Types of Attacks: The New Age Battle Ground

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

Types of Attacks: The New Age Battle Ground

Work From Home, Make large money doing nothing!

Have you ever seen flyers attached to lampposts that offer an easy and effortless way to make large amounts of money working from home? The job sounds appealing, but unfortunately, these flyers are almost always fake or misleading. I call these types of frauds “mule makers,” behind which the idea is simple. Within these jobs, you work from home running a forwarding service for either money coming into your bank account, or packages arriving on your doorstep. You earn a small percentage fee for each item you forward; the scammer gives strict instructions of when a package or deposit will be made, and your job is to quickly repackage and send the goods to another address. These addresses are often in Russia, China, or Taiwan, which is strange, but because you actually get paid for your efforts, you probably won’t ask too many questions. I have heard several stories of people who made several hundred dollars from this method, and even though this is not enough to live off of, it is still some income. The only problem occurs when the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) knocks on your door and asks why you are receiving stolen funds and goods, and where the goods are now.

This particular scam turns hard working homemakers into human proxy servers, a convenient method of hiding the identity of the true scammer who is pulling the strings behind the innocent workers. If someone has 1,000 valid credit cards and they want to order a laptop, what is the best way for them to do this? Due to the high risk of fraud, companies do not send expensive items such as laptops to P.O. boxes and usually require the delivery address to be a residential or commercial address, something that has a certain level of accountability and credibility. Therefore, scammers find someone who has those things; a hardworking homemaker who is unable to work a traditional full-time job is the perfect target. The job requires accepting courier parcels that arrive on set dates, rewrapping the package in brown paper, and sending it to a P.O. box in Russia. The scammer provides a false story about being an online shop vendor who is unable to send packages directly to Russia due to its economic strife. In return for their hard work, the worker is allowed to keep some of the packages gratis.

After a month, 10 or 15 packages may be processed, containing large, expensive products from online computer stores and high-end clothing chains. The scam goes without a hitch until credit card companies identify many similar fraudulent transactions and decide to investigate. At that point, the FBI is informed and it doesn’t take long until the homemaker’s address is the common factor among all the orders. The homemaker is instantly the suspect and raided by the FBI.

This unsuspecting person is dubbed a mule, an unwilling party that is pulling most of the weight of the entire illegal operation without any idea of what they are really involved in. The scams take many forms, from repacking and posting expensive goods to accepting bank deposits and transferring amounts to other accounts. Scam pitches are always the same, though: work from home and make large amounts of money doing almost nothing. An effortlessly rewarding occupation tends to draw attention from the same type of person: the average Joe who is in financial trouble, either unemployed or stretched for money.

The majority of these scams come from Russia and other parts of Eastern Europe. The address or account the merchandise is forwarded to is often another mule until the product is sent to an anonymous P.O. box or an abandoned house in an isolated, rural part of town. This allows the products to be moved quickly around the world, increasing the paper trail and hiding the scammer’s identity. It also acts as a highly profitable defrauding system; once wiped of all ownership marks, the goods can be sold for local currency with little chance of the scammer being caught. However, the mule is often arrested and has a hard time explaining the difficult plot to police. Mule scams have been around for years and the scam is always the same, but the Internet has allowed scammers to become global, reaching millions of potential victims via the Internet, turning this scam into one of the most commonly found on the internet.

Phishing for Bank Accounts and Credit Cards

If you received an urgent e-mail from your bank requesting that you verify your account status, what would you do? Hopefully, you would first ask why the bank needed verification and then question why they would send an e-mail about a matter so important. What would happen if you ignored the e-mail? Would it be better to be safe and do what it says? The choice is even harder when you are inexperienced with the Internet and online banking. An e-mail asking you to verify personal information by giving details of your finances is a classic example of an online phishing scam. The scammer has created a cunning way to profit by fooling recipients into thinking their online account may be revoked if they don’t act right away; the user is mentally rushed and often forced into disclosing highly confidential information. The two most sought after pieces of information are online bank account details and credit card numbers, which are then used to siphon funds out of accounts, usually destined for a remote third world country. Other similar phishing attempts have been known to target eBay accounts and stock trading accounts, looking for any account information that can be used to steal money directly, or to impersonate a user with the intention of stealing money from other users.

| Notes from the Underground… | Phishing This type of scam is highly common. Earlier this year I received a distressing call from my girlfriend, who informed me that someone had stolen $10,000.00 from her bank account. Highly shocked that this happened to someone so close to me, I instantly began helping her with tracking the money and the path it followed. Someone had obtained her bank login and password and transferred $10,000.00 into another local bank account. I called her bank and asked what bank the destined account number belonged to. I was shocked to find that it was a bank in the same state. It was obvious that this would prove to be too trivial for law enforcement to track down; the only catch was that the money recipient was not the thief but an unaware mule who had been asked to receive deposits and forward the balances to another account. “K. Anderson” had become an unwitting party in the money stealing game and was earning a percentage of all money he accepted and transferred. The final destination for the money was in Latvia of all places. Once the bank was sure the money was fraudulently taken, they covered the loss with insurance and gave my girlfriend back her money. She swore she would never use the Internet again for online banking and since then has become very weary of technology. We were not told what happened to K. Anderson, but there is a high chance he was prosecuted for receiving stolen funds or transferring stolen money. |

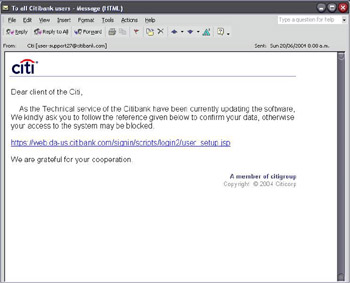

So what does a typical bank phishing scam look like? Figure 9.1 shows an example scam that apparently came from “CitiBank.”

Figure 9.1: Calling All Citibank Users

Dear client of the Citi? This sounds suspicious already. The following shows the Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) source of this scam:

<html><p><font face="Arial"><A HREF="https://web.da- us.citibank.com/signin/scripts/Iogin2/user_setup.jsp"><map name="FPMap0"><area coords="0, 0, 610, 275" shape="rect" href="http://%36%38%2E%32%32%35%2E%34%34%2E%32%35%31:%34%39%30%33/%63%69 %74/%69%6E%64%65%78%2E%68%74%6D"></map><img src="/books/3/175/1/html/2/cid:part1.00080301.07030904@users-billing42@citibank.com" border="0" usemap="#FPMap0"></A></a></font></p><p><font color="#FFFFF9">NCAA Basketball Peterson case where do you live? in 1885 in 1873 </font></p></html>

Scam spams use the exact same obfuscation techniques previously discussed in this book and we can identify some clear methods used in this spam.

The body of the e-mail contains very little textual data. The majority of the body text comes from a picture included via HTML. HTML is very versatile; you can see from the Image (IMG) tag that it includes the body picture and the image using its Content ID (CID) cid:part1.00080301.07030904@users-billing42@citibank.com. This includes the first attachment that came with the e-mail that happens to be a picture of the body text. Obviously, this is a filter evasion technique. Banks do not send out e-mails asking clients to renew or verify their accounts; filters will have few false positives by blindly discarding all bank verification e-mails. The scammer knows this and has hidden the body of the scam in a picture. Additionally, this scammer has tried to not be so obvious about hiding the body text and has avoided using a direct IMG SRC= tag from a remote host, choosing in its place the less-filtered CID tag, often used when displaying attached pictures or logos from an e-mail.

The next interesting part of this deception is the highly obvious legitimate Hypertext Reference (HREF) at the top of the e-mail, just after the opening HTML tag, <A HREF=”https://web.da-us.citibank.com/signin/scripts/Iogin2/user_setup.jsp”>. Although Login is misspelled as “Iogin,” the host looks remarkably correct. If you glanced at the HTML source you would probably think that this is a legitimate e-mail.

This scammer uses a very deceptive technique; tricking the user into thinking they are clicking on the correct Uniform Resource Locator (URL). Inside the source of the HTML is an area coordinates directive. This directive draws a square onto the page (the dimensions shown are 0, 0, 610, and 275). This square acts as a hidden “hotlink” area and has its own link associated to it. Area coordinates take precedent over existing HREF links (think of them as a layer on top of the e-mail). Therefore, the first HREF at the top of the e-mail does nothing; it is purely aesthetic and is there just in case someone glances at the HTML source. Notice how HREF is highly visible in all caps. This may make you think that you don’t need to read the e-mail further because you know where it links to; however, if you click anywhere within coordinates 0, 0, 610, and 275 (which happen to be anywhere on the included image) you will go to a very different site. The Web site http://%36%38%2e%32%32%35%2e%34%34%2e%32%35%31:34/%63%69%74/%69%6E%64%65%78%2E%68%74%6D included in the area cords is actually http://68.225.44.251:34/cit/index.htm, which is encoded in hexadecimal (hex encoding is shown by the prefix %). At the center of this scam is the Web site, which features an identical layout to Citibank’s real Web site and requires your username and password. Once you enter any account information you are directed to a Web site thanking you.

If you’re interested in encoding or decoding data, the Web site www.gulftech.org/tools/sneak.php converts American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) to hex and vise versa. There are many other encoding types that can be used that this Web site will easily convert.

The scammer now has your bank details and it is easy for them to move money out of your account. Bank balances at the same bank are often harvested into one large account, and usually contain a history of moving large balances of money. So as to not look suspicious, the scammer will judge the financial history of each account and attempt to replicate previous transaction history, such as rent payments or order payments. High usage business accounts will raise no warning flags if they transfer $10,000.00 to another account, while a personal account that has never transferred more than a $1,000.00 would look highly suspicious. This phishing attack is often tied into the previous scam; unknowing mules filter money originating from these hijacked or compromised bank accounts. They offer an effective laundering service for the money and its history.

Bank e-mail scams focus on impersonating the bank down to the last logo, as recipients have to feel safe and confident that the Web site they are being directed to is not only legitimate but safe. Although security Web sites and TV shows often stress the danger of giving out such sensitive information online, many people still think nothing of a bank needing to verify their account, happily handing over any information to anyone who asks.

Banks will never e-mail you for your personal information. If your bank does send you such an e-mail, call them and verify that the e-mail is valid, and look for any suspicious content in the e-mail that suggests it has been used to evade a spam filter or casual reader.

It has been estimated that bank and credit card fraud costs taxpayers over $400 billion dollars annually, and each year the amount of scams continues to grow. Although I don’t mind product-based spam, I condemn money-swindling scams, especially those that try to blatantly deceive and steal from you. These are much more harmful than annoying someone with an offer for Viagra. Recipients have to deal with the stress and paperwork from having their funds stolen. Banks are becoming increasingly skeptical when a distressed client claims their account has been broken into. Someone has to pay for this fraud and banks are becoming more reluctant to fill the bill.

Charity and Fraudulent Donations

In the wake of the tragedy of September 11, 2001, America’s hearts and pockets opened up to those who had lost loved ones, in the hope of helping the needy and grieving. Phishers took advantage of these good intentions by posing as fake relief organizations and collecting millions of donations for the cause. This money was then reinvested into American business by way of purchasing large screen TV’s, game consoles, and DVD players from American retail outlets.

During what is considered the darkest day in recent American history, scammers exploited millions of people, sending millions of guilt-ridden spam e-mails with a simple plea for money, often posed as “official” collectors for the Red Cross or Salvation Army. Americans opened their wallets up for such a worthy cause and scammers falsely obtained an estimated $500,000 worth of donations and relief funds.

Guilt and pity can act as very powerful emotions and charity scams are a great example of just how psychological scams can be. Some scams do not even ask for any money directly, as seen in the following example, which simply asks you to forward the scam to as many people as possible:

My name is Timmy and I am 11 years old. My mommy worked on the 20th floor in the World Trade Tower. On Sept. 11 2001 my daddy drove my mom to work. She was running late so she left her purse in the car. My daddy seen it so he parked the car and went to give her the purse. That day after school my daddy didnt come to pick me up. Instead a police man came and took me to foster care. Finally I found out why my daddy never came.. I really loved him.... They never found his body.. My mom is in the the Hospital since then.. She is losing lots of blood.. She needs to go through surgery.. But since my daddy is gone and no one is working.. We have no money .. And her surgery cost lots of money.. So the Red Cross said that.. for every time this e-mail is fwd we Will get 10 cent for my mom's surgery. So please have a heart and fwd this to everyone you know I really miss my daddy and now I dont want to lose my mommy too..

Guilt-based scams are nothing new to the Internet; you can find traces of their presence on the Internet as far back as 1998. It often comes down to common sense and being aware that legitimate requests for help or financial aide should always be investigated before being trusted.

Advance Fee Payment Scams

Advance free payment scams are some of the most common phishing e-mails on the Internet and they come in two main varieties. First, there is the “You’ve won the jackpot” scam or “You may have won sixty million dollars, as your e-mail address has been randomly selected.” If the e-mail recipient trusts the message, they will become overjoyed; however, they quickly find out that there is a slight catch. In order for the winning check to be written, the recipient must pay a $1,000.00 bank fee to cover the bank transaction fee and the pen-signing fee. Sound suspicious? Perhaps. A little too good to be true? You guessed it. The second you send your bank-processing fee you will never hear back from the mystery sweepstake company. What’s more, you will never receive your winning check, and the only person who will win any money will be the scammer.

The second type of scam is known as a 419 scam. 419 scams are possibly the most notorious of all phishing spams. The term 419 ironically comes from the Nigerian penal code 419 (Fraud), because the majority of these scams originate from Nigeria. The scam focuses on selling a tragic story about money tied up in a poverty stricken country, often involving a dead beneficiary or strict laws that inhibit financial withdrawals out of the country. The amounts of money can vary from $30.00 to $300,000,000.00, but the scam is always the same. First, you are asked if you can help release the money by signing some documents saying that you are related to the deceased. During the e-mail conversations the scammer begins to build a personal relationship with you, pulling you further into the scam.

At this stage, the scammer may ask if you want to meet in person by flying to either their hometown or some other destination in Europe or the UK. Recent cases of abduction have occurred from this; often the victim is held hostage for ransom and, in some cases, is killed. One such case in early 2001 involved Joseph Raca, a 68-year-old man from Britain, who was kidnapped when he arrived in South Africa while attempting to meet his scammer. A ransom of 20,000 was issued to Joseph’s wife for her husband’s return, although he was later released when his captives became nervous of the media attention.

Scammers build strong relationships with their victims. The thought of large financial gain can lure people into a false sense of trust and this trust soon becomes the basis for exploitation. 419 scams have turned psychological exploits into a fine art. A scammer will become your friend and have very positive and reassuring facts to tell you in their e-mails; they will never offend or curse at you. After awhile you begin to sympathize for their situation and want to help. It’s human nature to be friendly towards those who are friendly to us. It is a core part of social development and scammers know just how to use it.

This trust is eventually exploited. The scammer will suddenly tell you that they require a deposit of money to cover a business or financial expense involved in moving or releasing the money to your bank account. Expenses keep occurring and although you think the large payment is just around the corner, it never transpires. You are always reassured, though, when the scammer appeals to you: “What is $6,000.00 when I will give you millions?” That is, until they run out of money and then come back with another fictitious demand for payment.

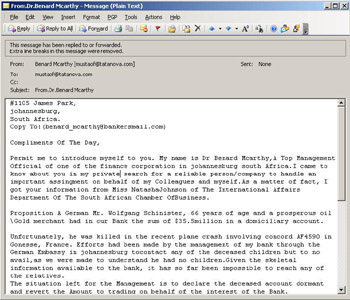

419 scams may be the most psychologically focused and physically dangerous of all online scams, but the methods the scammers use to send the 419 spams are very poor. Figure 9.2 illustrates the body of a typical 419 scam message.

Figure 9.2: Help Me and My Poor Money

The message is plaintext, with no evasion techniques used. The body is quickly identifiable by any spam filter with the mention of key names and amounts. Once identified, hash-based filters would have little problem detecting re-occurrences of this message. Even though this message is boring, predictable, and highly uncreative, when you send hundreds of millions of these scams a day you can afford to have a 99 percent filter rate. A clear lack of general spamming skills is also present in the headers. You can see in the following just how uncreative these scammers are:

Return-Path: <mustaof@tatanova.com> Received: (qmail 29696 invoked by uid 534); 10 Sep 2004 03:26:16 -0000 Received: from mustaof@tatanova.com by SpamBox by uid 89 with qmail- scanner-1.22st Processed in 1.710065 secs); 10 Sep 2004 03:26:16 -0000 Received: from unknown (HELO mummail.tatanova.com) (203.124.xxx.xx) by 0 with SMTP; 10 Sep 2004 03:26:14 -0000 Received: (qmail 21591 invoked from network); 10 Sep 2004 03:11:26 -0000 Received: from unknown (HELO localhost) ([203.124.xxx.xx]) (envelope- sender <mustaof@tatanova.com>) by mail.tatanova.com (qmail-ldap-1.03) with SMTP for <mustaof@tatanova.com>; 10 Sep 2004 03:11:26 -0000 X-Mailer: Perl Mail::Sender Version 0.6.7 Jan Krynicky <Jenda@Krynicky.cz> Czech Republic

These headers are very predictable. They show that the mail came from 203.124.xxx.xx after being relayed through mail.tatanova.com. The X-Mailer header suggests that it originated from a Web-based mailing script, since tatanova.com is an Indian Internet Service Provider (ISP) that may offer a bulk mailing service, or the scammer has a customer account with the ISP and they turn a blind eye to his activities. A Google search for “tatanova.com spam” shows that the host is well known for 419 scams, all featuring the same X-Mailer header. This means the scammer is not new to the business and has been sending scams for many months.

This scammer is also not using any host-based evasion techniques to hide his true origins; there isn’t any need to. There was even a phone number listed in the scam e-mail that belonged to a Nigerian-based cell phone. This means the scammer is probably Nigerian. To my knowledge, Nigeria is not up-to-date on e-crime laws or law enforcement in general. This scammer has nothing to lose; no one in his home country will hunt him down.

This highly unintelligent, brute-force methodology is how Nigerian scams have become so large. An estimated 65 percent of all scam-based spam is 419 scam. Hundreds of millions of spams are sent daily from scammers, all trying to lure money from unsuspecting recipients. The moral of this story is the age-old quote: “If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is.” I am shocked that so many people have fallen victim to this obvious plot and still continue to do so. The largest ever-recorded 419 scam was 181 million U.S. dollars, stolen from a Brazilian businessman by a Logos-based 419 gang. 419 scams are estimated to cost innocent citizens at least half a billion U.S. dollars annually.

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 79