Establishing Change Control

Change control is an internal process an organization can use to block anyone , including management, from changing the deliverables of a project without proper justification. Change control requires the requestor to have an excellent reason to attempt a change, and then the proposed changes are evaluated in regard to their impact on all facets of the project.

The change control system (CCS) is a documented, formal process for proposing , reviewing, and allowing changes within a project. The CCS presents the process of how changes are reviewed for their value, costs, schedule impact, risks, and feasibility. The CCS also has a method to enter, track, and record the approval or denial of proposed changes.

In many organizations, the change control system includes a Change Control Board (CCB). This board completes the review and analysis of the proposed changes to determine their worthiness and justification. Your organization may call the Change Control Board an Engineering Review Board, Technical Review Board, or even the Technical Assessment Board.

There are dozens of reasons why management or the project customer may want to change a project s deliverables. The worst is when the recipient of the project deliverables drops by your office one day deep into the implementation plan and says, Hey, I forgot to mention that this project thingie you re working on also needs .

Another situation, equally painful, is a change that stems from your project team. In these instances, someone on your team will discover that the technology you are implementing really doesn t fit the bill. The technology won t actually deliver, the new technology will conflict with existing technology, or it becomes outdated during the course of installation. When this happens, you can almost hear your plan being sent through a paper shredder.

Or it could be your team is pulled in so many directions that it s impossible for them to keep the project on schedule. In organizations that are short on IT staffers , 60- to 80- hour workweeks are not uncommon. They ll be working on so many different implementations , development projects, and their daily duties to put out fires that it is physically impossible for them to keep pace with your project. In these situations, nothing short of additional resources will help.

As a general rule, it s easier to change the project deliverables in the beginning of the project than at the end. In other words, as the project moves closer to completion, the willingness to change the project deliverables wanes. The best method to avert serious change is prevention through serious planning. Again, like most aspects of project management, a solid preproduction of research, planning, and interviews with the users impacted by the project is crucial. You can avoid the preceding situations using these methods :

-

Interviewing the client (or end user ) of the product, in detail, as part of the initiation and planning phases, will ensure the requirements are well defined.

-

Researching and testing the technology thoroughly before the implementation phase. A testing lab or project simulation that emulates the working environment is a must in many IT projects.

-

Examining the required resources prior to the implementation. A reality check is needed to see if the existing staff has the time or knowledge to implement the proposed technology.

Impacts of Change

The one thing that always stays the same in project management is change. Sooner or later something will happen that will blindside your plan of attack and force you to change your plans.

A formal change to the project plan, regardless of who s responsible for the change, is serious business ”no matter how seemingly small or innocent it might seem. At this point of the project life, your Project Network Diagram (PND) is tight and solid. Recall that your PND is a visual representation of the flow of the work. It defines the paths to completion of the project and when tasks begin, and identifies the critical path. The critical path is the longest path of tasks within the PND. There should be little room for additional deliverables without expanding the project finish date ”not something that is always acceptable.

In addition, new deliverables cost money. A change in the project scope may mean additional resources ”internal or external ”and your budget may not be able to afford them. The changes can mean additional hardware and software expenses. Typically, additional funds will be required if the project scope is to change.

Team morale may plummet. Facing your team and telling them that all of the planning, research, and work so far is about to get additional criteria for completion is not good news. You ll need to handle the news with grace and tact.

Project Change Request

As you can imagine, you want to control and restrict changes to the project scope. When changes are inevitable, you need a formal process to incorporate these changes into the project plan. This formal process begins with something called the Project Change Request form .

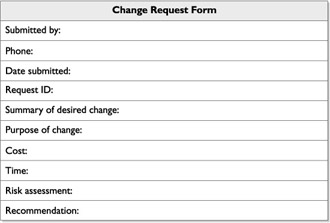

As you can see in Figure 9-1, the Project Change Request form formalizes requests from anyone to the project manager. The form can be electronic or paper based. The requestor, the project manager, and even the CCB will contribute to the form as they consider the change. The Project Change Request requires the requestor to not only describe the change, but also supply a reason why this change is appropriate and needed. Once the requestor has completed this form, the project manager, project sponsor, and other relevant stakeholders can determine if the change is indeed needed, should be rejected, or should be delayed until the completion of the current project.

Figure 9-1: The Project Change Request form formalizes proposed changes to a project.

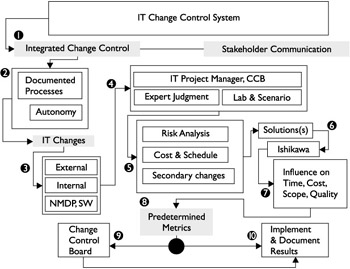

Change requests must follow a certain process to determine if they should be incorporated into the current plan. Figure 9-2 follows the path of the change request from start to conclusion. For example, a sample IT CCS goes through these steps (refer to Figure 9-2):

Figure 9-2: Change control must follow a predetermined path.

-

Integrated change control is a project-wide method of tracking change throughout all areas of the project. First, the project manager works with the stakeholders to determine if the proposed changes are really needed, funding changes within the project, and then managing them when they are inserted into the project.

-

Ideally, the organization has a documented, working CCS in place and the project manager has a certain amount of autonomy to approve or decline changes based on the nature of the submitted change request.

-

Next, the change request is filtered into one of several categories. This example focuses on three broad categories. External changes are changes from outside the project, such as service packs and technical advances. Internal changes are changes from the organization s stakeholders, project team, or (sigh) even the project manager. The last category of change presented deals with the hardware and software. (NMDP means network, memory, disk, and processor.)

-

The change request then moves to the project manager and possibly the CCB who rely on expert judgment regarding the proposed change. Expert judgment comes from those experienced with the technical nature of the change, such as subject matter experts, other project managers, and the project team. If needed, the change should be worked through in a lab or scenario environment to determine the actual impact on the project if it is approved.

-

The change request is then evaluated for risks, costs, schedule requirements, and any secondary changes the change may need if approved. A secondary change is simply the effect the change will have on other work within the project. For example, upgrading a workstation to a new operating system (OS) may consequently require upgrading older applications to work on the new OS as well.

-

The change solutions are evaluated. An Ishikawa diagram is one method of determining the cause and effect of the work, deliverables, and conditions within the change. An Ishikawa diagram is also called a cause-and-effect diagram or a fishbone diagram.

-

This step illustrates that the change, if it is to be approved, must be thoroughly evaluated ” especially with regard to its impact on time, cost, scope, and quality.

-

Predetermined metrics are values that would eliminate a change or allow it to continue in the CCS. For example, any change that affects the project budget by more than 10 percent is not allowed. Or any change that adds more than 14 days to the project is not allowed.

-

Should the change seem valuable , questionable, or prove to be worthy even though it does not necessarily meet the predefined metrics (such as providing a high return on investment), the results should be presented to the CCB for their approval or denial.

-

If the results of the change request are not worthy of moving to the CCB because of the predefined metrics, the change is automatically denied , and documented, and the requestor is informed of the status of his request.

Consider a project to release a new OS to hundreds of users based on a common image. One department, however, needs additional software installed that other departments do not. An OS image is an exact replica of an entire disk, generated using an imaging application like Ghost. Such applications allow an administrator to capture the entire image of a disk and then disperse it to multiple machines quickly and easily. Because the one department needs a slightly different image than the others, it s really outside of the predetermined project scope.

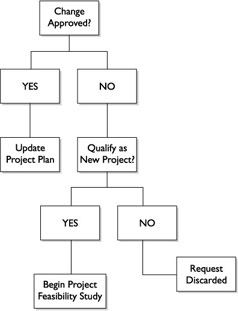

In this example, the department that needs additional software installed would basically require a different image of the disk to complete the job quickly and easily. While the request for the installation is valid, it does not fit within the current project scope. This request, as innocent as it sounds, may be better served as a separate project dependent on the completion of the current project. As Figure 9-3 demonstrates , project managers rejecting changes to a current project prevent runaway projects and advance change requests into the process to determine if a new project is warranted.

Figure 9-3: Change control can spur new projects.

If the research of the change does not prove that the change can or should happen, the change should be rejected. Reasons for rejection could be lack of time, technology, funds, or resources, or the complexity of the request qualifies it for a separate project.

Finally, if the change is approved for project incorporation, the project manager must begin a plan to incorporate the change into the project schedule. The project manager, the project sponsor, and the project team must address the incorporated change. An examination of the PND and a review of the resources and budget will be most helpful when determining where, when, and how the change will fit into the current project.

Change Impact Statement

A Change Impact Statement is a formal response to the Project Change Request form. It summarizes the proposed actions to incorporate the changes. Usually this is a listing of the paths and trade-offs the project manager is willing to implement. In some instances, the Change Impact Statement is given back to the customer with several responses the requestor can choose from. There are seven different responses a project manager can use on the Change Impact Statement:

-

The proposed change is not approved. Sorry! The change cannot be incorporated into the project scope. These add-on wishes cause runaway projects, scope creeps, and a waste of funds, time, and resources.

-

The proposed change can happen within the current timeline, with the current resources. Good news! The change is simple and won t require additional resources or time. This can be something as simple as changing the name of a domain, server, or another variable.

-

The proposed change can happen with the current resources, but will require an extended timeline. The change request will take additional time to finish the project, but the current resources are able to complete the additional activities.

-

The proposed change can happen within the current timeline, but additional resources are required. Based on the change and the project, the deadline may not be movable. Therefore, in order to complete the change on time, additional resources will be needed to incorporate the additional work.

-

The proposed change can be completed, but the timeline will need to be extended and additional resources are required. Phew! Based on the change request, the timeline is no longer realistic nor is it achievable for the current project team to complete the change. This stems from adding an additional component that requires skills beyond those of the current project team.

-

The proposed change can be completed, but the deliverables will be produced in a tiered strategy. This reaction to the change accepts the proposal, but the deliverables will be released in priority sequence according to the customer. For example, if an OS rollout was to be just for a few departments, but the rest of the company was added to the plan, this solution could address the change. Management could choose the department order in which the OS rollout would occur.

-

The proposed change cannot occur without considerable changes to the project plan. Bad news! The proposed change to the project is so significant it would render the current plan obsolete. The changes must have an excellent justification for scrapping all of the hard work, time, and funds committed to the project to date. An example could be a shift in business cycles, a company buyout, a new technology, or change in management.

Internal Project Trouble

The most difficult changes to the project plan, unfortunately , happen from within. These changes are not always changes brought about by discovery of a new technology, a flaw in the project plan, or a conflict with the implementation. These changes are brought about by the one variable in any project that remains constant: the human element.

The human element is the predictable problem that arises from team members who fail to complete their assignments, fail to communicate troubles or flaws, or lose interest in their work. These blunders are the epitome of leadership failure. You, the project manager, must have such an active role in the implementation phase that you can sense trouble brewing like a fireman can smell smoke. You need to spring into action, address the issue at its conception , and squelch it before it erupts into a full-fledged delay!

On long- term projects, it is easy for everyone, including the project manager, to get burned out on the implementation. As Figure 9-4 shows, the longer a project, the easier it is for the project team and the project manager to lose interest and focus. Once a team member gets burned out on a project, he loses interest, care, and motivation. It s difficult to spark a team member s drive once he s reached this point. A project manager should sense a team member s dedication waning long before it actually happens.

Figure 9-4: Long-term projects require dedication to avoid burnout.

Another problem IT project managers are often faced with is turnover . As you may know, within the IT industry, professionals are constantly climbing their own ladder of personal achievement. Workers come and go as they shift from company to company, and move up within their own organizations.

When a team member leaves the team because she resigns from the company (or moves within the company), you must act immediately to find a replacement. This is no easy task. If you re lucky, someone within the organization can join the project team and begin where the original team member left off.

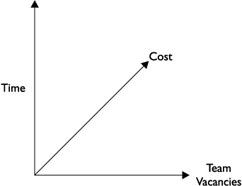

As Figure 9-5 depicts, the longer a project team position is vacant during the implementation phase, the longer the project s delay. In addition, costs may rise on the overall project as hours increase and IT consultants /contractors may be brought in to fulfill the duties of the missing team member.

Figure 9-5: Vacant team member positions cause delays.

What s likely is that a new team member will join the team, and you ll be faced with assessing that person s skills and then rearranging the resources to complete the project on schedule. For example, if you re involved with an application development team and your SQL guru leaves the company, you may not have to hire a new SQL pro. Instead, you may have to move one team member who knows SQL into the role of the SQL pro, and promote a new team member into the now vacant app developer role ” assuming that the person s skill sets match your requirements.

You may also have no other choice but to hire an independent contractor, a consultant, or an integrator to help the team finish the project. This independent contractor will most likely cost more than the hourly wage and benefit costs of the team member who has left the company. Additional funds may be required to complete the project.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 195