The Rules of CAN-SPAM

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

To fully understand the CAN-SPAM Act, you need to know why it was created and what it is intended to achieve. CAN-SPAM is a method to help protect and maintain the integrity of e-mail, which has grown into possibly the most critical form of communication to any company or country. The use of e-mail has developed into the largest form of electronic communication. Spam is seen as a destructive and counter-productive element that by its sheer size and volume could threaten the state of global communications. How would companies cope if they could no longer rely on e-mail for communication? The possibility of rogue Chinese spammers bringing down the United States’ primary form of communication seems to have most U.S. senators very concerned, since many of them didn’t hesitate to support CAN-SPAM. U.S. Senator Charles Schumer of New York said the following at the 2004 Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Spam Summit:

As you are all aware, spam traffic is growing at a geometric rate, causing the Superhighway to enter a state of virtual gridlock. What was a simple annoyance last year has become a major concern this year and could cripple one of the greatest inventions of the 20th century next year if nothing is done.

The following snippet from the act shows the reasoning and ideas the U.S. government used to create the law:

The convenience and efficiency of electronic mail are threatened by the extremely rapid growth in the volume of unsolicited commercial electronic mail. Unsolicited commercial electronic mail is currently estimated to account for over half of all electronic mail traffic, up from an estimated 7 percent in 2001, and the volume continues to rise. Most of these messages are fraudulent or deceptive in one or more respects.

A key aspect of CAN-SPAM is the “Non-Solicited” section, which effectively states that any marketing, promotional, or sales-related electronic communication requires a prior consent on the recipient’s part. If your e-mail address is transferred to another party, that party will need to gain your consent before you are legally able to send any marketing or sales related communication. Additionally, you will need to tell each recipient that their contact details are being sold or transferred to another party. This is an attempt to inhibit the rapid and unsolicited trade of e-mail addresses between spammers. Here is a relevant snippet from the exact section of CAN-SPAM:

(A) the recipient expressly consented to receive the message, either in response to a clear and conspicuous request for such consent or at the recipient’s own initiative; and

(B) if the message is from a party other than the party to which the recipient communicated such consent, the recipient was given clear and conspicuous notice at the time the consent was communicated that the recipient’s electronic mail address could be transferred to such other party for the purpose of initiating commercial electronic mail messages.

| Notes from the Underground ... | Free Speech? In a nation based on free speech principles, the idea behind CAN-SPAM is highly controlling in nature. CAN-SPAM stands for inhibiting any method of selling a product or service via e-mail, unless the recipient explicitly desires to hear the sales pitch. But why is e-mail the exception to the sales pitches we are subjected to every day? TV, radio, and billboards force your mind to be influenced by various advertising gimmicks, even though you might not desire any such communication from the sponsoring company—you simply have no choice. Is e-mail treated differently because spammers are not backed by expensive, powerful corporations? Is the driving reason behind banning spam simply that spammers do not pay money to the government, in the form of taxes? Why is the entrepreneurial spirit being crushed from the common man? Whether you endorse the use of spam or not, these questions should be considered, if merely from the standpoint of considering the undertones that are affecting the decisions being made. |

CAN-SPAM also attempts to identify possible illegal methods used to send spam; many of the common methods used today are now considered illegal and can result in jail time for the abuser. If you use any method to hide, obfuscate, or mislead recipients regarding the origin of your e-mail, you are breaking the law, whether you’re using a proxy server or insecure SMTP relay or injecting false header information.

The mail-sending host is now legally required to be responsible for all e-mail it sends and can in no way attempt to hide or obfuscate its true locality. Spammers are notorious for keeping their private information private, especially when sending spam, and this section of CAN-SPAM targets just this characteristic. Unless you are willing to disclose who you are when you send e-mail, you are breaking the law. This section of the CAN-SPAM Act has caught many spammers so far, as you will see later in this chapter. A shortened version of the exact text from the act is as follows:

(1) accesses a protected computer without authorization, and intentionally initiates the transmission of multiple commercial electronic mail messages from or through such computer,

(2) uses a protected computer to relay or retransmit multiple commercial electronic mail messages, with the intent to deceive or mislead recipients, or any Internet access service, as to the origin of such messages,

(3) materially falsifies header information in multiple commercial electronic mail messages and intentionally initiates the transmission of such messages,

(4) registers, using information that materially falsifies the identity of the actual registrant, for 5 or more electronic mail accounts or online user accounts or 2 or more domain names, and intentionally initiates the transmission of multiple commercial electronic mail messages from any combination of such accounts or domain names, or

(5) falsely represents oneself to be the registrant or the legitimate successor in interest to the registrant of 5 or more Internet protocol addresses, and intentionally initiates the transmission of multiple commercial electronic mail messages from such addresses ...

CAN-SPAM also focuses on the ability to opt out of an existing e-mail list. Failure to provide a valid opt-out address in your e-mail is now also punishable by law. Once a recipient has agreed to accept your marketing or sales-related e-mails, you need to provide an option for them to discontinue receiving your messages. Senders must honor the recipients’ request for removal and discontinue sending them any e-mail correspondence, until the recipient explicitly signs up for the service again and gives direct approval for e-mail communication.

Interestingly, another listed item in the CAN-SPAM Act has been drawing some attention of late: under Section 5, Paragraph A, subsection 5(iii), which defines what an e-mail requires to be compliant with CAN-SPAM. The law states that “a valid physical postal address of the sender” is required in each sales or marketing e-mail sent. In other words, spammers now are required to give a valid postal address if they want to be compliant with the act. This is a very interesting addition—an attempt to make spammers disclose their full contact information, making them more responsible for the messages they send. However, it has obvious flaws in its effectiveness. A spammer can be fully compliant with the act by having a valid P.O. box set up in Nigeria or Nicaragua and use that address as their own on every spam e-mail they send.

Although a spammer may be physically located in Germany and sends his spam through a server located in Japan, if he sends mail to any address in the United States, he must obey the U.S. CAN-SPAM Act. Extradition cases are not unheard of, and if your spamming activities are prolific enough that federal authorities take notice of you, extradition may be a reality—or you could even find yourself arrested if you ever try to enter the United States.

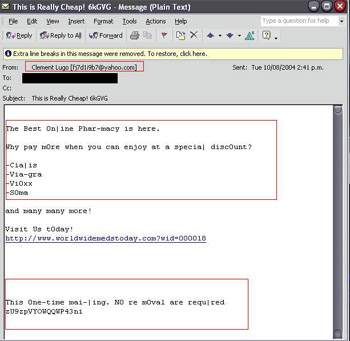

CAN-SPAM also goes into detail about the contents that the body of a spam message can contain. Any spam filter evasion technique is now effectively illegal. Additionally, any method used to socially mislead or misinform the recipient about the e-mail’s true nature is also forbidden in the eyes of the law. Spam needs to be direct, to the point, and clearly identifiable, containing no random data or false links. Honesty is the only attribute that will redeem e-mail, and any attempt to be dishonest about the e-mail’s content or nature will most likely result in you breaching the terms of the CAN-SPAM Act. I receive many spam e-mails; Figure 10.1 shows an example of a misleading message.

Figure 10.1: A Misleading “Phar-macy” Message

Each highlighted section of Figure 10.1 is an example of misleading content. First, the reply e-mail address at yahoo.com is fake; this e-mail did not originate from the Yahoo! network. The message body also contains misleading text—mispunctuated words such as On|ine, Phar-macy, and Via-gra. These words are not misleading to the human eye, but they are misleading to any computer or spam filter, and they have been placed in this spam solely for this purpose.

The lack of a method to opt out and the promise that this spam is a “One-time mail-|ing” have ensured that this spam breaks almost every section of the CAN-SPAM Act. It also fails to provide a legitimate postal address of the originating company. This spammer, if caught, is looking at a very costly fine or possibly jail time.

Punishable by Law: What Are the Repercussions?

Let’s say that you’re a U.S. citizen and you have been making a living sending millions of unsolicited e-mails for the past three years. You have never given your recipients any method of opting out of your mailings, and you regularly send your spam through open proxy servers and Botnets. You’ve injected misleading headers to confuse your recipients and have used other filter evasion techniques to ensure maximum delivery. In short, you’ve used all the tricks of the trade.

You have the mindset to “use what works,” and since your spam works well, you have grossed over $400,000—a tidy profit for any self-employed marketer. However, one day the police knock on your door and ask you to accompany them to the station. Apparently you are a notorious spammer and are now looking at extensive fines and possible jail time under the new CAN-SPAM Act. But just what is the punishment for sending spam? Illicit spammers can incur very costly fines if lawsuits are brought against them. The following is the section of the CAN-SPAM Act that covers the amounts of damages and costs to spammers who are brought to court:

(A) IN GENERAL—For purposes of paragraph (1)(B)(ii), the amount determined under this paragraph is the amount calculated by multiplying the number of violations (with each separately addressed unlawful message received by or addressed to such residents treated as a separate violation) by up to $250.

(B) LIMITATION—For any violation of section 5 (other than section 5(a)(1)), the amount determined under subparagraph (A) may not exceed $2,000,000.

(C) AGGRAVATED DAMAGES—The court may increase a damage award to an amount equal to not more than three times the amount otherwise available under this paragraph if—

(i) the court determines that the defendant committed the violation willfully and knowingly; or

(ii) the defendant’s unlawful activity included one or more of the aggravating violations set forth in section 5(b).

(D) REDUCTION OF DAMAGES—In assessing damages under subparagraph (A), the court may consider whether—

(i) the defendant has established and implemented, with due care, commercially reasonable practices and procedures to effectively prevent such violations; or

(ii) the violation occurred despite commercially reasonable efforts to maintain compliance with such practices and procedures. …

(g) Action by Provider of Internet Access Service—

(1) ACTION AUTHORIZED—A provider of Internet access service adversely affected by a violation of section 5(a) or of section 5(b), or a pattern or practice that violated paragraph (2), (3), (4), or (5) of section 5(a), may bring a civil action in any district court of the United States with jurisdiction over the defendant—

(A) to enjoin further violation by the defendant; or

(B) to recover damages in an amount equal to the greater of—

(i) actual monetary loss incurred by the provider of Internet access service as a result of such violation; or

(ii) the amount determined under paragraph (3).

As you can see, the cost can be highly significant, depending on the nature of the spam. If the spam tried to mislead the recipient and the spammer was fully aware and conscious of his actions to do so, he would be facing a very serious fine or possibly jail time. Legally, spammers can now face up to a $2 million fine and/ or up to five years in jail, depending on the characteristics of the spam and the spammer. If the spam also broke other sections of the CAN-SPAM Act or the spammer was aware he was breaking the law by sending spam, the fine can triple up to $6 million. Six million dollars for sending spam is nothing to laugh at and shows just how serious the authorities are when it comes to stopping spam and spammers.

| Notes from the Underground ... | Spam: Hard Copy vs. Electronic Is the global, antispam sentiment any different from the “No Circulars” sticker stuck to my mailbox outside my house? Every day flyers and promotional material are stuffed into my mailbox, despite the fact I obviously do not want to receive them. If this were my e-mail inbox, I could sue the company that printed the flyer and the post-boy who delivered it, for $250 per piece of promotional data. Possibly my delivery boy would face jail time, since I did not give any direct consent to receive any promotional material and I visually expressed my desire not to receive such information. Why are electronic messages treated differently from spam? Spam e-mails are identical to the flyers for pizza, fried chicken, and discount clothes I receive daily. Quite possibility, spam is less harmful than these flyers, since the spam I sent never hurt a single tree and had no impact on our environment, and it certainly will not still be degrading in a landfill 50 years from now. So why is the punishment greater for sending spam, and why can’t I sue my delivery boy? |

However, for all intents of the act, law enforcement agencies lack the resources and time to hunt down the millions of spammers in the world. So far, the majority of legal cases brought against spammers have been filed by private companies, Internet service providers (ISPs), and product vendors that suffer huge annual losses associated with spammers and spam. Such companies can afford to have dedicated teams of spam hunters. These new-age private investigators focus solely on tracking and catching notorious spammers. Once enough information has been gained and the spammer’s true identity is established, either a criminal complaint is filed or the company sues for damages associated with the spammer’s activity. Spam may be a profitable business for spammers, but for many ISPs, spam costs millions of dollars each year in bandwidth and storage costs, and companies are becoming more aggressive about getting compensation for these costs associated with spam.

Although the maximum fine you can receive under the CAN-SPAM Act is $6 million (for an aggravated violation), if the spam contained false or deceptive headers, there is no maximum fine limit. Each message sent will instead receive a fine of $250; 10 million spam messages containing falsified headers would result in a fine of $25,000,000,000 (that’s $25 billion). Perhaps this is slightly overkill for spam, but it does send a very strong message.

The Sexually Explicit Act

On May 19, 2004, a much less publicized act, known as the Label for E-mail Messages Containing Sexually Oriented Material Act, came into effect. You can read the full text of the act at www.ftc.gov/os/2004/04/040413adultemailfinalrule.pdf .

Unlike CAN-SPAM, the Sexually Explicit Act, spurred by concerned parents, focuses solely on pornographic content within spam and attempts to clearly define prohibited content, although this act is reiterated in the CAN-SPAM text. The practice of including acts of sexuality in unsolicited e-mail is now an offense that carries the same fine as breaches of the CAN-SPAM Act. Sexual content is defined as follows:

… sexual intercourse, including genital-genital, oral-genital, anal-genital, or oral-anal, whether between persons of the same or opposite sex; bestiality; masturbation; sadistic or masochistic abuse; or lascivious exhibition of the genitals or pubic area of any person.

Legally, if the majority of the body of an unsolicited e-mail contains such material, the subject line is required to be prefixed Sexually Explicit or Sexually Explicit Content. This way, the e-mail can be easily identified and either deleted by the recipient or automatically filtered by any spam filter.

Obviously, crude content will require the words Sexually Explicit in the subject line, to be compliant with this act; hardcore pornographic images simply cannot be used in spam anymore, unless you are willing to tell the recipient and any spam filter that the message is spam. However, if you think creatively about the images and messages you use, you can work your way around this act and find ways to get your message across without being obviously crude.

For example, if I sent spam containing a picture of an attractive brunette wearing a seductive nurse’s uniform, above a catchy phrase like “Will you be my doctor?”, this content is legally not sexually explicit, although it will get across the more subversive message.

The definition of sexually explicit content clearly excludes any sexual products or devices, making adult toys legally not sexually explicit material, given that no one is currently using them for sexual pleasure in the picture. The nurse in our example could easily be holding a sexual device and I would not be required to label the spam sexually explicit, since such content is seen on TV all the time.

Senators were pressured to implement the Sexually Explicit Act by parents and child activists, since pornographic e-mails do not usually contain pornographic subject lines or text that can easily identify them and can subsequently deceive the reader as to the e-mail’s true nature. As shown previously in this book, spam filters actively filter content that is of pornographic nature, so the majority of pornographic spam will contain a misleading or obscure subject to evade content-based spam filters, often fooling the recipient into opening the message body, where they become bombarded with offensive graphics and offers for pornographic Web sites. The act was rushed into passage when statistics showed that children under the age of 18 received an average of 20 pornographic spam e-mails a day.

| Notes from the Underground ... | Free Speech, Part Two To be compliant with the act, all spammers need to declare that their messages are spam. Many spam filters already filter any message with Sexually Explicit in the subject line, and many spammers refuse to be compliant with this act if it means 80 percent of their e-mails will be filtered and they will end up losing business. The act is over-critical, in my opinion, and inhibits free speech—one feature the Internet actively promotes. |

A recent study by Vircom (www.vircom.com/Press/press2004-06-02.asp), developers of e-mail security software, found that less than 15 percent of pornographic spam is compliant with the Sexually Explicit Act of 2004. Over a two-week period, Vircom analyzed over 300,000 pornographic e-mails that contained sexually explicit content that should have been classified as Sexually Explicit, under the newly passed act. Vircom found that only 14.72 percent of the e-mails possessed the required Sexually Explicit prefixed subject line and were in accordance with the law; the remainder featured obscure or deceiving subject lines and no indicators of their true sexual nature. Vircom went on to interview a spammer who exclusively distributes sexually oriented material; the spammer was asked why he chose to not comply with the recent addition to the law. He said:

If I write Sexually Explicit in the header, I can guarantee that none of my e-mails will make it through a spam filter. In fact, it won’t even make it through Outlook rules … You might as well kiss your job goodbye.

For many spammers, if they have to choose between being legally complaint and making a profit, the profit will win.

The Do-Not-E-Mail Registry

Under Section 9 of the CAN-SPAM Act sits the guidelines for the do-not-e-mail registry, an attractive idea similar to the “Do not call” registry required of telephone marketers. The purpose of such a list is to maintain a database of e-mail addresses of users who do not want to receive unsolicited e-mail. All spammers would be obligated to obey such a list, sending spam only to those who are not listed in the database.

When I first read this section of the CAN-SPAM Act, I doubted how successful it would be; a spammer would never obey a do-not-spam registry. As I’ve mentioned throughout the book, spammers do not actually care if you don’t want to receive their spam. They figure, if you get an e-mail you don’t want, just delete it. Section 9 of the CAN-SPAM Act details the plans for this registry, partially listed here:

SEC.9. DO-NOT-E-MAIL REGISTRY.

(a) IN GENERAL—Not later than 6 months after the date of enactment of this Act, the Commission shall transmit to the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation and the House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce a report that—

(1) sets forth a plan and timetable for establishing a nationwide marketing Do-Not-E-Mail registry;

(2) includes an explanation of any practical, technical, security, privacy, enforceability, or other concerns that the Commission has regarding such a registry; and

(3) includes an explanation of how the registry would be applied with respect to children with e-mail accounts.

(b) AUTHORIZATION TO IMPLEMENT—The Commission may establish and implement the plan, but not earlier than 9 months after the date of enactment of this Act.

The task set forth in this clause is humongous, even considering only U.S.-based e-mail addresses; most American adults have at least two e-mail accounts—usually one for work, another for personal e-mail, and possibly a third that is under-used or from a legacy mail server. To administer and update a database containing so many e-mail addresses would be a highly complex and tedious task. Such a database would easily be the largest in the world, and it’s easy to imagine how rapidly it would grow. With an estimated 273,706,064 Americans on the Internet, if each user has three e-mail accounts, you would need to store 821,118,192 records, not to mention the complications of continuous growth of the Internet and increasing numbers of new users. Internet user figures grow 30 percent annually, and if a do-not-e-mail registry became implemented globally, you would be required to store 2,400,121,494 (2.4 billion) e-mail addresses—a figure that would grow 30 percent annually. Not only is the idea of a central registry bewilderingly complex, but it offers a very circuitous way of trying to solve the spam problem, and its number-one flaw is that it relies on spammers being honest.

If a spammer is willing to steal your e-mail address from a newsletter you subscribe to and intends to send you Viagra spam containing deceptive mail headers, why do you think he would bother to obey a do-not-e-mail registry? The spammer’s already broken the law twice—why stop now? Spammers would never obey such a registry, and the list itself would become a very large target to obtain—if the spammer could find a way to steal 2.4 billion valid e-mail addresses, he would be a very rich man, so it would be well worth his time to try.

Surprisingly enough, on June 15, 2004, the FTC rejected the idea of a do-not-spam registry, calling it unmanageable and a “waste of time.” It was clearly identified that the majority of spammers would never honor such a registry. It was also acknowledged that the list would become a target for hackers and spammers, since each e-mail address in the registry would be a verified, legitimate address—in other words, pure digital gold. Some U.S. senators were unhappy with this decision. Senator Charles Schumer strongly suggested that Congress implement the national registry and was the driving force behind the idea. He said:

We are very disappointed that the FTC is refusing to move forward on the do-not-e-mail registry; the registry is not the perfect solution, but it is the best solution we have to the growing problem of spam, and we will pursue congressional alternatives in light of the FTC’s adamancy …. As for the FTC’s concerns that such a list would not work, the FTC had years being dissatisfied at the newly implemented do-not-call list, but when they finally implemented it, it was an overwhelming success.

On the other hand, Timothy Muris, FTC chairman, had the following comment:

Consumers will be spammed if we do a registry and spammed if we don’t.

Instead of designing a do-not-spam registry, the FTC has decided to push the private sector to establish a method of electronically authenticating e-mail servers and holding mail servers accountable for the mail that they send. In short, this technology is Sender-ID and SPF, which the FTC hopes will subdue the torrents of spam that are currently pumped into the Internet.

| Notes from the Underground ... | SPF and Sender-ID SPF and Sender-ID are not perfect ideas; in theory, both are greatly flawed and are still highly exploitable by spammers. Alternatively, they have much more stability and credibility than a central registry and are by far the smarter solution to filtering spam. |

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 79