The Solution: Tell the Rest of the Story

Since the problem of coming up with ugly stories and suffering the consequences takes place within the confines of your own mind, that s where the solution lies as well. Effective problem solvers observe an infraction and then tell themselves a more complete and accurate story. Instead of asking, What s the matter with that person? they ask, Why would a reasonable, rational, and decent person do that?

By asking this humanizing question, individuals who routinely master crucial confrontations adopt a situational as well as a dispositional view of people. Instead of arguing that others are misbehaving only because of personal characteristics, influence masters look to the environment and ask, What other sources of influence are acting on this person? What s causing this person to do that? Since this person is rational but appears to be acting either irrationally or irresponsibly, what am I missing?

You can answer these questions only by developing a more complete view of humans and the circumstances that surround them than the traditional What s wrong with them? And if you do amplify your situational view, not only will you gain a deeper understanding of why people do what they do, you ll eventually develop a diverse set of tools for orchestrating change.

Consider Six Sources of Influence

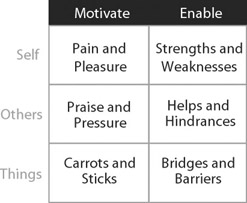

To help expand our view of human behavior, we ve organized the potential root causes of all behavior (including failed promises), into a model that contains six cells . At the top of our model are two components of behavior selection. In order to take the required action, the person must be willing and able. Each of these components is affected by three sources of influence: self, others, and things.

Cell 1: Self, Motivate ( Pleasure or Pain)

We already know the first cell. It s the one that, considered alone, makes up the fundamental attribution error. People base their actions on their individual motivation or disposition. Does the action motivate? Does the person enjoy the action independent of how others think or feel? Does it bring pleasure or pain? That s the model we already have in our heads, and it s partially true. People do have motives. Human beings do take pleasure in certain activities, and it could even be true that they enjoy making us suffer. However, this model is also the source of influence that gets us in trouble when it s the only factor we consider.

Cell 2: Self, Enable (Strength or Weakness)

We can double this simple model by adding individual ability. We now have two diagnostic questions: Are others motivated to do what they promised ? and Are they enabled ? (Does the action play to a person s strength or weakness? Does he or she have the skills to do what s required?) By expanding the model from one to two cells, we acknowledge the fact that people not only must want to do what s required, they also need the mental and physical capacity to do it. For instance, maybe your company s customer-service agents aren t returning calls to hostile clients because they don t know how to defuse the hostility . Perhaps nurses aren t using protective gloves consistently because they can t put them on quickly enough.

With two options to choose from, we also have another story to tell ourselves . Rather than judging others who violate an expectation as unmotivated and therefore selfish and insensitive, we add the possibility that maybe they actually tried to live up to their promises but ran into a barrier .

| |

Admitting that a problem might stem from several different causes, changes our whole approach. We aren t certain, we aren t smug, we aren t angry , and we slow down. We re curious instead of boiling mad. We feel the need to gather more data rather than charge in guns-a-blazin . We move from judge, jury, and executioner to curious participant.

| |

Others

None of us works or lives in a vacuum . We make a promise, and more often than not we sincerely want to deliver on it. We may even have the talent to do so. But what happens when others enter the scene? Will coworkers, friends , and family members motivate us? Will they enable us? Social forces play such an important role in every aspect of our lives that any reasonable model of influence must include them.

Cell 3: Others, Motivate (Praise or Pressure)

From the way adults talk, you d think peer pressure disappears a few weeks after the senior prom. We constantly warn our children against the insidious forces wielded by their friends. Yet rarely do we consider the fact that those forces aren t switched off in some mystical ritual when we finish high school. Adult peer pressure may be less obvious than its teenage counterpart , but it s no less forceful.

For instance, what do you think will happen if the supervisor of the software testers walks up to one of them and says, Hey, Chris, we re running behind schedule. Could you hurry things along?

What do you mean? Chris asks.

You know, maybe finesse the final tests. The software seems to be running smoothly.

And with that simple request the tests are dropped.

Is the other person being influenced by peers, the boss, customers, family, or for that matter, by any other human being? Remember the work of Solomon Asche and Stanley Milgram? They created conditions in which social pressure drove people to change their opinions , lie, and even inflict pain on others. Should it surprise us that most of the ridiculous things both children and adults do are a result of simply wanting to be accepted? Health-care professionals violate standards, scientists turn a blind eye to safety, accountants watch their peers break the law, and nobody says anything. Why? Because the presence of others who say nothing causes them to doubt their own beliefs and their desire to be accepted taints their overall judgment. Peer pressure is the mother of all stupidity.

Cell 4: Others, Enable (Help or Hindrance)

In addition to motivating you to do things, other people can enable or disable you. They re either a help or a hindrance. For you to complete your job, your coworkers have to provide you with help, information, tools, materials, and sometimes even permission. Unless you re working in a vacuum, if your coworkers don t do their part, you re dead in the water.

For example, what about the software engineers ? What if their testing package failed? What if the person responsible for keeping the server online went off to a technical seminar and didn t keep them up and running as long as needed? Who knows? Maybe that s why the software is giving final assembly fits. That is the whole point of this discussion. Who knows ? We re going to have to gather data.

You re a Big Part of the Social Formula

Let s add one more piece to the social formula: you. You re a person too. You may be acting in ways that are contributing to the problem that is bothering you. You ve got the eyeballs problem: You re on the wrong side of them if you want to notice the role you re playing. For example, a staff support person misses a deadline because she didn t like the way you made your initial request. She thought that when you rushed up to her, project in hand, the way you pushed for a commitment was too forceful, demanding, and insensitive to her needs. She didn t say anything, but she did find a way to put your request at the bottom of her priority list: Sorry, I just never got around to it.

We encounter the same problem at home. You re at your wits end because your husband is punishing and cold to your children (his stepchildren). You wonder why. Is he just selfish and impatient? Could it also be that you rarely show sympathy for his frustrations with them? Perhaps you are making him feel isolated and resentful about the challenges he faces, and that helps him feel more justified in behaving rudely to your children.

But that s not all. As a big part of others social influence you can also affect their ability to meet your expectations. How about that time your son didn t complete his science project on time? You forgot to buy the ingredients for the volcano he was building on the way home from work. When that happened , of course, you realized that you were part of the problem. When you don t enable people, you re likely to notice your role and others are certainly likely to say something to you if you let them down.

When your style or demeanor or methods cause resistance, others may purposefully clam up and not deliver, and you won t even know that you re the cause of the problem. You ll just hear a lot of excuses and get no honest feedback, particularly if you re in a position of authority. In this case, you need to turn your eyeballs inward and look for the whole story by asking yourself, What, if anything, am I pretending not to notice about my role in the problem?

You know people out there who do things that cause others to push back, resent them, reject their input, or drag their feet. Here s a news flash: Sometimes you may be that person.

Things

As you watch people going about their daily activities, you see that a great deal of what they do is affected by the things around them. This isn t always obvious to the untrained eye. In fact, many of us are fairly insensitive to our own surroundings, let alone the surroundings of others.

For example, you re trying to lose weight and don t realize that the cash or credit cards you re carrying enable you to set aside the lunch you packed and buy a high- calorie restaurant meal. You re hungry (individual, motivate), your friends ask you to lunch (others, motivate), and the credit card you re carrying (things, enable) puts you over the top. You also don t see the distance to the fridge as a factor or the fact that you fill it with unhealthy foods as a force. Of course, all are having an impact.

Human beings don t intuitively turn to the environment, organizational forces, institutional factors, and other things when they look at what s causing behavior. We often miss the impact that equipment, materials, work layout, or temperature is having on behavior. We ve also been known to miss the way goals, roles, rules, information, technology, and other things motivate and enable.

Cell 5: Things, Motivate (Carrot or Stick)

How do things motivate us? That s simple enough. Money motivates people; that we know. Guess what happens when money is aimed at the wrong targets? For instance, managers are rewarded for keeping costs down, and hourly employees are rewarded for working overtime. They re constantly arguing. Quality specialists earn bonuses for checking material, and production employees for shipping it. They too seem to have trouble getting along. Maybe a team-building exercise will reduce the tension. Perhaps conflict-resolution training will help. Yeah, right.

When they explore underlying causes, experienced leaders quickly turn to the formal reward system and look at the impact money, promotions, job assignments, benefits, bonuses, and all the other organizational rewards are having on behavior. It is sheer folly to reward A while hoping for B. Savvy leaders and effective parents get this.

Here s how this concept applies to a community example. One of the greatest challenges in influencing at-risk youth in inner-city areas is that the models of successful careers that they see often involve the sale of illegal drugs. It isn t just the influence of others that lures them into illicit trade; it s financial . Until they see clear alternative pathways to financial well-being, thousands of young men and women will be lost to this social cancer.

Frustrated couples are no less strongly affected by this powerful source of influence. The foundations of thousands of marriages continue to erode as one or both spouses give their hearts to careers that promise increased status or rich rewards to those who pay the price.

Cell 6: Things, Enable (Bridge or Barrier)

When it comes to ability, things can often provide either a bridge or a barrier. For example, imagine you re trying to get the people in marketing to meet more regularly with the people in production. They currently avoid each other like the plague because they don t get along. You ve aligned their goals and rewards, but marketers still call production folks thugs and production specialists call marketers slicks. You believe that if you can get them in the same room once in a while, many of their problems will go away. But how? What will it take to get them to meet more often and eventually collaborate?

First you write an inspiring memo. Nothing happens. Then you add interdepartmental collaboration to the company s performance-review form. Nada. Next comes a speech, then veiled threats, and finally you create an award program that honors the Collaborator of the Month. You tell the various division heads to nominate an employee for the award, and they argue endlessly about who should win.

Now you decide to do some out-of-the-box thinking, only this time it s out-of-the-cashbox thinking. The heck with rewards; it s time to turn to other things. Could you do something to the physical aspects of the organization that would allow people to interact more easily and more often?

Yes, you could. In fact, if you want to get the two groups to meet more often, think proximity. When it comes to the frequency of human interaction, proximity (the distance between people) is the single best predictor . Individuals who are located close to one another bump into each other and talk.

When it comes to work, people who share a break room or resource pool tend to bump into each other as well. Move the marketing offices closer to the work floor, throw in a common area, and the two warring groups may warm to each other. Proximity or the lack thereof has an invisible but powerful effect on behavior.

The following are a few other things that can affect ability.

Gadgets

Gadgets can have a more profound impact on social structure than people imagine. For example:

-

Cooks and waitresses used to fight tooth and nail over what had been ordered and whose orders got filled first until a researcher invented the metal wheel that controls and organizes orders. With the advent of the wheel, waitresses stopped shouting commands at cooks and cooks stopped getting angry and fouling up the orders.

-

A mother was constantly punishing her son for not coming home before dark. The boy didn t know when before dark was, would wait until it was actually dark, and got in trouble ”until his neighbor gave him a watch and his mother gave him a specific time to be home.

-

A father turned the hot water off at the source so that his wife and daughters wouldn t take so long in the shower. They resented his actions. One day Mom put an egg timer in the shower, and the problem went away.

-

One family determined that its microwave had put distance between the parents and their children. Was this a lame excuse ? Not when one realizes that their first microwave eliminated the one time the whole family came together: the evening meal. With their fancy new zapper, the children were able to make what they wanted when they wanted. Without realizing it, the family members lost a key force and began to pull in separate directions.

The point is not that gadgets are bad but that they can have a more significant impact than people might imagine.

Data

A financial services company couldn t get people to help cut costs until it published both cost data and financial records. With the same goal in mind, factories now prominently display the cost of each part. In a large inter-city hospital the health-care professionals regularly chose to use rubber gloves ($30 a pair) instead of less comfortable latex gloves ($3 a pair), even for short procedures. After endless memos encouraging people to save money, administrators posted the cost of the gloves in prominent locations, and glove expenses dropped overnight.

One wise parent tired of the endless requests of his teen for everything from designer tennis shoes to a designer sports car. One evening it struck him that an ounce of information might be worth a pound of crucial confrontations. He openly shared everything about the family finances. Eventually his daughter ”and we re not making this up ”asked if she should get a night job to help out.

Completing the Story

When you encounter people who aren t doing what they re supposed to be doing, it s easy to wonder: What the heck were they thinking? Left to our natural proclivities, we tell a simple yet ugly story that casts others as selfish or thoughtless. We mature a little bit every time we expand the story to include a person s ability. Maybe others don t know how to do what they ve promised to do. We also cut off our anger at its source. Not knowing for certain what s happening, we have to replace anger with curiosity . This puts us in a far better position to discuss an infraction as a scientist, not a vigilante.

Throw in the influence of others and the story starts to reflect the complexity of what s really going on. The fact that social forces are likely to be a huge part of any infraction doesn t escape a savvy problem solver. Only a fool purposely pits people against their desire to belong, feel respected, and be included with their friends and colleagues. Understanding the influence of others is a prerequisite to effective problem solving.

Finally, if we really want to step into the ranks of those who master crucial confrontations, we need to consider the physical factors, or things , surrounding a failed promise. This isn t intuitive. In fact, rare is the parent or leader who looks at either the reward structure or other environmental factors when trying to bring to the surface the root cause of a behavior. Learn how to do this and you ll be in a class of your own.

Use the Six Sources of Influence

Combined, these six distinct and powerful sources make up The Six-Cell Model, a diagnostic and influence tool that was illustrated earlier in this chapter.

How About Our Software-Testing Friends?

What actually caused the software problem during final assembly? Several of the forces contained in our model played a role:

-

A supervisor had been sent to the scene, where she learned that the programmers were unfamiliar with the latest version of the testing software (individual ability).

-

The supervisor had offered to obtain a tutorial, but the material was across town at headquarters (organizational ability). The team leader said he d get it, but didn t (social ability).

-

The team leader never got the material because he was stopped in the hallway, where he was told to prepare for a walk-by from a big boss from headquarters (social motive).

Did the code writers skip the testing because they didn t like doing it? That could have been the case, but it wasn t. Consequently, if the managers had punished the operators for not being motivated, it wouldn t have remedied any of the underlying causes and most certainly would have caused resentment.

One Final Comment

The best leaders and parents aren t lax with accountability, nor do they let themselves stew in a stupor of self-loathing. If the other person does turn out to be at fault, those who are masters of crucial confrontations step up to and handle the failed promise. In fact, we ll explore how to do exactly that in later chapters.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 115