ACCOUNTING FUNDAMENTALS

ACCOUNTINGS ROLE IN BUSINESS

To understand accounting's role in business we might first look at the principal task of management. The manager's job is to control and direct the business affairs under his or her command. To do so, the manager must understand the effects of past business transactions and thereby be able to estimate the effects of proposed future undertakings. Accounting has the dual role of (1) recording every occurrence that has a financial impact on the business, and (2) reporting these financial data in a form useful to management. Let us first look at the reports that accounting prepares for management, then later at the way transactions are recorded.

FINANCIAL REPORTS

The balance sheet, income statement, and other reports summarize the results of a company's activities. When all of the talking is done, it is to them you look to see how well the company is really doing. This is done through an evaluation of the assets, liabilities and owner's equity or a balance sheet.

Accountants are financial historians. Their task is first, to record every event in the life of a business that has a monetary impact; and second, to report those proceedings in forms that show management how far the company has come and in which direction it is heading.

The Balance Sheet

"Balance sheet" is the age-old name of a report that sets forth the assets, liabilities, and equity of a company. As accountants have become more educated and higher priced they have tried to substitute fancier names such as "statement of financial position" or "statement of condition," but the old name lingers on. There are two important balancings or equalities in this report. The first is usually referred to as the "balance sheet equation":

Assets = Liabilities + Equity

The counterpoise of these factors is the essence of the double-entry bookkeeping system, which says that for every action there is a reaction, for every benefit received a benefit bestowed, or an obligation to do so. Thus, for every dollar of assets owned by a company, someone among the creditors and shareholders holds a claim check.

The other equality in the balance sheet is hidden, or rather, undisclosed. Although each item listed has a dollar value, there is another quality about it that is not revealed: The dollar amount is either a debit balance or a credit balance. The assets have debit balances while the liability and equity accounts have credit balances , so that on every balance sheet

Debits = Credits

In our system of accounting, debits also represent expenses on the income statement, while revenues normally have a credit balance.

The balance sheet represents the condition of the company on a particular day ” in fact, the last working moment of that day. Every subsequent transaction changes it to some degree; an employee coming through the door to work the next morning, for example, starts the meter running on the liability called accrued salary expense. An undated balance sheet, therefore, is meaningless.

Most condition reports actually give two balance sheets ” the current one and one from the year before ” so that a quick comparison can be made. Often, the changes in a balance sheet, from one year to the next, are more significant than the ending numbers themselves .

Current Assets and Liabilities

The balance sheet is normally divided by debits and credits; that is, the assets appear on the left side (or at the top), while the liabilities and equity accounts are on the right (or on the bottom half of the page). On each side (or in each section), the items are listed in the order of their exigency: their nearness to being converted to cash in the case of assets; their nearness to being paid off in the case of liabilities and equity.

In the evolution of the various assets to and liabilities to maturity, a sharp line is drawn at one year beforehand. Those assets such as inventory, accounts receivable, and cash itself that are expected to convert to cash in the ensuing twelve months are called current assets. Likewise, those debts that will come due before the next annual financial statement are classified as current liabilities. The accuracy of these classifications is important in measuring a company's liquidity ” its ability to pay debts on time.

Fixed Assets

Items that are used in running the business, as distinguished from those things that are made or held for resale, are called fixed assets. Fixed assets are typically listed below the current assets, something like this:

-

Property, plant, and equipment

-

Less: accumulated depreciation

-

Net fixed assets

Accumulated depreciation shows how much of the cost of existing fixed assets has been expensed. It amortizes the cost over a period roughly akin to the useful life of the assets. Here is the accounting entry for the yearly write-off:

-

Debit: depreciation expense

-

(An income statement account)

-

-

Credit: accumulated depreciation

-

(The balance sheet account)

-

Accumulated depreciation has a credit balance. When it is listed, therefore, among the assets (which are debit balances), it is a negative amount.

Other Slow Assets

"Slow" refers to the fact that in the ordinary course of business these assets are not likely to be converted to cash in the coming year.

Goodwill represents the premium over book value paid by one company when buying the assets of another. Down-to-earth accountants call goodwill, goodwill. Others label it something like, "Excess of cost over book value of acquired assets..." For example, Company A has assets with a book value of $1 million. Company B negotiates to buy those assets for $1.2 million. The accounting entry on B's books would look like this:

| Debit: Assets (various kinds) | 1,000,000 |

| Debit: Goodwill | 200,000 |

| Credit: Cash | 1,200,000 |

Because goodwill represents one buyer's estimate of a worthwhile premium, bankers and other financial analyzers often eliminate it from consideration as an asset. (More on that later.)

Current Liabilities

Obligations that are due to be paid are called current liabilities. Current liabilities is an important classification to analysts because it represents money that must be paid from future receipts. Most current liabilities are renewable (or revolving), as long as creditors have confidence in the debtor.

Working Capital Format

Now and then you will see a balance sheet in a "working capital" format. (Working capital equals current assets minus current liabilities.) The layout might be something like this:

| Current assets | $1000 |

| Current liabilities | 500 |

| Working capital | $500 |

| Other assets | 1200 |

| $1700 | |

| Other liabilities | $800 |

| Shareholders' equity | 900 |

| $1700 |

While the creators of this format probably had good intentions, it is confusing to read and even irritating because there is no figure for total assets. The working capital figure is of little use and may even be harmful if it is taken to be something it is not. You may subtract current liabilities from current assets on paper, but you cannot do it in real life; current liabilities are reduced only by cash.

Noncurrent Assets

The noncurrent assets are those that take longer than a year to liquidity (e.g., long- term receivables), and those that the company has no intention of selling, such as property, plant, equipment, vehicles, and other so-called "fixed assets." The fixed assets are listed at what they cost, less depreciation, and on the balance sheet itself no attempt is made to show their current market or replacement value.

Intangible assets such as patents, organization expense, and goodwill (usually called something like "cost in excess of book value of acquired assets") are also shown in the noncurrent assets section, although they may not be labeled as "intangible."

Noncurrent Liabilities

Among the noncurrent liabilities are bonds payable and other "long-term debts," deferred compensation, and maybe accrued pension liabilities. Any part of these obligations that falls due within the next 12 months is listed in the current liability section. Also frequently found here is the deferred income tax account, which is a liability in theory but seldom in practice; accountants (and everybody else) are so unsure about how to categorize this account that they usually skip giving a total liability figure on the balance sheet just to avoid having to classify it.

On about one out of five balance sheets you will run into "minority interest." It is usually found in between liabilities and equities because it is neither one nor the other. Minority interest represents the outside shareholders of not fully owned subsidiary corporations; the amount is not payable to them unless the subsidiary is closed down and liquidated.

Shareholders' Equity

The remainder of the balance sheet is given over to the equities. Some accountants refer to them as a form of liability. They are ... if you strain a little and reason that the company assets that are not owed to the creditors are owed to the stockholders . But in modern usage, equity is distinguished from liabilities, which are obligations to make payments on specified dates. Shareholders may be entitled to the equity share of the assets, but "cashing out" is a practical impossibility unless a majority of them act to liquidate the company.

Of course, shareholders may sell their interest if the stock is publicly traded or they can find a buyer. Stockholders of today think of themselves more like depositors in an institution than owners of a company. The security, comfort , and convenience of modern investing has been purchased with the power and influence shareholders once had.

As we stressed earlier, the balance sheet is constantly changing, and the changes year to year often give a clue as to where the business is heading. That information is given in the statement of changes, discussed below, but one item in the equity section ” retained earnings ” has a whole separate report to show how much and why it changed. That report is called the income statement.

The Income Statement

This statement is a report of a company's sales, less the expense involved in getting those sales, and the resulting profits. It used to be called the "profit and loss" statement ” and was nicknamed "P&L" ” but in the turbulent sixties corporations became sensitive to the word "profit," and it has all but disappeared from their public utterances. (Nonprofit organizations are supersensitive about the word, as you might imagine, and refer to their profits as the "excess of revenues over expenses," or some such dignified euphemism.)

Income statements begin with the grandest number found in the business, revenues...the fount of all profits. In most firms the term "revenues" means sales, but there may be other forms of revenue, too ” interest income, rents, royalties, and so on. The sales figure is usually "net" of returns and allowances.

Gross Profit

The rest of the income statement is a process of distilling the revenues by boiling off expenses at various stages until you are left with the essence of net profit. The figures you get along the way vary in importance. The first step is the deduction of the cost of sales (or cost of goods sold) ” the largest expense in most companies.

Sales - Cost of Sales = Gross Profit

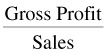

From these figures you can derive the gross profit margin (it is rarely given in the report)

=Gross Profit margin

=Gross Profit margin

Gross profit (GP) and gross profit margin (GPM) are important because they reflect the basic climate of the business. In the typical firm, the gross profit margin will not vary more than two or three percentage points from year to year. If the figure is trending down, it may mean the company's product line is getting old or the pressure from competitors is increasing ” both of which are major problems.

A Gaggle of Profits

Like a gaggle of geese whose symmetrical formation in flight points gracefully toward their goal, profit calculations often taper gently inward as they descend to a point on the bottom line. Along the way you might find figures for:

-

Operating income

-

EBIT (earnings before interest and taxes)

-

Income before nonrecurring items

-

Income before extraordinary items

-

Income from continuing businesses

-

Income before taxes

You might well ask whether all these numbers clarify the profit picture or deform it. Perhaps the biggest benefit of EBIT is that it gives management a bigger number to talk about. Most companies borrow money and pay interest with regularity; they would not stop if they could, which they cannot, so there is not much point to deriving a profit without such a routine expense.

The same could be said for profit before income taxes. It is like saying "look how much money we could make if we did not have to pay taxes." So what? It would be as useful, and perhaps more interesting, to show us "income before president's salary," or "income before expense accounts."

On the other hand, the income before nonrecurring expense or rather, the nonrecurring expense itself can sometimes be revealing . Most often these charges are the bite-the-bullet kind; the company has a losing product or division or subsidiary that management decides to dump.

There is some psychology at work here. The thought of profits being attrited year after year by some feeble division is depressing; the cost of getting rid of such a ball and chain is almost inconsequential, so long as it can be tagged nonrecurring. Management is saying "sure, there have been some problems or mistakes, but now they are behind us and we can look to a brighter future."

If you find such a write-off in some company's glossy annual report, just turn to the front pages where the recent acquisitions and new products are described with unfettered optimism ; see if you can guess which of them will be tomorrow's nonrecurring expense.

Earnings Per Share

The income statements of public corporations also give an earnings per share (EPS) figure. From the net income is deducted dividends , if any, on the preferred stock, and the remainder is divided by the number of common shares outstanding.

The Statement of Changes

The Statement of Changes in Financial Position is descended from a family of "funds statements" that include (a) the sources and applications of funds, (b) the sources and uses of cash, and (c) the where-got, where-gone statement.

The purpose of the report is to describe whence money has come into the business, and how it has been used. There are, of course, thousands or millions of little pieces to that puzzle, so the statement of changes does some wholesale netting to get the report down to a manageable size .

All of the transactions involving sales and expenses are combined in a net income or loss figure; to this are added back those deducted expenses that did not take any cash, such as depreciation, amortization, and deferred income taxes. The total of these items is often called the "sources of funds from operations." The changes in the current accounts may be grouped together as a change in working capital (current assets minus current liabilities).

Sources of Funds or Cash

Besides the profits and noncash expenses, any increase in a company's liabilities is considered a source of cash. Think of borrowing from a bank; you sign a note that increases your debts, and you walk out with a pocket full of cash. On the other hand, any decrease in assets is also a source of funds ” as when you sell one of your trucks for cash.

Use of Funds

Typically, the principal use of funds is for additions to property, plant, and equipment; also found here are increases in other slow assets, dividends paid, and net reductions in debts. A balancing figure ” the change in working capital ” is either included here or listed just below this section.

Changes in Working Capital Items

Some statements of changes have a section showing the changes in current assets and current liabilities. The net changes in the current assets ” please pay attention, this is not easy ” the net changes in the current assets minus the net changes in the current liabilities equals the net change in working capital. This figure will match the change in working capital calculated in the sections dealing with noncurrent assets and liabilities and equity.

Say what? If after this simple explanation of the statement of changes you feel as if your brain is turning to mush, be assured it is not your brain that is the problem; it is the statement. Anyone can have a dud in his or her bag of tricks, and this is one the accountants have. The statement is hard to understand and has so many exchangeable opposites that the words increase and decrease tend to lose their meaning after a few minutes.

Not many people, I have found, bother to read this report; but of the non-accounting stalwarts who do, most fail to understand it, or worse , they misinterpret it. Nevertheless, the changes in the balance sheets, one year to the next, may be important. If that is the case, you can usually get just as good information ” and sometimes better ” by simply subtracting the side-by-side numbers in the two balance sheets listed, rather than from struggling with this unfortunate report.

The Footnotes

There is a cliche among analysts and accountants that the real lowdown on a firm will be found in the footnotes. There is usually plenty of information there, all right, maybe four times again as much as in the financial statements themselves. But the footnotes in a financial report are, like footnotes anywhere else, related information of lesser importance. Anything with a serious financial consequence will be expressed on the statements, and while additional details can often be found in the footnotes, they may or may not be of interest to you.

A classic example on footnotes is the 1986 annual report of General Motors Corporation. It had a total stockholders' equity figure on its balance sheet of $30.7 billion. In the footnotes, however, there was more than a full page of crammed data that reconciled changes in amounts for five different classes of stock, capital surplus , and retained earnings. While it may give some people comfort knowing that the extra information is there, for most readers it is not likely to add anything to the impression made by the single number. We suggest, therefore, not to bother with the footnotes unless you have a particular need for more details about an item.

Another reason to go easy on the footnotes is that the language there is largely technical, and if you are unfamiliar with it you might be led to a wrong conclusion. Besides, all of us in business these days have more information available to us than we have the time to look at it. Excessive information is no friend to a good decision, and it is an enemy to action.

Accountants' Report

Financial reports that have been audited by "independent" CPA firms will contain a letter from them stating the scope of their involvement and giving their opinion about the financials. It is usually written in accounting boilerplate .

If the letter is signed by an accounting firm, and it contains "in our opinion," if it does not contain "except for" or "subject to," and if it has no more than a few sentences, you are looking at a "clean" opinion and can feel very comfortable about the figures. For any exceptions to the above you had better wade through the whole letter ” depending on how important it is to you.

How to Look at an Annual Report

Since I have looked at quite a few financial reports over the last 30 years , allow me to recommend a best way to go about it. The fact is, that there is no one best way for everybody. It is an individual thing, a little like the way you observe a member of the opposite sex walking toward you. You look first at one thing, then another, and if you are still interested you may turn around and look at a third. But each person develops the pattern that suits his or her own individual needs. Same with financials, so here is my pattern.

-

Step 1 . Look first to see if the statement has the independent clean opinion described earlier. Anything less means that you need to take a more careful look at the numbers (i.e., testing them against poor common sense and experience), and read every single word on the statements.

-

Step 2 : Turn to the income statement and look at:

-

The latest net income figure. A loss is a red flag.

-

The prior year's net income to see the direction of profits. Two years' losses back to back means standby the lifeboats.

-

Total revenues or sales to see the direction they are heading. Sales are a proxy for demand for the product ” the single most important requirement for success in business.

-

-

Step 3 : Now the balance sheet. Here is the sequence I follow:

-

Right side, second to the last figure from the bottom ” shareholders' equity. Compare it with last year's figure; if the company was profitable, equity should have gone up. Now compare it with the bottom number (total debt plus equity) just below; if the bottom figure is more than twice the equity, the firm may have too much debt.

-

Run your eye up the page to the total current liabilities amount; remember the number (rough rounded).

-

Now over to the current assets. Check the total of that section; if it is only slightly higher than the total current liabilities, that is bad; twice as much is good.

-

Finally, look at cash (plus marketable securities). If it is less than 1/10 the current liabilities, it is not so hot; a good ratio would be 30% or more.

-

-

Step 4 : The next step is to sit back and reflect for a moment. You have made mental tests of statement reliability, profitability, leverage, and liquidity; now form a preliminary opinion of the overall condition: excellent , good, fair, poor, or lousy. If you have a mixture of good news, bad news and/or you have to explain your judgment to others, go on to Step 5.

-

Step 5 (Optional): For a second opinion, ask for professional advice.

You will recall that we started this section by saying that accountants have a dual role in business: (1) to record every financial transaction, and (2) to report this financial data in a form useful to management. We have looked at the reports prepared by accountants. Now let us examine how transactions are recorded.

The history of humankind, that is, the written record of human activities, goes back about ten thousand years. The earliest evidence of writing that we have discovered consists of some lumps of clay on which Sumerian farmers recorded their livestock ” what we might fairly term "accounting records."

Today almost all accounting is done by the double-entry bookkeeping method, which was developed by the Roman Catholic Church. Thus the term "accounting clerk" derives from the word "cleric." The first evidence of this system dates back to Genoa, Italy in the fourteenth century.

I think we would all agree that the accounting profession has had plenty of time to settle on all the right procedures. But judging by the changes still going on in accounting, and the liveliness of the debates about them, you wonder if the development of accounting is even half complete.

One reason for the continual changes may be that there is no unifying theory of accounting similar to, say, the supply-demand concept of economics or the ego--id theory of personality. Instead, accounting is based on conventions, that is, rules established by general consent , usage, and custom. These rules are called generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), and they change from time to time. Accounting, then, is very much alive ” if not completely well ” and the challenges and opportunities it offers to good management are as fresh as ever.

RECORDING BUSINESS TRANSACTIONS

Every business transaction involves both give and take. The double-entry bookkeeping system is an ingenious method of recording these activities in a complete, quick, and puzzling manner.

The double-entry bookkeeping system (there are also single-entry systems ” your checkbook is an example) dominates accounting in all the industrialized countries . The outstanding characteristic of this system is that it records both sides of every transaction, and every commercial transaction has two sides: there is the thing you give to the other party, and the thing you take in return. To account for a piece of business this give and take must be expressed in dollar values, and the double-entry system always records an equal dollar amount. Profit or loss is frequently part of the transaction ” the factor that makes the give and take balance.

Debits and Credits

The terms debit and credit were devised to represent the take and the give; they are from the Latin language because our modern accounting system traces its origin to Catholic clerics of the fourteenth century. In general, debits represent what is taken from a transaction, and credit what is given up. Debits and credits have no more meaning than that, and we could just as easily have chosen other terms in their place, black and red, for example, or left and right.

Of course the words debit and credit have other meanings in our language, but it will only confuse you to try to match them with the narrow usage in accounting. Table 15.1 summarizes the use of these terms in accounting.

| Debits | Credits | |

|---|---|---|

| Abbreviations | Dr | Cr |

| Represent what is | Taken | Given |

| They often designate what is | Owned | Owed |

| Or sometimes | Benefits received | Money spent |

| They are also the normal balances of | Assets | Liabilities |

| Expenses | Equity | |

| Revenues |

Sources and Uses of Cash

In order not to make this come too easily to the uninitiated, financial people sometimes define debits as the uses of cash, and credits as the sources of cash. These are what I call definitions +; normal definitions plus one mental broad jump. Debits are said to be uses of cash because when cash is spent (that is the credit part of the transaction), something such as an asset is taken and recorded as a debit. They make a similar convolution to label credits as a source of cash. If you borrow money from a bank, the cash they give you is a debit ” something received, an asset ” but the source of that cash was the bank loan ” a liability and a credit.

How Debits and Credits are Used

Every item ” asset, liability, or equity ” on the balance sheet has a dollar value assigned to it; it is the company's and their CPA's best estimate of the worth of that item. But each account also has another quality about it, one that is hidden and not expressed: Every dollar amount on the balance sheet is also either a debit balance or a credit balance. If you look back at Table 15.1, you will see that assets are debit balances, while the liabilities and equity accounts are credits.

The Balance Sheet Equations

You will recall our earlier discussion of the balance sheet equation:

Assets = Liabilities + Equity

And from the foregoing you can see also that

Debit balances = Credit balances

They will stay that way so long as every future transaction is recorded with equal amounts of debit and credit dollars.

Forget + and -. In the use of debits and credits, they do not stand for plus and minus. Both may be either; it depends on the account they are applied to. If a debit is applied to an account that already has a debit balance, the two amounts are added together, and a larger debit balance results. If a credit is applied to an account with a debit balance, then the amounts are subtracted from one another. A similar rule holds for accounts with credit balances. Debits and credits, in other words, are added to their own kind but subtracted from their opposite number.

CLASSIFICATION OF ACCOUNTS

In accounting there are five basic types of accounts. On the balance sheet: assets, liabilities, and equity. On the income statement: revenues and expenses. In Table 15.2 is a summary of their normal debit/credit balances.

| Normal Balance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Definition | Debit | Credit | Balance Sheet | Income Stmt |

| Asset | What is owned | x | x | ||

| Liability | What is owed | x | x | ||

| Equity | The rest | x | x | ||

| Revenue | Sales, etc | x | x | ||

| Expense | Costs | x | x | ||

| The Balance Sheet | The Income Statement |

|---|---|

| Assets

Liabilities

Equity

| Sales

Gross Profit Selling and Administrative Expense Interest Expense Other Income and Expense Income Taxes Net Income

Added to Retained Earnings |

Recording Transactions

Remember the basic rule in accounting that in the recording of a transaction debits must equal credit. We can readily see that every business dealing has both a give and a take to it. When a company buys merchandise it takes the goods and gives money in return. The opposite occurs when the goods are re-sold. When it hires a worker, a company takes the fruits of his or her labor and gives back cash in the form of wages . In a broad sense, debits represent the take in a business transaction, and credits the give.

For example, your company buys a new computer, paying $900 in cash.

| Debit (Dr) | Office equip | $900 |

| Credit (Cr) | Cash | $900 |

The give and take aspects of double-entry accounting are easily seen here (they are not always so readily apparent). The debit is what has been received; the credit is what has been given in exchange; the debit also represents a use of cash. In this example, both of the affected accounts are assets. The cost of the computer will be added to the cost of previously acquired office equipment, which is already shown on the balance sheet as an asset (debit). As we are combining a debit entry with a debit balance, the result will be a larger asset account on the next balance sheet.

However, the cash used to buy the computer was also an asset (debit). Now when we combine the credit to cash with our beginning debit balance of cash, the result is a smaller debit balance of cash. Since only assets were affected by this transaction, the total of assets was unchanged. There were no effects at all on liabilities, equity, revenues, or expenses.

Another example: Your company makes a sale amounting to $2150. As soon as an invoice is issued, the accountants will record the transaction. If the sale is for cash the entry will be

| Dr | Cash | $2150 |

| Cr | Sales | $2150 |

In this situation, both entries are plus amounts. The debit is added to Cash and the credit is added to Sales, for Sales is a revenue account that normally has a credit balance.

| Note | In this case there are no effects on liabilities, equity, or expenses. The cost of the goods that were sold will be recorded in a separate transaction at the time we derive a new inventory figure. |

The Two Books of Account

The transactions we just looked at and similar ones are recorded in a book called the General Journal. It sets out in chronological order all of the firm's business dealings. It is like a diary of business transactions. Large firms have special journals, such as the Cash Receipts Journal, for recording certain classes of transactions, which are summarized at the end of the month or year in the general journal.

The second book of account is the General Ledger (GL), in which each and every account has its own page, on which all of the journal entries relating to that particular account are transcribed. With the GL you can look up an account such as Cash or Notes Payable or Salaries and see all of the transactions made during the year and the current balance of the account.

The Trial Balance

The process of closing out the books at the end of the year can be rather elaborate. There are often many adjusting entries to be made, and various accounts must be combined and fitted to form the final financial statements.

The first step in that process is the preparation of the Trial Balance (TB). The TB is a listing of all the accounts in the General Ledger with the current balances shown in either a debit or a credit column. Since debits and credits are equal in every transaction, the two columns of the trial balance should also be equal. Finding the two columns equal is the "trial" part, for if they are not, the accountants must locate and correct the errors before they can proceed. The accounts listed in the trial balance are then divided among the balance sheet and the income statement to form those reports.

The Mirror Image

To the neophyte, the discussion about debits and credits may contribute to some confusion and inconsistencies to the understanding of these two concepts. For example, when we say that a "debit to cash" adds to our cash balance, it can create understandable confusion. And when we put money into our checking account the teller, if he or she speaks to us at all, may tell us that the bank is crediting our account. But is this not debiting instead?

The confusion arises from the fact that our accounting entry in recording a transaction is often a mirror image of the other party's. The cash that we take in (our debit) is the same cash that the other person has paid out (his credit). And the goods we delivered to him are deducted (by a credit) from our balance sheet, and added (by a debit) to his. When the bank tells you that your deposit is being credited to your account, they are speaking from their viewpoint, not yours. Their accounting entry is:

| Dr | Cash |

| Cr | Demand deposits |

Since your demand deposit is a credit on their books, an entry crediting your account is one that increases the balance.

ACCRUAL BASIS OF ACCOUNTING

Accrual accounting has made us as dependent upon CPAs as we are on MDs and JDs. But if you want to know how much your business is really earning , it is the only way to go. First of all, accrual is hard to pronounce without sounding as if you had a mouth full of bubble gum. Even most accountants, who are steeped in reverence for the accrual basis, give the quick two-syllable pronunciation, "a-krool" rather than the proper three-step version, "a-kroo-al." Second, it rouses no sense of recognition or meaning. It is one of those words that requires you suspend all other thoughts while you struggle for its gist. And third, even when you remember that accrue means to accumulate or increase, it is still hard to make the connection with the accrual basis of accounting.

Now that that is out of my system, accrual is the accounting principle that counts sales as income even though the cash has not yet been received, and records expenses in the period they produced sales although they may have been paid in some other period.

If we look at the income statement in a company's annual report, the first item is sales, for the whole year, though it is likely the invoices from the final month are still uncollected. By the same token some expenses, such as telephone and utilities, are counted although those incurred in the last month may not be paid until the following year. Sometimes there is the opposite effect, where the cash moves first, and the recording of income and expense comes later. For example, a customer sends in a check along with an order; the check may be deposited right away, but no sale is recorded until the goods are delivered.

Or, say a company builds an elaborate display in December 2001 for a convention in January 2002. Assuming the company operates on a calendar year basis, the money spent in December would not be counted as an expense until 2002, the year in which the benefits of the expense are derived.

Accrual Basis versus Cash Basis

As individuals, most of us use a cash basis for tax purposes. We do not report money owed to us as income ” only the cash we have received. Nor do we take a deduction for a medical expense before we have paid the bill. Some businesses ” usually small ” operate that way, too. There are a few advantages. It is a clean and simple way of accounting; the cash receipts and payments records serve for the income and expense statement as well and for tax purposes. The cash basis allows some maneuvering through the use of delayed billing or accelerated payments. The big disadvantage of the cash basis is that it is a crude measure of a fast-paced activity ” so crude that a lot of damage can be done before a true assessment is made.

Details, Details

The accrual basis of accounting sometimes appears overly concerned with particulars. When the year ends one day after payday and an accountant spends hours calculating that one day's accrued salaries so they can be charged to the old year, you may well wonder if the accounting profession is not feathering its bed.

But if there is any one thing about business that is essential for management to know, it is an accurate picture of profit and loss. And given the large numbers we deal with and the slender profit margins that accompany them, getting accurate income figures is worth a lot of expense and bother.

Birth of the Balance Sheet

Accrual accounting is father to the balance sheet. Look at the assets side of a balance sheet, and draw a line under accounts receivable. Just about everything beneath that line is a prepaid expense, an expenditure waiting to take its place in the expense section of some future income statement.

On a cash basis, these assets would be counted as lost costs ” a gross distortion of the truth. But with accrual basis accounting we assign them a value commensurate with their potential for producing future revenue. The accrual method is often a pain both to apply and to understand, but consider the investment and credit decisions (and if those do not move you, the management bonuses) that are dependent upon it. The more accurate the measure of our past activities, the better will be our future decisions.

Profits versus Cash

Businesses are in business to make a profit, but they run on cash. And if you think I am kidding, try getting on a bus with just your income statement. Because accrual accounting distinguishes between the profit effect and the cash effect of transactions, it is necessary for management to have a cash plan as well as a profit plan. Yes, it is possible to be profitable and still go broke, that is, run out of cash. The problem can be acute for highly seasonal businesses or those with a fluctuating cash/credit sales mix.

Things are Measured in Money

Most annual reports begin with a hymn of praise by management for themselves, followed by colorful pictures of shiny products and smiling workers. It is the CPA's job to express all this in terms of dollars in the income statement and balance sheet.

From time to time, sentimentalists wonder why the human worth of the employees is not reflected on the financial statements. Most of us know workers who might qualify as assets, and others more properly described as liabilities, but no one has yet come up with an acceptable way of putting a number to these characteristics.

Values are Based on Historical Costs

The value of an asset is continually changing as a result of wear and tear on the one hand, inflation on the other. Perhaps the true value of an asset is revealed only at those moments in time when it is sold. Only at those times are we certain of the asset's hard cash value.

For convenience, accountants have fastened on the moment of acquisition to value the fixed assets. The amount originally paid for an asset is the balance sheet value, and no attempt is normally made to adjust that value except for scheduled depreciation.

For this convenience we pay a price, particularly in times of high inflation when assets often appreciate. One of the most often- heard criticisms of CPAs is their failure to value fixed assets at the current or replacement value. Leaving aside the controversy there are two things to keep in mind:

-

Most assets are difficult to appraise, and there is often a wide difference of opinion.

-

Business assets acquire value from the revenue stream they are able to produce. If the value of assets does indeed rise during inflation, the proof should be found in higher earnings.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 235