Navigating Your Way Through the Day

Hopefully, from weekly organizing, time zones, T-planning, and time tracking, to personal leadership systems,personal effectiveness technology, and “next steps,” this chapter has given you some high leverage help in managing your time and leading your life.

But what it all boils down to is to make good decisions in moments of choice. As Richard L. Evans observed:

Life offers you two precious gifts: one is time, the other, freedom of choice, the freedom to buy with your time what you will.[3]

The quality of what we “buy” with our time is a reflection of our ability to remember and act on what’s most important in the decision moments of our lives.

So how do you effectively navigate through a day? How do you balance the need to focus and the need to be aware? How do you keep the “urgent” from overpowering the important? How do you discern in decision moments what truly matters most?

As you face the day, keep in mind that if you implement the optimizers we’ve suggested, you already have in place a powerful perspective of importance. When you organized your week, you connected with your mission. When you set your goals, you consulted your navigational intelligence and you thoughtfully, consciously, determined the most aligned, high leverage things you could think of to do. When you planned the day, you prioritized your to do’s—both the ones that were time sensitive and the ones you wanted to fit in. So in terms of what matters most, you’re starting the day with your best possible planning.

Keep in mind, though, that what you’ve created is a “flexible framework.” It gives you a standard against which you can measure the importance of unanticipated opportunity, while also allowing you the freedom to recognize genuinely higher priorities and to adjust to them. At the end of the day, the question is not, “How many things did I check off my list?” but, “Did I do what was truly most important?”

So as you move into your day, you can feel free to go into a default “focus” mode. Focus on what you’ve already decided is most important. But be sure to keep your navigational intelligence on constant background scanning. When it sends a signal, tune in immediately and quickly assess. Decide; then focus again—either on your predetermined priority or on the new opportunity or challenge you have now determined is even more important.

As you go through this process repeatedly, day after day, with awareness, you develop the capacity to quickly make better decisions and to shift gears smoothly, swiftly, automatically. Almost in a breath, you can step outside your focus, consult your navigational intelligence, decide on importance, and refocus with confidence. And the process is recursive; the more you do it, the more keenly you calibrate your navigational intelligence and increase your capacity to do it in the future.

Let’s look now at three of the most common kinds of events that might challenge your framework of importance during a day . . .

-

Other people’s urgencies and emergencies

-

Opportunities

-

“Flaky” inclinations

. . . and see how you can use this process and the optimizers we’ve shared in this chapter to deal with them effectively.

Other People’s Urgencies and Emergencies

As part of a recent FranklinCovey survey of more than 11,000 employees in key industries nationwide, participants were shown a list of nine factors and asked: “Which of the following is the most significant distraction that prevents you from completing your most important work tasks?” The top two—by quite a bit—were “interruptions” and “other people’s urgencies and emergencies.”[4] There’s a high probability this is also a problem for you.

So what do you do—at work or at home—when you’re focused on a priority task and someone comes in with an “urgent” request? Here’s where the shift/evaluate/refocus process we just mentioned comes in handy.

-

Shift focus immediately to the person. This accomplishes two important things: It affirms the importance of the person and your relationship, and it also allows you to quickly get the information you need to make a decision.

-

Evalute whether or not this is a true Quadrant I. Engage your navigational intelligence. If the relationship is one of shared vision and high trust, you can work together to determine:

-

Is this a high priority in our shared value system?

-

Is it a higher priority to us than what I was working on?

-

Is the timing critical—or negotiable? (If the relationship doesn’t allow quality partnership interaction, you’ll need to make those decisions on your own.)

-

-

Re-focus. If it is a true Quadrant I—and it’s you’re A-1 Quadrant I—then do what’s necessary to focus your attention on it. If it’s not, you have two choices:

-

Postpone shifting focus. You might say something like, “I can tell this is really important to you. I want to be able to give it the time and attention it deserves. I’m tied up right now, but I could focus on this in a couple of hours. Would that work for you?” This affirms the value of the person, the relation- ship, and the issue. And often, a later time works out even better. It gives the person a chance to move beyond the emotion of the moment and to think and prepare. If the person says “No,” you can use your navigational intelligence to determine whether responding to that person’s perceived needs or staying focused on your current task is the greater priority and act accordingly.

-

Say “No.” If it’s not the genuine priority, have the courage to say “No” and stay focused on what is. Say it kindly, but firm- ly. Give some explanation if it’s helpful and appropriate. But stay focused on what matters most.

-

The advantage of this kind of approach is that it enables you to competently and quickly engage your best decision-making capacity and focus on what’s most important. It also diminishes the tendency to be reactive to or irritated by interruptions. In addition, it builds people and relationships. Keep in mind: you don’t have to be a “people pleaser” to preserve relationships. In fact, quality high trust relationships can only be built as people learn to interact authentically and competently in interdependent situations.

As you deal with urgencies and emergencies, it’s important to remember that sometimes people are energized by their emotions but they don’t really expect you to drop what you’re doing, and are actually surprised when you do. You don’t need to automatically assume that anything that has high energy behind it is an emergency or that the expectation is that you act immediately. And even if it feels like an “emergency” to someone and there is an expectation for you to respond, it may not be appropriate or best for you to do so. As the saying goes, “Lack of planning on your part does not constitute an emergency on my part.” At home, for example, if parents are continually pulling a child out of scrapes created by his lack of planning, that child may never learn to plan.

Also, some “emergencies” are created when people set artificial deadlines—deadlines that often can be changed. For example, suppose a coworker says, “I hate to bother you, but this is an emergency. I’ve promised a client this report by 5:00 and I really need your help!” You can find out if the promise was your coworker’s idea or your client’s. Your coworker may have suggested the time, and the report would simply sit on your client’s desk until 9:00 the next morning. By arranging to come in an hour early, the two of you might be able to get your important tasks completed today, do a good job on the report in the morning, and still meet the client’s needs. Often, people rush unnecessarily to get things done in a crisis mode, only to have them sit on a desk until someone can get to them.

The point is that sometimes things that seem like emergencies are not. So consult your navigational intelligence and quickly determine whether something is really in Quadrant I before you respond.

Also, don’t overlook the fact that there is significant Quadrant II work you can do to minimize interruptions and protect your focus time. At the office, for example, you can set up systems to insulate and isolate yourself for high leverage tasks. You can set up and make people aware of time zones. If you have a secretary or an assistant, you can train him or her to screen visitors and calls. You can build high trust networks and create an environment that facilitates respect for focus time and clear communication in times of real need.

At home, you can also create time zones. You can set up times when the family knows you’re there and that they can count on you. If you have to spend time on a work project, you can communicate its importance and set up a system to remind family members when you’re on task. Here, too, you can work to build relationships of trust so that family members understand and respect an individual’s needs for focus time. However, as we’ve said before, it’s important to remember that some jobs, such as parenting, are basically jobs of responding to interruptions. As much as possible, “interruptions” should be viewed as “opportunities” when you’re at home.

Keep in mind that the more you invest in Quadrant II—in things like building relationships, long-term planning, and preventive main- tenance—the fewer real Quadrant I emergencies you’re likely to have, and also that Quadrant II investments in health and true recreation can also increase your reserves to handle emergencies well.

Opportunities

Sometimes opportunities come up during the day that are genuinely more important than what you had on the plan. On the other hand, some “opportunities” are diversions in disguise. So how do you tell the difference? How do you seize the opportunities and avoid the diversions?

First and foremost, this is an issue of importance. If it’s “above the line” in Quadrant I or II, it’s important. If it’s “below the line” in III or IV, it’s not. So screen it first through the filter of importance. If it can help you nurture a relationship, build your reserves, increase your capacity, contribute in a meaningful, or resolve a crisis, it’s definitely worth considering.

Then, it becomes an issue of relative importance. You’re working on important things; is the opportunity more important? Does it better enable you to do what matters most than what was on your plan? This is something your navigational intelligence can help you determine. If your intelligence has been calibrated through personal mission statement contemplation, weekly planning, and thoughtfully evaluated decision moments of the past—and if it’s open to inspiration—there’s a good chance a quiet moment of connecting will give you the answer.

Keep in mind that some of the best opportunities that come up often give you only a split second to decide to respond. This is particularly true of relationship-building opportunities, such as teaching moments with young children, conversations with teenagers, or helping a coworker or neighbor with an immediate need.

That’s why it’s so important to calibrate your navigational intelligence, keep it constantly on “scan,” and develop the habit to use that split second to listen to it. If you’re so focused on what you’re doing that you miss that split second window, it’s gone.

This is another reason to invest in Quadrant II. The more renewed you are—physically, mentally, and spiritually—the more open and responsive you’re going to be to opportunity moments. Quadrant II is not passive; it’s the key to a dynamic, energetic, responsive approach to life.

“Flaky” Inclinations

Sometimes, what challenges “importance” the most is simply a sub- conscious desire to avoid a particular project or task, or a lack of character strength to follow through.

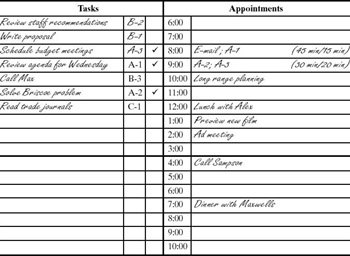

Suppose, for example, that you’re a manager, and your day looks like this: You come into the office at 8:00 and, despite interruptions, you get the first three to do’s checked off your list. At 9:55 you get up and walk around your desk. In five minutes you have a two-hour appointment scheduled with yourself to do some long-range planning, which you have identified as your most important task of the day.

At the moment, though, you find you’re feeling restless. You’ve already put in two or three hours, and suddenly long-range planning sounds boring. You glance out the hall and see several of your coworkers gathered around the water fountain. Taking a little time to chat with them, responding to your e-mails, or checking off more to do’s on your “anytime” list suddenly seems far more appealing than long-range planning. You’re not consciously thinking, “I won’t do what’s on my plan”; you’re just in danger of letting your priority slip, of getting distracted and losing focus. You don’t have the same sense of perspective you had when you planned that time at the beginning of the week.

This is what we call a “moment of truth.” This is when you ask yourself, “What’s really most important now?”

If you review your week’s plan and consult your navigational intelligence, you will probably realize that it’s the long-range planning, and that to act with integrity in that moment means keeping your commitment to yourself. You might look for ways to help— spending five minutes doing “office aerobics,” envisioning the results of having a quality long-range plan, or having a high protein snack that will sustain your blood sugar level. But, bottom line, if you make the decision to follow through with your planning, you will likely feel much better at the end of the day.

Staying with your priorities, even in the midst of temptation to do otherwise, is a function of habit and character. The more you make good decisions when you’re tempted to be “flaky,” the stronger your character and ability to make similar decisions in the future will be. It’s like exercise—if you want to build a muscle, you have to exercise it. If you want to build your character, you have to exercise it. It may be difficult. You may “sweat” a little and experience temporary discomfort.

But the fact remains that you can do it. And the rewards are definitely worth the effort. At the end of the day, you can go to bed knowing that you did what was most important—that your long- range planning (which will affect the quality of every future day) is done . . . and that you have become stronger in the process.

Keep in mind that life is a process of becoming. Navigating well is not something you can expect to do perfectly every day. But it is something you can expect to improve in. Day by day, as you engage your navigational intelligence—as you identify what’s important, act on what’s important, evaluate your experience, and course-correct—you’re going to get better at doing what matters most.

[3]Evans, Richard L., taken from our personal notes after seeing an inspirational film, Man’s Search for Happiness, in the 1960s.

[4]FranklinCovey/Harris Interactive “xQ™” (Execution Quotient) Survey. Survey results are accessible at www.franklincovey.com.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 82