ISP Address Management Issues

| An ISP is in an unusual position when it comes to IP address space. Some of its addresses must be used to support internal operations. In this regard, an ISP's networking requirements can resemble an enterprise. However, the vast majority of an ISP's address space is allocated to servicing its customer base. Because we've already looked at address space management issues from an enterprise perspective, there's no need to rehash that here. Instead, let's acknowledge that similarities exist and then focus on the differences. Whenever an ISP gets a contract to provide Internet access to a new customer, one of the very first considerations that must be attended to is addressing. At this point in time, most end-user organizations have long since migrated to IP for their internal communication needs. Thus, they are likely to already be using IP and some type of IP addressing. The real issue is whether that network address block can also be used for Internet access. An ISP might find itself having to support IP addressing on behalf of its customers in at least three primary ways:

Unfortunately, an ISP can't just arbitrarily select one of these options and use it exclusively. Instead, an ISP is likely to have to support all of these options. The issue of address block ownership can become quite muddled over time. The fact that IETF and IANA have shifted their policies in the past decade with respect to this issue has exacerbated an already unclear issue. We'll look at each approach to address space management for an ISP, as well as their respective implications and consequences. Assigning Address Space from InventoryAn ISP's business is to provide connectivity to the Internet via IP. Thus, it is essential that an ISP ensure that new customers have a block of IP addresses that they can use to connect to the Internet. One of the means by which this is done is to temporarily assign each new customer a block of addresses carved from a much larger block that is directly registered to the ISP. For example, if the ISP has a /16 network block, it has enough addresses to identify 2 to the 16th (65,535) unique endpoints. Such a block becomes, in effect, part of the ISP's business inventory. When an ISP grants a customer temporary use of part of its own address space, that space remains registered (in the eyes of the regional registrars, IANA, and so on) to the ISP. Yet there would be great value in being able to identify the party to whom that CIDR block was assigned. The traditional way of discovering to whom an address block is assigned is via the whois command. In the case of an ISP's address space, that space would be registered to the ISP, but it can be subassigned to other organizations in small pieces. This is where the Shared WhoIs Project (SWIP) becomes useful. When an ISP SWIPs an address block to the customer, the ISP remains the only entity that can further modify that SWIP. SWIPing a network address lets an ISP identify to the Internet community which end-user organization is using which CIDR block from its address space. Of course, the other way of looking at this is that SWIPing helps registries ensure that blocks assigned to ISPs are being used correctly. Assignments from an ISP address block are temporary. The termination date should be set in the service contract that is signed between customer and ISP. The terms and conditions of such contracts likely ensure compliance with RFC 2050. It is imperative that an ISP have procedures in place to ensure that its hostmaster is tightly tied to its service delivery function. This allows the hostmaster to both allocate blocks to new customers as needed and reclaim blocks previously assigned to customers that have left. RFC 2050An ISP is awkwardly positioned: It must balance efforts to satisfy customers with operational mandates from the IETF, IANA, and others designed to ensure the viability and stability of the Internet and its address space. Unfortunately, those mandates sometimes are diametrically opposed to what customers want! Stated more simply, an ISP is charged with maintaining an address space's integrity. It uses that address space to provide service to customers. Customers get used to using an address space, and they assume that they "own" it. Such is the life of a hostmaster at an ISP. We discussed the ramifications of RFC 2050 in Chapter 5, "The Date of Doom." Prior to the publication of that document (which subsequently was embraced as Best Current Practice #12), ISPs were at liberty to regard the address space registered to them as portable. In other words, blocks assigned to specific customers from the ISP's block could be interpreted as being the property of that customer. Thus, when the contract for service ended, customers of some ISPs simply took "their" address block with them. This had the undesirable effect of poking permanent holes in larger blocks. The second problem was that the ex-customer's new ISP had to support its network address, which drove up the number of total routing table entries across the Internet. Thus, address space portability was deemed undesirable. RFC 2050 effectively ended the mythical claims of portability by declaring that address space registered to ISPs should remain under their charge. ISP customers may be assigned a block of addresses, but both parties should regard that assignment as a lease. When the service contract terminates, the addresses are to be returned to the ISP. This created an interesting problem for ISP customers. Addresses get implemented in a stunning variety of locations: on desktops and laptops, servers, and network interfaces. These are all fairly obvious places for an IP address to be configured. But addresses might also get hard-coded in applications and scripts. The point is that changing IP addresses is an extremely onerous task. They might get configured on a finite number of devices, but they can get reinforced in a seemingly infinite array of other places. Renumbering is sure to be a costly and risky endeavor. Thus, customers that have made the mistake of directly configuring an address space provided by an ISP will stubbornly resist any and all attempts to force them to renumber! Supporting Foreign AddressesA foreign address is one that is not native to a networked environment. There are four scenarios in which a customer can approach an ISP and request that it support a route for its network block even though that block is registered to another ISP:

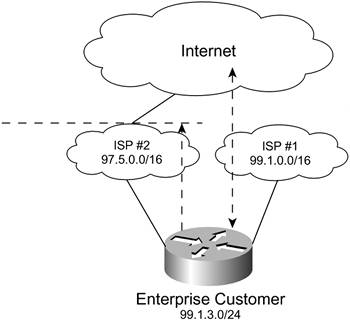

Each is similar in that an ISP is being asked to support a foreign route. However, the implications of each scenario are remarkably different. Thus, we'll examine them individually. Using Directly Registered AddressesSome Internet users are fortunate enough to have their own address space that's directly registered to them. When I say directly registered, I mean just that: They applied for their own address space with their regional registrar. Only directly registered network blocks are considered portable. That is, they are registered to an end-user organization, and that organization may continue to use that network block regardless of which ISP they use for connectivity to and from the Internet. Although directly registered network addresses might sound like the ideal solution, you should recognize that the Internet's standards and policies are a moving target. What once was considered globally routable may now, in fact, not be! Without going into too much detail about how ISPs set policy regarding how long or short of a network prefix they will support, suffice it to say that any network prefix that isn't a /20 or larger runs the risk of not being supported globally across the Internet. To better appreciate this point, consider Figure 13-3. The dotted lines indicate the limits of the likely reachability of that customer's directly registered network address. Figure 13-3. A Customer with a Directly Registered /24 Network Address Block Might Find Its Reachability Limited Across the Internet

In this figure, a customer with its own /24 network address space purchases Internet access from a second-tier ISP. This ISP ensures that its customers enjoy broad reachability by purchasing transit service from two Tier 1 ISPs. Both of these ISPs, however, are very concerned about the size of their routing tables and refuse to accept any network prefix longer than a /20. This limits the reachability of the customer's /24 to just its immediate upstream ISP. Thus, an organization with its own directly registered /24 (Class C) network might someday have to accept the fact that its network address isn't being communicated across some ISP networks. When that happens, some tough choices will have to be made. Although this might sound like a far-fetched example, it isn't as outrageous as you might think. Fortunately, most ISPs are willing to discuss exceptions to their policies on a case-by-case basis. Dual-Homed CustomerA dual-homed ISP customer is one that connects to two different ISPs. Such redundant connectivity affords the customer an added measure of fault tolerance. Figure 13-4 shows the general topology of a dual-homed ISP customer, including the implications of supporting a "foreign" route. The route is considered foreign for two reasons. First, it isn't native to ISP #2. Second, it is part of an address block registered to ISP #1. This puts ISP #2 in the position of having to advertise a valid route for someone else's address space! Figure 13-4. A Dual-Homed Internet Customer Requires ISP #2 to Accept a Foreign Route

Although this practice is becoming increasingly common among end-user organizations that require a fault-tolerant connection to the Internet, it threatens to obsolete many long-standing practices that assume single-connected end-user organizations. We looked at one such practice, known as Source Address Assurance, in Chapter 12, "Network Stability." Stolen Address BlockCustomers that refuse to part with an address block that was assigned to them by a former ISP sometimes insist that their new ISP accept that block as a precondition to signing a contract with them for service. Although such a precondition seldom makes its way into writing, it isn't uncommon for this to be discussed between customer and sales representative during presale negotiations. Other times, the customer may make no representation other than that it does not need a block of addresses from its new supplier, because it already has one. Regardless of how it happens, the net effect is the same: The new ISP must accept and advertise a route for a network block created from someone else's address space. This practice defies aggregation of prefixes, because it is highly likely that the spurious network prefix is not even mathematically close to the ISP's addresses. It also has the undesirable effect of increasing the number of routes that must be supported across the Internet. "Made-Up" Address BlockAnother circumstance can put an ISP in the unenviable position of supporting routes for someone else's address space. Vast portions of the IPv4 address space remain unassigned. Some companies have been known to simply implement a block of addresses from an unassigned range. That would almost make sense if that company required only internal IP connectivity and had no intention of ever connecting to the Internet. Over time, however, requirements canand dochange. Thus, a company could find itself having to renumber its endpoints if it lacked foresight when it first implemented IP. ISPs should never support an address space that a customer does not have a legitimate claim to use! Although this is a slightly more benign behavior (more ignorant than larcenous), it still results in the same net effect: an ISP's being asked to support a route for an address block that does not rightfully belong to its customer. The only way for an ISP to ensure that it is not supporting a squatter's rights to an unassigned address block is to query ARIN's (or RIPE or APNIC, depending on geography) whois database before agreeing to support the customer's network block. What Does It Mean?The bottom line is that an ISP is likely to have to support routes for an assortment of network addresses. Some of those blocks are created from that ISP's larger blocks, and others are foreign to it. The network blocks it must support tend to be relatively large. The important thing to realize is that the operational issues an ISP faces are just a different aspect of the same challenges facing Internet hosting centers (discussed next) and end-user organizations. Unless you are using IP and you do not connect to the Internet for any reason, you will likely encounter these challenges from one or more perspectives. |

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 118