Applying the Flow Model to Compensation

| In the following discussion, I will assume three zones of compensation: correct, underpaid, and overpaid. Overpaid means the team member in question is compensated at a level greater than the level at which he or she contributes to the organization. Underpaid means the team member's compensation level is lower than his level of contribution to the organization.[7] We achieve correct compensation when there is a balance between contribution and compensation for the team member in this job, and within this organization; all bets are off relative to other contexts.[8] And clearly, a team member who is just not doing a good job is always, by definition, being overpaid.

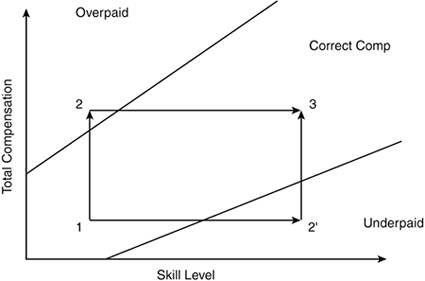

Skills-Based ModelSome organizations compensate by skill level, without considering job difficulty as a dominant factor. This is more common in government organizations and those that focus on seniority, where the assumption is that skills increase with time. Based on the model in Flow, Figure 16.2 depicts this approach. Figure 16.2. Model for skills-based compensation.

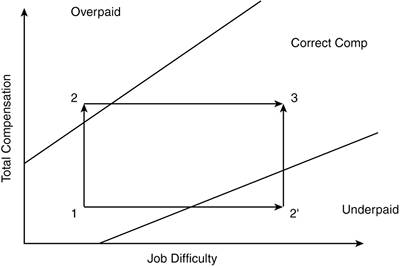

As we see, there is a zone of "correct compensation," where the compensation level is appropriate for the skill set of the team member in the job. Positions 1 and 3 are in this zone, although position 3 is clearly compensated more than position 1. In position 2, the team member is earning more than is appropriate for his or her skill level. This may or may not be dysfunctional; for example, the team member may be doing a difficult job, one that requires more skills than the team member currently has, and is being compensated accordingly. Or, it may just be an error. In position 2', the team member is being underpaid for his or her skill level. Once again, there may be different reasons for this. The team member may be truly underemployed, or the job may not leverage his or her full skill set. Job-Based ModelSome organizations worry less about skill levels and compensate according to the difficulty of the job (or, as a surrogate, responsibility). This model is more typical of entrepreneurial, start-up ventures (see Figure 16.3).[9]

Figure 16.3. Job-based compensation model.

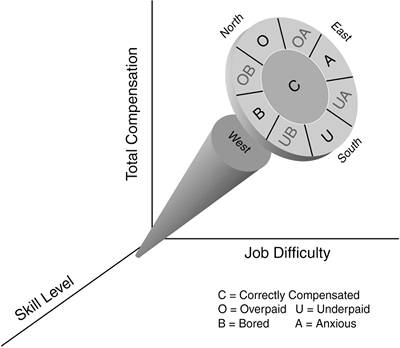

Once again, positions 1 and 3 represent correct compensation, and 3 is more highly compensated than 1. In position 2, the team member is being overpaid relative to the difficulty of the job. This can occur for a variety of reasons. It may be an error, or it may be that the jobholder possesses high-level skills or credentials, but the current job assignment does not make use of those skills. In position 2', the team member is underpaid. This is typical of a person promoted to a new and difficult job who has not yet received a corresponding compensation bump. Note that in this model and the previous one, when someone is at 2, the remedies are to increase either skill level or job difficulty at the current compensation level. When team members are at 2', the appropriate response is to increase compensation. No matter what the model, it is always difficult to move into the "zone" by decreasing job difficulty, skill level, or compensation. Organizations do not usually support downward changes. I will discuss this in more detail later. Introducing the Cone of Correct CompensationI now combine these models into a three-dimensional graph, introducing a Cone of Correct Compensation (see Figure 16.4). Figure 16.4. The Cone of Correct Compensation.

This cone represents the state in which skill levels, job difficulty, and compensation are all in balance. The region inside this cone, indicated by the "C" at the center of the projection, represents the classic "win-win" situation. The team member is neither bored nor anxious; he or she is in the flow channel. Compensation is also correct; the team member is neither underpaid nor overpaid. He or she operates at peak productivity, and the organization is paying a fair price for this. Note that the cone opens up because, as all variables increase, there is more latitude for getting the compensation right.[10]

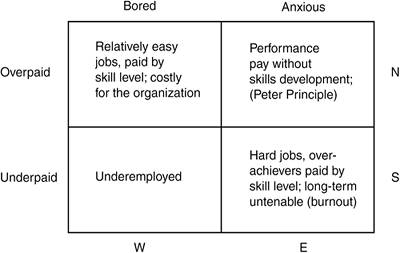

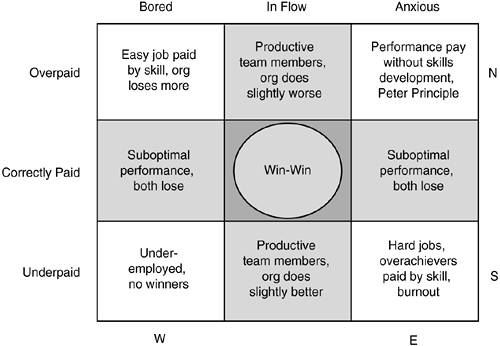

The other eight zones represent "out of cone" scenarios. I have labeled them with compass directions to help navigate through the rest of the discussion. It is possible, although sometimes challenging, to correct the problems in directions E and W. Here, team members are correctly compensated but are either bored or anxious. In these regions, productivity is suboptimal but the issues involve a skills/difficulty mismatch, so fiddling with compensation doesn't help. The issues in the N and S directions are relatively simple to deal with. In this case, the team member is in the flow channel but is either underpaid or overpaid. An adjustment needs to be made to bring the equation back into balance, so that neither the team member nor the organization profits excessively from the team member being in the flow channel. We will discuss the other four directions, which are somewhat more pathological, in the next section. After that, I will consider in greater detail the E, W and N, S scenarios I just described. In both discussions, I take the projection of the cone and depict it as a two-dimensional plot. The four diagonal cases become a two-by-two plot in the next section; after that, the center and eight compass directions become a three-by-three plot. Diagonal CasesThis section focuses on the four extreme cases that involve team members who are in the wrong jobs and incorrectly compensated. These fall at the four diagonal corners of the coneNE, NW, SE, and SW, respectively, as represented in Figure 16.5. Figure 16.5. Team members who are in the wrong jobs and incorrectly compensated.

Please note that team members may be "incorrectly compensated" for many reasons, including historical errors, temporary disequilibria in the marketplace between supply and demand of specialized skill sets, and so on. The upper-left box (NW) contains team members who are being paid for their skill level but are doing relatively easy jobs that could be filled at lower cost to the organization by less skilled team members. This is a bad box: Productivity is intrinsically low relative to pay, and there is an opportunity cost to the organization because it does not exploit these team members' full potential. The lower-left box (SW) represents the bored, underpaid team members of the world. They are at least marginally qualified, have relatively easy jobs, and are not paid a lot. Sometimes the combination of boredom and lack of compensation spurs them to seek other opportunities; often they vegetate. This class represents a waste of human capital. Some civil service workers fit into this category.[11]

The lower-right box (SE) contains the strivers in the organization: those who are doing hard jobs with relatively inadequate skills, and being underpaid in the bargain. This combination is untenable in the long term, as these team members will burn out sooner or later. Finally, the upper-right box (NE) represents team members who are being overpaid for being overextended. They may do well temporarily but ultimately will fail unless they get some skills development. As there is a strong monetary incentive for them to continue to "get in over their heads," they are great candidates for proving the Peter Principle.[12]

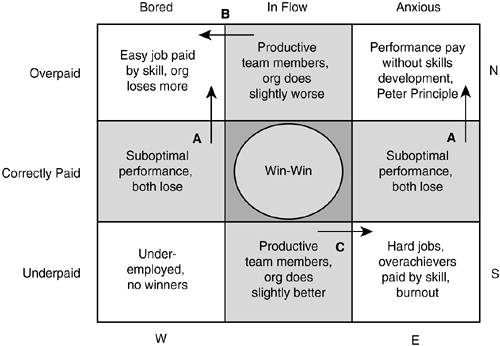

The Nine PossibilitiesIn Figure 16.6, I consider all nine possible cases for our cone model, not just the four most pathological cases I showed in Figure 16.5. Figure 16.6. Nine possibilities in and around the Cone of Correct Compensation.

Here the cone of correct compensation is depicted by the center bulls-eye, where flow has been achieved and the compensation level is just right. In this case, the team member is happy and productive, and the organization is getting the best productivity at a fair price. In the middle row left and right (E and W), compensation is fair, but both the team member and the organization lose, because productivity is suboptimal. In this case, tinkering with compensation does nothing to address the problems that cause team member unhappiness and organizational loss of productivity. This is a pure difficulty/skills mismatch and needs to be addressed along those axes. In the middle column, top and bottom (N and S), the team member is in flow, and productivity is maximized. Compensation should be adjusted to ensure that neither the team member nor the organization profits excessively from that situation. Clearly, this is easy to do for the underpaid case; for the overpaid case, we usually hold compensation constant while increasing both of the other variables (job difficulty and skill level) in balance. The four corner cases were discussed in the previous section. In the next section, I will discuss the stability of these various states, along with actions that managers can take to get team members and the organization to a win-win state. Instability of North, South, East, and WestWe know that the center in the previous figure represents an optimal condition, and once a team member is there, we need to continue to move him or her along the "body diagonal" of the cone to keep him or her in the region of correct compensation. We also know that the four corners are potential sink states, or places where things either degenerate rapidly or are long-term costly to the team member and/or organization. Are the four middle states stable? Although they are not as dangerous as the corner states, the problem is that they tend not to be stable over the long term if left unattended (see Figure 16.7). Figure 16.7. Unattended middle states move toward corners.

In both cases in the middle row (E and W), the correctly paid team member who is not in a state of flow will become less and less productive because of either anxiety or boredom. At some point, he or she will migrate upward on the chart, as indicated by the arrows labeled "A," moving into the overpaid category. This will happen without any nominal rise in compensation; it is strictly the effect of becoming less productive at constant compensation. We have observed that in-flow team members who are overpaid (N) tend to get bored. This makes them less productive and moves them into the NW corner, as indicated by the arrow labeled "B." I have also observed that in-flow team members who are underpaid (S) tend to become anxious as a result of the inequity they see in their compensation. This has a tendency to throw them out of flow and into the SE corner, as indicated by the arrow labeled "C." (As they become less productive, they also become less underpaid.) Getting to Win-WinA good management objective is to get all team members to the win-win area inside the cone and to keep them there. Most organizations do not have the flexibility to easily reduce team members' job difficulty, nor are they likely to want (or be able) to reduce compensation. It is also meaningless to talk about reducing skill levels as a way to achieve equilibrium,[13] although sometimes a lateral move may have that effectin other words, some of the team member's current skill set may be inapplicable in the new position, and new skills will have to be developed. But usually the only way to address an imbalance is by moving other variables in a positive direction, as opposed to changing things in a negative direction.

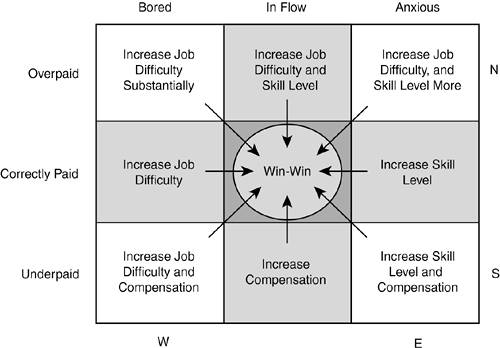

Most of the recommended remedies shown in Figure 16.8 are self-explanatory, but we'll examine a few special cases. Figure 16.8. Getting to win-win.

In the NW corner, the only remedy is to dramatically increase either job difficulty or responsibility. The team member has the skills and is already being paid for a more difficult challenge. In the N box, care must be taken to increase skill level and job difficulty in proportion so as to not violently throw the team member out of flow. In the NE box, skills must be increased more than the increase in job difficulty, else disaster looms. Increasing skill level is tricky. It usually cannot be done overnight and may involve training, coaching, mentoring, and other methods that require time. Team members who have potential but need skills improvement need to be identified early, so that remedial action can be taken before the situation becomes so acute that the improvement cannot take place within a reasonable timeframe. Note that of the eight suboptimal cases, only one can be addressed by solely increasing compensation. Five cases require no compensation action but do require adjustment of skill levels and job difficulty to get back into the cone. The remaining two cases require adjusting either skill levels or job difficulty in combination with compensation. So, remarkably, compensation is a partial remedy in only three out of the eight dysfunctional situations. Mapping Current Team MembersIf you are managing a team, do the following experiment. Lay out the three-by-three grid with "Win-Win" in the middle, and then assign each team member to one of the nine boxes. You will find yourself thinking about people in ways you have not previously considered. You may find people with otherwise different backgrounds clustered in the same box. After you have finished the allocation, you will have some idea of both the development plan and the compensation strategy for each class. The exercise forces you to look at both aspects at the same time, something we sometimes forget to do. This methodology also makes discussions with team members more constructive, as you can show them that you have considered all the variables as you figure out their path forward. Mapping New Team MembersWhen recruiting in a tight labor market, we sometimes have to pay somewhat more for a new hire than we would like. Equity vis à vis current team members becomes an issue. And sometimes making an attractive offer involves improving the prospective team member's situation relative to the one he already has, which may be the result of an aberration in his current organization. One way to approach such situations is to lay out your current roster on the grid and see where the new player will fit. If it becomes clear that the salary inequity will cause not only an immediate problem but also long-term development problems, then perhaps you need to reconsider your offer. |

EAN: N/A

Pages: 269