Selecting and Preparing a Project Team

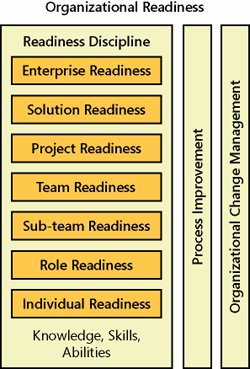

| The goal of selecting and preparing a project team is to deliver the right resources, against the right projects, at the right time. To achieve this, a project should be carefully staffed with team members ready to contribute at the needed skill levels for the given roles. This does not happen magically, it takes careful preparing and continual adjusting. Staffing a project team should be a fluidic process of adding and removing people as needed throughout the life cycle. It typically involves gradually adding appropriately skilled people as a project gets defined; making personnel changes as different skills and abilities are needed over the course of the various tracks; and rolling off team members as they complete their planned work. Typically, a team starts with a few key individuals as the core team. A few senior staff are added to help plan out a solution. These folks often continue as team leads of the various subteams. Additional staff are usually brought on to help develop a solution and are phased off a project typically when there is a high degree of confidence that a solution works and it is subsequently a matter of refining a solution (e.g., typically after the first full functional test in stabilization). By the end of stabilization, a team is typically backed down to the core people plus a deployment team. Some of the people who help develop a solution transition over to other projects to handle subsequent releases/versions of a solution whereas some transition to Operations to help support the deployed solution. Selecting who to bring on a project and when is based on many tangible as well as subjective factors. The tangible factors include budgetary constraints (we all wish we could afford a whole team of the best and brightest); matching needed skills and proficiencies with available personnel; an organization's desire to provide mentoring or on-the-job training necessitating a mix of senior and junior skilled personnel; and technology complexity. Subjective factors include team cohesiveness, team chemistry, resultant team readiness, development style (e.g., best suited for efforts that are more formal), and leadership. For the staffing process to be fluidic, a team needs to adopt a means to easily ramp-up and transition personnel onto a project as well as capture lessons learned and collateral from personnel rolling off a project. To do this, a team and each successive subteam need to decide what is the right level of planning and documentation necessary to ensure smooth transitions. Too little transitional material likely means the new personnel will lose time because of a slow start. Too much transitional material likely means the overall project will suffer under the burden of updating and managing this material. Keep in mind that the optimal mix often changes as the teams evolve. Another intertwined aspect of preparing a project team is assessing their readiness to perform their given tasks, both current and future, as well as their ability to adapt to the changing project environment. The next section discusses a means, called the MSF Readiness Management Discipline, to fine-tune individual readiness up through readiness at the enterprise level. MSF Readiness Management DisciplineAn organization can expend great effort readying a team. Readiness has two components: technical readiness and psychological readiness (e.g., willingness and mental preparedness). As defined within MSF, technical readiness is a measurement of the current state versus the desired state of knowledge, skills, and abilities of individuals and teams within an organization. This measurement is the real or perceived capabilities at any point during the ongoing process of planning, building, and managing solutions. The MSF Readiness Management Discipline, a core component of MSF, addresses technical readiness. It provides guidance and processes in the areas of assessing and acquiring knowledge, skills, and abilities necessary for solution delivery. It is based on MSF foundational principles and provides guidance for a proactive approach to readiness throughout a solutions life cycle. Together with proven practices, this discipline provides a foundation for individuals, their project teams, and up to the enterprise level to manage readiness, as depicted in Figure 7-3. The additional organizational readiness examples shown in the figure (i.e., process improvement and organizational change management) should be proactively addressed but are outside the focus of this discipline. Figure 7-3. MSF Readiness Management Discipline related to organizational readiness As shown in this figure, there are many levels of readiness to consider. Each level builds off anotherstarting with individual readiness that focuses on knowledge, skills, and abilities needed to meet the responsibilities required for each role. As each successive level is traversed, readiness evolves into making sure an organization is poised for strategic initiatives and successful adoption and realization of its technology investments. Given this additive nature, organizations should start by first focusing on addressing individual readiness to assess and affect change to readiness. The foundational principles, mindsets, and proven practices of MSF as applied to the MSF Readiness Management Discipline are outlined in the following sections. The primary ideals of effective readiness management are highlighted in this section and are referenced throughout this book. Foundational Principles Applied to ReadinessThe MSF foundational principles are cornerstones of the framework's approach. Those principles relating to successful readiness management are highlighted in this section. Foster Open CommunicationsBy establishing an open learning environment that encourages individuals to take ownership of their skills development, acknowledge and commit to rectifying skill deficiencies, and participate in setting their goals for their learning plans, individuals tend to take greater pride and have a higher drive to succeed and help others. Groups successful in creating this type of open learning environment often have periodic team training sessions where knowledge and learning are both shared and received. Work Toward a Shared VisionAn understanding of individual team member readiness enables a shared vision to be framed in a context such that every team member grasps what is envisioned for a solution. It also allows for a more realistic understanding of what a team is able to accomplishenabling a more realistic vision and matching expectations. Empower Team MembersWhen team members have requisite skills, they are better able to perform their role. As such, they feel more empowered to contribute successfully to delivering a solution. This feeling often leads to higher productivity and creativity as well as team harmony. Typically, if an organization has a good understanding of skills readiness and how it directly benefits an organization, an organization is more willing to provide additional training and skills enhancement activities. Establish Clear Accountability, Shared ResponsibilitySimilar to the benefits of empowering team members, better alignment of team member proficiency and role competency usually leads to more accountability (i.e., it is easier to be accountable when you know what you are doing). Good alignment usually also leads to a high degree of confidence across a team. As such, team members are typically more willing to be jointly responsible for a solution. Deliver Incremental ValueWith readiness gaps identified and actively being minimized, team members are able to focus on delivering business value instead of fretting about role mismatches. With role alignment, team members are well suited to understand what needs to be delivered for customers to realize value. Frequent deliveries mean that smaller portions of a solution are being delivered more often. This provides more learning opportunities for a team to increase their skills. It also helps team leads quickly calibrate team member skills and abilities as well as role and task skill assumptions, and if necessary, make staffing changes early on in the life cycle. Stay Agile, Expect and Adapt to ChangeChanges in project direction, operational procedures, or individual resources do occur unexpectedly and with significant impact. Being adept at successfully facing change means having individuals and project teams committed to readiness. Readiness agility refers to having a defined readiness management process, doing proactive readiness management, and providing incentives that encourage individuals and project teams to gain the appropriate level of knowledge, skills, and abilities swiftly through training, mentoring, or hands-on learning to successfully meet their defined goals. Leaving out any of these aspects of the Readiness Management Discipline increases the likelihood of risks and failure. Without the agility achieved from having a readiness management process in place and quickly being able to obtain the appropriate skills necessary for success, organizations sometimes miss opportunities and find themselves behind their competition. Invest in QualityObtaining the appropriate skills for a project team is an investment. Because they take time out of otherwise productive work hours, the funds for classroom training, courseware, mentors, or consulting can certainly be a significant monetary investment. However, investing time and resources to obtain or develop the right people with the right skills generally results in higher quality output and greater chances of success. Projects that fail do not supply a positive return on investment. Projects that succeed with low quality result in lowered satisfaction and adoption, which in turn might have significant cost impact in areas such as support. Up-front investment in staffing teams with the right skills generally leads to greater success and higher quality. Learn from All ExperiencesCapturing and sharing both technical and nontechnical best practices are fundamental to ongoing improvement and continuing success by ensuring the following:

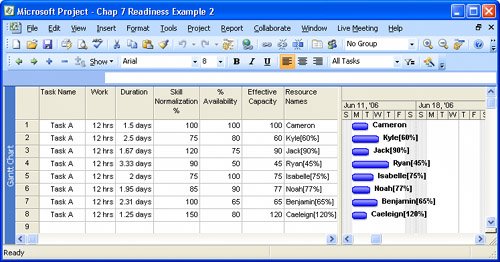

Checkpoint reviews help teams to make midcourse correction and avoid repeating mistakes. Additionally, capturing and sharing this learning creates best practices out of the experiences that went well. Partner with CustomersPartnering with customers is a mutually beneficial means to improve team readiness and validate customer readiness to use a solution. It is great way to engage customers in their environment. A team should use this opportunity to better understand how customers use their current solutions and how they might use a solution being developed. While engaging customers, a team might use this opportunity to calibrate their assumptions about customer readiness. A team can also use this to informally validate alternative solution implementation approaches and options. MSF Readiness Management FundamentalsIn this section, important concepts about readiness that are central to understanding the MSF Readiness Management Discipline are discussed. Understand the Experience Within Each Team MemberIndividual knowledge and experience are assets that offer dual value. The individual who possesses the knowledge and experience benefits personally, and the organization as a whole benefits when the individual applies knowledge and experience to projects. The value of this knowledge is diminished for both an individual and an organization without a collective understanding and measurement. For example, an individual might possess knowledge that an organization does not currently recognize, or an organization can lack a method to access that knowledge. Consequently, knowledge assessment and knowledge management are key concepts of a readiness effort. An organization should promote readiness through the capture and utilization of knowledge. A defined knowledge management program takes the idea from concept to reality. The benefit of a knowledge management program is its identification of knowledge lacking in both individuals and an organization. Readiness Must Be Continuously ManagedLearning must be made an explicit and planned activityfor example, by dedicating time for it in the schedulebefore it will have the desired effect. Carry Out Readiness PlanningAs with any aspect of a project, planning for readiness is the key to success. Knowing up front the required level of readiness creates a proactive approach to assembling the appropriate resources, defining budgetary needs for training or obtaining the appropriate expertise, and building training time into the schedule. Readiness plans for each role are rolled up to create an overall readiness plan for a project team. Without planning, readiness management is likely to be overlooked until a significant gap in skills causes a project to be challenged, leading to significant risk of failure. Measure and Track Skills and GoalsSuccessful readiness management includes assessing and tracking skills and the goals of individuals. This includes taking into account current abilities versus the desired knowledge levels so that the appropriate matching of skills can happen at both individual and project levels during resource allocation. Tracking and measuring the information help ensure project teams have the capability of doing readiness planning. Through the process of planning, project teams select members with both the desire to participate and skills required. The most effective way to accomplish this is by using a mandatory skills-reporting database and requiring all individuals to keep the data up to date. Treat Readiness Gaps as RisksAfter completing assessments and determining proficiency gapsessentially finding the current versus desired stateproject teams should identify readiness gaps as risks and treat them as such. Gaps in areas of key knowledge, such as the skills and abilities needed to complete a project successfully, can have profound effects on the schedule, budget, and resources needed to fill those gaps. Depending on the type of project, readiness risks can delay project initiation or indicate a need to obtain resources with the appropriate skills. When gaps are treated as risks, there is generally a more proactive approach to readiness management and subsequent mitigation of these risks. Avoid Single Points of Failure in Skills CoverageIt is not good to have single points of failure, including team skills. Therefore, a team should have a primary and secondary for every skill set deemed important to the success of a project. Readiness and the MSF Team and Governance ModelsAs the size and complexity of solutions tend to become greater, so does the importance of establishing and maintaining proactive readiness activities throughout a solution life cycle. Readiness goals should be expressed as activities and deliverables produced throughout a project life cycle intended to achieve those goals. Each advocacy group performs activities and produces deliverables that relate to project readiness goals for their constituency. When readiness is seen as a component of project goals, readiness deliverables are completed at various levels within each track and checkpoint of a project. Thus, mapping of readiness activities and deliverables to the MSF Governance Model tracks is useful, but teams will need to adjust their activities (and when these activities occur) according to the size and type of project. The focus is on preparing a team with the knowledge, skills, and abilities to deliver a project effectively. In the early stages of the MSF Envision Track, this includes documenting a project approach to readiness. This approach documentation might contain information such as follows:

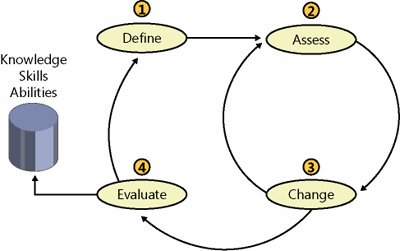

During the MSF Plan Track, the high-level activities and deliverables identified during envisioning are taken to a greater level of detail, with estimates and dependencies applied for the tasks and integrated into the overall project plan and schedule. This helps determine the true cost and feasibility of a project beyond a development effort alone. This is the time when team assessment should be conducted to produce information on skills gaps so analysis and planning for bridging that gap move forward. Because the needs of a team precede operational needs, many of the gaps identified for a team are filled during planning. This improves a design and determines readiness of a team for development. Effectively prepared, Development and Test teams focus on project deliverables during a Build Track. Release/Operations, User Experience, and Product Management often begin to be involved in the early stages of preparation for final release. Incremental exposure of a solution to external constituencies and gradual involvement in later stages of testing enable a team to assess efficacy of organizational readiness activities of the eventual solution owners. In the last stages of a project, most of the readiness activities have been or are being executed as the training and preparation of users and support and operations staff are done, and a solution is released and/or deployed. At the end of a project, team effort relative to readiness is evaluated by a team and an organization so that subsequent projects are able to repeat successes and learn from areas that require improvement. Deliberate outputs for readiness are often embedded in regular checkpoint deliverables but can be itemized separately to highlight or manage them with individual attention. If large readiness gaps exist, Program Management needs to make sure readiness activities and deliverables are not relegated to the background or assumed to occur indirectly. Readiness activities are people-centric, and therefore require constant vigilance. MSF Readiness Management ProcessLead Advocacy Group: Program Management The MSF Readiness Management Discipline includes a readiness management process to help prepare for the knowledge, skills, and abilities needed to build and manage projects and solutions. It is considered a systematic, ongoing, iterative approach to readiness and is adaptable to both large and small projects. The MSF Readiness Management Process, graphically depicted in Figure 7-4, is composed of four steps:

Figure 7-4. Steps of the MSF Readiness Management Process The most basic approach is simply to assess skills and make appropriate changes through training and assessment. On projects that are small or have short time frames, this streamlined approach is quite effective. However, performing the steps of defining needed skills, evaluating the results of change, and keeping track of knowledge, skills, and abilities allows for the full realization of readiness management. It is also typically where organizations reap rewards from investments in readiness activities. Step 1: DefineDuring envisioning, a team aligns its business and technology goals to create a shared vision of what a solution will look like. A team uses this to define environmental factors under which the team needs to perform (i.e., called scenarios). An example of a scenario is a high-risk infrastructure effort with tight deadlines. Using this information, a team defines a set of skills (i.e., competencies) needed in the various advocacy groups to achieve that vision successfully. The collective set of skills defined for each advocacy group can be further decomposed into required skill sets for each functional area. Scenarios are also used when assessing team member abilities (i.e., proficiencies). All of this is encompassed in the first step of the MSF Readiness Management Process called Define. As just explained, the three components of defining readiness include the following:

Outputs from this step include the following:

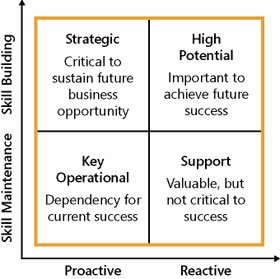

ScenariosSkill proficiency is greatly influenced by a solution delivery environment. A person with a given ability to perform a task will have varying degrees of success given different environmental factors. For example, some people are not fazed by a work environment with uncertainty and ever-changing requirements. Conversely, others lose productivity in this type of environment. Therefore, a person with an aversion to change put in a changing environment will not do as well as if that person were put in an environment with little change. This exemplifies how the same person with the same skills might exhibit different amounts of productivity because of environmental factors. The description and classification of the different types of environments and situations in which teams operate within an organization are called scenarios. Scenarios generally fall into one of four categories as shown here and in Figure 7-5:

Figure 7-5. Typical scenario categories for solution delivery[1]

By categorizing projects within an organization into appropriate scenarios, readiness planning is done according to the unique nature of that project. Different scenarios require distinct approaches to obtaining the appropriate resources and skills for that project type. By first defining the scenario best classifying a project, the appropriate competencies and proficiencies can then be mapped. Differing scenario types can also drive decisions for outsourcing or using consulting to obtain the skills needed. For example, staffing for a high-potential project scenario might include specialized vendor-trained consultants versus a project scenario where readiness planning typically includes courseware training and certification of in-house staff. Following are a few approaches to obtain the appropriate levels of readiness for each scenario in terms of knowledge, skills, and abilities.

With projects and their associated scenarios defined, it is then time to identify the competencies and subsequent proficiencies associated with these project scenarios. CompetenciesCompetencies define a level of adeptness with which teams are able to perform given tasks given a particular scenario. Being adept means having the requisite knowledge and skills to perform the given role and associated tasks at an expected proficient level of performance (i.e., needed ability to perform a task). Competencies are commonly associated with task types or roles. A skills profile is associated with each task type or role such that an individual with the requisite skills should be able to perform. With roles, it is expected that competency in a few different areas is required. For example, on a particular project, the Infrastructure Architect role requires expertise in designing solutions that involve the Microsoft Active Directory and Exchange Server product lines. ProficienciesProficiency is a measure of an individual's ability to execute tasks or demonstrate skill or capability within a given scenario. To make sure the difference between competencies and proficiencies is clear, consider that proficiencies are an assessment of a team member's abilities to perform in various capacities in various scenarios, whereas competencies define the abilities necessary to be able to perform a respective task type or role in a specific scenario. The proficiency is designated by the level at which individuals are assessed or assess themselves. A proficiency level provides a benchmark, or starting point, for analyzing the gap between the individuals' current skills set and the necessary skills for completion of the tasks associated with the given scenario. During the Define step of the MSF Readiness Management Process, the level at which individuals should be performing for each role in given scenarios is determined using either self-assessment or assessment testing. Individual proficiency levels are then associated with required project competencies so that when assessments are completed, the output is measured and analyzed to determine proficiency gaps. A proficiency gap is when performance is at a lower level than that of the expected proficiency level for a role or task type. Table 7-2 shows a sample proficiency rating scale used in proficiency assessments.

Step 2: AssessThe Assess step of the MSF Readiness Management Process measures individual proficiencies, and identifies and plans to mitigate readiness gaps. Two types of readiness gaps are assessed:

By measuring these readiness gaps, learning plans are assembled to start to minimize these gaps. Activities during this step include the following:

Outputs from this step are as follows:

Measure Individual Knowledge, Skills, and AbilitiesTwo options are available for performing individual assessments: self-assessment and standardized tests. Self-assessment is a procedure whereby individuals assess their own level of ability. This includes responding to a list of questions such as: "How well are you able to perform x?" Self-assessment requires individuals to measure their own abilities using a scale such as that shown in Table 7-2. This technique is effective in learning how individuals perceive their own levels of ability. Although it might not always be an accurate assessment of the individual's abilities, it is a quick way to get some measurements. In addition, it helps later in forming personalized learning plans to know where individuals think they are with their abilities. Standardized testing is the other method of assessing an individual's abilities. It enables calibration of an individual's skills as compared to a given baseline. This type of test requires individuals to respond to specific, often technical, questions to show their knowledge; to perform specific tasks; and to demonstrate analytical abilities. Revisit Readiness NeedsTeams are assembled based on an estimated level of competency needed for the various roles. As teams gain experience with delivering, each team should revisit their readiness needs. In addition, readiness needs should be regularly revisited corresponding with changes in the business environment and changes in technology. Although it is expected that project readiness needs will flux over the course of a solution delivery life cycle, if the variance is big enough, this should be treated as a readiness gap (if the need increases) or a potential staffing change (if the need decreases). Identify and Analyze Readiness GapsA readiness gap is when an individual has demonstrated lower proficiency for a specific, required competency than the defined required level for his or her role (identified during the Define step). As mentioned previously, individual readiness gaps roll up through the various levels and can lead to a readiness gap at the enterprise level. Usually, this is not the case because part of the staffing process would make sure that selected team members complement each other's proficiencies and competencies so as to not have readiness gaps. However, in many cases when facing a new project, organizations do not have the internal capabilities or experience to assess correctly the skills and abilities needed. Providers such as Microsoft Certified Technical Education Centers (CTEC) or consulting organizations are able to assist with this essential step. Create Learning PlansOnce readiness gaps at all levels have been analyzed, the information gathered is used to formulate learning plans. A learning plan consists of both formal and informal learning activities and guides individuals through the process of moving from one proficiency level to the next. A learning plan must go beyond traditional training delivery, such as instructor-led and self-study, and account for how to begin to apply the learned information to the job. This is usually reinforced with on-the-job mentoring or coaching. An effective learning plan takes into account the following:

It is critical that an organization and project team support its members as they execute their learning plans. Identifying a readiness gap is meaningless unless an organization is ready to mitigate it. Step 3: ChangeThe Change step of the MSF Readiness Management Process implements the learning plans in an attempt to minimize readiness gaps and tracks progress to make sure the efforts are effective. As just identified, activities during this step include the following:

Outputs from this step include the following:

Implement Learning PlansActivities and tasks outlined in an individual's learning plan should be incorporated into that person's respective project schedule. Otherwise, these activities and tasks are at great risk of being overwhelmed by the other planned activity. Track ProgressIt is important not just to facilitate learning but also to understand the effectiveness of the readiness efforts. Because learning is more involved and subjective than training is, it is challenging to track progress against the learning plans. The approach to track progress does not have to be complex. It might be as simple as having the individual report completed training. Step 4: EvaluateThe Evaluate step of the MSF Readiness Management Process determines whether the learning plans were effective and whether lessons learned are being successfully implemented. During evaluation, a determination is made if the desired state, as described during the Define step and measured during the Assess step, was achieved during the Change step. In addition, a team should harvest lessons learned to help make the next project more successful. This Evaluate step could be the end of the process. But because learning is an ongoing need for continued success, evaluation should be viewed as input to the next iterative cycle through the process. Activities during this step include the following:

Outputs from this step include the following:

Review ResultsA real-world test of learning activities success is the effectiveness of the individual back on the job. A benefit of reviewing the results with each individual is the capability not only to guide individuals through their first exposure to new concepts, but also to enable the expert (mentor or coach) to assess training effectiveness. Using verbal and written feedback, the expert highlights the areas where individuals are performing well and are demonstrating understanding of the given concepts. Likewise, the mentor or coach is able to provide feedback on the areas where individuals are struggling or appear weak in their understanding and application of the new learning. This review helps to identify whether the knowledge transfer approach taken was the most effective and those areas that might need to be readdressed and where further training might be necessary. This also enables an organization, at any time in the life cycle, to analyze overall readiness to make necessary adjustments to readiness plans. The individuals' activities in this step can include some introspection and self-assessment to determine whether the learning was effective before putting those new competencies to work. Individuals might also decide it is a good time to become certified because they have done the learning, performed the key tasks, and assimilated the knowledge. Manage KnowledgeA natural side effect of training individuals is that the knowledge they acquire becomes intellectual capital that the individual is able to capture and disseminate throughout an organization. As learning plans are completed and applied on the job, individuals discover key learning that their training provided. Sharing this information with others throughout an organization enhances the collective knowledge and fosters a learning community. One objective of the Readiness Management Discipline is to encourage development of a knowledge management system to better enable the sharing and transfer of proven practices and lessons learned, as well as to create a skills baseline of the knowledge contained within an organization. Individuals in an organization carry with them a body of learning, expertise, and knowledge that, however extensive or expansive, encompasses less than the collective knowledge of all the people. A knowledge management system provides an infrastructure by which that knowledge is harnessed and made available to a community. As organizations face the need for global knowledge that needs to be easily and quickly used, compounded by shorter time frames for implementing solutions, requirements increase for individuals to share their knowledge and expertise and to reuse what others have learned. Knowledge management systems provide many benefits, including, but not limited to, the following:

Project Structure Document (Deliverable)Lead Advocacy Group: Program Management A project structure document is the culmination of many Envision Track activities. It reflects roles with needed skills and abilities as identified by readiness management efforts. It reflects feature and function teams needed to deliver a solution. It reflects stakeholder analysis, making sure the team model advocates for each key stakeholder. Overall, it defines the approach a team will take in organizing and managing a project team. |

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 137

- Article 356 Liquidtight Flexible Nonmetallic Conduit Type LFNC

- Article 440: Air Conditioning and Refrigerating Equipment

- Annex D. Examples

- Example No. D2(c) Optional Calculation for One-Family Dwelling with Heat Pump(Single-Phase, 240/120-Volt Service) (See 220.82)

- Example No. D9 Feeder Ampacity Determination for Generator Field Control