Entry Deterrence

Competition benefits everyone but the competitors. More competition means lower prices and reduced profits. Businessmen would like to come to agreements not to compete, but alas, antitrust laws make such agreements illegal.

Imagine that you run Beta Brothers, which has a highly profitable local monopoly on “bbogs.” In fact, you are probably making a little too much money for your own long-term good. A potential competitor is eyeing your business and figures your huge monopoly profits should be shared. You desperately want to keep the competitor out, but your antitrust lawyer won’t let you bribe it to stay away and you lack the criminal contacts necessary to make physical threats. How can you protect your bbog monopoly?

Would cutting prices to suicide levels deter your rival from challenging you? You could set prices below costs so that neither you nor anyone who tried to enter the market could make money. When your potential competitor abandons its plans to enter your market, you can raise prices to their previous level. By setting suicide prices you make an implied threat that if your rival enters you will keep your low prices and your rival will lose money. Unfortunately, credibility problems make suicide prices an ineffective way of deterring entry.

Your potential competition doesn’t care per se about what price you charge before it enters. If it believed you would maintain suicide prices after its entry, then it would stay away. Unfortunately, your implied threat to maintain suicide prices is devoid of credibility. If the competition enters your market, it would be fairly stupid for you to bankrupt your own business just to spite it. Once the competition starts selling bbogs, it would be in your interest to set a price that maximized your profit given that you have competition. This price is unlikely to be one where everyone in the industry (including you!) suffers permanent losses. Consequently, charging extremely low prices today does not credibly signal to the competition that you will continue to set low prices if they enter your market.

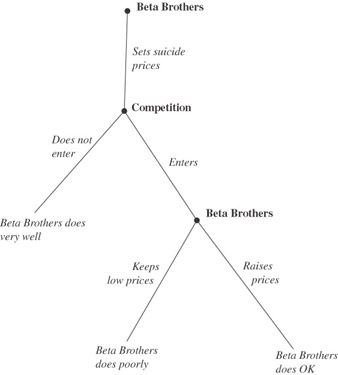

Consider the game in Figure 10. The game starts by assuming that you have set suicide prices. The competition then decides whether to enter the market. If it enters, you decide whether to keep low prices or raise them. If you keep low prices, you lose money (as does the competition). If you raise prices, then you make a small profit. If the potential competition thought that you would keep low prices, then it would not enter. Unfortunately, once it enters, you should raise prices since you are now stuck with the competition. Your rival should predict your actions and enter your bbog market. As a result, setting suicide prices before entry does not keep away the competition.

Figure 10

So, threatening to charge suicide prices isn’t credible. But, what about threatening to set a price that’s low, but not so low that it would cause you to lose money? For example, imagine that it costs you $10 to make each bbog, but bbog production costs your rival $12 per unit.

$10 /unit = your costs

$12 /unit = the potential competition’s costs

We have shown that charging $9 per unit wouldn’t keep out the competition because it would not believe you would keep losing money if it entered. What about charging $11 per unit, however? At $11 per unit you could still make money, but the competition couldn’t, so is $11 your optimal price? To consider this, let’s assume that if the other firm enters, $15 would be the price that earns you the highest profit. If, before the other firm enters, you set a price lower than $15, then the competition should believe that if it enters, you would raise the price to $15. Once you have competition, if there is nothing you can do about it, then you might as well set the price that maximizes your profit. There is no point in setting a very low price to deter the potential competition from entering because the potential competition should believe that it will always be in your interest to raise this price once you know you are stuck with it. Remember, your potential competition probably doesn’t have a time machine, so punishing it after it has entered can’t stop it from initially entering.

Changing prices is easy. In judging what price you would set in the future, the potential competition should not look at what price you are currently setting, but rather at what price it would be in your interest to set if it entered your market.

EAN: N/A

Pages: 260

- ERP Systems Impact on Organizations

- ERP System Acquisition: A Process Model and Results From an Austrian Survey

- Enterprise Application Integration: New Solutions for a Solved Problem or a Challenging Research Field?

- Distributed Data Warehouse for Geo-spatial Services

- Intrinsic and Contextual Data Quality: The Effect of Media and Personal Involvement