I Am the CPU

|

|

The first test user comes in. Federica, our Italian moderator, gives a short introduction to the test situation and the test is under way. I, functioning as the central processing unit that operates the paper prototype, have a busy time finding correct displays and following the discussion between test user and moderator in Italian. This is something I hadn’t anticipated—I couldn’t hear the simultaneous translation from the observation room. This CPU is close to running short of MIPS.

The first adjustments to the prototype come early. A test user proposes better terms, and a missing function must be added to a menu list. Although I’m not following much of the discussion, I know that the team behind the mirror is listening to the translation and taking notes.

Testing with low-fidelity prototypes is a powerful tool in identifying interaction problems.[2],[3] Paper prototyping is a technique where user interaction takes the form of printouts of screen designs. The printouts can be rough manual drawings on notepaper or elaborate graphics rendered with designer software. A human operator acting as a computer makes paper prototypes “functional.” As each subject presses paper buttons and keys, the operator changes the user interface pictures and updates the user interface view to match.

Testing with paper prototypes provides several advantages. Speed in making simple simulations and modifications is a major benefit. In the best case it takes only minutes to create a simulation about a design idea. Applying the technique to competing design options is almost as fast. In our experience, among the other benefits of using paper prototypes are the extreme portability of the prototyping environment and, when needed, the ability to make design changes during the test sessions.

Consequently, paper prototypes provide an optimal approach for iterative design and testing. Repeating the tests not only increases the reliability of the results but also actually carries the design forward. The prototype itself evolves during the test period. Design and evaluation are not separate phases with this technique, but merge to form a user-centered design approach where idea creation, sharing, and assessment are intertwined (see Figure 8.4).

Tests can pinpoint areas for improvement in the following kinds of tasks:

“How can I navigate from start view to calendar day view?”

“Does the calendar day view provide all the needed functions?”

“Where am I now?”

With a low-fi(delity) prototype test a user is likely to respond with suggestions about essential interaction issues, and hence the designer is able to see various modification possibilities. A highly polished high-fidelity prototype, on the contrary, fosters a sense of finality that tends to inspire only proposals for minor improvements and visual niceties.[4] So lo-fi paper prototyping is not just a compromise with tight schedules after all. By adjusting the level of realism in the stimulus in user tests, one is able to influence the level of detail on which the discussion takes place.

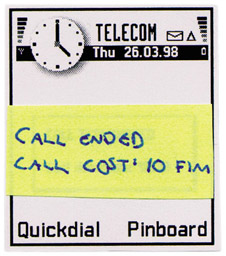

Figure 8.4: Modifications in display pictures.

Paper prototypes are the better choice for addressing major issues. The method allows instant design changes and thus immediate feedback to the user’s concerns. In our study, instant design changes initiated by users included revisions to terminology and improvements to the on-screen instructions that the phone presents. The moderator and the person who operates the prototype are busy with their tasks, but the other members of the test team are able to produce design changes during the sessions and even during a single test task. They can participate directly and support the test situation in an interactive way. For mobile handset user interface design, this possibility has been a major source of innovation and simplification of interaction sequences. Some features, however, cannot be evaluated with low-fidelity prototypes. These are, for example, detailed graphics, audio input and feedback, real-time services, timing issues and quality of service (QoS)—all critical in shaping user satisfaction in mobile communication.

The relationship between the subjects and the paper prototype varies with the individual because using the prototype requires a certain amount of imagination and flexibility from the user. As a rule, though, as experience attests,[5],[6] people tend to focus on the essential aspects of the paper prototype, namely, the tasks and interaction. As expected, the subjects in Rome were not paying attention to draft graphics and incomplete screen designs. Nor were they distracted by human error when, for example, the human CPU forgot what to do or displayed the wrong menu.

At the end of each test day the prototype was updated to reflect unexpected user actions that were encountered during the day and to implement design changes or new proposals that were too complicated to be done on the fly. Changes were carefully recorded for later validation. By the last test, the number of UI screens exceeded 100—large enough that the prototype could no longer be operated by anyone who wasn’t intimately familiar with the system. At this point organization of the material became a critical factor in the dynamic test execution.

[2]S. Isensee and J. Rudd, The Art of Rapid Prototyping. London: International Thomson Computer Press, 1996.

[3]H. Kiljander, “User Interface Prototyping Methods in Designing Mobile Handsets,” in Human-Computer Interaction INTERACT ’99, 1999, pp. 118–125.

[4]T. Winograd, “From Programming Environments to Environments for Designing,” Commun. ACM 38(6): 65–74 (1995).

[5]P. Ehn and M. Kyng, “Cardboard Computers: Mocking-it-up or Hands-on the Future,” in Design at Work, J. Greenbaum and M. Kyng, eds. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1991.

[6]S. Säde, M. Nieminen, and S. Riihiaho, “Testing Usability with 3D Paper Prototypes—Case Halton Systems,” Appl. Ergon. 29(1): 67–73 (1998).

|

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 142