Section 18.7. Windows Web Scripting Extensions

18.7. Windows Web Scripting ExtensionsAlthough this book doesn't cover the Windows-specific extensions available for Python in detail, a quick look at Internet scripting tools available to Windows programmers is in order here. On Windows, Python can be used as a scripting language for both the Active Scripting and the Active Server Pages systems, which provide client- and server-side control of HTML-based applications. More generally, Python programs can also take the role of COM and DCOM clients and servers on Windows. The .NET framework provides additional options for Python programmers. This section is largely Microsoft specificif you are interested in portability, other systems in this chapter may address your needs better (see Jython's client-side applets, PSP's server-side scripting support, and Zope's server-side object publishing model). On the other hand, if portability isn't a concern, the following techniques provide powerful ways to script both sides of a web conversation with Python. 18.7.1. Active Scripting: Client-Side EmbeddingActive Scriptingsometimes known as ActiveX Scripting, or just ActiveXis a technology that allows scripting languages to communicate with hosting applications. The hosting application provides an application-specific object model API, which exposes objects and functions for use in the scripting language programs. In one of its more common roles, Active Scripting provides support that allows scripting language code embedded in HTML pages to communicate with the local web browser through an automatically exposed object model API. Internet Explorer, for instance, utilizes Active Scripting to export things such as global functions and user-interface objects, for use in scripts embedded in HTML that are run on the client. With Active Scripting, Python code may be embedded in a web page's HTML between special tags; such code is executed on the client machine and serves the same roles as embedded JavaScript and VBScript.

18.7.1.1. Active Scripting basicsEmbedding Python in client-side HTML works only on machines where Python is installed and Internet Explorer is configured to know about the Python language. Because of that, this technology doesn't apply to most of the browsers in cyberspace today. On the other hand, if you can configure the machines on which a system is to be delivered, this is a nonissue. Before we get into a Python example, let's look at the way standard browser installations handle other languages embedded in HTML. By default, Internet Explorer knows about JavaScript (really, Microsoft's Jscript implementation of it) and VBScript (a Visual Basic derivative), so you can embed both of those languages in any delivery scenario. For instance, the HTML file in Example 18-12 embeds JavaScript code, the default Internet Explorer scripting language on my PC. Example 18-12. PP3E\Internet\Other\Win\activescript-js.html

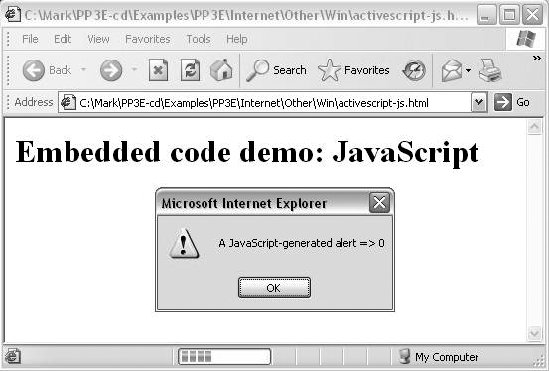

All the text between the <SCRIPT> and </SCRIPT> tags in this file is JavaScript code. Don't worry about its syntaxthis book isn't about JavaScript. The important thing to know is how this code is used by the browser. When a browser detects a block of code like this while building up a new page, it strips out the code, locates the appropriate interpreter, tells the interpreter about global object names, and passes the code to the interpreter for execution. The global names become variables in the embedded code and provide links to browser context. For instance, the name alert in the code block refers to a global function that creates a message box. Other global names refer to objects that give access to the browser's user interface: window objects, document objects, and so on. You can run this HTML file on the local machine by clicking on its name in a file explorer. It can also be stored on a remote server and accessed via its URL in a browser. Whichever way you start it, three pop-up alert boxes created by the embedded code appear during page construction. Figure 18-9 shows one under Internet Explorer. Figure 18-9. Internet Explorer running embedded JavaScript code 18.7.1.2. Embedding Python in HTMLSo how about putting Python code in that page, then? Alas, we need to do a bit more first. Although Internet Explorer is language neutral in principle, it does support some languages better than others, at least today. Moreover, other browsers may be more rigid and may not support the Active Scripting concept at all. To make the Python version work, you must do more than simply installing Python on your PC. You must also install the PyWin32 package separately and run its tools to register Python to Internet Explorer. The PyWin32 package includes the win32com extensions for Python, plus the PythonWin IDE (a GUI for editing and running Python programs, written with the MFC interfaces in PyWin32) and many other Windows-specific tools not covered in this book. In the past, registering Python for use in Internet Explorer was either an automatic side-effect of installing PyWin32 or was achieved by running a script located in the Windows extension's code in Lib\site-packages of the Python install tree, named win32comext\axscript\client\pyscript.py. Because this package changes over time, though, see its documentation for current registration details. Once you've registered Python with Internet Explorer, Python code embedded in HTML works just like our JavaScript exampleInternet Explorer presets Python global names to expose its object model and passes the embedded code to your Python interpreter for execution. Example 18-13 shows our alerts example again, programmed with embedded Python code. Example 18-13. PP3E\Internet\Other\Win\activescript-py.html

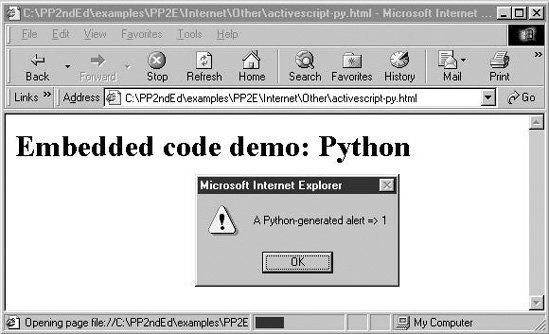

Figure 18-10 shows one of the three pop ups you should see when you open this file in Internet Explorer after installing PyWin32 and registering Python to Internet Explorer. Note that the first time you access this page, Internet Explorer may need to load Python, which could induce an apparent delay on slower machines; later accesses generally start up much faster because Python has already been loaded. Figure 18-10. Internet Explorer running embedded Python code (currently disabled) With a simple configuration step, Python code can be embedded in HTML and be made to run under Internet Explorer, just like JavaScript and VBScript. Although this works on only some browsers and platforms, for many applications, the portability constraint is acceptable. Active Scripting is a straightforward way to add client-side Python scripting for web browsers, especially when you can control the target delivery environment. For instance, machines running on an intranet within a company may have well-known configurations. In such scenarios, Active Scripting lets developers apply all the power of Python in their client-side scripts. 18.7.2. Active Server Pages: Server-Side EmbeddingActive Server Pages (ASPs) use a similar model: Python code is embedded in the HTML that defines a web page. But ASP is a server-side technologyembedded Python code runs on the server machine and uses an object-based API to dynamically generate portions of the HTML that is ultimately sent back to the client-side browser. As we saw in the last two chapters, Python server-side CGI scripts embed and generate HTML, and they deal with raw inputs and output streams. By contrast, server-side ASP scripts are embedded in HTML and use a higher-level object model to get their work done. Just like client-side Active Scripting, ASP requires you to install Python and the Python Windows PyWin32 extensions package. But because ASP runs embedded code on the server, you need to configure Python only on one machine. Like CGI scripts in general, this generally makes Python ASP scripting much more widely applicable, as you don't need Python support on every client. Moreover, because you control the content of the embedded code on your server, this is a secure configuration. Unlike CGI scripts, however, ASP requires you to run Microsoft's Internet Information Server (IIS) today. 18.7.2.1. A short ASP exampleWe can't discuss ASP in any real detail here, but here's an example of what an ASP file looks like when Python code is embedded: <HTML><BODY> <SCRIPT RunAt=Server Language=Python> # # code here is run at the server # </SCRIPT> </BODY></HTML> As before, code may be embedded inside SCRIPT tag pairs. This time, we tell ASP to run the code at the server with the RunAt option; if omitted, the code and its tags are passed through to the client and are run by Internet Explorer (if configured properly). ASP also recognizes code enclosed in <% and %> delimiters and allows a language to be specified for the entire page. This form is handier if there are multiple chunks of code in a page, as shown in Example 18-14. Example 18-14. PP3E\Internet\Other\Win\asp-py.asp

However the code is marked, ASP executes it on the server after passing in a handful of named objects that the code may use to access input, output, and server context. For instance, the automatically imported Request and Response objects give access to input and output context. The code here calls a Response.Write method to send text back to the browser on the client (much like a print statement in a simple Python CGI script), as well as Request.ServerVariables to access environment variable information. To make this script run live, you'll need to place it in the proper directory on a server machine running IIS with ASP support, after installing and registering Python. Although this is a simple example, the full power of the Python language is at your disposal when it is embedded like this. By combining Python-generated content with HTML formatting, this yields a natural way to generate pages dynamically and separate logic from display. It's similar in spirit to the more platform-neutral Zope DTML idea we saw earlier, and the PSP pages we'll meet later. 18.7.3. The COM ConnectionAt their core, both Internet Explorer and IIS are based on the COM (Component Object Model) integration systemthey implement their object APIs with standard COM interfaces and look to the rest of the world like any other COM object. From a broader perspective, Python can be used as both a scripting and an implementation language for any COM object. Although the COM mechanism used to run Python code embedded within HTML is automated and hidden, it can also be employed explicitly to make Python programs take the role of both COM clients and COM servers. COM is a general integration technology and is not strictly tied to Internet scripting, but a brief introduction here might help demystify some of the Active Scripting magic behind HTML embedding. 18.7.3.1. A brief introduction to COMCOM is a Microsoft technology for language-neutral component integration. It is sometimes marketed as ActiveX, partially derived from a system called Object Linking and Embedding (OLE), and it is the technological heart of the Active Scripting system we met earlier.[*] COM also sports a distributed extension known as DCOM that allows communicating objects to be run on remote machines. Implementing DCOM often simply involves running through Windows registry configuration steps to associate servers with machines on which they run.

Operationally, COM defines a standard way for objects implemented in arbitrary languages to talk to each other, using a published object model. For example, COM components can be written in and used by programs written in Visual Basic, Visual C++, Delphi, PowerBuilder, and Python. Because the COM indirection layer hides the differences among all the languages involved, it's possible for Visual Basic to use an object implemented in Python, and vice versa. Moreover, many software packages register COM interfaces to support end-user scripting. For instance, Microsoft Excel publishes an object model that allows any COM-aware scripting language to start Excel and programmatically access spreadsheet data. Similarly, Microsoft Word can be scripted through COM to automatically manipulate documents. COM's language neutrality means that programs written in any programming language with a COM interface, including Visual Basic and Python, can be used to automate Excel and Word processing. Of most relevance to this chapter, Active Scripting also provides COM objects that allow scripts embedded in HTML to communicate with Microsoft's Internet Explorer (on the client) and IIS (on the server). Both systems register their object models with Windows such that they can be invoked from any COM-aware language. For example, when Internet Explorer extracts and executes Python code embedded in HTML, some Python variable names are automatically preset to COM object components that give access to Internet Explorer context and tools (e.g., alert in Example 18-13). Calls to such components from Python code are automatically routed through COM back to Internet Explorer. 18.7.3.2. Python COM clientsWith the PyWin32 Python extension package installed, though, we can also write Python programs that serve as registered COM servers and clients, even if they have nothing to do with the Internet at all. For example, the Python program in Example 18-15 acts as a client to the Microsoft Word COM object. Example 18-15. PP3E\Internet\Other\Win\comclient.py

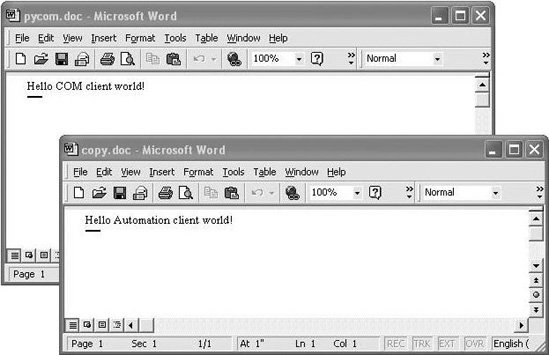

This particular script starts Microsoft Wordknown as Word.Application to scripting clientsif needed, and converses with it through COM. That is, calls in this script are automatically routed from Python to Microsoft Word and back. This code relies heavily on calls exported by Word, which are not described in this book. Armed with documentation for Word's object API, though, we could use such calls to write Python scripts that automate document updates, insert and replace text, create and print documents, and so on. For instance, Figure 18-11 shows the two Word .doc files generated when the previous script is run on Windows: both are new files, and one is a copy of the other with a text replacement applied. The interaction that occurs while the script runs is more interesting. Because Word's Visible attribute is set to 1, you can actually watch Word inserting and replacing text, saving files, and so on, in response to calls in the script. (Alas, I couldn't quite figure out how to paste a movie clip in this book.) Figure 18-11. Word files generated by Python COM client In general, Python COM client calls may be dispatched either dynamically by runtime look-ups in the Windows registry, or statically using type libraries created by a Python utility script. These dispatch modes are sometimes called late and early dispatch binding, respectively. See PyWin32 documentation for more details. Luckily, we don't need to know which scheme will be used when we write client scripts. The Dispatch call used in Example 18-15 to connect to Word is smart enough to use static binding if server type libraries exist or to use dynamic binding if they do not. To force dynamic binding and ignore any generated type libraries, replace the first line with this: from win32com.client.dynamic import Dispatch # always late binding However calls are dispatched, the Python COM interface performs all the work of locating the named server, looking up and calling the desired methods or attributes, and converting Python datatypes according to a standard type map as needed. In the context of Active Scripting, the underlying COM model works the same way, but the server is something like Internet Explorer or IIS (not Word), the set of available calls differs, and some Python variables are preassigned to COM server objects. The notions of "client" and "server" can become somewhat blurred in these scenarios, but the net result is similar. 18.7.3.3. Python COM serversPython scripts can also be deployed as COM servers and can provide methods and attributes that are accessible to any COM-aware programming language or system. This topic is too complex to cover in depth here too, but exporting a Python object to COM is mostly just a matter of providing a set of class attributes to identify the server and utilizing the proper win32com registration utility calls. Example 18-16 is a simple COM server coded in Python as a class. Example 18-16. PP3E\Internet\Other\Win\comserver.py

As usual, this Python file must be placed in a directory in Python's module search path before it can be used by a COM client. Besides the server class itself, the file includes code at the bottom to automatically register and unregister the server to COM when the file is run:

Perhaps the more interesting part of this code, though, is the special class attribute assignments at the start of the Python class. These class annotations can provide server registry settings (the _reg_ attributes), accessibility constraints (the _public_ names), and more. Such attributes are specific to the Python COM framework, and their purpose is to configure the server. For example, the _reg_class_spec_ is simply the Python module and class names separated by a period. If it is set, the resident Python interpreter uses this attribute to import the module and create an instance of the Python class it defines, when accessed by a client.[*]

Other attributes may be used to identify the server in the Windows registry. The _reg_clsid_ attribute, for instance, gives a globally unique identifier (GUID) for the server and should vary in every COM server you write. In other words, don't use the value in this script. Instead, do what I did to make this ID, and paste the result returned on your machine into your script: C:\...>python >>> import pythoncom >>> pythoncom.CreateGuid( ) IID('{1BA63CC0-7CF8-11D4-98D8-BB74DD3DDE3C}') GUIDs are generated by running a tool shipped with the Windows extensions package; simply import and call the pythoncom.CreateGuid function and insert the returned text in the script. Windows uses the ID stamped into your network card to come up with a complex ID that is likely to be unique across servers and machines. The more symbolic program ID string, _reg_progid_, can be used by clients to name servers too, but it is not as likely to be unique. The rest of the server class is simply pure-Python methods, which implement the exported behavior of the server; that is, things to be called or fetched from clients. Once this Python server is annotated, coded, and registered, it can be used in any COM-aware language. For instance, programs written in Visual Basic, C++, Delphi, and Python may access its public methods and attributes through COM; of course, other Python programs can also simply import this module, but the point of COM is to open up components for even wider reuse. 18.7.3.3.1. Using the Python server from a Python clientLet's put this Python COM server to work. The Python script in Example 18-17 tests the server in Example 18-16 in two ways: first by simply importing and calling it directly, and then by employing Python's client-side COM interfaces that were shown earlier to invoke it less directly. When going through COM, the PythonServers.MyServer symbolic program ID we gave the server (by setting the class attribute _reg_progid_) can be used to connect to this server from any languageincluding Python. Example 18-17. PP3E\Internet\Other\Win\comserver-test.py

If we've properly configured and registered the Python COM server, we can talk to it by running this Python test script. In the following, we run the server and client files from an MS-DOS console box (though they can usually be run by mouse clicks as well). The first command runs the server file by itself to register the server to COM; the second executes the test script to exercise the server both as an imported module (testViaPython) and as a server accessed through COM (testViaCom): C:\Python24>python d:\PP3E\Internet\Other\Win\comserver.py Registered: PythonServers.MyServer C:\Python24>python d:\PP3E\Internet\Other\Win\comserver-test.py Hello COM server world [1, 1] 64 1.0 Hello COM server world [2, 1] 144 1.0 Hello COM server world [3, 1] 144 1.0 C:\Python24>python d:\PP3E\Internet\Other\Win\comserver.py --unregister Unregistered: PythonServers.MyServer Notice the two numbers at the end of the Hello output lines: they reflect current values of a global variable and a server instance attribute. Global variables in the server's module retain state as long as the server module is loaded; by contrast, each COM Dispatch (and Python class) call makes a new instance of the server class, and hence new instance attributes. The third command unregisters the server in COM, as a cleanup step. Interestingly, once the server has been unregistered, it's no longer usable, at least not through COM (this output has been truncated to fit here): C:\Python24>python d:\PP3E\Internet\Other\Win\comserver-test.py Hello COM server world [1, 1] 64 1.0 Traceback (innermost last): File "comserver-test.py", line 21, in ? testViaCom( ) # COM object retains File "comserver-test.py", line 14, in testViaCom server = Dispatch('PythonServers.MyServer') # use Windows register ...more deleted... pywintypes.com_error: (-2147221005, 'Invalid class string', None, None) 18.7.3.3.2. Using the Python server from a Visual Basic clientThe comserver-test.py script just listed demonstrates how to use a Python COM server from a Python COM client. Once we've created and registered a Python COM server, though, it's available to any language that sports a COM interface. For instance, Visual Basic code can run the Python methods in Example 18-16 just as well. Example 18-18 shows the sort of code we write to access the Python server from Visual Basic. Clients coded in other languages (e.g., Delphi or Visual C++) are analogous, but syntax and instantiation calls vary. Example 18-18. PP3E\Internet\Other\Win\comserver-test.bas

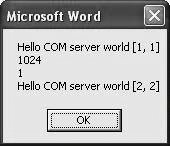

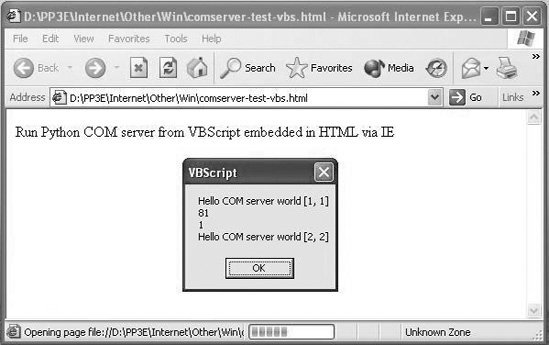

The real trick, if you're not a Windows developer, is how to run this code. Because Visual Basic is embedded in Microsoft Office products such as Word, one approach is to test this code in the context of those systems. Try this: start Word, and then press Alt and F8 together, and you'll wind up in the Word macro dialog. There, enter a new macro name, and then press Create, and you'll find yourself in a development interface where you can paste and run the VB code just shown. Running the Visual Basic code in this context produces the Word pop-up box in Figure 18-12, showing the results of Visual Basic calls to our Python COM server, initiated by Word. Global variable and instance attribute values at the end of both Hello reply messages are the same this time, because we make only one instance of the Python server class: in Visual Basic, by calling CreateObject, with the program ID of the desired server. Figure 18-12. Visual Basic client running Python COM server in Word If your client code runs but generates a COM error, make sure that the PyWin32 package has been installed, that the Python server module file is in a directory on Python's import search path, and that the server file has been run by itself to register the server with COM. If none of that helps, you're probably already beyond the scope of this text. Please see additional Windows programming resources for more details. 18.7.3.3.3. Using the Python server with client-side Active ScriptingAnother way to kick off the Visual Basic client code is to embed it in a web page and rely on Internet Explorer to strip it out and launch it for us. In fact, even though Python cannot currently be embedded in a page's HTML directly (see the note in the earlier section "Active Scripting: Client-Side Embedding"), it is OK to embed code which runs a registered Python COM component indirectly. Example 18-19, for instance, embeds similar Visual Basic code in a web page; when this file is opened by Internet Explorer, it runs our Python COM server from Example 18-16 again, producing the page and pop up in Figure 18-13. Figure 18-13. Internet Explorer running VBScript running Python COM server Example 18-19. PP3E\Internet\Other\Win\comserver-test.bas

Trace through the calls on your own to see what is happening. An incredible amount of routing is going on herefrom Internet Explorer to Visual Basic to Python and back, and a control flow spanning three systems and HTML and Python filesbut with COM, it simply works. This structure opens the door to arbitrary client-side scripting from web pages with Python. Because Python COM components invoked from web pages must be manually and explicitly registered on the client, it is secure. 18.7.3.4. The bigger COM picture: DCOMSo what does writing Python COM servers have to do with the Internet motif of this chapter? After all, Python code embedded in HTML simply plays the role of COM client to Internet Explorer or IIS systems that usually run locally. Besides showing how such systems work their magic, I've presented this topic here because COM, at least in its grander world view, is also about communicating over networks. Although we can't get into details in this text, COM's distributed extensions, DCOM, make it possible to implement Python-coded COM servers to run on machines that are arbitrarily remote from clients. Although largely transparent to clients, COM object calls like those in the preceding client scripts may imply network transfers of arguments and results. In such a configuration, COM may be used as a general client/server implementation model and an alternative to technologies such as Remote Procedure Calls (RPC). For some applications, this distributed object approach may even be a viable alternative to Python's other client- and server-side scripting tools we've studied in this part of the book. Moreover, even when not distributed, COM is an alternative to the lower-level Python/C integration techniques we'll meet later in this book. Once its learning curve is scaled, COM is a straightforward way to integrate arbitrary components and provides a standardized way to script and reuse systems. However, COM also implies a level of dispatch indirection overhead and is a Windows-only solution at this writing. Because of that, it is generally not as fast or as portable as some of the other client/server and C integration schemes discussed in this book. The relevance of such trade-offs varies per application. As you can probably surmise, there is much more to the Windows scripting story than we cover here. If you are interested in more details, O'Reilly's Python Programming on Win32 (by Mark Hammond and Andy Robinson) provides an in-depth presentation of these and other Windows development topics. Much of the effort that goes into writing scripts embedded in HTML involves using the exposed object model APIs, which are deliberately skipped in this book; see Windows documentation sources for more details.

|