The Keys to Step 3

The Keys to Step #3

Determine Whether the Presenting Issue Is the Real Issue

When an issue has festered for a long time, it's usually a sign that some other issue underlies it. For example, an upscale community had struggled for nearly a decade trying to decide whether to replace its crowded sixty-year-old elementary school. Two divisive school bond issue ballots had failed, and the outlook for any constructive action looked bleak.

On the face of it, the real issue seemed to be the need for a new school. Angry parents of schoolchildren bemoaned, "Our kids are stuffed into old classrooms like sardines. Teachers literally work out of closets. And we can't have a schoolwide event because even the gym isn't large enough. Don't the residents understand this? What's it going to take to resolve this situation?"

"The most important thing in communications is to hear what isn't being said."

—Peter Drucker

When business owners, educators, and residents were asked to talk about their thoughts and feelings regarding the school project, however, a different concern surfaced. As one person stated, "We're worried that the proposed school will stimulate growth that will strain our resources and alter the small-town character of our community." The real issue for many was not a new school but growth.

With the true issue in mind, residents were able to explore options for locating and building a new school that would not result in undesirable growth. They looked for sites closer to the town center and ones along existing transportation routes. The next school bond ballot sailed through with over 70 percent of the vote—an extraordinary landslide.

A similarly conflicted situation arose in a Silicon Valley church. Although it had a well-established congregation, including highly paid executives and successful entrepreneurs, it faced a budget crisis. Dozens of parishioners had come to meetings, and each person had offered a radically different idea about where to cut the budget. The arguments had become personal and intense. As one frustrated congregant said, "I can't believe that we're here in church and tearing away at each other. Can we solve this budget issue before we split apart?" Fear and the divisive dynamics that result from it can trouble any organization.

Certainly, the church had a significant budget problem. But as it turned out, that issue was not the core of the problem. Before sorting through all the proposed solutions, each person was asked to express his or her thoughts and concerns about the church and its budget. No debate was allowed, and no solutions could be championed. Church members could express anything they wanted as long as it was their own thoughts and feelings and not a judgment or an accusation about someone else.

Because forty-five people jammed into the meeting room for what was to be a brief meeting, they used a time-shaving shortcut. Each person wrote his or her thoughts and concerns on letter-size sheets of paper—one thought per sheet. When they finished writing, they posted the sheets on the wall and clustered similar thoughts and concerns together.

This exercise opened the floodgates. In minutes, dozens and dozens of sheets appeared on the wall. The largest cluster surrounded the theme of trust. For example, one person wrote, "There are some topics we need to discuss, but it doesn't feel OK to bring them up." And another said, "People in the congregation don't understand or trust me. They question my motives. I can't share my thoughts easily."

Since it was so clear that trust was actually the big issue, all the participants agreed to turn to that topic and discuss ways to restore trust. Having identified the real issue, they followed Steps #4 through #10 to explore the options and select appropriate courses of action to strengthen their community.

Several months later, the church leader proudly reported the results: "We no longer have a budget deficit. In fact, we have a sizeable surplus!" What had happened? She explained: "When people started trusting one another more, they began to participate in the church more actively. We stopped debating and started working together." As people participated more actively in the church, they opened their pocketbooks and also attracted new members.

These same dynamics can be applied in situations such as developing a new project with potential joint venture partners or raising capital for a business. If you don't know what the stakeholders consider to be the real issues, you can't make progress toward your goal. Reflective listening is a critical way for any organization to pinpoint the issues it needs to address in order to make great decisions that result in effective problem solving.

Listen for Feelings as Well as Content

Reflective listening also helps people solve problems themselves. When people have a chance to say what's on their minds and hear what they've said, they sometimes are able to resolve their own issues.

Remember Mark and Sam? Sam's many calls about the construction project frustrated Mark. When Mark asked Sam to tell him his thoughts, Mark was able to identify and address Sam's real concern. Beneath all the detailed questions about the job was the underlying concern about keeping the budget and schedule in line. Listening produced understanding, which decreased Sam's need to keep calling Mark.

Mirror What People Express

Some people discover what they think through speaking. My experience is that one-fourth or more of people in business and community situations do their thinking aloud, especially on emotionally charged issues. For example, they might say, "I'm really upset about this issue and don't know what to do. Can you listen to me for a few minutes?" Many people need others as a sounding board in order to clarify their own thinking.

When you work with people in this way, some may occasionally respond to your accurate paraphrasing of their thoughts and feelings by commenting, "I didn't say that—or, at least, that's not what I meant." If this happens, don't argue with them. Their thoughts are evolving. Simply offer your reflection of their revised comments and then check again to determine whether you have accurately captured their thoughts and concerns. (See Figure 8.)

Figure 8: Accurately reflect thoughts and feelings.

Mirroring what someone says might seem as if it would take a lot of time. But effective listening is actually a tremendous time-saver. It is a technique for cutting to the chase and uncovering the real issue, and thus frees up time for the group to focus on that.

Reflecting feelings, however, does require tact. Some people may not be open to examining their feelings or having others paraphrase them. In such cases, ask for permission: "May I reflect back what I think I'm hearing?" Remember, you're not trying to dictate to someone what he or she is feeling. You're just trying to reflect the feelings as expressed to you.

Sometimes a person's feelings conflict with what the person thinks. In this case, the person needs an opportunity to resolve the conflict before you can work together effectively. Adopt a lighter tone in such a situation. You don't want to shut the person down by being too heavy-handed in your reflection of what is being said. For example, your approach might be something like this: "I'm not sure, but it sounds like you're saying..."

No matter how wrongheaded or unjustified other people's thoughts and feelings may seem to you, don't edit them. When they hear themselves clearly, they will make the corrections themselves. The open discussion of options, along with their negatives and positives, that occurs in Steps #4 through #10 will also give people many opportunities to revise their thinking without a bruised ego.

Give Physical Form to Thoughts and Concerns

Some people resist expressing their thoughts or feelings. Perhaps they want to jump ahead to solutions, or maybe they aren't aware of any deeper thoughts and feelings than the relatively superficial issue in front of them.

In these cases, invite the relevant parties to depict their views physically. They could draw pictures of how they see the situation, Or they might act out the situation.

For example, an entrepreneur facing a tough organizational issue used a technique called sculpting suggested by Mark Bryan, author of Artist's Way at Work: Riding the Dragon (William Morrow, 1998). The entrepreneur and her team used volunteers to physically represent the feuding departments in the company. They arranged these people—like pieces of sculptor's clay—to depict how the departments interacted. Her business "sculpture" showed the hand-off between design and production and the rub points between sales and finance. After seeing how out of balance the current business sculpture was and hearing from the actors about how it physically felt for them to be in their positions, the team had a fresh perspective on their issues. Through the playful spirit of the business sculpture, they could demonstrate issues that were difficult to express.

Try finding inventive ways to explore the important issues you face.

Target Your Attention Where It Counts

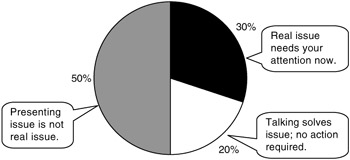

If you take the time needed to listen and learn what the real issue is, you can whittle away the presenting issues and focus on the critical issue that needs immediate attention. Let the involved parties talk out the issues they can solve on their own. What's left will be the real issue that needs attention now in order to achieve the desired result. This targeted issue may constitute only a fraction of all the issues that face you (see Figure 9), but targeting your attention saves time and energy and prepares you for the remainder of the decision process.

Figure 9: Find the real issue.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 112