Section 19.8. PyForm: A Persistent Object Viewer

19.8. PyForm: A Persistent Object ViewerInstead of going into additional database interface details that are freely available at Python.org, I'm going to close out this chapter by showing you one way to combine the GUI technology we met earlier in the text with the persistence techniques introduced in this chapter. This section presents PyForm, a Tkinter GUI designed to let you browse and edit tables of records:

Although this example is about GUIs and persistence, it also illustrates Python design techniques. To keep its implementation both simple and type-independent, the PyForm GUI is coded to expect tables to look like dictionaries of dictionaries. To support a variety of table and record types, PyForm relies on separate wrapper classes to translate tables and records to the expected protocol:

The net effect is that PyForm can be used to browse and edit a wide variety of table types, despite its dictionary interface expectations. When PyForm browses shelves and DBM files, table changes made within the GUI are persistentthey are saved in the underlying files. When used to browse a shelve of class instances, PyForm essentially becomes a GUI frontend to a simple object database that is built using standard Python persistence tools. 19.8.1. Processing Shelves with CodeBefore we get to the GUI, though, let's see why you'd want one in the first place. To experiment with shelves in general, I first coded a canned test datafile. The script in Example 19-19 hardcodes a dictionary used to populate databases (cast), as well as a class used to populate shelves of class instances (Actor). Example 19-19. PP3E\Dbase\testdata.py

The cast object here is intended to represent a table of records (it's really a dictionary of dictionaries when written out in Python syntax like this). Now, given this test data, it's easy to populate a shelve with cast dictionaries. Simply open a shelve and copy over cast, key for key, as shown in Example 19-20. Example 19-20. PP3E\Dbase\castinit.py

Once you've done that, it's almost as easy to verify your work with a script that prints the contents of the shelve, as shown in Example 19-21. Example 19-21. PP3E\Dbase\castdump.py

Here are these two scripts in action, populating and displaying a shelve of dictionaries: ...\PP3E\Dbase>python castinit.py ...\PP3E\Dbase>python castdump.py alan {'job': 'comedian', 'name': ('Alan', 'B')} mel {'job': 'producer', 'name': ('Mel', 'C')} buddy {'spouse': 'Pickles', 'job': 'writer', 'name': ('Buddy', 'S')} sally {'job': 'writer', 'name': ('Sally', 'R')} rob {'spouse': 'Laura', 'job': 'writer', 'name': ('Rob', 'P')} milly {'spouse': 'Jerry', 'name': ('Milly', '?'), 'kids': 2} laura {'spouse': 'Rob', 'name': ('Laura', 'P'), 'kids': 1} So far, so good; but here is where you reach the limitations of manual shelve processing: to modify a shelve you need much more general tools. You could write little Python scripts that each perform very specific updates. Or you might even get by for awhile typing such update commands by hand in the interactive interpreter: >>> import shelve >>> db = shelve.open('data/castfile') >>> rec = db['rob'] >>> rec['job'] = 'hacker' >>> db['rob'] = rec For all but the most trivial databases, though, this will get tedious in a hurryespecially for a system's end users. What you'd really like is a GUI that lets you view and edit shelves arbitrarily, and that can be started up easily from other programs and scripts, as shown in Example 19-22. Example 19-22. PP3E\Dbase\castview.py

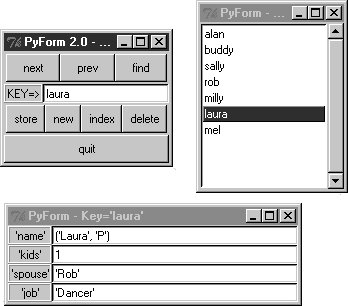

To make this particular script work, we need to move on to the next section. 19.8.2. Adding a Graphical InterfaceThe path traced in the last section really is what led me to write PyForm, a GUI tool for editing arbitrary tables of records. When those tables are shelves and DBM files, the data PyForm displays is persistent; it lives beyond the GUI's lifetime. Because of that, PyForm can be seen as a simple database browser. We've already met all the GUI interfaces PyForm uses earlier in this book, so I won't go into all of its implementation details here (see the chapters in Part III for background details). Before we see the code at all, though, let's see what it does. Figure 19-1 shows PyForm in action on Windows, browsing a shelve of persistent instance objects, created from the testdata module's Actor class. It looks slightly different but works the same on Linux and Macs. Figure 19-1. PyForm displaying a shelve of Actor objects PyForm uses a three-window interface to the table being browsed; all windows are packed for proper window expansion and clipping, as set by the rules we studied earlier in this book. The window in the upper left of Figure 19-1 is the main window, created when PyForm starts; it has buttons for navigating through a table, finding items by key, and updating, creating, and deleting records (more useful when browsing tables that persist between runs). The table (dictionary) key of the record currently displayed shows up in the input field in the middle of this window. The "index" button pops up the listbox window in the upper right, and selecting a record in either window at the top creates the form window at the bottom. The form window is used both to display a record and to edit itif you change field values and press "store," the record is updated. Pressing "new" clears the form for input of new values (fill in the Key=> field and press "store" to save the new record). Field values are typed with Python syntax, so strings are quoted (more on this later). When browsing a table with records that contain different sets of field names, PyForm erases and redraws the form window for new field sets as new records are selected. To avoid seeing the window re-created, use the same format for all records within a given table. 19.8.3. PyForm GUI ImplementationOn to the code; the first thing I did when writing PyForm was to code utility functions to hide some of the details of widget creation. By making a few simplifying assumptions (e.g., packing protocol), the module in Example 19-23 helps keep some GUI coding details out of the rest of the PyForm implementation. Example 19-23. PP3E\Dbase\TableBrowser\guitools.py

Armed with this utility module, the file in Example 19-24 implements the rest of the PyForm GUI. It uses the GuiMixin module we wrote in Chapter 11, for simple access to standard pop-up dialogs. It's also coded as a class that can be specialized in subclasses or attached to a larger GUI. I run PyForm as a standalone program. Attaching its FormGui class really attaches its main window only, but it can be used to provide a precoded table browser widget for other GUIs. This file's FormGui class creates the GUI shown in Figure 19-1 and responds to user interaction in all three of the interface's windows. Because we've already covered all the GUI tools that PyForm uses, you should study this module's source code listing for additional implementation details. Notice, though, that this file knows almost nothing about the table being browsed, other than that it looks and feels like a dictionary of dictionaries. To understand how PyForm supports browsing things such as shelves of class instances, you will need to look elsewhere (or at least wait for the next module). Example 19-24. PP3E\Dbase\TableBrowser\formgui.py

The file's self-test code starts up the PyForm GUI to browse the in-memory dictionary of dictionaries called "cast" in the testdata module listed earlier. To start PyForm, you simply make and run the FormGui class object this file defines, passing in the table to be browsed. Here are the messages that show up in stdout after running this file and editing a few entries displayed in the GUI; the dictionary is displayed on GUI startup and exit: ...\PP3E\Dbase\TableBrowser>python formgui.py alan {'job': 'comedian', 'name': ('Alan', 'B')} sally {'job': 'writer', 'name': ('Sally', 'R')} rob {'spouse': 'Laura', 'job': 'writer', 'name': ('Rob', 'P')} mel {'job': 'producer', 'name': ('Mel', 'C')} milly {'spouse': 'Jerry', 'name': ('Milly', '?'), 'kids': 2} buddy {'spouse': 'Pickles', 'job': 'writer', 'name': ('Buddy', 'S')} laura {'spouse': 'Rob', 'name': ('Laura', 'P'), 'kids': 1} alan {'job': 'comedian', 'name': ('Alan', 'B')} jerry {'spouse': 'Milly', 'name': 'Jerry', 'kids': 0} sally {'job': 'writer', 'name': ('Sally', 'R')} rob {'spouse': 'Laura', 'job': 'writer', 'name': ('Rob', 'P')} mel {'job': 'producer', 'name': ('Mel', 'C')} milly {'spouse': 'Jerry', 'name': ('Milly', '?'), 'kids': 2} buddy {'spouse': 'Pickles', 'job': 'writer', 'name': ('Buddy', 'S')} laura {'name': ('Laura', 'P'), 'kids': 3, 'spouse': 'bob'} The last line represents a change made in the GUI. Since this is an in-memory table, changes made in the GUI are not retained (dictionaries are not persistent by themselves). To see how to use the PyForm GUI on persistent stores such as DBM files and shelves, we need to move on to the next topic. 19.8.4. PyForm Table WrappersThe following file defines generic classes that "wrap" (interface with) various kinds of tables for use in PyForm. It's what makes PyForm useful for a variety of table types. The prior module was coded to handle GUI chores, and it assumes that tables expose a dictionary-of-dictionaries interface. Conversely, this next module knows nothing about the GUI but provides the translations necessary to browse nondictionary objects in PyForm. In fact, this module doesn't even import Tkinter at allit deals strictly in object protocol conversions and nothing else. Because PyForm's implementation is divided into functionally distinct modules like this, it's easier to focus on each module's task in isolation. Here is the hook between the two modules: for special kinds of tables, PyForm's FormGui is passed an instance of the Table class coded here. The Table class intercepts table index fetch and assignment operations and uses an embedded record wrapper class to convert records to and from dictionary format as needed. For example, because DBM files can store only strings, Table converts real dictionaries to and from their printable string representation on table stores and fetches. For class instances, Table exTRacts the object's _ _dict_ _ attribute dictionary on fetches and copies a dictionary's fields to attributes of a newly generated class instance on stores.[*] The end result is that the GUI thinks the table is all dictionaries, even if it is really something very different here.

While you study this module's listing, shown in Example 19-25, notice that there is nothing here about the record formats of any particular database. In fact, there was none in the GUI-related formgui module either. Because neither module cares about the structure of fields used for database records, both can be used to browse arbitrary records. Example 19-25. PP3E\Dbase\formtable.py

Besides the Table and record-wrapper classes, the module defines generator functions (e.g., ShelveOfInstance) that create a Table for all reasonable table and record combinations. Not all combinations are validDBM files, for example, can contain only dictionaries coded as strings because class instances don't easily map to the string value format expected by DBM. However, these classes are flexible enough to allow additional Table configurations to be introduced. The only thing that is GUI related about this file at all is its self-test code at the end. When run as a script, this module starts a PyForm GUI to browse and edit either a shelve of persistent Actor class instances or a DBM file of dictionaries, by passing in the right kind of Table object. The GUI looks like the one we saw in Figure 19-1 earlier; when run without arguments, the self-test code lets you browse a shelve of class instances: ...\PP3E\Dbase\TableBrowser>python formtable.py shelve-of-instance test ...display of contents on exit... Because PyForm displays a shelve this time, any changes you make are retained after the GUI exits. To reinitialize the shelve from the cast dictionary in testdata, pass a second argument of 1 (0 means don't reinitialize the shelve). To override the script's default shelve filename, pass a different name as a third argument: ...\PP3E\Dbase\TableBrowser>python formtable.py shelve 1 ...\PP3E\Dbase\TableBrowser>python formtable.py shelve 0 ../data/shelve1 To instead test PyForm on a DBM file of dictionaries mapped to strings, pass a dbm in the first command-line argument; the next two arguments work the same: ...\PP3E\Dbase\TableBrowser>python formtable.py dbm 1 ..\data\dbm1 dbm-of-dictstring test ...display of contents on exit... Finally, because these self-tests ultimately process concrete shelve and DBM files, you can manually open and inspect their contents using normal library calls. Here is what they look like when opened in an interactive session: ...\PP3E\Dbase\data>ls dbm1 myfile shelve1 ...\PP3E\Dbase\data>python >>> import shelve >>> db = shelve.open('shelve1') >>> db.keys( ) ['alan', 'buddy', 'sally', 'rob', 'milly', 'laura', 'mel'] >>> db['laura'] <PP3E.Dbase.testdata.Actor instance at 799850> >>> import anydbm >>> db = anydbm.open('dbm1') >>> db.keys( ) ['alan', 'mel', 'buddy', 'sally', 'rob', 'milly', 'laura'] >>> db['laura'] "{'name': ('Laura', 'P'), 'kids': 2, 'spouse': 'Rob'}" The shelve file contains real Actor class instance objects, and the DBM file holds dictionaries converted to strings. Both formats are retained in these files between GUI runs and are converted back to dictionaries for later redisplay.[*]

19.8.5. PyForm Creation and View Utility ScriptsThe formtable module's self-test code proves that it works, but it is limited to canned test-case files and classes. What about using PyForm for other kinds of databases that store more useful kinds of data? Luckily, both the formgui and the formtable modules are written to be genericthey are independent of a particular database's record format. Because of that, it's easy to point PyForm to databases of your own; simply import and run the FormGui object with the (possibly wrapped) table you wish to browse. The required startup calls are not too complex, and you could type them at the interactive prompt every time you want to browse a database; but it's usually easier to store them in scripts so that they can be reused. The script in Example 19-26, for example, can be run to open PyForm on any shelve containing records stored in class instance or dictionary format. Example 19-26. PP3E\Dbase\dbview.py

The only catch here is that PyForm doesn't handle completely empty tables very well; there is no way to add new records within the GUI unless a record is already present. That is, PyForm has no record layout design tool; its "new" button simply clears an existing input form. Because of that, to start a new database from scratch, you need to add an initial record that gives PyForm the field layout. Again, this requires only a few lines of code that could be typed interactively, but why not instead put it in generalized scripts for reuse? The file in Example 19-27 shows one way to go about initializing a PyForm database with a first empty record. Example 19-27. PP3E\Dbase\dbinit1.py

Now, simply change some of this script's settings or pass in command-line arguments to generate a new shelve-based database for use in PyForm. You can substitute any fields list or class name in this script to maintain a simple object database with PyForm that keeps track of real-world information (we'll see two such databases in action in a moment). The empty record created by this script shows up with the key ?empty? when you first browse the database in PyForm with dbview; replace it with a first real record using the PyForm store key, and you are in business. As long as you don't change the database's shelve outside of the GUI, all of its records will have the same fields format, as defined in the initialization script. But notice that the dbinit1 script goes straight to the shelve file to store the first record; that's fine today, but it might break if PyForm is ever changed to do something more custom with its stored data representation. Perhaps a better way to populate tables outside the GUI is to use the Table wrapper classes it employs. The following alternative script, for instance, initializes a PyForm database with generated Table objects, not direct shelve operations (see Example 19-28). Example 19-28. PP3E\Dbase\dbinit2.py

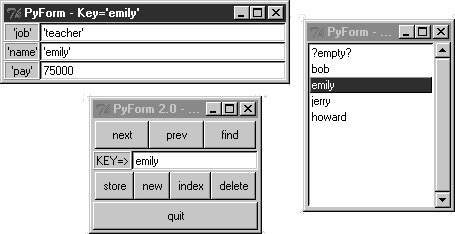

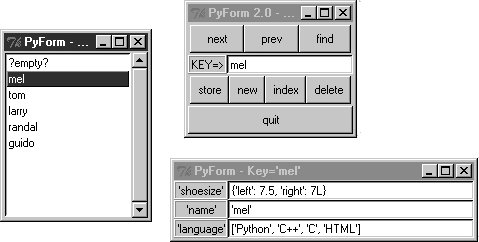

19.8.5.1. Creating and browsing custom databasesLet's put the prior section's scripts to work to initialize and edit a couple of custom databases. Figure 19-2 shows one being browsed after initializing the database with a script and adding a handful of real records within the GUI. Figure 19-2. A shelve of Person objects (dbinit1, dbview) The listbox here shows the record I added to the shelve within the GUI. I ran the following commands to initialize the database with a starter record and to open it in PyForm to add records (that is, Person class instances): ...\PP3E\Dbase\TableBrowser>python dbinit1.py ...\PP3E\Dbase\TableBrowser>python dbview.py You can tweak the class name or fields dictionary in the dbinit scripts to initialize records for any sort of database you care to maintain with PyForm; use dictionaries if you don't want to represent persistent objects with classes (but classes let you add other sorts of behavior as methods not visible under PyForm). Be sure to use a distinct filename for each database; the initial ?empty? record can be deleted as soon as you add a real entry (later, simply select an entry from the listbox and press "new" to clear the form for input of a new record's values). The data displayed in the GUI represents a true shelve of persistent Person class instance objectschanges and additions made in the GUI will be retained for the next time you view this shelve with PyForm. If you like to type, though, you can still open the shelve directly to check PyForm's work: ...\PP3E\Dbase\data>ls mydbase-class myfile shelve1 ...\PP3E\Dbase\data>python >>> import shelve >>> db = shelve.open('mydbase-class') >>> db.keys( ) ['emily', 'jerry', '?empty?', 'bob', 'howard'] >>> db['bob'] <PP3E.Dbase.person.Person instance at 798d70> >>> db['emily'].job 'teacher' >>> db['bob'].tax 30000.0 Notice that bob is an instance of the Person class we met earlier in this chapter (see the section "Shelve Files"). Assuming that the person module is still the version that introduced a _ _getattr_ _ method, asking for a shelved object's tax attribute computes a value on the fly because this really invokes a class method. Also note that this works even though Person was never imported herePython loads the class internally when re-creating its shelved instances. You can just as easily base a PyForm-compatible database on an internal dictionary structure, instead of on classes. Figure 19-3 shows one being browse after being initialized with a script and populated with the GUI. Figure 19-3. A shelve of dictionaries (dbinit2, dbview) Besides its different internal format, this database has a different record structure (its record's field names differ from the last example), and it is stored in a shelve file of its own. Here are the commands I used to initialize and edit this database: ...\PP3E\Dbase\TableBrowser>python dbinit2.py ../data/mydbase-dict dict ...\PP3E\Dbase\TableBrowser>python dbview.py ../data/mydbase-dict dict After adding a few records (that is, dictionaries) to the shelve, you can either view them again in PyForm or open the shelve manually to verify PyForm's work: ...\PP3E\Dbase\data>ls mydbase-class mydbase-dict myfile shelve1 ...\PP3E\Dbase\data>python >>> db = shelve.open('mydbase-dict') >>> db.keys( ) ['tom', 'guido', '?empty?', 'larry', 'randal', 'mel'] >>> db['guido'] {'shoesize': 42, 'name': 'benevolent dictator', 'language': 'Python'} >>> db['mel']['shoesize'] {'left': 7.5, 'right': 7L} This time, shelve entries are really dictionaries, not instances of a class or converted strings. PyForm doesn't care, thoughbecause all tables are wrapped to conform to PyForm's interface, both formats look the same when browsed in the GUI. 19.8.6. Data as CodeNotice that the shoesize and language fields in the screenshot in Figure 19-3 really are a dictionary and a list. You can type any Python expression syntax into this GUI's form fields to give values (that's why strings are quoted there). PyForm uses the Python built-in repr function to convert value objects for display (repr(x) is like the older 'x' expression and is similar to str(x) but yields an as-code display that adds quotes around strings). To convert from a string back to value objects, PyForm uses the Python eval function to parse and evaluate the code typed into fields. The key entry/display field in the main window does not add or accept quotes around the key string because keys must still be strings in things such as shelves (even though fields can be arbitrary types). As we've seen at various points in this book, eval (and its statement cousin, exec) is powerful but dangerousyou never know when a user might type something that removes files, hangs the system, emails your boss, and so on. If you can't be sure that field values won't contain harmful code (whether malicious or otherwise), use the rexec restricted execution mode tools we met in Chapter 18 to evaluate strings. Alternatively, you can simply limit the kinds of expressions allowed and evaluate them with simpler tools (e.g., int, str) or store all data as strings. 19.8.7. Browsing Other Kinds of Objects with PyFormAlthough PyForm expects to find a dictionary-of-dictionary interface (protocol) in the tables it browses, a surprising number of objects fit this mold because dictionaries are so pervasive in Python object internals. In fact, PyForm can be used to browse things that have nothing to do with the notion of database tables of records at all, as long as they can be made to conform to the protocol. For instance, the Python sys.modules table we met in Chapter 3 is a built-in dictionary of loaded module objects. With an appropriate wrapper class to make modules look like dictionaries, there's no reason we can't browse the in-memory sys.modules with PyForm too, as shown in Example 19-29. Example 19-29. PP3E\Dbase\TableBrowser\viewsysmod.py

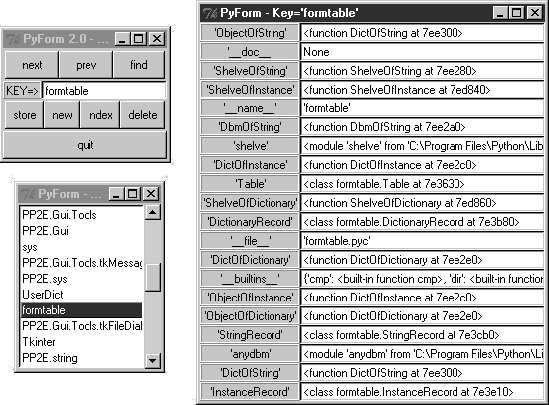

This script defines a class to pull out a module's _ _dict_ _ attribute dictionary (formtable's InstanceRecord won't do, because it also looks for a _ _class_ _). The rest of it simply passes sys.modules to PyForm (FormGui) wrapped in a Table object; the result appears in Figure 19-4. Figure 19-4. FormGui browsing sys.modules (viewsysmod) With similar record and table wrappers, all sorts of objects could be viewed in PyForm. As usual in Python, all that matters is that they provide a compatible interface. 19.8.8. Browsing Other Kinds of Databases with PyFormIn fact, with just a little creativity, we could also write table wrappers that allow the PyForm GUI to view objects in ZODB databases and records in SQL databases third-party systems we studied earlier in this chapter:

In deference to space, we'll leave the second of these extensions as a suggested exercise. The first is straightforward: Example 19-30 launches the PyForm GUI to browse the ZODB people database we used as an example earlier in this chapter. This script worksit allows you to use the GUI to browse and update persistent class instances stored in a ZODB object databasebut it suffers from some innate limitations in the GUI's design. As coded, PyForm doesn't support instances of more than one class in the database, and it has no way to call class methods. More subtly, PyForm assumes that instances either are created from a class with no nondefault constructor arguments or support _ _class_ _ attribute assignments (its code tries both schemes to re-create the instance from its dictionary-based representation). The former of these constraints was not coded in the original class, and the latter did not work for classes derived from ZODB persistence classes when this script was tested. Because of these constraints, the test script in Example 19-30 uses an empty class to initialize the database: since methods and derived subclasses aren't yet supported, classes in PyForm are little more than flat attribute namespaces. As currently coded, PyForm does not leverage the full power of Python classesany methods they contain may still be called by code outside the context of the PyForm GUI, but they have no purpose within it. We'll explore some of these design issues in more detail in the next section. Perhaps just as remarkable as its flaws, though, is the fact that PyForm can be used on a ZODB database at allby encapsulating the database behind a common object interface, it supports any conforming object. Example 19-30. PP3E\Database\ZODBscripts\viewzodb.py

Run this code on your machine to see its windowsthey are exactly like those we've seen before, but the records browsed are objects that reside in a ZODB database instead of a shelve. 19.8.9. PyForm LimitationsAlthough the sys.modules and ZODB viewer scripts of the last two sections work, they highlight a few limitations of PyForm's current design:

The last item in the preceding list is a subtle design point, and it merits some addition explanation. PyForm current overloads table index fetch and assignment, and the GUI internally uses dictionaries to represent records. Fetches assume a dictionary-like object comes back, and stores make a new dictionary object (or use the current one), fill it out, and pass it off to the Table wrapper for conversion to the table's underlying record implementation. When browsing tables of instances, the fetch conversion is trivial (we use the instance's _ _dict_ _ directly), but stores must create and fill out a new instance. It would be almost as easy to overload record field index fetch and assignment instead, to avoid converting dictionaries to instances, and possibly avoid the Table wrapper layer. In this scheme, records held in PyForm might be whatever object the table stores (not necessarily dictionaries), and each record field fetch or assignment in PyForm would be routed back to record wrapper classes. For example, by wrapping instance records in a class that maps dictionary field indexing to class attributes with _ _getitem_ _ and _ _setitem_ _ overload methods, the GUI might browse actual class instance objects. These two overload methods would simply call the getattr and setattr built-in functions to access the attribute corresponding to the key by string name, and the keys call in the GUI used to extract field names could be mapped by the record wrapper to the instance _ _dict_ _. The trickiest part of this scheme is that the GUI would have to know how to make a new empty record before filling its fieldsthis would likely require that the GUI have knowledge of the concrete type of the record (dictionary or instance, as well as the class if it is an instance) or use of a Table wrapper with a customizable method for creating a new empty record. By building and filling dictionaries, the GUI currently finesses this issue completely and delegates it to the customized table and record wrappers. There are also a few substantial downsides to this approach. For one, PyForm could not browse any instance object unless it inherits from the record wrapper class or is wrapped up in one automatically by a Table interface class on fetches and stores. For another, Table also has some additional interfaces not provided by shelves, which we have to code elsewhere. This scheme might also preclude use of indexing overload methods in the record class itself, though the GUI itself does not support such operations anyhow. Most significantly, this model would not transparently handle other use cases, such as string-based records. Cases requiring conversion with eval and str, for instance, would not fit the new model at allDBM files that map whole records to strings might require complex special case logic to handle field-at-a-time requests or fall back to converting from and to dictionaries on fetches and stores, as is currently done. Because of such exceptions, we would probably wind up with a Table wrapper anyhow, unless we limit the GUI's use cases. Generating a new empty record just by itself varies so much per record kind that we need a class hierarchy to customize the operation. In the end, it may be easier to use dictionaries in all cases and convert from that where needed, as PyForm currently does. In other words, there is room for improvement if you care to experiment. On the other hand, extensions in this domain are somewhat open-ended, so we'll leave them as suggested exercises. PyForm was designed to view mappings of mappings and was never meant to be a general Python object viewer. But as a simple GUI for tables of persistent objects, it meets its design goals as planned. Python's shelves and classes make such systems both easy to code and powerful to use. Complex data can be stored and fetched in a single step, as well as augmented with methods that provide dynamic record behavior. As an added bonus, by programming such programs in Python and Tkinter, they are automatically portable among all major GUI platforms. When you mix Python persistence and GUIs, you get a lot of features "for free." |