DILEMMAS OF FRANCHISING

Franchising that seeks to minimize risks and optimize profits is faced with a number of tensions that need to be reconciled. Again we can see the importance of the global versus local brand image, control versus independency, and, finally, focused versus broad brands.

Franchising Dilemma 1: Global versus Local Brand Image

For many franchisers, the solution has long been obvious: just fade into the landscape. KFC is as good an illustration as one can find. In Japan it sells tempura crispy strips , in Northern England it stresses gravy and potatoes, in Thailand it offers fresh rice with soy or sweet chilli sauce, in Holland it makes a potato and onion croquette, in France it sells pastries alongside the chicken, and in China the chicken gets spicier the further inland you travel.

McDonald's also continues to adapt. There is a meat-free McNistisima menu for the fasting Greek Orthodox in Cyprus, a McRye burger in Finland, a McNifirca burger in Argentina, a kosher McDonald's in Israel, and a McKroket in the Netherlands. Consider the latest fast-food sensation in Kuwait City: the McArabia, an "Islamized" product on Arabic flat bread and served in a restaurant described by the local marketing director, without a trace of irony, as "the mother of all stores."

| |

"I like my pizza when it is hot," declared Dr Hashem H. Al-Refaei, one of our Arab PhD students at THT.

A western Pizza Hut manager thought that this could (only) mean that he liked it either when it was just out of the oven or when it was spicy. But a Pizza Hut manager from the UAE understood the subtlety of localized meaning. Hashem had meant "I like a pizza when the weather is hot."

| |

This localized adjustment to a menu is a visible manifestation of a more profound strategy: "multi-localism" - what we might call "democratizing globalization," so that people everywhere feel some stake in how it impacts on their lives. Has McDonald's packaged itself to be a "multi-local" company by insisting on a high degree of local ownership, or is it just a dictat from HQ insisting on local menus ? Poland has emerged as one of the largest regional suppliers of meat, potatoes, and bread for McDonald's in central Europe. The company is gradually moving from local sourcing of its raw materials to regional and now to global sourcing; every sesame seed on every McDonald's bun in the world comes from Mexico. Friedman asserts that "people will only take so much of 'globalization,' to the extent that companies with a US origin will only be successful through being multi-local, by integrating around the globe economically, without people feeling that they are being culturally assaulted" (Friedman, 2000).

The Friedman thesis ("No two countries that both have a McDonald's have ever fought a war against each other") is obviously no longer technically accurate, but the underlying construct still deserves attention. What Friedman fails to recognize is that globalization does not have to be an all-or-nothing proposition. Let's not forget the economic and social benefits that franchising can offer countries: much needed foreign investment, products that are in demand, entrepreneurial opportunities, the combination of local and regional sourcing, and the culture of customer service and reliable operations, which indigenous operations will surely emulate.

The point is that the franchise system has become far more than just a familiar brand name in these countries; its effects extend well beyond those enjoyed by franchisees and their customers. But being a local brand everywhere is not enough. Information needs to feed back into the main centralized system to generate a truly transnational approach.

Lets see how McDonald's has reconciled this first basic dilemma of franchising its core brand.

Reconciling Centralized Commonalities with Local, Decentralized Variations

This dilemma that McDonald's demonstrates so clearly is the increasing variance in local tastes and supplies , especially in economies recently rocked by currency crises and economic turbulence. Not only is food flavored differently in different places but supplies can also fluctuate in price, so that substituting domestic rice for imported potatoes is not just preferred by customers but may also be cheaper.

As McDonald's brands expand internationally it becomes increasingly important for indigenous managers to make decisions based on local knowledge. It may be a relatively "small" matter, like adding garlic or soy sauce, but this makes all the difference in satisfying local palates and would be difficult, if not impossible , to identify or dictate from HQ. McDonald's may also mean different things in different lands; a quick, family meal for travelers on a US interstate, an unusual guarantee of quality in Moscow, the cheapest source of protein in Cairo, the least expensive air-conditioned restaurant in Dubai, etc.

Those in the field know things that HQ in Chicago cannot, unless it is well informed - and even then such feedback may lose the subtlety of localized meaning. There is no way that McDonald's HQ can know everything about local tastes in every one of its foreign outlets. Such information is not "hard" but "soft." It's something local managers know because they live in the country and it is largely a question of subjectivity .

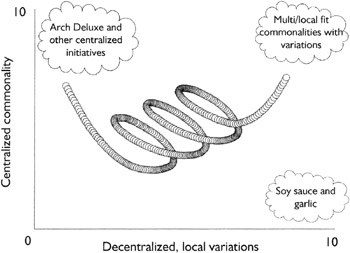

In many places, food is highly spiced. Historically this was to disguise the fact that it was not fresh; spices were used as preservatives in the days before refrigeration and gave meat a longer shelf life, especially in hot countries. Even where meat is refrigerated and in perfect condition, the taste for different spices lingers and has now become a culinary art and a local delicacy. As the dilemma in Figure 6.1 indicates, the centralized control needs to be interwoven with the variations of local taste and supply.

Figure 6.1: Centralized commonalities versus decentralized variances

On the vertical axis is the McDonald's centralized, global system headquartered in Chicago and symbolising the American Way. On the horizontal axis is the decentralized, diverse, localized variations in taste and custom, of which soy sauce and garlic are examples, deliberately chosen as variations unlikely to be widely generalized throughout the system, since these preferences might be seen as a trifle exotic.

Note that both centralized initiatives like Arch Deluxe and decentralized exotica like soy sauce and garlic contribute little to McDonald's profitability - in terms of the cost of provision and the selling price of products dressed with them. What does work is multi-localism, that is, multiple fits into a variety of markets. These may all be based on beef and buns, thereby achieving vast economies of scale. Yet local flavorings and fixings may assure customer acceptability - not only in terms of acceptable taste, but also in terms of local symbolism with which the customer can identify. In short the product is in some respects common and in some respects variant, and this combination assures wider acceptability - and more profits for McDonald's - than would otherwise be the case through sustained and increased sales.

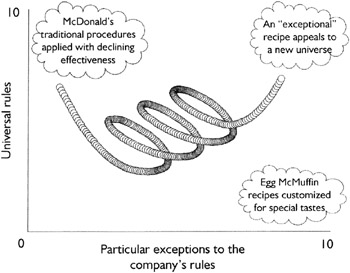

But there is a second issue of equal or greater importance. McDonald's is also in search of new product ideas and these may originate anywhere . The company has become deservedly famous by promulgating and spreading universal rules for global fast food outlets. When you discover some effective rules for satisfying customers it is best to operationalize these quickly, before your competitors do so, and achieve scale advantages. (In Boston Consulting parlance this is the "experience effect.") But all rules inevitably run into more and more exceptions, or particular preferences, that the rules have not anticipated. This does not only happen in foreign cultures, although exceptions are more likely and numerous there. It also happens in diverse regions of the US, so that the Egg McMuffin, the McFlurry, etc., originated in particular regions , while new salad dressings were discovered in France.

McDonald's has now made as much money as it can from the "old rules" of hygiene, consistency, economy, and mass marketing. Too many of its competitors are doing the same thing and it is now facing an oligopolistic challenge as a result of its success. All "universal" rules eventually encounter the limits of their universe, beyond which profits fall away quickly. "Hamburgerizing" the world is likely to prove unpopular, especially where American traditions of bland food are perceived to be imposed on spice-using countries.

All universal systems of effective rules and brands need to be renewed. How does this happen? By creating new rules that not only account for traditional customers, but the new, exceptional customers with different preferences who were in danger of going to competitors.

We have to grasp that any particular exception, when it first arises, can become part of a revised rule. Those "fussy" customers in Kyoto, Japan who want something different could be helping to create a new rule for the future. Within perhaps a year, McDonald's could be supplying sushi in all cultures with fish- eating diets.

The way in which McDonald's has reconciled universalism versus particularism, or rules versus exceptions, is shown in Figure 6.2.

Figure 6.2: McDonald's reconciliation

Thus activities might be decentralized but the information about the activities is centralized. Mass customization has become the credo of the reconciliation between standardized and universal products and customized and particular adaptations.

But McDonald's is going beyond the theme that "all business is local." The company's executives have said that they are responding to concerns of too much localization. McDonalds is in tune with its decentralized foreign operations where it actively experiments; from there it takes the best local practices and tries to use them in other areas of the world. It then globalizes the best local practices. The result is a transnational organization in which exceptions and rules modify the existing principles.

This evolution is thrown into sharp relief in times of international violence. Consider how McDonald's tries to keep the locals happy in hotbeds of anti-Americanism.

-

In France, advertisements featuring cowboys who boast that McDonald's franchises refuse to import American beef "to guarantee maximum hygienic conditions."

-

In Serbia, handing out free burgers at rallies and adding a Serbian nationalist cap to the golden arches icon under the slogan "McDonald's is yours."

-

In Indonesia, installing large photos of franchise owners making the hadj to Mecca, the staff wearing appropriate clothing on Fridays, and new TV commercials emphasizing local ownership.

-

In Saudi Arabia, a Ramadan promotion by the Saudi franchise includes a 30-cent contribution for every Big Mac to the Red Crescent and to the hospital in Gaza for treatment of Palestinian causalities.

The approach has worked in absorbing and surviving conflicts in the past. But in today's supercharged terrorist atmosphere, will it be effective in the face of the unprecedented scale of the current assault on "Americanism"?

Franchising Dilemma 2: Control versus Independent Brand Image

In addition to the fast food restaurant business, a diverse range of retail companies have also become aware of the advantages for international expansion that the franchise model may bring. This approach has been adopted not only by niche retailers, for example Benetton, Body Shop, and Yves Rocher, but also other retailers such as Casino (France), GIB (Belgium), and UK stores Marks & Spencer and BHS. Of course this has not been the only mode of expansion for these organizations; they have employed other strategies in parallel with franchising.

Franchising theory is based on the concept of the principal-agent relationship where one party (the principal) delegates work to another (the agent) who performs the work on a day-to-day basis. In the standard theory of the firm, under the divorce of ownership from control, shareholders represent the principals in the relationship and management the agents. In the context of the principal-agent relationship, agency theory highlights the importance of the information transfer process and associated monitoring costs. This information problem arises in the principal-agent relationship because agents , being in day-to-day control of a company, have detailed knowledge of its operations. The principals have neither access to this knowledge, nor, in many cases, the ability to interpret the information, even if access was perfect. Quinn and Doherty contend that the franchisor-franchisee relationship parallels the principal-agent relationship, thus allowing agency theory to provide insights into international retail franchise activity (Quinn and Doherty, 2000).

One of the fundamental aspects of agency theory is information asymmetry. For example it can occur where differing levels of economic development exist between foreign and domestic markets, where there are differences in retail regulation with regard to employment law, planning regulations, and opening hours, and where the internationalizing firm's ability to assess the risk of the foreign venture is limited due to these complexities. As such, the franchisee (the agent) has much more detailed knowledge of operations in the foreign market than the franchisor (principal).

Other examples arise where cultural practices of both consumers and management differ between the home and host countries, where human resource management practices differ , and where the degree to which domestic managers would be exported to run and better monitor the foreign operation varies.

Given the geographical and cultural distance factors, it may be proposed that supporting and maintaining an international franchise network is considered particularly difficult, and that subsequently the cost of providing franchise support is usually higher in an international as opposed to a domestic setting. In an international franchise network, it may be more feasible to use coercive sources of power.

Agency theory, on the other hand, suggests that the control and power base should rest with the franchisor. This is due to the risk of opportunism and moral hazard as a result of the existence of the significant amounts of intangible assets and the potentially high information asymmetry problem that is characteristic of the retail sector in particular. Of the types of franchise agreements that can be chosen, master/area franchising and joint venture franchising offer the retailer the greater amount of control and power. Coupled with the appropriate type of franchise agreement should be a stringently enforced franchise contract to protect the sector-specific intangible assets. However standards may be difficult to maintain in practice.

When the question of international expansion arises, a company should begin by assessing their strengths and weaknesses to determine their preparedness for it. Whether the franchisor completes the assessment or uses outside resources, evaluation should include:

-

competitive capabilities in the domestic market,

-

motivation for going international,

-

commitment of owners and top management to international expansion,

-

product readiness for foreign markets,

-

skill, knowledge, and resources to expand, and

-

experience and training.

This assessment is only a beginning and there is much more to consider before a sound decision can be reached.

Though the domestic system may use a long and well-established support infrastructure that allows reasonable and effective control to manage the system, the cost involved to build the same degree of infrastructure internationally is often exorbitant. By choosing exclusive area development as a format for international expansion, a territory of sufficient scale is awarded so that the franchisee's economic model can fund a professional infrastructure to self-support the business. The franchisee can factor in functional areas such as training, marketing, and purchasing. Using this method, the franchisor provides direct and indirect guidance and support to local professionals.

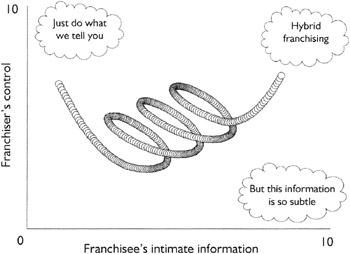

Thus this type of franchising supports two important tenets of successful international expansion: "Think local-act local," and "build franchisee self-sufficiency." Both tenets lead to high degrees of efficiency and effectiveness for both the franchisee and franchisor. Area development also benefits the franchisor by usually not discounting fees or royalties. The dilemma is illustrated in Figure 6.3.

Figure 6.3: The franchisee-franchisor dilemma

Hybrid subfranchising combines the desirable traits of master franchising with key elements of exclusive area development. It awards a large territory to a master franchisee who must first operate a minimum number of outlets and maintain a minimum percent of all operated shops . Additionally, subfranchising activity is limited to exclusive area subdevelopers. The rights for subfranchising are awarded jointly by the franchisor and master franchisee. Sub-franchisees are granted exclusive territory with a shop development requirement that exceeds a set minimum. Many of the negatives associated with master franchising are avoided using this method (Evankovich, 2003).

Franchising Dilemma 3: Exclusivity versus Broad Brand Diffusion

The last dilemma that we will consider has to do with the reconciliation of the need to extend the range of high-status products with the need to keep the scarcity that comes with a high-status brand. Let's start with a case study.

| |

V-Star is a fashion designer brand that was formally founded in 1986 by its main designer George Vallows. His first set of products was "catwalked" in Milan, New York, and Paris with rave reviews. Although many of his initial products had denim as the major fabric, Vallows extended his portfolio in the early 1990s to evening dress for both sexes, and even to designer bath fashions . After his success in the US, Vallows decided, under pressure from domestic market saturation, to go beyond US borders. He bagan wholesaling in Mexico, Canada, and the UK. With the increasing fame that he had gathered, he knew that the brand "V-Star" was the fundamental source of competitive advantage. In order to finance his growth to exploit the international potential of his brand and to build the capability to distribute, Vallows hired Merrill Lynch to help him go public. In 1996 V-Star was floated on the New York Stock Exchange, with Vallows himself retaining a 46 percent share in his company. The injection of capital allowed him to create a network of flagship stores and shops-in-shops within department stores. Before its stock market listing, V-Star did not operate any outlets outside the US and had wholesale arrangements in only four foreign markets. However, within four years of going public, the number of their company-owned stores rose to over 60 in 21 countries, while the number of wholesale markets rose to 40. The company reported that international markets accounted for almost 85 percent of total sales in 1998. This unprecedented growth should be seen in the context of worldwide sales of premium-priced branded clothing, footwear, perfumery, luggage, and other products - valued at $20billion in 1996, up from $16billion in 1992, and with sales of $30 billion in the year 2000.

However the director responsible for international retail operations for V-Star explained how adverse trading reports affected international operations in his company: Change in ownership status and the drive to exploit international opportunities had put what he described as an "unprecedented and intolerable pressure" on many of the companies concerned . With a general recognition that companies, such as Gucci and Donna Karan and V-Star, had entered the stock market with inflated share values and unreasonable performance expectations, it was generally agreed that many fashion houses had to operate under the spotlight of intense media and financial community scrutiny, and that this pressure often had an adverse effect upon international trading. Moreover the fashion market is very well informed. At V-Star the recession that hit the world economy early 2001 prompted an alternative approach so that market share could increase even further.

George Vallows and his management team discussed some alternatives. On the one hand, they could decide to extend the range of products and move into fragrances and other luxury goods to increase revenues in the domestic US and those markets with cultural proximity. On the other hand, the money could be invested to expand further in South America, Eastern Europe, and Southeast Asia. These environments are, however, culturally remote from the domestic market. What do you think they should do?

(You can find out if you were right at the end of the chapter,)

| |

The phases which the international market entry strategy of George Vallows and his company V-Star illustrates are characteristic of the industry. In a very well researched paper Moore, Fernie, and Burt (2000) describe four stages through which an internationalizing retail company quite normally meanders.

In the first stage wholesaling serves as a preliminary method of foreign market entry for fashion designers. Typically selling limited couture collections and ready-to-wear lines to the elite department stores located throughout the world, the internationalizing designers use wholesaling as a low-risk means of generating cash flow, customer loyalty, and market intelligence. Once demand has been established within capital cities and the designer's brand name has become better known within the market, edited versions of the ready-to-wear collections are made available through provincial department stores and other independent fashion retailers. This gives them a base in a market because wholesale is about immediate, focused distribution at low cost. Once this first step has been successfully taken, a second set of activities can be generally observed .

The second stage of market development involves the opening of flagship stores within capital cities. Typically located on premium shopping streets , such as Bond Street in London or Fifth Avenue in New York, these flagship stores have emerged as an important component of the marketing communications strategy of the design houses. Their role and function is vital to the development of the fashion brand's reputation. They are rarely about profit since the costs are very high and the turnovers are modest. But they support the wholesale business by creating allure since they are on the best streets and are beautifully presented. They are key to the marketing communications process.

While the main design houses have sought to maximize the profile of their flagship stores in order to promote their upmarket ready-to-wear collections, the marketing focus of the sector in the past decade has been the development of diffusion ranges. In this third stage of international development, the market expansion strategy adopted has involved the parallel launch of diffusion brands through the opening of diffusion flagships in capital cities, alongside a strategy of maximum brand distribution through wholesale stockists. This third stage is motivated by the recognition that diffusion lines make the designer accessible to the middle retail market, who have money to spend and who want the brand but are not too demanding.

Finally the fourth stage of fashion designers' foreign market expansion focuses upon diffusion ranges. Design houses (such as Armani, Versace, Nicole Farhi, and Donna Karan) have each developed chains of diffusion stores within the major cities of Europe, America, and Asia. And while the flagship stores for their main line, ready-to-wear collections are generally owned and controlled directly by the design house, the majority of diffusion stores within the UK, for example, are operated under franchise agreements. A number of reasons for this approach to foreign market expansion were provided by those design houses involved, not the least of which was the desire to avoid the significant start-up costs and the high levels of risk associated with the management of a national chain of diffusion stores.

It would be virtually impossible for designers to take responsibility for diffusion stores, for most fashion designer houses are relatively small companies and their resources are finite. So they develop a division of labor. Partners run the diffusion chains, and designer companies supply the product and most important of all, create the brand image through advertising, which has a high cost in terms of time and money.

There is a need for the fashion brand to have a clearly defined identity and personality, generated through the images presented as part of their advertising campaigns . Every successful fashion brand is based upon an image. The way that image is made is through advertising. Fashion thrives on advertising; advertising is what creates the identity and the attraction. Flagship stores are often part of a design house's marketing communications activity. While sustaining losses through the operation of many of these stores, the company often charges these against the company communications budget, on the basis that the function of the flagship store is to create awareness and interest, which is ultimately the role of advertising anyway.

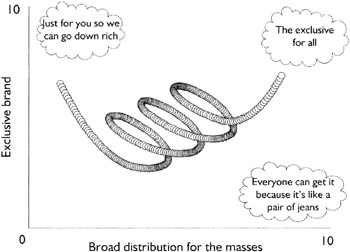

In the 1970s fashion designers often chose a product line extension strategy. Companies such as Gucci and Pierre Cardin, through seemingly indiscriminate licensing agreements, allowed their brand name to be associated with a plethora of often non-associated products: by 1980, the Gucci brand was associated with over 22,000 product lines. Such overexposure of the brand has been avoided by those companies that recognize that this undermines the sense of exclusivity and prestige which is fundamental to the image of the fashion design brand. Nevertheless, a tension still remains, in that, through the development of diffusion clothing and lifestyle product ranges, there is the danger that the prestige and allure of the brand is lost whenever the brand becomes more accessible through lower pricing and extension into a variety of product areas.

This tension between the desire to be exclusive, while at the same time maximizing the profit potential of the brand, is perhaps most evident in relation to the fashion houses' distribution policies. As was shown above, many of the retailers have, through the development of extensive wholesale distribution networks, made their brands physically available and economically accessible to an unprecedented number of consumers. This tension has lead some commentators to suggest that the fashion brands that will have longevity will be those, such as Chanel and Dior, which have continued to restrict the availability of their distribution and have also avoided the development of diffusion ranges.

On the one hand, you cannot claim to be exclusive and charge premium prices when you are selling more jeans than, say, Marks & Spencer. The customer catches you out, and American brands in particular have been caught out already. This bubble will burst and the best brands will go back to being exclusive again. Some diffusion stores will certainly close. Exclusivity is not concerned about democracy. It is possible, therefore, to question the longevity of those companies that represent international diffusion store chains.

On the other hand, looking at the demographic trends (discussed earlier in this book) we can see that many young people have chosen to go for designer fashions big time. They are accustomed to diffusion stores and therefore there is a need to diffuse these products on a large scale while still asking for exclusivity. This dilemma is illustrated in Figure 6.4.

Figure 6.4: Exclusive brands versus broad distribution

Levi Strauss has clearly shown what happens if you don't continue to be perceived as a unique, high-status brand. Few young people want to wear Levi's jeans nowadays because they are just too ubiquitous. Reconciliation lies in finding a path where a company seem to be exclusive for all. Brands like Replay, DKNY, and FCUK have done this smartly by combining mass distribution with selective chains and stores. And V-Star decided to go the same way.

Thus franchising across cultures is no longer the one-way export of a single business format, but a continuously looping feedback model that needs constant striving to reconcile the dilemmas which result from cultural differences.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 82