Learning About Culture

Your most vexing business problems likely will have a cultural dimension. In some cases, you will find that aspects of the existing culture are key impediments to realizing high performance. You will thus have to struggle to change them. Other aspects of the culture will turn out to be functional and thus worthy of preservation. Having realized how proud and motivated the workforce was, Chris Bagley could draw on this energy to upgrade the plant. Think how much more difficult it would have been had he inherited a group of complacent, hostile people.

Because cultural habits and norms operate powerfully to reinforce the status quo, it is vital to diagnose problems in the existing culture and to figure out how to begin to address them. These assessments are particularly important if you are coming in from the outside or joining a unit within your existing organization that has a strong subculture.

You can t hope to change your organization s work culture if you don t understand it. One useful framework for analyzing an organization s work culture approaches it at three levels: symbols, norms, and assumptions. [1]

-

Symbols are signs, including logos and styles of dress; they distinguish one culture from another and promote solidarity. Are there distinctive symbols that signify your unit and help members recognize one another?

-

Norms are shared social rules that guide right behavior. What behaviors get encouraged or rewarded in your unit? What elicits scorn or disapproval?

-

Assumptions are the often-unarticulated beliefs that pervade and underpin social systems. These beliefs are the air that everyone breathes. What truths does everyone take for granted?

To understand a culture, you must peer below the surface of symbols and norms and get at underlying assumptions. To do this you need to carefully watch the way people interact with one another. For instance, do people seem most concerned with individual accomplishment and reward, or are they more focused on group accomplishment? Does the group seem more casual, or more formal? More aggressive and hard-driving, or more laid-back?

As my colleague Geri Augusto has noted, the most relevant assumptions for new leaders involve power and value . [2] Regarding power, key questions are as follows : Who do key people in your organization think can legitimately exercise authority and make decisions? What does it take to earn your stripes ? Regarding value, what actions are believed by employees to create (and destroy) value? At White Goods, employees were proud of producing premium-quality products, so a decision to move downmarket could easily trigger resistance. Divergent assumptions about power and value ”for example, between workers and managers ”can complicate efforts to align the organization. Some degree of divergence is, of course, unavoidable. The danger comes when the gap becomes too wide to be bridged by effective communication and negotiation.

Organizational, Professional, and Geographic Perspectives

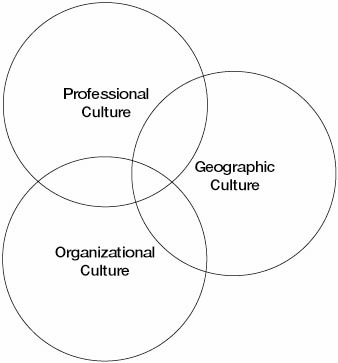

You can also think about culture from three perspectives: organizational, professional, and geographic. As you read the following descriptions, imagine examining each aspect of culture through a camera s zoom lens. Start by zooming in to see organizational culture, then gradually widen your focus to see professional culture, and then focus broadly on geographic culture.

Organizational Culture. Cultures within organizations or groups develop over time, and can be deeply rooted. Organizational culture is expressed in the way people treat one another (friendly, formal, relaxed ), the values they share (honesty, competitiveness , hard work), the routines they follow as they hold meetings and exchange information, and so on.

Organizational cultures vary within and across industries. For example, managers in an established, traditional consumer products company may be comfortable with more elaborate processes and systems than managers in a start-up in the same industry. An energy industry executive might feel he s on shaky ground working in a fashion retail company.

Professional Culture. Managers as a group also share cultural characteristics that distinguish them from other professional groups such as engineers , administrative assistants, and doctors or teachers . But this doesn t mean all managers are alike. In fact, you ve probably seen huge cultural differences within and between business functions.

For example, financial managers have different worldviews than marketing or R&D managers. In part, this is because the people who gravitate toward these functions have different professional training.

Geographic Culture. Geographic changes can present the greatest diversity in culture. The way people do business in different regions of a country can vary significantly. Differences in business cultures between two countries are even more pronounced. For example, U.S. managers tend to work within a more individualistic culture, whereas Japanese managers stress more collectivist values and behaviors.

Moving into New Cultures

If you re moving to a new company within the same industry, or to a new industry (from financial services to food management, for example), you ll likely confront organizational cultural changes.

Your new position may take you to a different functional arena (for example, from operations to marketing) or to a whole new level of responsibility (for instance, from a functional area to general management). In such cases, you will face professional cultural changes ”differences that are significant even when you move to a new position within the same organization.

If you re taking a position with a division in your company that is located in a different city or region in your country, or in another country, you ll likely face geographic cultural changes.

These different kinds of culture change can overlap and reinforce one another (see figure 2-2). For instance, if you move to a new company that s also in a new city or region, you ll face organizational and geographic culture changes. It is useful to assess your culture adaptation challenge on a scale of 1 to 10 on each of these three dimensions. On the organizational culture dimension, a 10 would be a move from a highly centralized, process-focused organization to a highly decentralized, relationship-focused organization. On the professional culture dimension, a 10 would be a move from finance to human resources or vice versa. Finally, on the geographic dimension, a 10 would be a move from Minneapolis to Tokyo. If the total of these three numbers is 15 or greater, then you are facing a major cultural shift. To avoid missteps, you must devote significant energy to understanding and adapting to the new culture or cultures.

Figure 2-2: Intersecting Dimensions of Culture

Adaptation or Alteration?

After identifying the organizational culture to which you re moving, you need to decide whether to adapt to or alter that culture. Whatever your situation, you ll need to understand the impact of existing cultural characteristics on your new situation. In particular, you ll want to assess which cultural characteristics are helping performance, and which may be harming performance. Your future success depends on knowing the difference ”and taking the proper action.

[1] For an informative exploration of organizational culture and the role of leaders in shaping it, see Edgar Schein, Organizational Culture and Leadership, 2d ed. (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1992).

[2] Geri Augusto, unpublished presentations to executive programs at the Kennedy School of Government and the Harvard Business School, Boston, MA.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 105