The State of the Art

| The prevailing approach to cost “benefit analysis in business and IT projects reflects all the problems with traditional project management. In the worst case, no effective cost “benefit analysis is undertaken and there are a series of excuses that are offered as justification. These excuses include a belief that the application of technology automatically leads to benefits or that a senior manager, politician, or client has demanded the system or that a competitor has a similar system or product that must be matched to maintain competitive advantage. In the best case, traditional cost “benefit analysis was nothing more than an exercise in mathematics. The projected cost of the new system is simply offset by a reduction of people, but there is no effective mechanism for garnishing the benefits. These token approaches to cost “benefit analysis have placed many business and IT groups in a difficult situation. Many are now seen as cost centers; that is, the internal IT group does not add value per se, but rather consumes costs and provides a service at a cost. Any benefits gathered by the service are attributed to the client group receiving the service. This model is very common in Australian and U.S. organizations and further separates the service delivery and IT people from their business clients . At worst, the service delivery and IT groups are placed in a position where their costs are being measured reasonably accurately and the benefits are left for the business groups to identify and calculate, with little capability for the IT groups to be involved in determining the benefits of their services and products.

The inevitable result of these poor approaches to cost “benefit analysis was recently summarized by senior management of an Australian bank: "We spent $500,000,000 on IT last year and have managed to identify only $50,000,000 in benefits. IT are dropping the ball." From this perspective, the organization lost $450,000,000 in investing in their IT group (clearly a candidate for outsourcing). However, in that organization, the business groups are responsible for identifying benefits and justifying projects, so the failure to effectively realize benefits is a business client problem for which IT is blamed. This issue and the following problems of traditional cost “benefit analysis have led to our group's development of a new approach to cost “benefit analysis that is explored in this chapter. Problems with Traditional Cost “Benefit ApproachesAs discussed in earlier chapters, the poor quality of most project management processes has led to serious problems in cost “benefit analysis. Limited Economic FocusMost traditional approaches to IT projects focused on a limited economic model of cost avoidance . This approach argues that the analysis of added-value benefits is complex and open to manipulation, so the only way to justify IT and business projects was to examine the projected costs of the current situation and compare these against the proposed costs of the new IT system. If the new system was cheaper than maintaining the status quo, then the project was justified. This approach ignores any added benefits associated with the new technology and system and forces a focus on cost reduction, generally through staff reductions. The cost-effectiveness model has probably been the most widely used in computing and, although useful for functional replacement projects (see later), is not suitable for the new generation of IT and business projects. Intangible BenefitsThe de facto endorsement of intangible benefits has been widespread, especially in very competitive industry segments. Projects have been justified on fuzzy benefits such as improving competitive position, being aligned with a vendor's architecture strategy, improving company image, or improving global reach. The problem with intangible benefits is that they remain intangible and unmeasured. In effect, the use of intangible benefits encourages the nonmeasurement and quantification of benefits that, if measured, would significantly improve the organization's understanding of their business, their clients, and their environment.

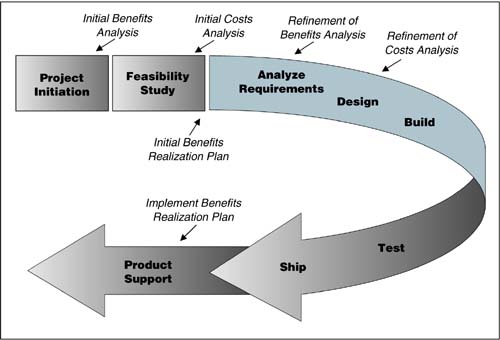

More important, the analysis of intangible benefits using the techniques covered later offers significant areas of financial benefits for projects. The use of shadow pricing and contingent valuation techniques, which have been developed over the past decade , can provide dollar values for benefits that were previously treated as intangibles. Lack of Benefits Realization PlanningAs discussed earlier, the traditional approach to cost “benefit analysis (and project management, in general) did not involve business clients in any meaningful manner. The arms length model of project areas such as IT as a service provider left business people alone to determine and garnish benefits. As a result, through lack of education, effective cost benefit analysis models and accountability, many business people have sponsored projects that eventually did not provide the benefits expected. A typical example of this is justification of a project on the elimination of five staff positions, but no one is accountable for the redeployment of the five people currently in the positions . The process of benefits realization planning is critical to advanced project management and involves a partnership among the IT service providers, the business clients and, in many cases, external stakeholders. Early CommitOne of the paradoxes in cost “benefit analysis is inherent in the nature of the system or product development process. As shown in Figure 9.2, the analyzing of benefits is associated with the objectives of the project, which are often identified at the beginning of the project initiation and business analysis phases. As a result, it may be possible to both identify and quantify the proposed benefits for a project during project initiation. Figure 9.2. Cost “benefit analysis However, the estimation of costs depends on the selection of the design options for the system and, in most cases, this will not be known accurately until the end of the requirements analysis stage (at best) and the end of the design phase (at worst). In other words, the estimation of costs and benefits occurs at different stages of the development process. However, it is expected in most organizations that both the costs and benefits are calculated at the beginning of the project. This approach reflects the engineering background of traditional project management where the costs of a building or appliance can be identified through accurate historical project metrics. The reality in many IT projects is that the technology is so dynamic and estimation metrics are so poor that even if there could be some estimates made of costs during the feasibility study, new technology and design options would probably emerge during the development process. Put simply, benefits can be estimated early but costs can only be estimated later. Poor Costing ModelsThis is a serious problem in all projects. There are a number of major problems with the mechanisms used to track costs. These include the following:

These are covered in more detail on our Web site (www.Thomsett.com.au). The Ultimate FiddleProbably the most serious issue in traditional cost “benefit analysis is the lack of the whole of life model that is the basis of our eXtreme project management approach. As we discuss in more detail in Chapter 18, "Postimplementation Reviews," the lack of inclusion of the support costs in a cost “benefit analysis is a major fiddle. For example, assume that the project is going to cost $10,000,000 in development. The estimated benefits are $15,000,000. In many organizations, the analysis of costs and benefits would simply involve the development costs ($10,000,000) being subtracted from the benefits ($15,000,000), leading to a profit (return on investment) of $5,000,000. However, the whole-of-life model in eXtreme project management would require the product support costs to be included in the virtual financial analysis. [2]

In our example, assuming that support costs were $10,000,000, then the whole-of-life costs would be $20,000,000 (not $10,000,000). This would mean that instead of a ROI of $5,000,000, the project would suffer a loss of $5,000,000. |

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 136

- An Emerging Strategy for E-Business IT Governance

- A View on Knowledge Management: Utilizing a Balanced Scorecard Methodology for Analyzing Knowledge Metrics

- Technical Issues Related to IT Governance Tactics: Product Metrics, Measurements and Process Control

- Managing IT Functions

- The Evolution of IT Governance at NB Power