MAKING SENSE OF A CLIENT S PREDICAMENT

MAKING SENSE OF A CLIENT'S PREDICAMENT

It has sometimes been said that a consultant decides the answer to the client's problem on Day 2 of the project and spends the rest of the project proving that this is indeed the case. If it proves not to be the case, then he or she goes back again and chooses another answer and checks to see whether that is appropriate.

This type of approach may work with simple problems but it is of limited value when dealing with messy problems. It relies on the consultant's preconceptions, and allows little scope for creativity. By contrast, a consultancy problem solving process for addressing messy problems must recognize that preconceptions inevitably exist and engage with them constructively.

Recognizing Preconceptions

It is inevitable that the parties to a consultancy project bring preconceptions that are fashioned by their assumptions. Your judgement about what is relevant in a given situation, for example, will be a function of the skills, knowledge and experience relating to your expertise and its application. Plainly, it is neither possible nor appropriate to try to eliminate expert judgement from consultancy projects. But when entering on any consultancy project - particularly one of any complexity - it is sensible to examine the preconceptions of both consultant and client to see whether they are valid.

For example, a firm of solicitors decided that it wanted to improve the quality of its client service. It therefore engaged consultants to design and run a training course for all staff, which emphasized the importance of good-quality client service and suggested how it might be developed. In the event, the programme failed to improve the quality of client service because of the different preconceptions of the consultants and the solicitors:

-

Each had clear, but different, views of what constituted good client service.

-

The consultancy had previously provided similar training elsewhere, so assumed that this would be an appropriate method with this firm of solicitors.

-

The solicitors took the view that training would be sufficient alone. The consultants failed to challenge this. What was needed in practice, however, was a framework in which people who had received the training could apply it.

Whenever a client and consultant come together, each will have some preconceptions relating to the prospective project. In the example above, consultant and client had similar preconceptions; had these been challenged, a better performance development programme should have resulted.

In other cases, their preconceptions may be different. For example, a consultant may have an idealized view of how a business such as the client's should work and base his or her diagnosis on a comparison of what is going on with that of an ideal. By contrast, the client may see the work required of the consultant entirely in terms of alleviating symptoms.

There are dangers with both perspectives. These can be illustrated by an analogy with a visit to a doctor. Suppose you visit your GP because you have a stomach pain; here, the doctor is in the role of consultant, and you are the client. Taking an idealized view, the doctor might carry out an examination and say, 'I'm afraid you're a little overweight, and you have some skin blemishes. Your eyesight and hearing are not as good as they might be, and you look pretty unfit.'

All this may be true, but none of it is about your stomach pain. A consultant's diagnosis based on a comparison with an ideal will be equally unhelpful to a client.

On the other hand, you would not think much of a doctor who simply gave you tablets to take away the stomach pain, without bothering to examine you at all. The treatment may alleviate the symptoms, but not deal with the underlying problem. For similar reasons, a consultant should not confine his or her intervention to dealing only with the symptoms a client reports. Of course, as with a visit to a doctor, a client will describe the symptoms at the outset, but these should provide simply the starting point for the consultancy assignment.

So, it is inevitable that both client and consultant will have preconceptions about a problem when they start work together. That they are preconceptions does not automatically invalidate them, however. A problem solving process should therefore recognize that preconceptions exist and that they may have value and provide for them to be challenged where necessary.

Developing an Understanding of the Client's Situation

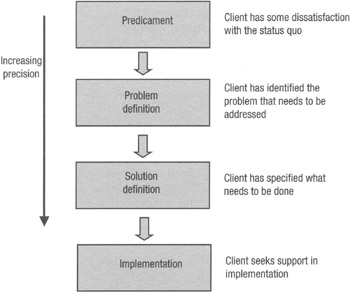

Figure 5.8 in the previous chapter showed the structure by which the thinking of client and consultant could be progressed. This approach is an essential one in developing an understanding of the client's situation; the figure is reproduced above in Figure 6.4 with the addition of a further stage: that of implementation.

Figure 6.4: Progressive precision of specification

There is a structured method to understanding a client's situation, which can be best illustrated by a simple case study: International Cutlery Company (ICC), which is set out below.

John Smith, a consultant, had been invited by the General Manager of the International Cutlery Company to tender for a project for reducing the cost of producing cutlery. 'Our competitors seem to be able to produce it for a lot less than we can - and I want to get our costs down to the same level as theirs', the General Manager explained when Smith met him.

The business was a small subsidiary of Armfather Industries. As he showed Smith round the factory, the General Manager explained what was going on. In one corner, a group of operatives were sitting around laughing and chatting. The General Manager explained, 'They work on the "C" production line; they're having to wait while an engineer fixes the packaging machine.'

Quality control was very interesting; a large number of pieces of cutlery that did not meet specification had been placed in two piles. 'One pile are those which can easily be put right', explained the quality inspector. 'Those others are a dead loss - they could never be fixed.' Smith asked whether the rejects were the result of the week's production so far. 'Goodness, no,' exclaimed the Inspector, 'these are just this morning's.' The General Manager grumbled as they left. 'That means more overtime. Overtime costs are high enough as it is!'

Just as they reached the finishing shop, the General Manager's secretary rushed up to them. 'I'm so glad to have caught you,' she said to him, 'Robinsons are on the line; they want to fix lunch sometime so that they can go over next year's prices with you.'

'I'd better talk to them', said the General Manager. 'Can you excuse me whilst I pop back to my office for five minutes? Robinsons are our major suppliers,' he went on to explain, before he left, 'they produce first class stuff, and their deliveries are always spot on. But, they really charge for it! That meeting is to discuss the price increase they're proposing for next year.'

John Smith went on into the finishing shop with the supervisor who had been hovering in the background since he had walked in with the General Manager. They chatted about the different qualities of finish various customers required. One interesting thing he learned was that most of the specifications had not changed at all over the last five years.

Issue Analysis

The first step when faced with the situation described in the case study is to identify what the issues are. An issue can be prefaced with the phrase, 'I'm worried about... '. At the end of his visit, therefore, John Smith might say, based on his observations:

I'm worried about... :

-

wastage and rework rates;

-

machine downtime;

-

operative waiting time;

-

customer expectations of quality;

-

overtime costs;

-

suppliers' prices.

Based on his previous experience, he might add other issues to this list - for example:

I'm worried about... :

-

the manning levels;

-

work methods used;

-

levels of stocks.

None of these last three points can be inferred directly from those given above; John Smith has added them because of his specialized knowledge.

At this stage, these issues are only conjectural; John Smith does not know whether they are substantive or not. For example, by chance he may have arrived on the only day there has been a machine breakdown in five years, and so machine downtime would not be a major cause of uncompetitive productivity. John Smith might also identify issues that are not related to the General Manager's concern with productivity, for example:

I'm worried about:

-

the General Manager's secretary interrupting us over a supplier's telephone call;

-

the General Manager's response to this interruption;

-

the supervisor's speaking only in the absence of the General Manager.

Having created a long list of worries or issues, it is sensible to try to create some sort of structure among them. They are likely to be related in some ways, so a simple method is to cluster them around similar themes. These diagrams in various forms are called mind maps, spidergrams, or cause and effect diagrams. This layout can often stimulate further thoughts and ideas.

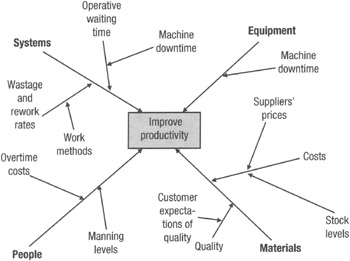

This technique is applied to the case study in Figure 6.5, which shows the issues relating to the purpose of improving productivity at ICC.

Figure 6.5: Issues shown on a cause and effect diagram

It shows the purpose (improve productivity) at the centre of the diagram. Around it are shown the issues that have been cited before, which have been grouped according to theme. Issues can appear in more than one place if that seems appropriate; for example, in the diagram, machine downtime appears twice (on the equipment theme and on the systems theme) as a contributory cause of operative waiting time. In practice, the best way of going about this is first to create an unstructured list of issues by brain-storming and then to map them on to the cause and effect diagram as shown. Writing the ideas on the diagram will help to create more ideas about what others might be appropriate. The figure does not show issues outside the General Manager's presenting concern; these could be the subject of a separate diagram and will be a function of deciding where to start and your freedom to do so (see below). As a practical tip, if a consultant team is involved, then it is useful to do this work as a 'case conference', sharing perceptions, understanding and experience.

Remember that issue analysis is not conclusive; a number of these issues identified will be speculative at best and will need further information before they can be validated (or not). So, issue analysis can be a useful pointer to a requirement for further data.

Levels of Intervention

The issues identified in the ICC case study are of different moment. For example, 'increase the reliability of the packaging machine on the "C" production line' and 'replace the General Manger as he is incompetent'. The latter would require a more profound intervention than the former; indeed, it might not be an option.

The notion of 'levels of intervention' enables you to decide the appropriate starting point for a consultancy project. They can be defined as:

-

Purposes. The aims that the client has in mind when inviting consultancy help.

-

Problems. The problem areas that must be addressed if the purposes are to be achieved.

-

Solutions. What the solutions should be.

-

Implementation. The plans and activities for resolving the problem by means of the chosen solutions.

After the visit the General Manager (GM) of ICC might call up John Smith saying, 'As you can see, our main problem is the "C" production line. We obviously need to refurbish the equipment, and we'd like you to oversee the project.' A level 4 intervention would be for John Smith to implement the GM's plans and support the refurbishment.

At a level 3 intervention, John Smith would accept the GM's diagnosis of the problem, but might question the solution. He might look for other ways of improving productivity on the 'C' production line - for example, by improved methods, materials flow or planning.

If John Smith intervened at level 2, he might identify other problems that could contribute to high production costs, besides those of the 'C' production line. During his visit, he might note:

-

operatives idle while the packaging machine was being fixed;

-

large piles of rejects;

-

high overtime costs;

-

high supplier prices;

-

unchanged specifications.

He would need to check whether these are important contributory factors to high production costs. There may be other problems too, which need consideration.

Finally, if John Smith made a level 1 intervention, he would query the General Manager's initial statement of purpose. Is it true that the production costs of his competitors are less? Does the financial structure of the cutlery business mean that ICC can match its competitors? Would it be worthwhile? These are all questions he might ask at this level.

Although we have defined four levels, they are on a continuum. For example, the more precisely a problem becomes defined and understood, the closer you get to a solution. Each level proceeds on the basis of assumptions about the earlier level; for example, if your level of intervention is about formulating solutions, then this will be predicated on assumptions about the nature of the problems that have to be addressed. Similarly, the definition of problems will follow assumptions about purposes - what is to be achieved in the first place.

Going back to the ICC case study example, having identified the levels of intervention John Smith could make, you can see that the intervention at level 4 cited first is based on assumptions about the preceding levels, namely:

-

ICC's competitors have a cost advantage and ICC must reduce production costs in order to compete (level 1).

-

Improving performance on the 'C' production line will have a worthwhile impact on productivity (level 2).

-

Refurbishing the machinery will improve productivity on the 'C' production line (level 3).

-

So implementing the GM's refurbishment plans will make ICC more competitive (level 4).

There is a clear correlation between this model of levels of intervention and the model of progressive definition shown in Figure 6.4.

Choosing Where to Start

All consultants should be aware of this hierarchy of intervention. Part of your expertise should be to judge at which level of intervention it is necessary to start and to guide your clients accordingly. At the start of any involvement with a client (that is, before a project has been defined) you must therefore ask the question: 'Can I take as read any assumptions about the levels above that at which I am operating, on which my work is predicated? Or is there a piece of work that needs to be done to check these out before I engage in the main piece of work?'

Thinking at a degree of freedom more than that of the client means questioning the assumptions on which a client's construction of any problem is based. For example, a large company decided to make its IT department perform better by insisting that it dealt with all internal 'customers' on a commercial basis. Other departments would then be free to use other sources of IT services if they could be provided more cheaply. The manager of the IT department had considerable misgivings about this. Although there would be short-term cost savings, she believed that in the long term the quality of IT systems and support would fall. She decided to proceed with implementing this proposal, however, and discussed how it might be best accomplished with an outside consultant. The consultant had at this point to choose at what level to intervene. A level 4 intervention would have meant setting up the IT department so that it could function effectively on a commercial basis. With a level 3 intervention (a degree of freedom greater than the client was thinking) the consultant would have looked at other ways in which the IT department could improve its service to other parts of the organization.

In the event, on questioning from the consultant, the manager disclosed her misgivings about this solution. Further probing revealed that the problem was really that internal departments resented the way that IT was costed into their budgets as an overhead, rather than for services received. This meant that alternative solutions - changing the costing system - became more appropriate, and this was the one eventually adopted.

Dealing with clients on these matters has to be handled sensitively to avoid appearing to be extending the scope of an assignment needlessly. On the domestic front, we do not welcome our plumber's help on matters other than plumbing - his advice on our financial affairs, for example, would be intrusive. Similarly, a client may become irritated with a training consultant who tries needlessly to develop a training assignment into matters of corporate strategy. Where a problem is clearly and satisfactorily defined, intervening at level 3, to define solutions, is entirely proper.

Of course, you may well have biases or preferences about where you start on a project. This will be strongly influenced by the type of consultancy in which you specialize. For example:

-

A strategy consultant may always start by questioning the purposes of a client (level 1).

-

A management consultant may focus on identifying problems (level 2) and recommending how they might be resolved (level 3).

-

A technical consultant will help with defining solutions (level 3) and how they might be implemented (level 4).

It is important to recognize these biases because you may be required to work at different levels. For example, an IT consultant may need to clarify problems in order to do the job. Similarly, a strategy consultant may need to follow a project through to detailed implementation. Under these circumstances, the project may be broken into separate phases, each dealing with the question at different levels of intervention.

Phasing

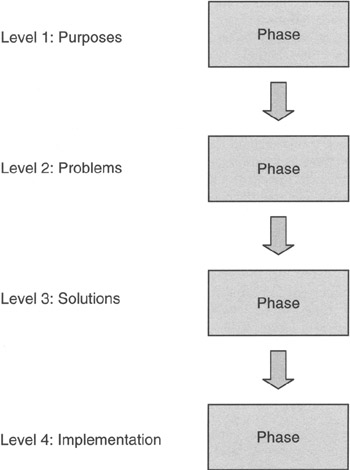

If you start a project with a level 4 intervention, then you can predict with a fair degree of confidence how the project will develop. By contrast, with a level 1 intervention it is more difficult to predict what will happen, as work at subsequent levels will depend on the findings of those preceding. Under these circumstances an iterative approach is appropriate, which breaks the consultancy project down into phases, as shown in Figure 6.6.

Figure 6.6: Successive levels of intervention should be treated as different phases of a project

The work at each level is best dealt with as a separate phase in a project. This implies that in carrying a project through from clarifying purposes to implementing solutions, there should be at least four phases. If you start at level 3, however, you could manage with just two phases. Each phase, of course, could itself be a project with several stages involved.

The example of ICC can be used to illustrate phasing, as follows. The GM telephones John Smith to say that he's concerned about the competitiveness of ICC, and he believes that production costs need to be reduced. John Smith visits the factory; his visit is reported in the account given earlier in this chapter. Based on his appraisal, John Smith accepts the GM's view of the purposes, and decides to start with a level 2 intervention, identifying the problems that lead to high production costs.

At the end of this phase, John Smith might report to the GM with his appraisal of the issues that must be addressed if ICC's production costs are to be reduced. The GM might then ask, 'What should we do to resolve these issues?' This is a level 3 intervention, which therefore forms the next phase of the project. When this is complete, John Smith would report to the GM with recommendations on how the issues should be addressed. Finally, the GM might ask John Smith to implement his recommendations (a level 4 intervention).

Of course, you may not be able to start at the level you ideally would like, perhaps because of your level of entry into the client organization, or because of your client's expectations of you. In such a case it may be best to start at a lower level of intervention and seek to understand the situation better as well as providing help to the client. With a better understanding - and a closer relationship with the client - it may then be possible to present your views in a way that the client accepts.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 89

- Challenging the Unpredictable: Changeable Order Management Systems

- The Second Wave ERP Market: An Australian Viewpoint

- Enterprise Application Integration: New Solutions for a Solved Problem or a Challenging Research Field?

- Context Management of ERP Processes in Virtual Communities

- A Hybrid Clustering Technique to Improve Patient Data Quality