Chapter 6: Detect the Meaning of Life s Moments

Live as if you were living already for the second time and as if you had acted the first time as wrongly as you are about to act now! [ 1]

Michelle had recently celebrated her fiftieth birthday but was not quite ready to admit that she had reached the half-century mark and was dreading retirement age. In fact, she was not a happy camper and not inclined to celebrate anything in her life. Twice divorced and the single mother of two Generation X ers, Michelle s personal life, as far as she was concerned , left much to be desired, and she didn t feel much better about her work life either. Since her last marriage ended, she had been having a very difficult time holding any kind of steady employment. Whenever she did find a job that seemed worthwhile, it always soured quickly. Over and over, Michelle would find herself stressed out at work; always, of course, for some reason that had nothing to do with herself ”a poor boss, lazy co-workers , unclear job description, lack of support, and so on. Consequently, she was never satisfied with her present work situation and certainly never imagined that she could have a meaningful career path .

Because she was also stressed out at home, Michelle was experiencing a double whammy with no end in sight. She seemed consumed by a need to put out fires at work and at home, with nothing in reserve for determining the root causes of her anguish. As she became increasingly depressed over her life situation, Michelle s tendency to externalize the reasons for her plight hardened into a suit of impenetrable armor . Over time, Michelle became oblivious to her own role and responsibility ”as co-creator of her miserable reality ”and effectively lost touch with the meaning of life s precious moments because she was too busy complaining about what life had been doing to her. In her mind, life had dealt her a bad hand, so at this stage of her existence there was nothing to do but bear the suffering and complain loud enough so that everyone around her ”her family, friends , coworkers, and the like ”would hear her cries of pain.

The meaning of it all is that there is no meaning, said the golfer Walter Hogan in the movie The Legend of Bagger Vance. Michelle would agree, for the search for meaning had no value to her. Her life was meaningless and most likely would continue to be meaningless ”unless perhaps some sort of miracle came her way ”for she wasn t inclined to search for anything different. Perhaps Michelle was simply experiencing a mid-life crisis, you ask? Perhaps. Whatever the reason, ironically Michelle had chosen to take an early retirement from life by giving up on her search for meaning.

We don t create meaning; we find it. And we can t find it if we don t look for it. Meaning comes to us in all shapes and sizes. Sometimes it looms big in our lives; sometimes it slips in almost unobserved. Sometimes we miss a meaningful moment entirely until days, months, or even years go by and then suddenly something that once seemed insignificant becomes a pivotal, life-changing moment. Sometimes, too, it is the collective meaning of many moments that finally catches our mind s eye; as if we weave together a living quilt from patches of moments that, by themselves , would have passed us by unnoticed. And, although we are not always aware of it, meaning, Frankl would say, is in every present moment. It goes without saying ”wherever we go. All we have to do, in daily life and at work, is to wake up to meaning and take notice.

The true meaning of life is to be discovered in the world rather than within man or his own psyche, as if it were a closed system. [ 2 ]

It sounds easy but these days it can feel almost impossible to do. Our sound-bite society speeds up reality to such an extent that stopping to smell the roses seems archaic, like some sentimental activity from an earlier era. In an era of fast companies, it is like we have forgotten how to slow down and how to reflect. We re more likely to stop and use our cell phone, or check our email. Time is getting away from us, and so is meaning. And, like time, we notice meaning when there isn t much left. We wake up one day, or don t sleep one night, and suddenly our exhaustion, the fragmentation of our lives, the unrelenting pace of things, leaves us bereft of meaning. What is it all about, we wonder ?

There is no answer to the big question unless we discover answers to the smaller ones: What are we doing? Why are we doing it? What do our lives mean to us? What does our work mean? Every day our lives are rich with meaningful answers. But only when we stop long enough to appreciate it will meaning bloom in our lives. We have to really be there to detect and know meaning, and most of the time we are on our way somewhere else. The frenzy of activity in our lives ”at work and at home ”is challenging the very nature of our existence. And if we don t stop long enough to sniff out our own existence, we turn meaning into an impossible dream.

So before we go on the hunt for meaning at work, we have to know that meaning means something. Our lives are full of it. The rhythm of existence ”the tides, the stars, the seasons, the ebb and flow of life, the miraculous being-ness of it all ”is always available to us at every given moment. There are no exceptions. Every astronaut who ever returned from outer space attests to the great miracle that is life on this earth. All of science conspires to get men and women into space, but it is when they return to earth that the miracle really begins. They see the planet suspended in the vastness of space, its continents and clouds luminous in an unfathomable universe, all life hanging by some invisible thread of possibility. Their jobs take them to cosmic heights of achievement, yet it is being back on earth that brings them to their knees.

The thirteenth-century Sufi poet Rumi writes , It s never too late to bend and kiss the earth. The meaningfulness of life, as we know it and don t know it, is manifest everywhere on this fragile planet. Wherever we are and whatever we do, it is this very existence of life that calls us to meaning. How are we inviting life into our lives? How are we bending and kissing this earthly experience? How are we acknowledging meaning in our lives, through our work, at our jobs? The answers are as varied as our needs.

The distinction between what has professional credibility and what doesn t is insidious. Our lives are pregnant with meaning and therefore everything we do, in every moment, has meaning. We have the freedom to make decisions out of love for whatever is in our hearts. When we stop to look at the reasons for our decisions, we will always find meaning. But it takes time to reflect; and even though there s as much time as there ever was, it seems as if less and less is available to us. Taking time back is the first step in opening ourselves to meaning. But where has all the time gone?

To begin with, technology is a great time stealer. I confess to remembering the time before telephone answering machines. People either got hold of one another, or they didn t. There were no cell phones attaching themselves to our every move, nor was there email or voice mail. People at home and at work took messages and left notes ”on paper, no less! As a result there was spaciousness to decide when, and even whether, we returned the call. There was spaciousness to think, to consider, and to contemplate our decisions ”both simple and complex.

In twenty-five years, the entire world of communication has turned things around. If we don t respond instantly to an email or a cell-phone call it can be tantamount to personal betrayal or professional ineptitude. Technology, which is supposed to make life easier, has added a whole new layer of obligations. If we re not really careful, it controls us.

There are, of course, good things about it all: a revival of the written word via email; access to enormous amounts of information via the Web; greater accessibility via cell phones in case of emergencies; and, thanks to voice mail, no more missed messages of importance. But unless we do so purposefully, there is nowhere to hide from it all.

I know many people, including family members , friends, and colleagues, who are completely addicted to their cell phone. They take it everywhere: on walks, shopping, driving (even where it is against the law), to restaurants , and, yes, to the movies, where, regrettably, they often forget to turn it off. Their cell phone seems not only to function as an appendage of their body, it provides them with a symbol of their place in the world. In short, Can you hear me now? has become one of their mantras for living and they don t go anywhere without their cell phone. While they may remain connected at all times, one of the unintended consequences of this technology is that so are we. Think about how many times you have been forced to listen to a cell phone conversation in public ”details about business or personal matters that you really didn t need or want to hear?

What about our reliance on email as a way of staying connected and, more insidiously, obligated ? How many people do you know who appear to be hard-wired to their email account? They couldn t imagine a day going by without checking it? I suspect this is true of more and more of us; we are linked to outside obligations in ways that define much of the time of our lives. There is great possibility in this and also great burden . It s extremely important that we recognize the difference and know when we are responding in ways that undermine our connection to meaning.

It all comes down to awareness. In this regard, it has been said that it is more important to be aware than it is to be smart. [ 3] To be aware is to know meaning. To be aware takes time. If our lives are propelled by nothing but things piling up to respond to or the passive preoccupation with television, we lose out on meaning. We have to see, hear, smell, touch, and taste meaning if it s going to exist in our lives.

All that is good and beautiful in the past is safely preserved in that past. On the other hand, so long as life remains, all guilt and all evil is still redeemable . . . this is not the case of a finished film . . . or an already existent film which is merely being unrolled. Rather, the film of this world is just being shot. Which means nothing more or less than that the future ”happily ”still remains to be shaped; that is, it is at the disposal of man s responsibility. [ 4 ]

There are as many shades of meaning as there are colors. And nobody can determine meaning for someone else. Detecting the meaning of life s moments is a personal responsibility, one that cannot be simply delegated to another. This is the case no matter how much we would like to do so. Like it or not, if we are aware that we re in a lousy job but we need to pay the rent, the job has meaning. This doesn t mean that we resign ourselves to lifelong lousy jobs; it means there is meaning in the one we have right now. If we hate our boss because she s demanding and unappreciative, we can either be demanding and unappreciative right back or try to discover a life lesson in our predicament. Maybe the boss is trying too hard to succeed; maybe we re hearing a parental voice from our past and not her at all; maybe we have an opportunity to practice our diplomatic skills with a difficult person. Or, maybe we really are in a job that is not right for us!

In Man s Search for Meaning, Frankl describes a case in which he met with a high-ranking American diplomat at his office in Vienna, presumably to continue psychoanalytic treatment that this person had begun five years earlier in New York City. [ 5] At the outset, Dr. Frankl asked the diplomat why he thought that he should undergo analysis, and why it had started in the first place. It turned out that this patient had been discontented with his career and found it most difficult to comply with American foreign policy. His analyst, however, had told him again and again that he should to try to reconcile himself with his father, because his employer (the U.S. government) and his superiors were nothing but father figures and, consequently, his dissatisfaction with his job was due to hatred he unconsciously harbored toward his father.

For five years, the diplomat had been prompted to accept this interpretation of his plight and he became increasingly confused ”unable to see the forest of reality for the trees of symbols and images. After a few interviews with Dr. Frankl, it was clear that the diplomat s real problem was that his will to meaning was being frustrated by his vocation and that he actually longed to be engaged in some other kind of work. In the end, he decided to give up his profession and embark on another one, which, as it turned out, proved to be very gratifying to him. In truth, his anguish had not been because of his father but a result of his own inability to choose work that had true meaning for him.

If we open ourselves to being aware of the many possibilities, we open ourselves to meaning. We also have to open ourselves to our own integrity and authenticity, which is akin to living and working with meaning. Unfortunately, there s not always support for us to do so, especially in the workplace. To be sure, the roots of this complex issue run deep into the soil (and soul) of our postmodern culture. Our integrity, our search for deeper purpose and meaning can take a bruising when held up against the search for more and more money. Think, for instance, about the injury we all feel when the media exposes corporate scandals and the collateral damage that always accompanies them. To be sure, it s important to know what we are up against when we take the time and the awareness to contemplate the meaning of meaning in our lives.

It is life itself that invites us to discover meaning, and when we live our lives with awareness, we express meaning in everything we do. Webster s Third New International Dictionary lists more than twenty definitions for the word work and more than a hundred other words or phrases that begin with the word work . But it s the first definition with its two small root words, to do, that illustrates the meaning of them all. Whatever we do has meaning, whether it s a workout or a work of art.

Life retains its meaning under any conditions. It remains meaningful literally up to its last moment, up to one s last breath . [ 6 ]

Knowing why we do things, however, is essential. Knowing why we do things is the beginning of real freedom and real meaning in our lives. If we delve deep enough we ll get to the two things that motivate us most: love and conscience. Frankl described these as intuitive capabilities: things we do without thinking, things that define us at our deepest level. The truth, he wrote in Man s Search for Meaning, is that love is the ultimate and the highest goal to which man can aspire.

It s not always easy to trace where love and conscience come into play in our lives, but if we stop a moment to explore our decisions, they surface clearly: We work nights so we can be with our kids in the morning and see them off to school. We grow vegetables organically to provide healthy food for the community. We operate a small business that offers employment to three people year-round in a difficult economy. We write poems and send them to friends. We consult with others to help them more effectively cope with stress. We teach sailing to inner-city kids . We manage a corporation with an emphasis on fair wages for workers abroad. We make quilts for families who are homeless. We work at a job we don t love because it gives us time to do something we do love. We organize affordable housing in our community. We donate a thousand dollars to a local charity. We put a dollar in an outstretched hand. We build energy-efficient straw bale houses . We wait tables so we can be onstage, raise our kids, feed our dog, pay the light bill. It all comes down to love and conscience. And when we see how our world is connected in this way, we can name why and know meaning.

Do you remember from the last chapter –ystein Skalleberg s revolutionary start of it, Joy is a part of it, Love is the heart of it. How many organizations, in any sector, do you know that place the notion of love (not romantic love) at the heart of its credo? Now you know why the Skaltek work environment is unique and why Skalleberg s formula is so revolutionary. formula for building a company culture? To refresh your memory, here it is again: Confidence is the

The world is full of good deeds and the opportunity to do good deeds. When we don t do them, it s often out of fear. Fear of losing something: our status, our loved one, our job, our security, our sense of identity; our place in the world. The notion of fear at work and in the workplace has received considerable attention over the years. In fact, driving fear out of the workplace has long been a core principle of total quality management, but it remains a formidable challenge that has yet to be resolved. [ 7] Against this backdrop, approaches to assist individuals work through fear, as well as to help executives and managers become fearless, are readily available to meet this challenge. [ 8 ]

In the 1991 film Defending Your Life, director/writer Albert Brooks plays Dan Miller, a successful business executive who takes delivery on a new BMW and plows it into a bus while trying to adjust the CD player. Dan finds himself dead, but awake, in a place called Judgment City, a heavenly way station that Roger Ebert, the film critic, described as run along the lines that would be recommended by a good MBA program. And it is in Judgment City s courtroom where Dan must try to explain and defend his life, particularly those moments, shown on video, when fear was most evident in his actions. Now consider the following dialogue that takes place between Dan and his defense attorney, Bob Diamond ( played by Rip Torn):

Bob Diamond: Being from earth as you are and using as little of your brain as you do, your life has pretty much been devoted to dealing with fear.

Dan Miller: It has?

Bob Diamond: Everybody on earth deals with fear. That s what little brains do.

. . .

Bob Diamond: Did you ever have friends whose stomachs hurt?

Dan Miller: Every one of them.

Bob Diamond: It s fear. Fear is like a giant fog. It sits on your brain and blocks everything. Real feeling, true happiness, real joy, they can t get through that fog. But you lift it and buddy you re in for the ride of your life.

What lessons about detecting the meaning of life s moments are illustrated in this dialogue? For one thing, fear is depicted as the metaphorical fog that blinds one s search for meaning. Fear, in this context, relates to our inability to actualize creative expression, to experience new situations and relationships with others, and to change our attitude toward something or someone. According to Frankl, these are all sources of authentic meaning. I should point out that courage is not the absence of fear but the willingness and ability to walk through the fear ”to tread, if you will, into the darkness of life s labyrinth of meaning. And it is during the worst of times, including inescapable hardship and suffering, that our courage is put to its greatest test.

Over and over again, from those who have lost everything we learn that the worst of times is often the catalyst for the best of times. What we learn from Viktor Frankl s life and work is that even the most profound grief and intolerable circumstances can open us to meaning. And so can even the smallest of moments. All we have to do is take back the time in our lives, pay attention to the details and know why.

In the concentration camps,. . . in this living laboratory and on this testing ground, we watched and witnessed some of our comrades behave like swine while others behaved like saints. Man has both potentials within himself; which one is actualized depends on decisions but not on conditions. [ 9 ]

Sometimes we have to approach the search for meaning from another perspective. We have to know we don t know and start from there. We have to let meaning find us. This seems to be difficult as we grow older, especially at midlife when we encounter a critical crossroads on the path to meaning. Rather than having a so-called midlife crisis, writes Mark Gerzon in his book Coming Into Our Own: Understanding the Adult Metamorphosis, we can begin a search for deeper love, purpose, and meaning that becomes possible in life s second half. [ 10] Envisioning life, including our work life, as a quest, not a crisis, after midlife is an opportunity that holds great potency for all, including the growing number of baby boomers on the horizon of old age.

With increases in life expectancy and leisure time in their postretirement years, more people are beginning to ask the existential question: Is that all there is? At the same time, there are more people who are retiring at an earlier age for various reasons. Some people retire voluntarily, while others have been forced into retirement through downsizing, mergers, and the like. The increased amount of time that is becoming available to people under each of these scenarios is raising awareness of many meaning-centered questions. Indeed, the stories of retired thirty-somethings from Silicon Valley (while they obviously are now rare occurrences due to shifts in economic conditions) illustrate the dichotomy that can exist between success and fulfillment. Isolation, depression, and other symptoms of these lost souls among the nouveau riche appear to run counter to conventional wisdom. How could monetary wealth, and the time to do whatever you would want, be associated with a lack of personal meaning?

Retirement at later stages of life demands similar attention to questions of meaning, especially due to the extended life expectancy that workers in Western society now enjoy. Why is it, for instance, that some workers seem to retire from life while others simply transform or redesign themselves for new and meaningful challenges in living and work? The life and legacy of Viktor Frankl have taught us, in no uncertain terms, to approach the aging process from a position of personal strength and in a way that respects the dignity of the human spirit. The post-midlife years of Frankl, who had not retired at over 90 years of age, provides a window for us to see how important the will to meaning can actually be throughout one s lifetime.

All things being equal, I suspect that the new balanced scorecard of the twenty-first century will be concerned more with success at making a life than it will be about making a living. Hence, as people become more aware of their own mortality, as well as their commitment to meaningful values (i.e., their will to meaning), they will be more likely to consider the kind of personal legacy they would like to leave behind. To Frankl, this kind of questioning is a manifestation of being truly human: No ant, no bee, no animal will ever raise the question of whether or not its existence has a meaning, but man does. It s his privilege that he cares for a meaning to his existence. He is not only searching for such a meaning, but he is even entitled to it . . . After all, it s a sign of intellectual honesty and sincerity . [ 11]

By reflecting upon our existence and seeking to detect the meaning of life s moments, we also create the opportunity to draft our personal legacy, albeit as a work in progress. There are a number of simple and practical exercises that can be used for this purpose; let me now introduce you to some of them. Because I am blessed with living in the mountains of northern New Mexico, I like to call the first exercise High Altitude Thinking.

Imagine that you are sitting high on a mountain peak overlooking your life. From this distance, you can see all of the roads that you have taken, all of the stops that you have made, all of the people that you have encountered , all of the things that you have done or experienced in your life. Like a mapmaker, draw the map of your life, using various symbols to highlight the milestones in each of the above areas. Ask yourself the significance or meaning of each milestone; after all, you ve identified it as such, so now you should be able to determine why it is what it is. Next , weave together the pieces of your life s map, referring to the milestones as the fabric to be used, and create a quilt that symbolizes your life and work. Embedded in your life/work quilt are the threads of your personal legacy.

Another exercise that can be used as a catalyst for you to reflect upon your life, including your work life, and help you chart your path to a meaningful existence takes a much different approach. Like Albert Brook s character Dan Miller in the movie Defending Your Life, imagine that you have died. However, rather than imagining yourself in Judgment City, put yourself in the position of having to write your own obituary for the local newspaper. What would you say? In other words, how do you want to be remembered ? What are the most important things that you experienced in your life? Since the newspaper editor has given you a one-page space limitation, you must be as clear and succinct about your message as possible.

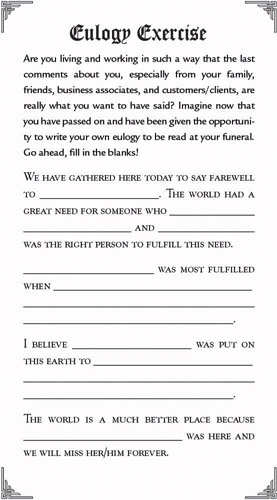

An alternative to the Obituary Exercise is depicted in the Eulogy Exercise, on the next page. In this exercise, you are asked to fill in the blanks on the form, again making sure that the last comments about you, recited at your funeral, are really what you want said! [ 12] You have been given the unique opportunity to write your own eulogy, so make sure that you incorporate the things that matter the most to you. Did you live and work with meaning? Now, assume that someone else wrote your eulogy. What would be different about it? Remember Scrooge s experience in the classic tale A Christmas Carol ? What would your encounter with the Ghost of Christmas Future, in which you get a glimpse of your destiny, be like? How would people remember you, talk about you?

Each of these exercises will not only help you reflect upon your life/work but also detect what is most meaningful to you. In all instances, you are being asked to step up in some way (the latter two exercises are more of an out-of-body experience) and see the big picture of your life. You may or may not like what you see. Yet, these exercises also provide you with a chance to consider your life s ultimate meaning, as Frankl would say. Irrespective of your religious or spiritual persuasion, ultimate meaning is a metaphysical concept, one that clearly has its roots and value in spiritual matters. In his introduction to The Doctor and the Soul, Frankl wrote the following: Life is a task. The religious man differs from the apparently irreligious man only by experiencing his existence not simply as a task, but as a mission. Now ask yourself truthfully: Is your life a task or a mission? What about your work?

As you map your life s path, write your obituary or eulogy, draft your personal legacy, or weave together your life quilt, keep these life-affirming questions in mind. By remaining aware of the need to detect and learn from the meaning of life s moments, you ensure that you do not become a prisoner of your thoughts. And by focusing on meaning s big picture, your search for ultimate meaning begins but never ends.

| |

Recall a situation in your work life in which you were forced to deal with the fear of change (this may even be your situation today). Perhaps you were facing a down-sizing or merger. Perhaps you were confronted with a new leadership/management style or the need for job re-training. Or, perhaps you were facing retirement. How did you first come to recognize the fear of change? What, if anything, did you actually do about it? As you think about the situation now, what did you learn from it? In particular, what did you learn about your ability to confront your fears and respond to change?

Meaning Question: How is your work like a mission rather than a series of tasks ?

Imagine that you have written your autobiography ”with details about your life and work ”and it is now on The New York Times bestseller list. What is the title of your autobiography? Name and briefly describe the chapters that are in your autobiography. Who are the people included in your Acknowledgements section?

| |

[ 1] Viktor E. Frankl, Man s Search for Meaning: An Introduction to Logotherapy (Boston: Beacon Press, 4th Edition, 1992), p. 114.

[ 2 ] Frankl, Man s Search for Meaning, p. 115.

[ 3] See, for example, Phil Jackson and Hugh Delehanty, Sacred Hoops: Spiritual Lessons of a Hardwood Warrior (New York: Hyperion, 1995).

[ 4 ] Viktor E. Frankl, keynote address, Evolution of Psychotherapy Conference, Anaheim, California, December 12 “16, 1990.

[ 5] Frankl, Man s Search for Meaning, p. 107.

[ 6 ] Viktor E. Frankl, The Doctor and the Soul: From Psychotherapy to Logotherapy (New York: Random House, 1986), p. xix.

[ 7] Kathleen D. Ryan and Daniel K. Oestreich, Driving Fear Out of the Workplace: Creating the High-Trust, High-Performance Organization (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1998).

[ 8 ] See, for example: Susan Jeffers, Feel the Fear and Do It Anyway (New York: Ballantine Books, 1988); and Alan Downs , The Fearless Executive (New York: AMACOM Books, 2000).

[ 9 ] Frankl, Man s Search for Meaning, p. 135.

[ 10] Mark Gerzon, Coming Into Our Own: Understanding the Adult Metamorphosis (New York: Delacorte Press, 1992).

[ 11] See Frankl, The Doctor and the Soul, p. 26.

[ 12] I m indebted to Art Jackson for introducing me to this particular exercise.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 35