158 - Radiographic, Computed Tomographic, and Magnetic Resonance Investigation of the Mediastinum

Editors: Shields, Thomas W.; LoCicero, Joseph; Ponn, Ronald B.; Rusch, Valerie W.

Title: General Thoracic Surgery, 6th Edition

Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Volume II > The Mediastinum > Section XXIX - Primary Mediastinal Tumors and Syndromes Associated with Mediastinal Lesions > Chapter 187 - Nonseminomatous Malignant Germ Cell Tumors of the Mediastinum

Chapter 187

Nonseminomatous Malignant Germ Cell Tumors of the Mediastinum

John D. Hainsworth

F. Anthony Greco

Mediastinal germ cell tumors are rare neoplasms that occur almost exclusively in young men. Although rare, these tumors are of special interest because they are potentially curable with optimal therapy. Several histologic subtypes occur in the mediastinum. With the exception of pure seminomas, these tumors are grouped together as nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. Because the management of these histologic subtypes is identical in most instances, they are considered together in this chapter.

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

Mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors were first described by Kantrowitz (1934). Laipply and Shipley (1945), and Caes and Cragg (1947) also described these tumors. The first speculation concerning the oncogenesis of extragonadal malignant germ cell tumors was by Schlumberger (1946), who postulated that these neoplasms arise from primitive rests of totipotential cells that become detached from the blastula or morula during embryogenesis. Subsequently, Fine and associates (1962) proposed that extragonadal malignant germ cell tumors arise from primitive germ cells in the endoderm of the yolk sac or from the urogenital ridge, which fail to completely migrate into the scrotum during development. At present, both hypotheses remain unproven, and the oncogenesis of extragonadal and malignant germ cell tumors remains uncertain. Although either hypothesis can explain the occurrence of extragonadal malignant germ cell neoplasms in the retroperitoneum or mediastinum, the occasional occurrence of these tumors in other locations, such as in the pineal or sacrococcygeal areas, is best explained by Schlumberger's hypothesis.

Although the concept of an extragonadal site of origin of these neoplasms is generally accepted, a few reports have raised the possibility that some of these neoplasms are actually metastatic lesions from an occult primary tumor in the gonad. Patients with small testicular primaries, carcinoma in situ, or fibrous scars in the testicle, thought to represent sites of regressed primary tumors, have been reported by Meares and Briggs (1972), as well as by Azzopardi (1961), Rather (1954), and Daugaard (1987) and their associates. However, these findings have been rare in large autopsy series reported by Oberman and Libcke (1964) and Cox (1975), as well as by Johnson (1973) and Luna (1976) and their associates. In addition, large numbers of patients with malignant mediastinal germ cell tumors have had long-term survival after either mediastinal irradiation for pure seminoma or combination chemotherapy for nonseminomatous tumors. In these patients, testicular recurrences have not been a clinical problem. Primary malignant mediastinal germ cell tumors therefore should be accepted as a distinct clinical entity. The coexistence of an occult testicular primary is rare and should not influence the treatment of these patients.

Although the cause of malignant mediastinal germ cell neoplasms is unknown, men with Klinefelter's syndrome have a peculiar propensity to develop these tumors. Klinefelter's syndrome is a relatively common chromosomal abnormality characterized by hypogonadism, azoospermia, and elevated gonadotropin levels in association with an extra X chromosome. Scheike and associates (1973) have described a slightly increased incidence of breast cancer in these men, but a predisposition to other malignancies has not been observed. Richenstein (1972) first reported the occurrence of an extragonadal germ cell tumor in a patient with Klinefelter's syndrome. Since that time, this association has been confirmed by multiple investigators, including Doll (1976), Sogge (1979), Floret (1979), Curry (1981), McNeil (1981), Turner (1981), Chaussain (1980), Schimke (1983), and Lachman (1986) and their associates. Four of 22 consecutive patients (18%) treated by Nichols and associates (1987) for mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors had karyotypic confirmation of Klinefelter's syndrome. For unexplained reasons, the average age of patients with Klinefelter's syndrome who develop extragonadal germ cell tumors is approximately 10 years younger than that of those developing this tumor in the absence of Klinefelter's syndrome. Testicular germ cell neoplasms

P.2718

have rarely been reported in association with Klinefelter's syndrome; therefore, the association with malignant mediastinal germ cell neoplasms seems specific.

The explanation for this association is unknown, but it is reasonable to assume that the chromosomal abnormality plays some role. Increasing evidence indicates that underlying germ cell defects are common in men who develop germ cell tumors. Clinical history of infertility is common, and Carroll and colleagues (1987) have described abnormal testicular biopsy findings, including decreased spermatogenesis, interstitial edema, and peritubular fibrosis. In addition, Hartmann and associates (2001a) have recognized an increased incidence of testicular germ cell tumors in patients who have been successfully treated for extragonadal germ cell tumor. These data suggest that either a congenital or an acquired germ cell defect contributes not only to defective spermatogenesis but also to the development of extragonadal germ cell tumors.

INCIDENCE

Malignant germ cell tumors of the mediastinum are uncommon and have accounted for approximately 1% to 5% of all germ cell neoplasms in series reported by Collins and Pugh (1964) and by Einhorn and Williams (1980). In early series of mediastinal tumors reported by Sabiston and Scott (1952), Ringertz and Lidholm (1956), and Boyd and Midell (1968), and Hodge (1959), Heimburger (1963), and Rubush (1973) and their co-workers, these tumors accounted for 3% to 10% of tumors originating in the mediastinum. However, it is probable that the true incidence of these neoplasms has been underestimated. The histology of these tumors may be similar to that of other malignant mediastinal tumors, including malignant thymoma and high-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Patients with clinical characteristics of extragonadal malignant germ cell tumors in whom the initial pathologic diagnosis was poorly differentiated carcinoma have been reported by us and Vaughn (1986) and by Fox and associates (1979). Some of these patients had tumors that were highly sensitive to chemotherapy for germ cell tumors.

More recently, molecular genetic analysis of mediastinal tumors from young men with poorly differentiated carcinoma has allowed the definitive diagnosis of mediastinal germ cell tumor. Motzer and colleagues (1995) detected the i(12p) chromosomal abnormality in 12 of 40 such patients. This chromosomal marker was first identified by Bosl and associates (1989) and is known to be specific for germ cell tumors.

Malignant mediastinal germ cell tumors occur almost exclusively in men; in a review of 184 such tumors by Moran and Suster (1997), all 184 tumors occurred in men. Fewer than 30 cases in women have been reported in the literature by Pachter and Lattes (1964), Kersh and Hazra (1985), Peison (1970), Fanger and MacAndrew (1952), and Martini (1974), Knapp (1985), El-Domeiri (1968), Polansky (1979), Sandhaus (1981), and Moriconi (1985) and their associates. The histology spectrum and biology of malignant mediastinal germ cell tumors seem similar in women and men.

|

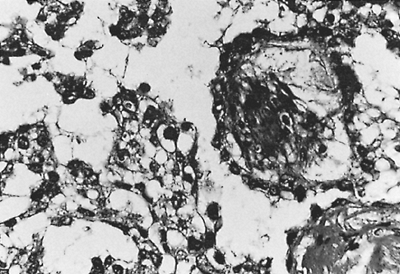

Fig. 187-1. Photomicrograph of a yolk sac tumor. The tumor cells form papillary projections into microcystic spaces. Beneath the tumor cells is connective tissue containing small blood vessels. From Williams SD, et al: Treatment of disseminated germ cell tumors with cisplatin, bleomydin, and either vinblastine or etoposide. N Engl J Med 316: 1435, 1987. With permission. |

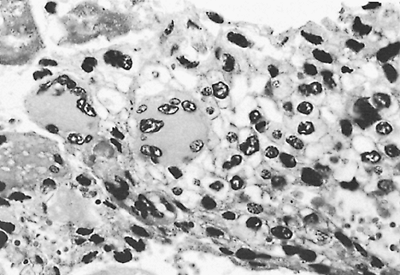

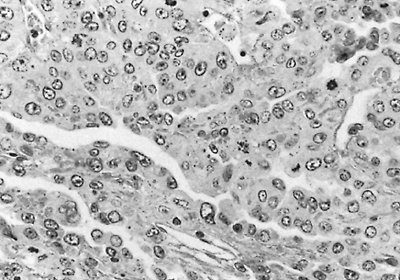

Approximately 50% of mediastinal germ cell tumors have nonseminomatous histologies, while 50% are pure seminomas. The incidence of the various nonseminomatous histologies has varied in published series, most of which have contained fewer than 30 patients. In a large, retrospective series composed of 229 cases seen at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology and Mount Sinai Medical Center in Miami, Moran and Suster (1997) reported the following incidences of nonseminomatous histologies: teratocarcinoma, 41%; endodermal sinus (yolk sac) tumor, 35% (Fig. 187-1); choriocarcinoma, 7% (Fig. 187-2); and embryonal carcinoma, 6% (Fig. 187-3). Eleven percent of tumors contained a mixture of histologies. Nongerm cell components, usually sarcoma or epithelial carcinoma, were found in 26 of 45 teratocarcinomas (58%).

|

Fig. 187-2. Photomicrograph of a choriocarcinoma. The tumor is composed of syncytiotrophoblasts and cytotrophoblasts. The syncytiotrophoblasts are the large multinucleated giant cells in the center and to the left of the center. The cytotrophoblasts are the single cells with fairly distinct cytoplasmic cell borders in the right side of the field. |

|

Fig. 187-3. Photomicrograph of a typical embryonal carcinoma. The tumor is composed of large cells with slitlike spaces. The nuclei are large, and mitotic figures are present. |

P.2719

The pathologic features of mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors differ in several ways when compared with their counterparts arising in the testis. First, the occurrence of pure endodermal sinus tumor is extremely rare in the testis, whereas it accounts for up to 35% of mediastinal nonseminomas. Second, the incidence of embryonal carcinoma is much higher in the testis than in the mediastinum. Finally, the occurrence of nongerm cell histologies within mediastinal germ cell tumors is more common than in testicular tumors.

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Malignant mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors are characterized clinically by rapid local growth and early metastasis to distant sites. At the time of diagnosis, most patients have symptoms caused by compression, invasion, or both, of local mediastinal structures. In addition, large series reported by one of us (JDH) (1982), Israel (1985), and Logothetis (1985) and respective colleagues have shown that 85% to 95% of these patients have at least one site of metastatic disease at diagnosis, and that presenting symptoms are frequently caused by metastases. Common sites of metastases include lung, pleura, lymph nodes (supraclavicular and retroperitoneal), and liver. Bone, brain, and kidneys are less frequently involved. Sickles and associates (1974) have noted that patients whose tumors contain choriocarcinoma elements may experience catastrophic events related to uncontrolled hemorrhage, such as intracranial hemorrhage or massive hemoptysis. Gynecomastia is present in some patients who have high serum levels of human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG). Constitutional symptoms, such as weight loss, fever, and weakness, are more common in patients with nonseminomatous tumors than in those with pure seminoma.

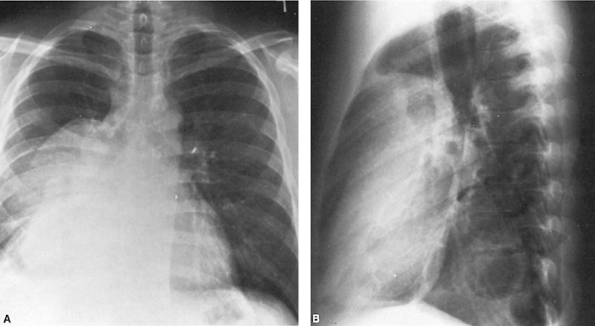

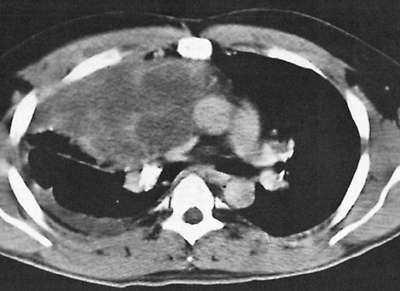

The chest radiograph at diagnosis usually reveals a large anterior mediastinal mass, but shows no features that distinguish nonseminomatous germ cell tumors from other mediastinal neoplasms (Fig. 187-4). Levitt and colleagues (1984) reported that computed tomography (CT) usually

P.2720

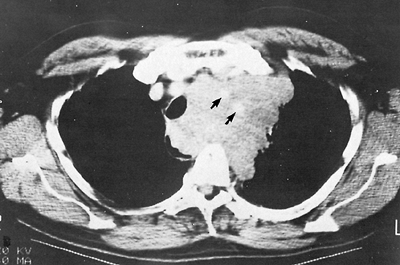

shows an inhomogeneous mass with multiple areas of necrosis and hemorrhage (Fig. 187-5), differing from the usually homogeneous appearance of pure mediastinal seminoma. Envelopment of the blood vessels is also often present (Fig. 187-6).

|

Fig. 187-4. A, B. Posteroanterior and lateral chest radiographs of a large anterior mediastinal mass. Right pleural effusion is present. The -fetoprotein level was 35,000 U, but the human chorionic gonadotropin level was normal. Biopsy revealed mixed embryonal and endodermal sinus (yolk sac) elements. Complete remission followed combination chemotherapy of bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin. |

|

Fig. 187-5. CT scan of a malignant nonseminomatous germ cell tumor of the anterior mediastinum reveals inhomogeneous anterior mediastinal mass in contrast to homogeneous density of a seminoma (as seen in Fig. 187-2). Pleural effusion also is demonstrated in the right bronchus. |

As in advanced testicular nonseminomatous germ cell tumors, approximately 90% of patients with mediastinal malignant nonseminomatous germ cell tumors have elevated levels of HCG or -fetoprotein. In a large series reported by Nichols and colleagues (1990), -fetoprotein was most frequently abnormal, and was elevated either alone or in conjunction with HCG in 80% of patients. HCG is elevated in only 30% to 35% of patients. This marker pattern differs slightly from that observed in nonseminomatous testicular tumors, where both markers are elevated with equal frequency. Elevation of -fetoprotein levels always indicate the presence of nonseminomatous elements within the tumor. These patients should be treated for nonseminomatous germ cell tumor, even if the biopsy shows pure seminoma. Elevation of an HCG level above 100 ng/mL is unusual in pure seminoma, and also suggests the presence of nonseminomatous elements. Serum lactic dehydrogenase is also elevated in 80% to 90% of patients.

|

Fig. 187-6. CT scan of malignant nonseminomatous germ cell tumor encasing the great vessels (arrows) and displacement of the trachea to the right. |

ASSOCIATED SYNDROMES

The association of nonseminomatous mediastinal germinal tumors with a variety of hematologic malignancies was first characterized by Nichols and associates (1985, 1990) and is now well recognized. Hematologic diagnoses included acute nonlymphocytic leukemia, acute lymphocytic leukemia, erythroleukemia, acute megakaryocytic leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, and malignant histiocytosis. In a review of 635 patients with extragonadal germ cell tumors, Hartmann and associates (2000) identified 17 patients who developed hematologic malignancies at a median of 6 months after the diagnosis of the germ cell tumor. All hematologic neoplasms developed in the 287 patients with mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors, for a 2% incidence in this group. Median survival was only 5 months after diagnosis of the hematologic disorder, and no patient survived for more than 2 years.

Most current evidence indicates that the hematologic neoplasms in this setting are not treatment related, but rather arise from clones of malignant lymphoblasts or myeloblasts contained within the mediastinal germ cell tumor. Several patients with identical karyotypic abnormalities in the malignant germ cells and leukemic cells have been reported by Chaganti (1989), Landanyi (1990), and Orazi (1993) and their colleagues. In most reported patients, the shared karyotypic abnormality was the germ cell tumor specific isochromosome of the short arm of chromosome 12 [i(12p)] identified by Bosl and associates (1989). The ability of germ cell tumors to produce a variety of histologic phenotypes is well recognized clinically. In addition to sarcoma, adenocarcinoma, and neuroendocrine carcinoma, foci of lymphoblasts occasionally have been described. Although the common origin of these associated neoplasms seems likely, the specific association of hematopoietic malignancies and mediastinal malignant nonseminomatous germ cell tumors, rather than with all germ cell tumors, is unexplained.

In addition to hematologic malignancies, Garnick and Griffin (1983) and Helman and co-workers (1984) have reported several cases of idiopathic thrombocytopenia in association with malignant mediastinal germ cell tumors. In these patients, normal numbers of megakaryocytes were present in the bone marrow; however, no immune destruction of platelets could be demonstrated. Thrombocytopenia was refractory to treatment with prednisone or splenectomy and made treatment of the underlying neoplasm extremely difficult. At present, the cause of this syndrome is unknown.

P.2721

Other unusual associated syndromes also have been reported. Myers and associates (1988) reported a single case of mediastinal endodermal sinus tumor associated with the hemophagocytic syndrome. This patient had a proliferation of benign, mature macrophages with prominent hemophagocytosis seen in the bone marrow. In spite of a partial response to chemotherapy, the hemophagocytic syndrome persisted, and the patient subsequently died of progressive tumor. Chariot and associates (1991) reported a patient with systemic mast cell disease in association with a mediastinal embryonal carcinoma. Hypotension, syncope, and a gastric hemorrhage were associated with a circulating heparin-like anticoagulant. The syndrome resolved with successful treatment of the germ cell tumor.

PRETREATMENT EVALUATION

The diagnosis of malignant mediastinal germ cell tumor should be considered in all young men with an anterior mediastinal mass. Initial evaluation, in addition to physical examination and routine laboratory studies, should include CT of the chest and abdomen and determination of serum levels of HCG and -fetoprotein. Additional symptoms suggestive of metastases should be evaluated with appropriate radiologic studies. If obvious metastases are present, histologic diagnosis should be made using the least invasive approach, because rapid initiation of systemic therapy is essential. In patients with a mediastinal mass, levels of HCG or -fetoprotein in excess of 500 ng/mL are diagnostic of malignant nonseminomatous mediastinal germ cell tumor. Patients with these findings should be treated immediately with combination chemotherapy, and the delay entailed by performing a biopsy should be avoided. Extensive mediastinal surgical procedures are contraindicated in patients with malignant nonseminomatous germ cell tumors.

TREATMENT

The futility of local treatment modalities for malignant nonseminomatous mediastinal neoplasms has been recognized since the 1970s. In a review of the literature in 1975, Cox found no reported survivors among 85 cases of mediastinal teratocarcinoma. Treatment failure in series reported by Hunt (1982), Martini (1974), and Economou (1982) and their colleagues was usually caused by the progression of distant metastases, but local treatment modalities (i.e., resection, radiation therapy, or both) also failed to provide local control. Early attempts to treat these tumors with single-agent chemotherapy or chemotherapy combinations without cisplatin produced transient responses, but also had no meaningful effect on survival.

The use of intensive cisplatin-based chemotherapy regimens developed for the treatment of advanced nonseminomatous testicular neoplasms has improved the formerly dismal outlook of patients with malignant mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. Table 187-1 summarizes the results of treatment with optimal cisplatin-based

P.2722

combination chemotherapy in reports containing 10 or more patients. The overall long-term survival rate in these optimally treated patients is 41%. Although these results represent a marked improvement, they are still inferior to the overall results in patients with metastatic testicular nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. The large bulk of most mediastinal germ cell neoplasms at the time of diagnosis accounts in part for these relatively poor results. Testicular neoplasms with far advanced, bulky metastases have comparable long-term survival rates, approximately 40% to 50%, when treated with similar cisplatin-based regimens. However, a comparison of mediastinal and testicular nonseminomatous germ cell tumors by Toner and associates (1991) revealed additional clinical differences, including lower HCG and lactic dehydrogenase levels, and more frequent endodermal sinus elements in mediastinal tumors. Therefore, it is probable that inherent biological differences also contribute to the relatively poor prognosis of patients with mediastinal malignant nonseminomatous germ cell tumors.

Table 187-1. Malignant Nonseminomatous Mediastinal Germinal Neoplasms: Results of Treatment with Cisplatin-Based Combination Chemotherapy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The treatment for mediastinal malignant nonseminomatous germ cell tumors should follow guidelines for poor-prognosis testicular cancer. Initial treatment with four courses (12 weeks) of bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin, as described by Williams and colleagues (1987) is considered standard therapy. Treatment for all histologic subtypes of mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumor should follow the same guidelines. Administration of chemotherapy at full doses and on schedule is important in obtaining optimal results.

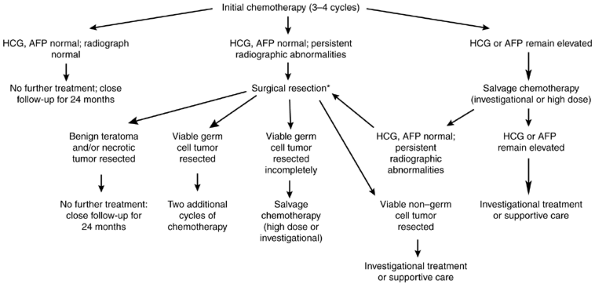

After completion of therapy, patients should be restaged with CT of the chest and abdomen and repeated testing for the serum tumor markers. Figure 187-7 diagrams the subsequent management as determined by the initial response to chemotherapy. Patients with normal CT scans and tumor markers should receive no further therapy. Approximately 20% of these patients subsequently relapse, with almost all relapses occurring during the first 2 years after therapy. Close follow-up is recommended, with monthly physical examination, chest radiography, and serum tumor markers during the first year, and bimonthly evaluations during the second year.

Surgical intervention is often necessary in patients who have normal serum tumor markers and residual mediastinal abnormalities after initial combination chemotherapy. In this setting, approximately 75% of patients have either nonviable tumor or benign teratoma with no evidence of active malignancy. However, consideration for surgical resection should not be limited to patients with normal serum levels of HCG and -fetoprotein. In a recent experience described by Ganjoo and colleagues (2000), 10 of 18 patients with persistent marker abnormalities (usually -fetoprotein <100 ng/mL) had only necrotic tumor or teratoma at resection. The importance of completely resecting residual benign, mature or immature, teratomas in these patients has been recognized. Unresected teratomas can cause further problems either by slow local growth or by subsequent malignant degeneration. Because surgical resection of necrotic tumor or fibrosis is not therapeutic, the optimal timing of

P.2723

surgical resection after chemotherapy has been debated. Some patients with only necrotic tumor remaining have delayed shrinkage of residual radiographic masses; follow-up with serial scans sometimes results in the avoidance of a major operative procedure. It is reasonable to delay resection for 2 to 3 months in patients with a partial radiographic response, as long as subsequent tumor shrinkage is observed on follow-up radiography. Tumors that fail to decrease should be resected. Patients with a large component of teratocarcinoma in the original biopsy are more likely to have residual benign teratoma that requires resection.

|

Fig. 187-7. Management of malignant nonseminomatous mediastinal germ cell tumors after completion of initial chemotherapy. *Timing of resection depends on tumor response and initial histology. AFP, -fetoprotein; HCG, human chorionic gonadotropin. |

Patients with no viable tumor found at the time of surgical resection have the same low risk for subsequent relapse as do patients achieving complete remission with chemotherapy alone. If residual viable germ cell carcinoma is completely resected after initial chemotherapy, two additional courses of chemotherapy should be administered postoperatively, because these patients have a high relapse rate and poor survival after resection alone. Patients who have residual nongerm cell histologies resected have a poor prognosis. These nongerm cell histologies have been resistant to further chemotherapy, so such patients should be followed without further therapy after resection.

Patients with persistent elevations of tumor markers after completion of initial chemotherapy have residual active carcinoma. In most instances, attempts at surgical resection are unsuccessful in these patients when either marker level is greater than 100 ng/mL, either because of inability to achieve complete resection or rapid relapse postoperatively. Salvage regimens proven effective in 20% to 30% of patients with relapsed or refractory testicular cancer are only occasionally effective in mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. In a group of 79 patients with refractory mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors reviewed by Hartmann and associates (2001b), the salvage rate was only 12%. Outcome was not substantially different in patients receiving high-dose second-line regimens versus standard-dose salvage regimens.

Although the development of cisplatin-containing chemotherapy regimens has improved the prognosis of patients with malignant nonseminomatous mediastinal germ cell tumors, these tumors continue to be fatal in the majority of patients. Novel first-line treatment approaches, including initial high-dose therapy, are currently being investigated. Further improvements in therapy will probably parallel the development of increasingly effective treatment for patients with poor prognosis testicular germ cell neoplasms.

REFERENCES

Azzopardi JG, Mostofi FK, Theiss EA: Lesions of testes observed in certain patients with widespread choriocarcinoma and related tumors. Am J Pathol 38:207, 1961.

Bosl GJ, et al: i(12p): a specific karyotypic abnormality in germ cell tumors. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 8:131, 1989.

Boyd DP, Midell AI: Mediastinal cysts and tumors: an analysis of 96 cases. Surg Clin North Am 48:493,1968.

Bukoswki RM, et al: Alternating combination chemotherapy in patients with extragonadal germ cell tumors. A Southwest Oncology Group study. Cancer 71:2631, 1993.

Caes HJ, Cragg RW: Extragenital choriocarcinoma of the male with bilateral gynecomastia report of a case. US Navy Med Bull 47:1072, 1947.

Carroll PR, et al: Testicular failure in patients with extragonadal germ cell tumors. Cancer 60:108, 1987.

Chaganti RSK, et al: Leukemic differentiation of a mediastinal germ cell tumor. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1:83, 1989.

Chariot P, et al: Systemic mast cell disease associated with primary mediastinal germ cell tumor. Am J Med 90:381, 1991.

Chaussain JL, et al: Klinefelter syndrome, tumor and sexual precocity. J Pediatr 97:607, 1980.

Collins DH, Pugh RCB: Classification and frequency of testicular tumors. Br J Urol 36(suppl):1, 1964.

Cox JD: Primary malignant germinal tumors of the mediastinum. A study of 24 cases. Cancer 36:1162, 1975.

Curry WA, et al: Klinefelter's syndrome and mediastinal germ cell neoplasms. J Urol 125:127, 1981.

Daugaard G, et al: Carcinoma-in-situ testis in patients with assumed extragonadal germ-cell tumours. Lancet 2:528, 1987.

Doll DC, Weiss RB, Evans H: Klinefelter's syndrome and extragenital seminoma. J Urol 116:675, 1976.

Dulmet EM, et al: Germ cell tumors of the mediastinum: a 30-year experience. Cancer 72:1984, 1993.

Economou JS, et al: Management of primary germ cell tumors of the mediastinum. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 83:643, 1982.

Einhorn LH, Williams SD: Management of disseminated testicular cancer. In Einhorn LH (ed): Testicular Tumors: Management and Treatment. New York: Masson, 1980, p. 117.

El-Domeiri AA, et al: Primary seminoma of the anterior mediastinum. Ann Thorac Surg 6:513, 1968.

Fanger H, MacAndrew R: Extragenital chorionepithelioma in a female arising from a mediastinal teratoma. RI Med J 35:259, 1952.

Fine F, Smith RW Jr, Pachter MR: Primary extragenital choriocarcinoma in the male subject. Case report and review of the literature. Am J Med 32:776, 1962.

Fizazi K, et al: Primary mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors: results of modern therapy including cisplatin-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 16:725, 1998.

Floret D, Renaud H, Monnet P: Sexual precocity and thoracic polyembryoma: Klinefelter syndrome? J Pediatr 94:163, 1979.

Fox RM, et al: Undifferentiated carcinoma in young men: the atypical teratoma syndrome. Lancet 1:1316, 1979.

Funes HC, et al: Mediastinal germ cell tumors treated with cisplatin, bleomycin and vinblastine (PVB) [Abstract]. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res 22:474, 1981.

Ganjoo KN, et al: Results of modern therapy for patients with mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. Cancer 88:1051, 2000.

Garnick MB, Griffin JD: Idiopathic thrombocytopenia in association with extragonadal germ cell cancer. Ann Intern Med 98:926, 1983.

Gerl A, et al: Cisplatin-based chemotherapy of primary extragonadal germ cell tumors. A single institution study. Cancer 77:526, 1996.

Goss PE, et al: Extragonadal germ cell tumors: a 14-year Toronto experience. Cancer 73:1971, 1994.

Greco FA, Vaughn WK, Hainsworth JD: Advanced poorly differentiated carcinoma of unknown primary site: recognition of a treatable syndrome. Ann Intern Med 104:547, 1986.

Gutierrez-Delgado FG, Tjulandin SA, Garin AM: Long-term results of treatment in patients with extragonadal germ cell tumours. Eur J Cancer 29A:1002, 1993.

Hainsworth JD, et al: Advanced extragonadal germ-cell tumors. Successful treatment with combination chemotherapy. Ann Intern Med 97:7, 1982.

Hartmann JT, et al: Hematologic disorders associated with primary mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst 92: 54, 2000.

Hartmann JT, et al: Incidence of metachronous testicular cancer in patients with extragonadal germ cell tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst 93: 1733, 2001a.

Hartmann JT, et al: Second-line chemotherapy in patients with relapsed extragonadal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors: results of an international multicenter analysis. J Clin Oncol 19: 1641, 2001b.

Heimburger I, Battersby JS, Vellios F: Primary neoplasms of the mediastinum: a 15 year follow-up. Arch Surg 86:978, 1963.

P.2724

Helman LJ, Ozols RF, Longo DL: Thrombocytopenia and extragonadal germ-cell neoplasm. Ann Intern Med 101:280, 1984.

Hodge J, Aponte G, McLaughlin E: Primary mediastinal tumors. J Thorac Surg 37:730, 1959.

Hunt RD, et al: Primary anterior mediastinal seminoma. Cancer 49:1658, 1982.

Israel A, et al: The results of chemotherapy for extragonadal germ-cell tumors in the cisplatin era: the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience (1975 to 1982). J Clin Oncol 3:1073, 1985.

Johnson DE, et al: Extragonadal germ cell tumors. Surgery 73:85, 1973.

Kantrowitz AR: Extragenital chorioepithelioma in a male. Am J Pathol 10:531, 1934.

Kay PH, Wells FC, Goldstraw P: A multidisciplinary approach to primary nonseminomatous germ cell tumors of the mediastinum. Ann Thorac Surg 44:578, 1987.

Kersh CR, Hazra TA: Mediastinal germinoma: two cases. Va Med 112:42, 1985.

Knapp RH, et al: Malignant germ cell tumors of the mediastinum. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 89:82, 1985.

Lachman MF, Kim K, Koo BC: Mediastinal teratoma associated with Klinefelter's syndrome. Arch Pathol Lab Med 110:1067, 1986.

Laipply TC, Shipley RA: Extragenital choriocarcinoma in the male. Am J Pathol 21:921, 1945.

Landanyi M, et al: Cytogenetic and immunohistochemical evidence for the germ cell origin of a subset of acute leukemias associated with mediastinal germ cell tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst 82:221, 1990.

Levitt RG, Husband JE, Glazer HS: CT of primary germ-cell tumors of the mediastinum. AJR Am J Roentgenol 142:73, 1984.

Logothetis CJ, et al: Chemotherapy of extragonadal germ cell tumors. J Clin Oncol 3:316, 1985.

Luna MA, Valenzuela-Tamariz J: Germ-cell tumors of the mediastinum, postmortem findings. Am J Clin Pathol 65:450, 1976.

Martini N, et al: Primary mediastinal germ cell tumors. Cancer 33:763, 1974.

McNeil MM, Leong AS, Sage RE: Primary mediastinal embryonal carcinoma in association with Klinefelter's syndrome. Cancer 47:343, 1981.

Meares EM Jr, Briggs EM: Occult seminoma of the testis masquerading as primary extragonadal germinal neoplasms. Cancer 30:300, 1972.

Moran CA, Suster S: Primary germ cell tumors of the mediastinum. I: Analysis of 322 cases with special emphasis on teratomatous lesions and a proposal for histopathologic classification and clinical staging. Cancer 80:681, 1997.

Moriconi WJ, et al: Primary mediastinal germinomas in females: a case report and review of the literature. J Surg Oncol 29:176, 1985.

Motzer RJ, et al: Molecular and cytogenetic studies in the diagnosis of patients with poorly differentiated carcinomas of unknown primary site. J Clin Oncol 13:274, 1995.

Myers TJ, Kessimian N, Schwartz S: Mediastinal germ cell tumor associated with the hemophagocytic syndrome. Ann Intern Med 109:504, 1988.

Nichols CR, et al: Hematologic malignancies associated with primary mediastinal germ cell tumors. Ann Intern Med 102:603, 1985.

Nichols CR, et al: Klinefelter's syndrome associated with mediastinal germ cell neoplasms. J Clin Oncol 5:1290, 1987.

Nichols CR, et al: Hematologic neoplasia associated with primary mediastinal germ cell tumors. An update. N Engl J Med 322:1425, 1990.

Oberman HA, Libcke JH: Malignant germinal neoplasms of the mediastinum. Cancer 17:498, 1964.

Orazi A, et al: Hematopoietic precursor cells within the yolk sac tumor component are the source of secondary hematopoietic malignancies in patients with mediastinal germ cell tumors. Cancer 71:3873, 1993.

Pachter MR, Lattes R: Germinal tumors of the mediastinum. A clinicopathologic study of adult teratomas, teratocarcinomas, choriocarcinomas and seminomas. Chest 45:301, 1964.

Peison B: Embryonal teratocarcinoma of the mediastinum in a woman with foci of anaplastic cells simulating choriocarcinoma. Chest 58:169, 1970.

Polansky SM, Barwick KW, Ravin CE: Primary mediastinal seminoma. AJR 132:17, 1979.

Rather LJ, Gardiner WR, Frericks JB: Regression and maturation of primary testicular tumors with progressive growth of metastases: report of six new cases and review of literature. Stanford Med Bull 12:12, 1954.

Richenstein LJ: Tumors of the central nervous system. Second Series. Fascicle 6. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 1972, p. 270.

Ringertz N, Lidholm SO: Mediastinal tumors and cysts. J Thorac Surg 31:458, 1956.

Rubush JL, et al: Mediastinal tumors: review of 186 cases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 65:216, 1973.

Sabiston DC Jr, Scott HW Jr: Primary neoplasms and cysts of the mediastinum. Ann Surg 136:777, 1952.

Sandhaus L, Strom RL, Mukai K: Primary embryonal-choriocarcinoma of the mediastinum in a woman. A case report with immunohistochemical study. Am J Clin Pathol 75:573, 1981.

Scheike D, Visfeldt J, Petersen B: Male breast cancer. 3. Breast carcinoma in association with the Klinefelter syndrome. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand [A] 81:352, 1973.

Schimke RN, et al: Choriocarcinoma, thyrotoxicosis and the Klinefelter syndrome. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 9:1, 1983.

Schlumberger HG: Teratoma of anterior mediastinum in group of military age: study of 16 cases and review of theories of genesis. Arch Pathol 41:398, 1946.

Sickles EA, Belliveau RF, Wiernik PH: Primary mediastinal choriocarcinoma in the male. Cancer 33:1196, 1974.

Sogge MR, McDonald SD, Cofold PB: The malignant potential of the dysgenetic germ cell in Klinefelter's syndrome. Am J Med 66:515, 1979.

Toner GC, et al: Extragonadal and poor risk nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. Survival and prognostic features. Cancer 67:2049, 1991.

Turner AR, et al: Mediastinal germ cell cancers in Klinefelter's syndrome. Ann Intern Med 94:279, 1981.

Williams SD, et al: Treatment of disseminated germ cell tumors with cisplatin, bleomydin, and either vinblastine or etoposide. N Engl J Med 316: 1435, 1987.

Reading References

Beyer J, et al: High-dose chemotherapy as salvage treatment in germ cell tumors: a multivariate analysis of prognostic variables. J Clin Oncol 14:2638, 1996.

Broun ER, et al: Salvage therapy with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous bone marrow support in the treatment of primary nonseminomatous mediastinal germ cell tumors. Cancer 68:1513, 1991.

Feun LG, et al: Vinblastine (GLB), bleomycin (BLEO), cisdiaminedichloroplatinum (DDP) in disseminated extragonadal germ cell tumors. A Southwest Oncology Group study. Cancer 45:2543, 1980.

Motzer RJ, et al: High-dose carboplatin, etoposide, and cyclophosphamide for patients with refractory germ cell tumors: treatment results and prognostic factors for survival and toxicity. J Clin Oncol 14:1098, 1996.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 203