Using the Police to Watch for Bad Guys

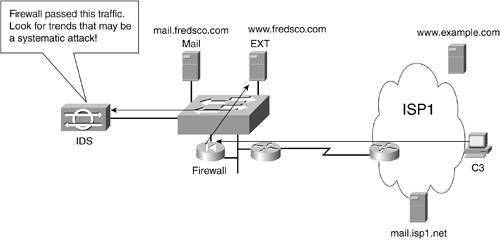

| Even with neighborhood watch programs, communities still have the police. Although the police can't stay in your neighborhood all day long, they can do a bunch of things to prevent crime, as well as to prevent crimes from recurring. They can arrest suspects and question them, look into their criminal records, and prosecute them as necessary. The police can go to great lengths to prevent future crimes, in part by looking at how past crimes were committed and stopping similar crimes in the future. Firewalls prevent the types of flows that are known to be potentially harmful. However, firewalls do let packets into and out of an enterprise network. So, in addition to a firewall, networks need other security tools. These tools watch for known patterns of illegal network activityactivity that is intended to look like normal activity so that it can get past the firewall. In the next two sections, you'll read about a couple of tools that watch for trends, compare those to known illegal network activity, and do something to prevent problems as a result of the activity. Watching for Wolves in Sheep's ClothingIn a spy movie, the spy might need to get in to look around a big office campus. He might cut the phone lines to the building complex and then show up in a telephone repair truck saying, "Hi, our monitoring center noticed that a telephone line was cut. Want to let me in to fix it?" The security guard waves him through because he knows that the telephones have been acting up. Whoops! The bad guy is now free to roam around and do his spying! In networking, intrusion detection systems (IDSs) look out for the equivalent of spies who are impersonating a legitimate user. IDSs watch the packets that the firewall allows through, and they look for things in the packets that might mean someone is trying to trick the firewall, get their packets through the firewall, and do bad things to the servers and hosts in your network. Whereas it's easy to think of a spy from the movie posing as a telephone repairman, it's hard to understand how a cracker might make his packets look like packets sent by a legitimate user, but still use those packets to do harm. (The term cracker refers to someone who purposefully tries to cause problems with devices on a network; the term hacker refers to someone who might be trying to break into a network but does not intend to cause problems.) In some cases, the cracker might do something that causes a server to fail; that's called a denial of service attack. In other cases, the cracker actually puts programs on a computer, hoping to harm the computer, or possibly steal information. In that case, the programs that the cracker puts on the servers are called viruses. Although most people have a hard time fully understanding how these tricks are done, it does happen. In fact, Microsoft has offered rewards into the hundreds of thousands of dollars for leads to help the police find and arrest crackers who create particularly harmful viruses. Some IDS devices sit in the network, watching packets that pass over a LAN, whereas others are software that sits on the servers. The IDSs on the network are called network-based IDSs, and those on the host are called (you guessed it) host-based IDSs. Figure 18-9 shows the typical location of a network-based IDS. Figure 18-9. Watching for Patterns with a Network-Based IDS For a network-based IDS to work correctly, the LAN switch must be configured so that traffic to and from the firewall is copied and sent to the IDS. That way, the IDS can review the packets, searching for trends that might look like a cracker trying a cracker trick. It's like the difference between a security guard who just passed the phone repair truck through, versus one who passes the truck through but then sends someone to check up on the repairman and follow him around the building. Avoiding Catching ColdComputers can get viruses, just like people can. As mentioned earlier, a computer virus is a file, typically a program, which can cause problems after a copy of the virus gets on your computer. The file often gets on your computer via e-mail or web browsing. Just like real viruses, a computer virus can make your computer really sick, a little sick, or you might not even know that you have a virus. Often times, like real viruses, after your computer gets a virus, it can infect other computers. To combat viruses, people install anti-virus software on end user computers as well as on servers. This software looks at the files copied to the computer to make sure there are no known viruses. For instance, some e-mails have files attached to them. The anti-virus software looks at the files, comparing the contents to a list of known viruses. If the file contains a virus, the anti-virus software either deletes the file or puts it somewhere safe. Profiling What the Bad Guys Want to DoWhen the police are patrolling around the neighborhood, they know what general things to look out for because that's what they were trained to do. For instance, if there's been a rash of bank robberies lately using a green van as the getaway car, you know the police will be looking for green vans in particular. In the real world, police usually call that profiling. IDS systems and anti-virus software do a form of profiling, but in networking, the term signature is used. Whenever a new way to hack into the network is found, or whenever a new virus is discovered, the vendors that sell the IDS and anti-virus software create a signature for that problem. The signature tells the IDS or anti-virus software what to look for to identify the problem. As long as a network engineer updates the IDS to know about the latest signatures, the IDS will be well prepared for all known problems. Similarly, most PCs with proper security have their anti-virus software updated regularly with new virus signatures. |

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 173