138 - Esophageal Trauma

Editors: Shields, Thomas W.; LoCicero, Joseph; Ponn, Ronald B.; Rusch, Valerie W.

Title: General Thoracic Surgery, 6th Edition

Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Volume II > The Mediastinum > Section XXVII - Invasive Diagnostic Investigations and Surgical Approaches > Chapter 162 - Sternotomy and Thoracotomy for Mediastinal Disease

Chapter 162

Sternotomy and Thoracotomy for Mediastinal Disease

Joseph LoCicero III

Mediastinoscopy and mediastinotomy are excellent incisions for diagnostic evaluation of the mediastinum. For tumor removal, larger incisions must be used. The two most common incisions for exposure of the mediastinum are median sternotomy and thoracotomy (see also Chapter 25).

STERNAL INCISIONS

Mediastinal exposure for removal of tumors has been used since the nineteenth century. Milton (1897) split the entire sternum in a procedure termed an osteoplastic anterior mediastinotomy. Much later, Julian and co-workers (1957) popularized this incision for cardiac procedures. In the intervening years, Sauerbruch (1929) described the sternal-splitting, manubrium-sparing approach to the mediastinum. Today, the most common anterior approaches to the mediastinum are complete median sternotomy, manubrium splitting, and the sternal-sparing incision. The most common thoracotomy incision for mediastinal exposure is bilateral thoracotomy with sternal transsection (clamshell) incision.

Rationale

Median sternotomy affords the best approach to the anterior compartment and most of the visceral compartment of the mediastinum, with the exception of the esophagus. Tumors of the anterior mediastinum are most effectively removed through this incision.

Thymectomy can be performed through a limited sternotomy. The complete sternotomy is also excellent exposure for various vascular repairs and for tracheal reconstruction on resection. For thymectomy, a small upper sternotomy may be appropriate. It affords a good cosmetic result when the mediastinal disease is benign and localized.

Becoming more popular is the bilateral thoracotomy with division of the sternum transversely to gain access to the mediastinum. This operation has acquired the euphemism clamshell incision. Bains and associates (1994) demonstrated its usefulness for a variety of malignant diseases. This incision is usually done for bulky mediastinal tumors. However, Ris and colleagues (1996) showed its usefulness for mediastinal infections.

Technique for Full Sternotomy

Several variations of full sternotomy are presently in use. Although the sternum is divided in the same manner, the skin incisions vary for special approaches for tumors or for cosmesis.

Skin Incision

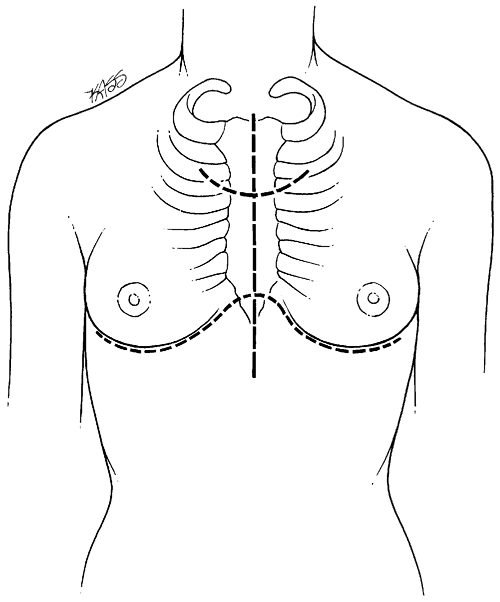

When dividing the sternum, two skin incisions are possible (Fig. 162-1). The most common is the midline incision. This extends from the sternal notch inferiorly to a point just below the xiphoid. Some surgeons make the incision shorter at either or both ends to make the incision more cosmetic. Dissection, usually performed with the electrocautery, is carried through the subcutaneous tissue to the anterior sternal fascia. There is a space between the attachments of the pectoralis major muscles from right and left, leaving a muscle-free approach directly to the outer sternal table. Superiorly, the subcutaneous tissue is swept bluntly away from the sternal notch, exposing the sternal ligament. There is usually a bridging anterior jugular vein, which may be swept bluntly superiorly or divided if necessary. The sternal ligament is a broad-based ligament beginning at the posterior border of the manubrial notch. This is sharply divided to allow a finger to enter the mediastinum posterior to

P.2450

the sternum. Inferiorly, the incision is carried down over the linea alba, which is divided 1 or 2 cm beyond the xiphoid.

|

Fig. 162-1. Possible skin incisions for sternotomy. When a complete sternotomy is to be made, either a long vertical incision or an inframammary incision is used. When only the upper sternum is split, a short collar-type incision may be appropriate. |

An alternative skin incision is the inframammary incision. This approach is almost always reserved for cosmetic purposes but may be necessary for providing the best closure after extensive tumor resection. It may be useful as well if the upper mediastinum has been previously irradiated. The incision is carried in a semicircular fashion underneath both breasts and connected to a semicircular incision over the sternum. Exposure to the sternum requires extensive mobilization bilaterally underneath the breasts. This is performed by extending the subcutaneous incision down to the prepectoral fascia and creating large flaps bilaterally. This is continued until the sternal notch is reached.

|

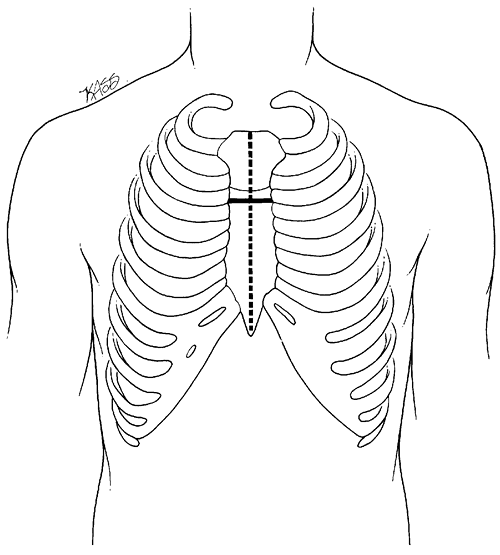

Fig. 162-2. Possible sternotomies. The usual approach is a full vertical sternotomy. A partial upper inverted T incision may be used for thymectomy. The popular alternative is an inframammary incision combined with a transverse sternotomy through the fourth interspace, known as the clamshell incision. |

Sternal Incision

To split the sternum in the midline, the sternal notch and the xiphoid are identified. At the angle of Louis, two straight hemostats are placed next to the sternum to identify the midpoint of the sternum. This is done because the pectoralis muscles do not always delineate the center of the sternum. The anterior table of the sternum is then marked by incising the periosteum with the electrocautery, connecting these three points. The xiphoid is then divided sharply with scissors. An oscillating sternal saw can then be used to divide the sternum from either above or below. This is performed with the lungs deflated (Fig. 162-2).

Closure

When the entire sternum is divided, two chest tubes are used to drain the mediastinum. If the pleura has been entered, one of the chest tubes is placed in that pleural space. If postoperative hemorrhage is anticipated with the pleura open, it may be necessary to place a separate tube thoracostomy in a posterolateral position. The sternum is then reapproximated using interrupted sutures around the sternum. The usual suture used for this is No. 5 or 6 wire. Alternatives to this are No. 6 Mersilene or No. 5 Tycron suture. Both of these materials for closure of the sternum have excellent results. The subcutaneous tissue and fascia may be closed in layers. It is important that the fascia over the sternum be approximated tightly to prevent outside contamination or collection of a coagulum, which may act as a culture medium for bacteria. In the case of inframammary incisions, closed suction drains are placed in the subcutaneous plane, and the subcutaneous tissue and skin are closed in layers.

Technique for Partial Sternotomy

The skin incision for the partial sternotomy approach is a curved incision with the center located at the angle of Louis. The most important part of the incision is the planning phase. A skin flap must be developed from the area of the incision up to and above the sternal notch. The sternum will be divided down to the second interspace. To plan the incision, a large caliper is helpful. A compass, a goniometer, or an obstetric caliper is used to inscribe an arc whose center is located at the cricoid cartilage and whose radius extends to the superior border of the third rib. The incision

P.2451

extends for a distance of 5 cm on either side of the midline. This is usually sufficient to allow development of the superior flap. The length should be appropriate before making the incision because distortion of the incision after the development of the flap makes accurate lengthening difficult.

A thick flap is developed. The incision is carried down through the subcutaneous tissue to the pectoralis and sternal fascia. This thick flap is developed symmetrically cephalad. The flap is widest at its base and extends in a triangular fashion to end in a 2-cm-wide flap, 2 cm above the sternal notch. As in the inframammary incision, a flap of skin and subcutaneous tissue is raised until the sternal notch is reached. The undermining must be extended to the lower flap as well to provide a tension-free cosmetic closure.

Only the upper sternum is divided. The internal thoracic arteries must be exposed bilaterally at the level of the second intercostal space. This is done by incising the pectoralis and exposing the branches of the vessel. By blunt dissection, these incisions are connected through the midline under the sternum. The oscillating sternal saw is then used to divide the sternum at this point. Placing the oscillating sternal saw in the sternal notch, the surgeon divides the sternum in the midline down to this incision. It is almost always necessary to ligate the internal thoracic arteries bilaterally to open this incision for proper exposure of the thymus gland.

Closure

When a partial sternotomy incision is performed, closed suction drains are used for both the mediastinum and subcutaneous tissue. One drain is placed on either side of the sternum, with one going through the intercostal space and into the mediastinum, and the other lying over the sternum. The manubrium is closed as described, with two additional sutures used to anchor the manubrium to the sternum in a criss-crossing X-type pattern. The subcutaneous tissue and skin are then closed.

Sternotomy Complications

Complications of sternal incisions in general are rare and should occur in fewer than 3% of cases. Occasionally, undrained hematomas may be present within the mediastinum. When flaps are created to expose a portion or all of the sternum, seromas may develop under these flaps, especially in patients who are allowed early mobilization of their arms. Mediastinitis and sternal dehiscence or sternal nonunion are rare complications when this incision is used for tumor removal.

THORACOTOMY

Lateral and posterolateral thoracotomy are the most common incisions in general thoracic surgery. In addition to pulmonary resection, thoracotomy exposes the lateral aspect of the mediastinum for biopsy and resection.

Rationale

Thoracotomy is the best approach for esophageal lesions and tumors of the posterior portion of the visceral compartment of the mediastinum and of the paravertebral sulcus. Exposure to the anterior compartment is limited. However, it is important to remember that the accessible structures vary on each side.

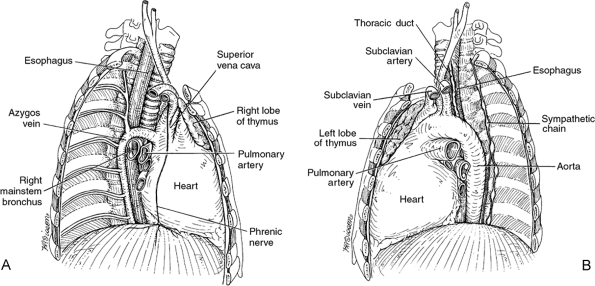

On the right, the structures that are accessible include the esophagus, superior vena cava, right phrenic nerve, thoracic duct, trachea, and right paratracheal nodal chain (Fig. 162-3A). The tracheal carina and proximal portion of the left main-stem bronchus can be adequately exposed through this approach.

On the left, the aorta, superior and inferior portions of the thoracic duct, left phrenic nerve, and lower one-third of the esophagus are accessible (Fig. 162-3B). Only a small portion of the trachea can be exposed from this side.

Technique

With the exception of operations on the lower one-third of the esophagus, a high lateral thoracotomy is the usual best approach to the mediastinum. Occasionally, for high mediastinal lesions, an axillary thoracotomy is most useful.

For the lateral thoracotomy, an incision is made just below the tip of the scapula. Bethencourt and Holmes (1988) and Kittle (1988) suggested that one should make efforts to spare the latissimus and the serratus muscles. This is done by mobilizing the muscles both superiorly and inferiorly and retracting them away from the intercostal space to be entered. Subsequent investigators have not shown a definitive advantage to muscle-sparing incisions. The fourth intercostal space is the usual entry point for exposure to the mediastinum. If higher exposure is necessary, then an axillary thoracotomy is usually chosen.

For an axillary thoracotomy, the patient is in the lateral thoracotomy position and the arm is retracted at 90 degrees out from the midline. This delineates both the pectoralis and the latissimus muscles. The incision is made between these two muscles and carried down through the subcutaneous tissue to the second or the third intercostal space. Care must be taken to avoid injury to the long thoracic nerve. Once the muscles are dissected and retracted from the area of the incision, the intercostal space may be entered.

Closure

At the completion of the procedure, both anterior and posterior chest tubes are usually placed. The ribs are

P.2452

reapproximated using pericostal sutures, and the subcutaneous tissue and skin are closed in layers.

|

Fig. 162-3. Thoracotomy exposure of the mediastinum. A. The esophagus, superior vena cava, trachea, phrenic nerve, and sympathetic chain are shown on the right. B. The distal esophagus, phrenic nerve, subclavian artery, thoracic duct, and sympathetic chain are shown on the left. |

Complications

The most common complication after a thoracotomy is bleeding. This usually comes from uncontrolled bleeding within the area of mediastinal resection. No firm guidelines for reexploration have been established. However, more than 250 mL per hour for 4 hours is the usual criterion for reexploration.

When performing muscle-sparing incisions, large subcutaneous pockets are created. Extensive mobilization may lead to seroma formation. These are usually self-limited but may be aspirated for patient comfort.

Infections in thoracotomy incisions are rare and should occur in fewer than 1% of all thoracotomies. Because resectional therapy of the mediastinum is usually performed for indications other than infection, contamination of the thoracotomy wound should be less than for other indications. If an infection does occur, it is usually because of a break in surgical technique and the organism is almost always Staphylococcus aureus.

REFERENCES

Bains MS, et al: The clamshell incision: an improved approach to bilateral pulmonary and mediastinal tumor. Ann Thorac Surg 58:30, 1994.

Bethencourt DM, Holmes EC: Muscle sparing posterolateral thoracotomy. Ann Thorac Surg 45:337, 1988.

Julian OC, et al: The median sternal incision in intracardiac surgery with extracorporeal circulation: a general evaluation of its use in heart surgery. Surgery 42:753, 1957.

Kittle CF: Which way is in? The thoracotomy incision [Editorial]. Ann Thorac Surg 45:234, 1988.

Milton H: Mediastinal surgery. Lancet 1:872, 1897.

Ris HB, et al: Descending necrotizing mediastinitis: surgical treatment via clamshell approach. Ann Thorac Surg 62:1650, 1996.

Sauerbruch F: Die Rontgendiagnostik der Intrathorakalen Tumoren und Ihre Differential Diagnose. Berlin: Springer, 1929.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 203