles in the operational process. Effectively an isomorphic network is created project by project to meet the individual customer requirements for the product and process required to deliver it. This is most like the large projects-few customers scenario, with isomorphic project team structures created with bespoke command and control structures. Katzy and Schuh (1998) identify that companies in the consortium must undertake certain specialist roles on the project team, corresponding to some of the managerial roles associated with the operational process. These are listed in Table 1. Particularly, the broker acts as the customer interface, shielding the rest of the project team from the need to deal with several customers.

British Telecom's Back Office

British Telecom's (BT) back office suffers because the front office is constantly changing. Since 1990, the operating divisions have gone from three (domestic, business, and international) to sixteen and rising, recognizing growing telephone usage, market segmentation, and demographic changes. If the back office were to constantly adjust itself to deal with the changes in the front office, it would become chaotic. It has solved this problem by creating an internal market between itself and the front office. The internal market changes its structure to reflect the changing operating divisions. Effectively this works by the internal market maintaining a series of account managers, corresponding to the operating divisions in the front office, passing their requirements back to solutions managers, who place the orders for systems solutions on the back office. The arrangement is very similar to that illustrated in Figure 4. The individual projects so generated are of such a size and nature that the steps two to five in the operations process tend to be undertaken by specialist surgical teams.

Programs of Development

A variation of this approach used by many firms for their internal development work is to recognize that the projects can be grouped into development programs. A program manager is assigned to coordinate the projects, while a promoter or champion takes responsibility of dealing with the many internal customers who will use the development product and feeds their requirements into the project teams through the program manager.

Matrix Approach

This approach tends to be adopted by firms of consultants doing work for external customers. There are solutions managers working with customers and drawing on central resource pools to create teams of consultants to work for the clients. However, we interviewed one consultancy in the Netherlands that had grown so successfully that the application of this approach was leading to a growing feeling of isolation of the consultants from their resource leaders and from their clients. They solved the problem by changing their organization. They have created multi-disciplinary teams doing work for categories of clients. These strategic business units may service:

-

A dominant client

-

A geographic region

-

An industry

-

A collection of similar clients.

Effectively they have created several suborganizations, each a PBO. Some do large projects for large clients, some small projects for small clients. In this structure, the strategic business unit for which they work manages an individual's career development and work assignment. Their competence development is managed by the functional group to which they are assigned. The functional groups also develop new products for the strategic business units. So they too are PBOs servicing internal clients.

The Need for Different Approaches

The need to have different approaches for these different scenarios is recognized by some organizations and not by others. We interviewed one organization in the Netherlands from the engineering construction industry; an organization undertaking large projects for a few customers, with an American parent from the defense electronics industry, an organization undertaking many projects from one client. The American parent tried to manage the subsidiary in the close way required by their industry, rather than the empowering way required by the engineering construction industry, creating serious tensions.

On the other hand, this contrasts with ABB, an international company, with high project orientation. They recognize that not only do projects from the construction industry require an isomorphic structure to reflect the nature of the task, but also the culture of the different divisions needs to reflect the culturely different businesses they operate in and the customers within those businesses.

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 207