COMPANY AND PRODUCT LIFE CYCLE

Businesses, like governments , like all institutions created by human beings, are mortal. In the course of time they are created, enjoy their season , and then vanish . Their evolution can be traced through four stages ” tryout, growth, maturity, and decline.

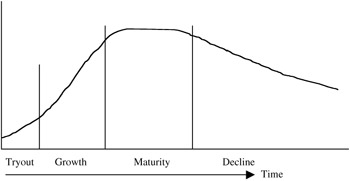

Products, too, have a limited life, and if a demand for them develops, they can be expected to obey a somewhat similar pattern, that depicted in Figure 15.1. Although few companies or products will imitate this design exactly, the concept is useful in forecasting sales and cash flow.

Figure 15.1: Life cycle of a typical company or product.

The tryout period is one of experimentation, finding the product, the price, the method of distribution, the niche that will create customers. If and when the growth stage develops, a heavy investment in promotion and production is needed. During this period, which may last a decade or two, it is usual for more cash to be spent than received, even though the operation is highly profitable. With maturity the cash flow turns positive as sales level off. The last stage is the least predictable, some companies going out with a bang, some with a whimper, others merging themselves quietly into the operations of a more viable firm.

CASH FLOW

Cash flow has been defined as:

Profit + Depreciation

In recent years a new definition has been taking shape:

Profit + Depreciation + Deferred Taxes

Cash flow is intended to represent "discretionary funds" that are over and above what is needed to continue running the business, and may, therefore, be used to expand the company, pay off loans, pay extra dividends , and so on.

When it was first conceived, the idea of adding profit and depreciation to get cash flow found overnight acceptance among business executives. If profit was vanilla ice cream, cash flow was a chocolate sundae. But it also produced an unwanted side effect ” "the non-cash illusion."

Cash flow is a popular term with business managers. It is a phrase that is vague enough to make you sound like you know what you are talking about even when you do not. It is also useful in cases where you do know what you are talking about but do not want to talk about it. As when a supplier calls you about an overdue bill. Which would you rather say?

"We do not have the money right now."

or

"We are experiencing a temporary cash flow problem."

The latter statement conveys your understanding of mysterious economic forces and implies that the solution to the problem is just around the corner. Unfortunately, such a fine phrase as "cash flow" has been used in so many different ways you have to verify its meaning each time you hear it. Often, as in the example above, it means the same as "cash"; but sometimes it is the amount of cash flowing into the business each month or year; at other times it is the difference between the inflow of cash from sales and the outflow for expenses; and to those who enjoy elevating obscurity to its highest plane it is "the funds available as working capital and for expansion." Most of the time when professionals, especially financial professionals, speak of cash flow they are talking about the specific dollar amount derived by adding depreciation back to profit.

When we analyze cash flow we are asking what activities brought money into the business and what activities caused it to flow out. In the simplest terms, where did the cash come from, where did it go? Most of the cash coming into a business is the proceeds of sales; most of it going out is to pay expenses. So we can start our cash flow analysis with the difference between the two, which is profit.

Profit = Sales - Expenses

Included in the expenses is depreciation and maybe amortization, but these are non-cash expenses; that is, there is no money paid out for this expense because it was all paid out at the time the asset was bought.

The concept of cash flow is lame in one respect. It fails to recognize the need to replenish fixed assets. Plants and equipment must be replenished, just as inventory is. To say that funds from depreciation do not have to be spent on new fixed assets is as deceptive as saying that cash received from a sale does not have to be spent to buy new merchandise. (If you need any further convincing, look at some published annual reports ” the statistical section where you often find figures for depreciation and new capital investment going back five or ten years. Count the number of years that the value of new equipment exceeded the depreciation charges; chances are it will be at least nine times out of ten.) In other words, companies are not only using all of the depreciation money to buy new fixed assets, they need a good deal more besides. A better formula for calculating cash flow would be:

Profit + Depreciation - New Fixed Assets

Even if a company is not growing, chances are that inflation will push replacement costs higher than depreciation rates.

A FINAL THOUGHT ABOUT CASH FLOW

Because of the non-cash illusion, the concept of cash flow has little relevance to day-to-day management. It is useful in calculating the return on proposed capital investments, as we will see later, but for the management of cash and cash planning it is not. Those activities are best managed with detailed budgets and forecasts. Moreover, the mystique of cash flow has been known to replace common sense, as in the airline industry where enormous depreciation charges often mask treacherous losses; likewise in some tax shelter schemes where non-cash charges are used to reduce taxes and thus appear to actually generate money.

In the last analysis all firms, all tax schemes, must be profitable to be successful. Profits are the true test of any investment, and to the extent that cash flow confuses this ultimate reckoning it does us a disservice.

It is apparent that a company can lose money and still have a positive cash flow. What is not so clear is that a firm can have a positive cash flow and still go broke ” a common hazard for rapidly growing companies.

The term "working capital," like the term "cash flow," is frequently heard in the daily chatter about business finance. It, too, suffers from liberties taken with its definition and usage. Most often, and especially when financial people are talking, working capital means the specific dollar amount derived from the formula

Current assets - Current liabilities

However, it has also been used to mean "cash," or "cash + receivables," or "current assets," or "funds." When it comes to applying the idea of working capital in some useful business way, we encounter two nearly fatal flaws.

-

Working capital is a concept that has no existence in the real world. You cannot hold working capital in your hand or put it in your pocket. Nor can you actually offset current liabilities with current assets. Nearly all current liabilities can only be satisfied with cash.

-

While businesspeople are fond of calculating working capital, no one has yet come up with a rule stating how much of it a company should have. It seems reasonable enough that the more sales a business has, the more working capital there should be also. But we cannot seem to pin it down to an actual standard. Working capital, therefore, is a measurement without much meaning. In business there is only one excuse for an expense: it will help to produce revenue.

Some expenses, however, have nothing to do with producing revenue ” the entire accounting department, for example ” but they are necessary nevertheless. Others, such as income tax and vacation pay, have only a roundabout effect on your sales but are also unavoidable. Some pay our debts to society, such as the expense of unemployment insurance, or make us good neighbors, such as a little landscaping, while the sole purpose of some expenses is to reduce overall expense, that is, increase productivity.

Unlike revenues , which are the result of a customer taking action, expenses result when you take action. They are largely controllable and therefore a direct reflection of your management ability. It may be hard to measure the value of what you do, but the cost of your doing it is right there in the printout for all to see.

A HANDY GUIDE TO COST TERMS

- Actual

- Actual costs are distinguished from standard costs; the latter are estimates used for convenience, and an adjustment must be made to the actual costs at least yearly.

- Alternative

- The costs of optional solutions; used in "what-if' analyses.

- Controllable

- Costs for which some manager can be held responsible.

- Cost of Sales

- Also called "cost of goods sold"; the cost of making or buying the products a business sells. In a manufacturing firm it comprises direct labor, materials, and manufacturing overhead.

- Differential

- The difference in the costs of two or more optional activities.

- Direct

- Costs that can be laid solely to a particular activity. In manufacturing, the wages of the workers who make the products and the cost of the materials used are direct costs; they are often referred to as "direct labor" and "direct materials."

- Discretionary

- More or less unnecessary but desirable outlays, such as the office Christmas party or management seminars .

- Estimated

- Predetermined by an informed guess.

- Extraordinary

- Expenses due to abnormal events, such as an earthquake. Costs in this category should be not only unexpected, but rare.

- Fixed

- Costs that remain the same despite changes in sales or some other output. Examples are lease payments on property and depreciation on equipment. Compare to variable costs. As used here the fixedness is a matter of degree; almost every cost is affected somewhat by the volume of sales.

- Historical

- The original cost of an asset.

- Imputed

- The imagined or estimated cost of a sacrifice; not a cash outlay but the giving up of something you could have had; a cost often recognized in the decision process but not recorded on the books. When a company has accounts receivable, for example, there is an imputed cost of the interest it could be earning on the funds tied up in receivables.

- Incremental

- A cost that will be added or eliminated if some change is made. Similar to "differential cost."

- Indirect

- A general or overhead cost that is allocated to a product or department on the theory that the receiver shares in the benefit of the thing, and, besides, somebody has to pay for it.

- Joint

- Also called "common cost"; A cost shared by two or more products or departments, as for example the expense of a company lunchroom.

- Noncontrollable

- Costs that are prerequisites to doing business, such as a city license or smog control equipment. These costs are often allocated to a department, but there is no point in holding the manager accountable for them.

- Opportunity

- A theoretical cost of not using an asset in one way because you are using it in another. For example, the opportunity cost of a company-owned headquarters building is the money the company could get by renting it to others.

- Out of Pocket

- Expenses requiring a cash outlay, as opposed to the expense of using facilities you already own. When you use your car for company business, the cost of gas, tolls, and parking are out of pocket expenses, but not the depreciation on the car.

- Period

- Costs related to a time period rather than an amount of output or activity. Examples are rent and the controller's salary.

- Prepaid

- Expenses paid before, rather than as, they are used. A prepaid expense, such as a year's insurance premium, is really a current asset that gradually converts to an expense with passing time.

- Prime

- In manufacturing, direct labor and material costs.

- Product

- Costs related to output or the amount of activity, as opposed to period costs.

- Production

- A term used by the oil and gas industry in referring to the cost of operating a well.

- Replacement

- An estimate of the current cost of an asset as contrasted with its historical cost. It is often used in estimating the "true" cost of the current year's depreciation.

- Standard

- The estimated average or budgeted cost of making a product. When a product is finished, it is often more convenient to record its value at a standard rather than its actual cost. At least once a year the total actual costs are compared with the total standard costs recorded, and the latter is adjusted to the real figure. Standard costs must be changed from time to time if labor and material costs change.

- Sunk

- A cost already incurred that cannot be undone or readily put to some other use.

- Variable

- A cost closely tied to the level of output or activity. Most of these costs vary directly with sales. Classifying costs between variable and fixed is necessary in order to calculate a breakeven point.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 235