Optimizers

Understanding the “importance” of the importance paradigm, let’s take a moment now to look at six aligned, high leverage optimizers that help us focus on importance. A few that we’ve shared in previous works continue to prove extremely valuable. We will share those here in an abbreviated way that specifically deals with work/home balance issues, and we’ll provide additional references for those who want to go deeper. Others deal with the more recently developing challenges and opportunities, such as those created by technology. We will address these in greater detail.

While we recognize that there are other important optimizers that impact on our time—such as maintaining good health—the ones we’re focusing on here are more process specific. They will help you integrate important goals, such as improving your health, into your life.

Optimizer 1: Plan Weekly

Weekly planning is a process that grows out of the Quadrant II paradigm. It enables you to create a framework of importance to keep in front of you as you execute and make decisions each day.

Basically, it involves choosing a quiet time at the beginning of the week when you can have a few minutes alone, during which you:

-

Connect with what’s most important. Review your personal mission statement if you have one. If you don’t, just take a few minutes to focus in on the core governing values in your life.

-

Write down your roles. These would be your roles as an individual, spouse, parent, manager, PTA president, etc.

-

Set goals. Engage your navigational intelligence. As you look at each role, ask yourself, “What are the one or two important things I could do in this role this week?” (You’ll probably discover that many will be Quadrant II goals.)

-

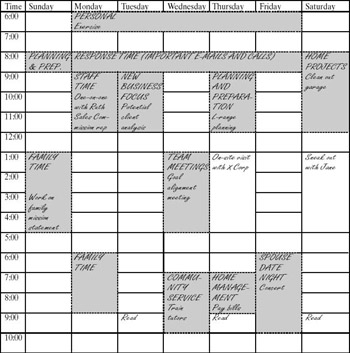

Calendar your goals. Transfer your navigational insights into your calendar first—either as an appointment or as a particular day’s to do. Then fill in other activities as you can.

This organizing process goes a long way toward helping you create life balance. It reminds you of what’s important overall. It reminds you of your various roles in life. It increases options for synergy and balance by helping you consider the entire week before you focus on a single day. It engages your navigational intelligence in determining goals that are most aligned and leveraged, and it helps you put those things into your week first.

It also keeps you focused on importance. By calendaring key activities first—your Job One priorities, professional development time, a weekly family night, a daily dinnertime, a date with your spouse, or a special one-on-one—you create a framework of importance against which you can measure the value of any unexpected opportunity or challenge that may come up.

Finally, it provides an ongoing process for effectively incorporating all other optimizers and Quadrant II activities. Each week, you can use your navigational intelligence to determine which goals provide the highest leverage for you. Over time, this will enable you to implement many of the things we’ve talked about in this book as well as other high leverage ideas you may come across.

Optimizer 2: Use Time Zones

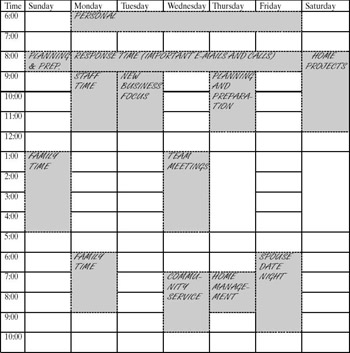

One way to further enhance the effectiveness of your weekly organizing is to use “time zones”—large, interchangeable blocks of time designated for specific kinds of important activities.

During work time, for example, you might create time zones for handling mission-critical e-mail, prospecting for new clients or developing professional skills. At home you might schedule time zones for having a weekly family time, going on a date with your spouse, or doing home projects.

The objective in creating time zones is not to fill the week, but to create a few blocks of time specifically reserved for certain types of high leverage activities and goals. This enables you to channel activities for maximum effectiveness. It’s like building corrals into which horses of different breeds are then placed. When you set up a repeating time zone—like blocking out one specific night a week for family time—the activities within that time zone may vary from week to week, but the nature of the activities would not. In other words, no horse—unless it’s a “family” horse—gets through the gate.

Many effective time managers use time zones, whether they call them by that name or something else. Time zones are valuable optimizers for at least four reasons:

First, they enable you to schedule meaningful chunks of time for those aligned, high leverage (often Quadrant II) activities and goals.

Second, they allow you to group similar activities and goals, facilitating greater organization and focus, so you don’t get diverted by switching from one thing to another all the time.

Third, they facilitate more effective interdependence. When someone calls for an appointment or wants to consult on a particular project, for example, you can generally channel it into the time zone you’ve set aside for those things. When work teams agree on time zones, it becomes easier to schedule meetings and protect independent focus time. Family time zones make it easier for family members to plan quality time together without running into scheduling problems, and to say no to other, less important things.

Fourth, time zones are flexible. If something genuinely more important comes up, you can shift a time zone to another time. Be careful, though, when you need to shift time zones that involve others. When family members are counting on a family priority time, for example, it can be a real downer if you don’t create awareness of and agreement on the priority need for the change.

Optimizer 3: T-Plan Daily

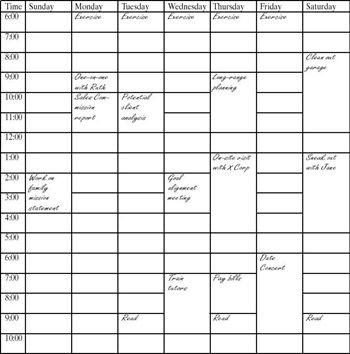

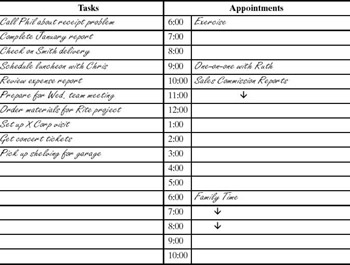

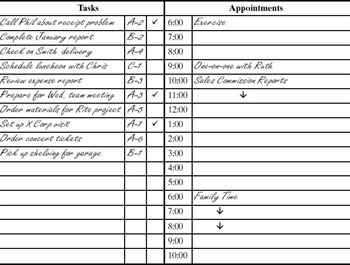

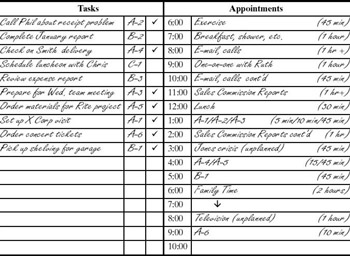

As you begin each day (or on the night before), take a few minutes to plan your day. The most effective way we’ve found to do this is to use a “T-Planning” structure that allows you to put time sensitive activities and commitments on one side and those that can be done at any time during the day on the other. Many of the current electronic and paper planning systems are set up this way.

After you review or list your to do’s, prioritize them in terms of importance. One effective way to do this is to first group your to do’s in terms of general importance—A being high, B medium, and C low, for instance. Then number the items in each group in the order in which you plan to do them.

But watch out! Even with Quadrant II organizing, many people still tend to prioritize to do’s in terms of what’s urgent out of habit.

Take a minute and think about the last time you prioritized a list. Did you put the things that really mattered most at the top, or the things that were most proximate and pressing? Is the way you prioritized your list a pattern in your life? What’s happening as a result?

Also, when you prioritize, be sure to consider items on both sides of the “T.” Just because something is scheduled at a specific time doesn’t necessarily mean it will have priority when that time arrives. You may be involved in something that is genuinely of a higher priority and need to adjust.

As you navigate through the day, this T structure allows you to meet the top priorities on your schedule and to integrate “anytime” priorities most appropriately into the flow of the day.

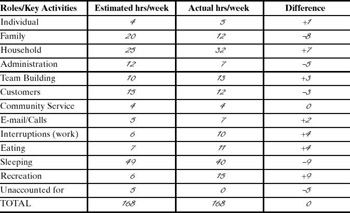

OPTIMIZER 4: TRACK YOUR TIME

ROGER

When I first began working in the field of time management, I found that one of the best ways to help people manage their time better was to help them see where they were actually spending it. Like others in my field, I recommended that people keep a “time log” and track their time to get a realistic picture.

The results never failed to surprise the time trackers. People were consistently shocked to discover that what was actually happening in their lives often bore little resemblance to what was on their schedules or in their minds. But after they got over the initial surprise, they were amazed at the insights the log provided for improved efficiency and effectiveness.

In more recent years doing a time log has fallen out of vogue— probably because it takes additional time and follow-through. But the reality is that people who are truly good with their time know where their time goes—just like people who are good with their money know where their money goes. And the most effective way to find out where your time goes is to track it.

Time tracking is a high leverage Quadrant II activity. It empowers you to better align and leverage your time and to tighten up and eliminate inefficiency and waste. It alerts you to potential Quadrants III and IV “black holes,” including:

-

E-mail

-

Meetings

-

Shopping

-

Web surfing

-

Addictive and nonrejuvenating diversions

-

Inefficient technology

-

Technology shopping

-

Computer games

-

Snacking

-

Television

Like keeping track of what you eat when you’re trying to lose weight, time tracking shatters whatever illusions you may be living with that muddy the lines between intent, perception, and performance.

One way to discover for yourself the value of time tracking is to keep a time log for two different weeks. Before you start, answer the following questions:

-

What are the most important things I should be spending time on (specific relationships, projects, tasks, etc.)?

-

What percentage of my time do I think I’m spending on each of these priorities?

Then track your time. As you review the record, ask yourself:

-

How much time am I actually spending on these priorities?

-

Where is my time going instead?

-

How can I create better alignment?

One effective way to track your time is to note the actual time elapsed for each appointment or task on your planning page.

Lawyers, accountants, consultants, and others who bill by the hour become good at time tracking, though many fail to use the information for effective feedback and evaluation. Time tracking can be a powerful feedback tool. There’s no way to get a more realistic view of how you’re actually spending your time.

Optimizer 5: Build Relationships of Trust

REBECCA

After working through the drafts of The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, there was much editing to do as the manuscript went back and forth between Stephen and the publisher. One of my tasks was to work through the editor’s recommendations and then review proposed changes with Stephen.

As I worked with Stephen, I realized that he was careful and attentive to every detail. I could sense that it was extremely important to him to be aware of and approve any change.

At one point I said, “Stephen, I will not change a comma inthis manuscript without your being aware.” Suddenly, he seemed to relax. What was important to him was recognized and attended to. In that moment, it seemed a bridge of trust was created that moved our relationship to a new level.

That was a very precious moment to me. I felt the different level of trust, and it was a good feeling. I am convinced it greatly increased our effectiveness on that project, and opened the way to far greater synergy and productivity on future projects as well.

When we hear the phrase “time management,” most of us think about how we can independently plan and accomplish a project or task. The reality, however, is that life is highly interdependent. Our ability to accomplish what’s most important is very much tied into the quality of our relationships with the key people in our lives.

This is true of the bigger picture—our ability to work on major projects and make important contributions—as well as on the “front lines” of day-by-day living, where conflicting time demands create some of our most painful life balance decision moments.

Suppose, for example, that you have an appointment scheduled with a key client at four o’clock tomorrow afternoon. Your daughter’s soccer team just qualified for the playoffs. The first game? Four o’clock tomorrow afternoon. What do you do?

Let’s say you decide to talk with your client to resolve the problem. And let’s assume that your mode of operation with this client is one of continual “overpromise and underdeliver.” Your credibility is low. What’s going to happen when you say, “I have a problem. Is there any way we could work something out?” Likely, you’ll encounter inflexibility: “Not on your life!” or “Sure, go ahead. I’ve just been waiting to go to another supplier anyway!”

On the other hand, if your mode of operation has been to realistically promise and overdeliver—always exceeding expectations, anticipating needs, solving problems even before they become apparent—the response you get will likely be totally different. Your client knows that you have his interest at heart, and so will probably be willing to try to reschedule, solve the issue over the phone, or come up with a viable third alternative to meet the need.

The same scenario will likely be played out if you try to negotiate with your daughter instead. If you never attend her soccer matches—even those you promise to attend—she rarely sees you, and you’re always on her case about something, when you tell her you can’t come to her game because of your meeting, her response might well be: “Right! Who’d expect you to come anyway?” Any effort you make to explain the situation will only make it worse.

On the other hand, if your daughter knows you’re her biggest fan ...if, even when you can’t attend, you always make it a point to ask, “How was the game?”...if you know what’s going on in her life . . . if you listen to her and spend time with her and she knows that she’s one of the most important people in your life . . . then you’ll likely get a different response: “I understand. You have to work sometimes. It’s okay.”

The point is, to a great extent our ability to resolve conflicting time demands effectively is dependent on the quality of our relationships with the people involved. When the relationship is good, there’s a trust and willingness to work things out. In fact, the very process of working them out can actually build the relationship. But when the relationship isn’t good, conflicts create additional problems. People feel their expectations are in danger of being violated, and even efforts to solve the problem can actually make the situation worse.

So how do we build relationships of trust?

Basically: value the person. Value the relationship. Treat others the way you want to be treated yourself. Keep the promises you make. Do the things we’ve talked about at work and at home that build relationships of trust. Recognize and respect the fact that other people have their own expectations, their own needs, their own problems and schedules. Interact with them in win-win ways that not only solve the immediate problem but build interdependent problem- solving capacity for the future.

There are many books that contain excellent relationship-building ideas. We encourage you to just make sure that what you read and do is based on solid principles of effectiveness and character and not on manipulative, personality-based “tricks” or “techniques” designed to help people essentially use others to get their own way. Unfortunately, many approaches masquerading as “time management” are simply ways to get other people and their needs and issues out of the way so we can do what we want to do. But rich relationships and the ability to interact and work effectively with others are vital parts of life balance, and any practical approach to life balance must recognize and deal with this essential interdependent dimension.

Genuine trust can only be created when your own heart is right—when you’re sincerely trying to build the kind of relationship that will benefit everyone involved, and to facilitate maximum long- term cooperation and contribution. In the end, the greatest benefit may not be in what you get done, but in the relationship you build in the doing.

Optimizer 6: Utilize Technology in Your Personal Leadership Systems

Now we come to what is potentially one of the most facilitating or debilitating time management issues of our day—technology.

From technophobia to technomania, there’s an enormous range in attitudes, awareness, expectations, comfort levels, and competence with all things that beep, click, and manipulate at high speed. But whatever our personal response may be, the reality is that we live in an increasingly technological world. There’s no way we’re going to abandon cell phones for land lines or computers for typewriters. The ability to navigate in the midst of technological change has become essential.

So how do we do it? How do we spend appropriate time investigating, evaluating, and learning how to use new tools without getting sucked into a black hole that consumes our time and money? How do we tell when some new or different technology will increase our effectiveness . . . or when it’s simply a “red herring” that will divert our time and resources and derail our efforts to do what matters most?

It is not our intent in this chapter to evaluate every new personal effectiveness technology on the market today. The options are far too numerous. And your needs are unique to you. Even the specific industry you’re in may well have its own approach. In addition, whatever may be out there now, you can be guaranteed there will be new options tomorrow.

Instead, our objective, is to equip you to:

-

Wisely select the tools and systems that will help you do what’s most important most effectively.

-

Learn to quickly recognize and take advantage of “better” when you see it.

In order to do these things, you’ll need to understand systems, tools and options. Empowered with understanding in these areas, most people find it much easier to navigate with confidence through the world of technological change.

Understanding Systems

A “system” is a group of interdependent elements that form a unified whole and interact synergistically to serve a common purpose. There are all kinds of systems, both natural and manmade: ecological, weather, solar, respiratory, digestive, irrigation, political, and school systems, among others. As we suggested earlier, “balance” itself is a system—a highly integrated dynamic equilibrium.

Recognizing the interrelatedness of elements in systems, people have begun to approach solutions in a way that acknowledges that interdependence. Systems analysis in business, holistic health care, and environmental ecology are a few examples. To ignore this inter- relatedness and focus on only one element in a system is usually ineffective—often even counterproductive.

With all the demands and complexities of time management and personal leadership, it’s time to bring this powerful systems approach to the personal level. We need to explore the systems in our lives that either facilitate or debilitate our efforts to create life balance—our planning system, our information system, our communication system, and our finance system. And we need to look at the larger system—our personal leadership system—of which each of these smaller systems is an integral and interdependent part.

Your Personal Systems

To one degree or another, you already have personal leadership systems in place.

Planning system. Your planning system deals with how you translate your mission and goals into the way you spend your time. You may use a high-tech electronic planner or online group calendar. You may use a paper planner. You may use sticky notes and a Mo’s Mart calendar on the fridge. Or you may simply keep it all in your head. But in some way and to some degree, you plan and schedule your time. With the addition of space for things such as phone numbers, family and client information, expense sheets, and a daily log, your planning system may also be a major component of communication, information, and financial flow.

Information system. Your information system deals with the things you keep track of. You may keep detailed written records, tape recordings, or a secretary’s minutes. You may keep birthdays, anniversaries, phone numbers, and clothing sizes in an organizer or on a computer. You may keep newspaper clippings and information on household services in a file drawer. You may rely on your memory and live with the consequences. But in some way and to some degree, you have some kind of system to keep track of information.

Communication system. Your communication system deals with how you communicate with others and how they communicate with you. It may include written letters and memos. It may include e-mails and faxes. It may include land lines, cell phones, and answering machines. Or it may be tom-tom drums across the valley or yelling out the back door. But you have some system of communicating with other people.

Finance system. Your finance system is part planning system and part information system. It deals with how you keep track of your financial strategy and goals, your actual investment and spending, and alignment between the plan and the actual. You may keep your strategy and goals in your planner, on your computer, or as an electronic bank balance that simply shows if you’re overdrawn or you have money left in the account. You may keep financial records on a PDA (personal digital assistant), in a checkbook, or in a shoe box, or you may have a bookkeeper do it for you.You may compare planned to actual spending through a budget review, the amount of cash you have in your wallet at the end of the month, or an unexpected over- drawn notice from the bank. But to some degree or another, you have a system that keeps you somewhat aware of the money you spend and what you owe.

Personal leadership system. As we’ve observed, your personal leadership system is comprised of the four smaller systems. The degree to which these systems interrelate in helpful ways is the degree to which your personal leadership functions effectively. You may have a cell phone that has a built-in contact file but doesn’t allow you to transfer contacts from the program on your desktop computer. As a result, you have to enter 200 contacts by hand. You may use a laptop computer, but have frustration trying to sync information to your desktops at the office and at home. How the parts of the larger system work together is at least as important—if not more important—than the way the parts themselves work. The more fully you align and integrate your smaller systems, the more effective your personal leadership system will be.

As we’ve said, you already have these systems in place. You may have inherited elements of your systems from the family you grew up in, bosses or work associates, friends who found something that worked for them, response to advertising, or, in some cases, wise, conscious choice. Even abdication itself is a system, with accompanying consequences and effects.

The question is: Are your systems working effectively for you?

No matter how many “bells and whistles” the tools in your systems may have, no matter whomever else they may have worked for, no matter what they’re advertised to do, the fact remains that your tools are part of a system. And if your systems don’t work for you, they’re not effective.

To paraphrase colleague and systems expert Dave Hanna,“Every system is perfectly aligned to achieve the results it creates.”[2] So if you aren’t satisfied with the results, back up and look at the system. Effectively working on the system as well as in or with the system is a high leverage Quadrant II investment of time.

Evaluating Tools

In this day and age it’s easy to get carried away with the glitzy features of some new tool. But to be effective, we have to learn to look at the tool in the context of the specific system it will be part of, and also to see it in the context of the larger, overall personal leadership system. If a particular tool doesn’t do what we need it to do or if it won’t inter- act with other tools in the system, then any way you cut it, it’s not going to be an optimally effective investment of time or money.

To decide if a tool is right for you, we suggest that you consider it in light of four factors:

-

General evaluation criteria

-

Distinguishing characteristics

-

Your specific needs

-

Cost/benefit analysis

General evaluation criteria. When you consider a new tool, you may find it helpful to ask yourself four general evaluation questions:

-

Is it effective? Does it help you do what’s most important?

-

It is efficient? Does it do it in the best possible way?

-

Is it simple? Is it streamlined, easy to work with, free of complicating “bells and whistles”?

-

Is it synchronous? Does it work in cooperation with your other tools and systems?

Answering these questions can help you evaluate the tools you’re currently using as well as ones you may be considering.

Distinguishing characteristics. There are different ways to categorize devices based on this criteria, and some of them overlap. For example, a PC (personal computer) could identify anything from a desktop computer to a handheld PDA (personal digital assistant). But the distinguishing characteristic that may make a difference to you is the fact that it’s handheld or portable. So “handheld” devices may be a category of tools you want to explore. “PC” would also include devices that provide both keyboard and pen entry. But if the characteristic that’s important to you is the fact that you can write on it, you may want to explore “pen entry” products, including things such as paper planners that aren’t even included in “PC.”

Our point is that there are a number of different ways to categorize. Our objective is not to attempt to redefine industry terminology, but to provide a simple way—from a user’s point of view—to look at the unique characteristics of a product that might make a difference in your situation.

For the purposes of this chapter, we’ve identified six categories of tools—paper-based, PC-based, handheld, wireless, Web-based, and pen-based. The distinguishing characteristics of these categories can provide an effective primary filter for decision making. For example, if you’re trying to operate in a system that requires fast electronic communication and turnaround, you can quickly determine that a paper-based tool would not be the best choice. On the other hand, if portability is the primary need, it might be ideal. At least it would make it through the primary filtering process for consideration.

As you consider each group of tools, consider the advantages and disadvantages of each. Think about how the distinguishing characteristic might affect your choice with regard to your current circumstances . . . and also with regard to other circumstances, should your work or home situation change.

Paper-based tools include sticky notes, notepads, notebooks, three-by-five file cards, desk or wall calendars, paper-based organizers, or forms printed off a computer. Paper-based tools are generally easy to use, carry, and file.

PC-based tools include anything from a desktop computer to a laptop computer to the new Tablet PC’s with digital ink capability. They have a huge capacity to process and store. The function they perform—such as calendaring, word processing, organizing, tracking financial goals and expenses—depends on the software program they’re running.

Handheld tools are basically minicomputers. There are various handheld devices; examples include Palm Pilots and Pocket PC’s. These tools are highly portable and will run some programs, but they do not offer the full range and complexity of a regular computer.

Wireless devices can communicate with other devices, people, or the Internet without the use of wires. Cell phones, for example, are inherently wireless. They, too, are highly portable. They make it possible to communicate with other people, and have sufficient computing capacity to achieve Internet access and information retrieval. Other devices, such as laptops, can be turned into wireless devices with the addition of a wireless card.

Web-based tools allow you to perform tasks such as planning and financial management online. Because the information resides on the server of the supplier, you can access it from any device that can be connected to the Web.

Pen-based devices—using a pen or stylus for entry—have been around for some time, but with the exception of handheld devices, they have met with limited success. However, recent advances in technology appear to be making a major shift in the pen-based category. Many believe this will open the world of personal computing to those who have felt limited by keyboards, and will encourage computer use in situations—such as business meetings—that are still alien even to laptop keyboards.

With the rapid rate of technological change, new devices will come and go. One major trend today is “convergence”—merging two or more functions into one appliance. Creating a cell phone that is also a PDA, for example, eliminates the need for one device. Another trend is wearable appliances. Currently in development are PDA watches, cell phone watches, and eyeglass computer screens.

The point is, identifying the distinguishing characteristics of any tool will better enable you to understand whether it will fit into your system and meet your needs. It will automatically eliminate many tools from consideration. It will help you avoid becoming distracted by advertising and focus your attention on the tools that have the greatest potential of working well for you.

Keep in mind that, though your personal leadership system may well include tools from some or all of the six groups, it’s important that the elements work together effectively. Remember, you’re dealing with a system. The parts need to work together to create an effective, efficient, simple, synchronous whole. Don’t be led astray by “bells and whistles” advertising for some new tool that does not even have the right basic distinguishing characteristic to be compatible with your system.

Your specific needs. In considering a tool, you’ll want to careful- ly identify your own specific needs. You may want to ask questions such as the following. You might even want to rate the questions according to importance.

-

How much of the time will you be in your office versus in other people’s offices (a corridor warrior) or traveling (a road warrior)?

-

How much information do you need to have with you?

-

How do the people you work with communicate and process information?

-

What kind of capacity do you need (such as huge amounts of storage capability for large graphic or scientific files)?

-

How often do you connect with the Web, and for what reasons?

-

What systems does your organization offer, and with which ones do you need to interface?

-

How often do you need to look at your daily plan, task list, calendar, e-mail, or other information, and what circumstances are you in when you look at them (in a noisy environment, in an office, a car, etc.)?

-

How comfortable are you with a keyboard?

-

How comfortable are you with learning how to use a new technology tool?

-

Do you do a lot of long distance calling? Do you use a lot of long distance minutes from locations other than your home?

-

How often do you need to access information (and what kinds of information do you need to access) when you would not be near a computer or have one with you?

-

What kinds of information do you want to have at your fingertips? When and where will you be when you use it, and where is that information now?

This list could be expanded to include far more detail, and for some people, a deeper level of analysis could be very important. Certainly it would be if you were buying systems for 500 employees. But for most of us, these questions bring enough key issues to light to help us get a handle on our needs.

Cost/benefit analysis. To invest in new technology almost always costs money—sometimes a lot. But there are other costs as well. There’s the cost of time and effort required to research, acquire, and set it up. There’s also the cost of time and effort to learn how to use it. There’s the maintenance cost—the money and time required to keep it in functioning condition. And finally, there’s the opportunity cost—whatever else you could have done with the money and time you invested in it. So there’s a lot to consider when you “count the cost” of investing in new technology.

On the other hand, to stay with what you have may incur an even greater cost in terms of the increased effectiveness and/or efficiency you might have had.

So how do you know if some new technology or tool is worth the price of change?

First, you can reconsider the fundamental evaluation questions with the new technology in mind:

-

Is it more effective? Will it help you do what’s most important better than your current system?

-

Is it more efficient? Will it help you do what’s most important in a way that is better than your current system?

-

Is it more simple? Is it more streamlined, easier to work with, freer of complicating “bells and whistles”?

-

Is it more synchronous? Does it work better in cooperation with and better help facilitate your other systems?

-

Does it better meet specific needs (such as portability)? Which needs? And how important are those needs?

Second, keep in mind that while many new technologies sport advanced features that promise to do nearly everything but clean the kitchen sink, even suppliers acknowledge that many people do not actually use these tools as they were designed to be used. Consider planning tools, for example. Advanced paper-based planners often wind up being used as nothing more than glorified calendars. Consultants report finding organizers being used as fancy appointment books or left virtually unopened in office desk drawers. Few people use or are even aware of all the features of software programs or equipment such as PDAs.

The reality is that many of us don’t need and simply won’t use many of the “bells and whistles” that constitute “new and improved.” So why pay for them? Why spend the time learning how to use them? If some new technology performs one basic function you need and 29 functions you don’t need, you’ll probably do well to look for a simpler, less expensive alternative.

On the other hand, if the “new and improved” will help you simplify, it usually pays to investigate further. A single new cell phone may genuinely serve you better than your current pager, PDA, and two voice messaging machines. An electronic planning system with a dialable contact file may make it easier to coordinate planning and communication than your current card file or alphabetized list in your planner. A computer-based finance system that helps you align goals and spending, connects your check register to an online bill- paying service, provides online account access, instantly creates charts and graphs to help you track progress and automatically does your checkbook math may save hundreds of hours over time. As a general rule, the more you can combine and simplify, the better off you’ll be.

Third, as you consider new alternatives, keep in mind that your own personal leadership system may well be part of a larger system in which interrelatedness is also an issue. If you work in a situation where information is passed through a specific kind of hardware or software program, keeping abreast of that particular technology may be vital to your effectiveness on the job. In addition, you may want to coordinate your personal systems for greater ease in planning and communication. Remember, too, that a change in your work or home situation may also create the need for a change in your system.

Finally, keep in mind that in most circumstances, you’re generally better off staying a little behind the cutting edge of new technology. For instance, 1.0 version software often has “bugs” that need to be worked out, and later versions are usually less expensive and simpler and have shorter learning curves. Deciding how long to wait to invest in new technology is a function of weighing the benefits against the inconvenience and risk of dealing with the drawbacks.

So be aware—but also beware! If you’re going to catch the wave, generally do it when it’s full and solid enough to support you well.

Our Own Personal Leadership Systems

Over the years, the two of us have used a variety of personal leader- ship tools. Through the following examples, you can see a few specific applications of the principles we’ve talked about.

ROGER

I’ve been working with personal systems for years. I helped design organizers and have trained thousands in their use. I have also been an early adopter of new technologies, from computers to cell phones to electronic tablets.

With this in mind, you can probably understand my enthusiasm for some of the tools that are now available. The major elements to my system include:

a Tablet PC

a cell phone/pocket PC combination

a land line phone

a desktop computer

a wireless home network

an office-based network

The key piece of my system is the Tablet PC. It can run all the programs of a laptop, but in addition you can write on it. In fact, if you can write or draw something on a piece of paper, you can do it on a Tablet. I carry all the key information I need with me on my Tablet PC, including my notes for books and projects. I also have a program that contains the text of over 3000 books and publications that I refer to and search.

For my organizer, I use the Tablet Planner software. I now have what looks like my trusty paper planner on a computer—with all the advantages of both!

One of the things I’m most excited about is my ability to search my notes for a word or phrase and have it pop up. This works whether the note is associated with a task, appointment, contact, or a simple note page. My cell phone/PDA combination is part of a new generation of phones that combines a cell phone and some or all aspects of a handheld computer in one device. The benefits are obvious—I have one less thing to carry, and my wireless, handheld computer can go online with a couple of clicks.

I keep my contacts in my Tablet Planner, which syncs with my pocket PC phone, so I have all my numbers with me when I have the phone. I program my home office phone to my cell phone when I’m away. When I can’t answer, my calls go into my cell phone voice mail. I use instant messaging with close associates and family members.

What’s really been helpful is how these elements all work together. My phone and computers sync. I back up my Tablet PC with my desktop, so the two provide backup for each other. Rebecca and I share files between our home offices and from various parts of the house without ever leaving our seats. The Tablet has wireless built in, and with the addition of a PCMCIA cell phone card, I can also use it over the new and faster connections made available through cell phone providers.

REBECCA

My personal systems are somewhat simpler than Roger’s—I essentially use a desktop computer. I write, do my weekly planning, store contacts and information, manage our finances, plan presentations, and research genealogical records all on my desktop. With our network, Roger and I can shoot files back and forth as we work. During our weekly meeting when we review our shared mission and address issues of planning, calendaring, parenting, writing, and finance, I use my desktop and he brings his Tablet PC.

When most of our children were at home, we planned weekly as a family. We kept two magnetic dry-erase calendars on the fridge—one for the week and one for the month. Each week we would review the events of the past week. Then we’d write down appointments for each family member for the coming week.

In addition to allowing us to coordinate transportation and family events, this gave each of us a chance to know each other’s priorities for the week so that we could give encouragement, help,and support. It was also synergistic in that it provided communication as well as planning and scheduling.

The two of us find ourselves moving more toward computerbased rather than paper-based information storage. We also find ourselves keeping less research in our files. With the Internet, reference CDs, and handheld devices that can carry the contents of a number of key reference books, we find we don’t need to duplicate and keep personal copies of all the information we used to keep. In this sense, technology has helped us to simplify our lives.

These systems work well for us. We know of others who use different tools that work well for them. But whether your system is paper and pencil or ultimate high tech, as long as it’s effective, efficient, simple, and synergistic—and Quadrant II (importance and improvement focused)—you can’t go too far wrong.

Next Steps

In deciding how to best implement the six optimizers we’ve just described, use your navigational intelligence. If one or two seem particularly useful, start there. Or you might find it helpful to evaluate your current situation. Depending on how you see your level of competence in dealing with “time matters,” here are some specific “next step” ideas that may prove helpful.

“I’m out of control!” If you see yourself as basically “out of control,” the best way to begin to move into Quadrant II may be to simply employ the “Five Minute Rule”—spend five minutes today doing something that will make tomorrow better. Maybe you have a customer at work who doesn’t have a problem. Use your five minutes to call her. Build the relationship. Get some specific feedback that will help you with your other customers. Or perhaps there’s someone you didn’t get as a customer. Call him. Find out what you could have done better—what you can do better in the future. If you were to contact one unsatisfied customer a day for five days, you might be able to come up with a consistent thread, with something specific that would make your whole operation more effective. Then you could ask for five minutes at the next team meeting to share what you’ve learned. Improving your team performance by 10 percent— even 5 percent—would give you a huge gain.

Try the “Five Minute Rule” at home. Invest in relationships. Do some of the “happy things” you identified in the previous chapter. Stop on your way home from work and pick up a special treat for the family or a flower or card for your spouse. Read a story to your three year-old or sit down for five minutes and really focus on listening to your teenager or your spouse. Or use your five minutes to plan a special family time, create menus for the week, organize a cupboard, or order garden seeds. Do something that helps organize and beautify your home or builds relationships of service and love.

Once you get a feeling for the power of Quadrant II investments, you’ll want to jump in. The objective is to eventually invest up to 20, 40 or even 60 percent of your time in Quadrant II.

“I’m doing all right, but ...” If you’re a fairly good time manager, but you know you have room for improvement, a good “next step” is to track your time. This will enable you to quickly discover the “black holes” and target specific areas for improvement.Another good area of focus is systems and tools. Streamlining and updating your personal systems can increase your ability to get things done.

“I manage my time well, but I want to get to a new level.” If you consider yourself a competent time manager, but you want to dis- cover new levels of effectiveness, a good place for you to work is in the upper corner of Quadrant II. This is where you anticipate potential opportunities and problems. You deal with emerging needs. It’s engaging your ability to envision and imagine. It’s creating an antic- ipation/prevention focus that enables you to keep things from moving into Quadrant I.

“I’m a great time manager at work, but not at home” (or vice- versa). If you’re competent in one arena of life, but not in another, a good next step is to zero in on the most likely areas of waste. If your problem is at work, analyze the time you’re spending in Quadrant

III. Look for the “urgent, but not important” things that are drawing you away from a highest priority focus. But discern carefully; the feeling of urgency can fool you into thinking you’re in Quadrant I when you’re really in Quadrant III. If the problem is at home, take a closer look at “not urgent, not important” Quadrant IV. If you’re spending hours on the couch in front of the television set, have the courage to push the “off” button and do something that’s truly renewing and relationship-building.

[2]Hanna, David P. Leadership for the Ages, Executive Excellence Publishing, Provo, UT, 2001, pp. 163, 170.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 82