Americanization versus Asianization

The American Era

In the immediate postwar years, a large number of Northern European companies—in Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Scandinavia, and the United Kingdom—felt the need to “Americanize” in order to emulate the forceful and palpably successful business techniques in production, marketing, sales, budgeting, and reporting emanating from the other side of the Atlantic. This trend toward Americanization (initially financed by the Marshall Plan) has to a great extent remained in place and has served its purpose, not only in the decades of rising production but also in periods of ubiquitous mergers, acquisitions, downsizing, and delayering.

Americanization of business was not restricted to Europe. In the Asia-Pacific zone, Australia is openly Americanized, while Japan, Korea, and the Philippines were by no means unaffected. Because the most pressing need of people in war-battered countries was to quickly raise their living standards to an acceptable level, the Americanization phenomenon was most immediately visible in the areas of industry and commerce. Almost unconsciously, however, many Europeans and some Asians, seduced by the success of the United States, permitted certain American notions and values to influence their lifestyles. Some of these were related to dress, sport, language, music, and other forms of entertainment. Other more subtle but enduring influences were in attitudes toward freedom, societal structure, the role of youth, and the reaction to government. Thus, what was ever more frequently referred to as the “Americanization” of Western Europe had, by the early 1950s, become clearly evident in such countries as Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, Ireland, and Britain—less so in countries such as Italy, Spain, Greece, and, particularly, France. In the Southern hemisphere, Australia followed the trend. Among Asian countries Japan, the Philippines, South Korea, and Thailand to some extent embraced elements of American lifestyle with some enthusiasm.

The Japanese Model

Since the mid-1980s, however, the four Asian Tigers (Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore) as well as the burgeoning economies of Thailand and Malaysia have substituted Japan for the United States and Europe as their industrial role model. Vietnam, the Philippines, Indonesia, and, most importantly, China and India are following suit. China and Vietnam may well be the next two tigers.

What does this mean for the West? The biggest markets of the next quarter of a century—China, India, and rapidly developing Southeast Asia—will be drawn toward people whose business methods—marketing, sales, negotiating, reporting, personnel policies—they understand and admire. That is to say, they will conduct business most readily with the Japanese and each other.

Western nations have demonstrated convincingly since World War II, and particularly since the recession of the 1990s, that they are ill-equipped to empathize with Asian cultural sensitivity. Cultural barriers at the national level frequently prove insurmountable, even irremovable.

At the level of corporate culture, the story is occasionally different. A handful of Western firms—ABB, Nestl, Levi Strauss, AT&T, McDonald’s, and Motorola are among them—have proven that Westerners can adapt to, attract, and sell to Asians. Any European or U.S. company wishing to capture Asian markets during the twenty-first century will probably find it advantageous to embark on an Asianization policy, just as so many European firms Americanized their business culture and approach in the 1950s and 1960s.

Asianizing

In the 1980s and early 1990s, in the wake of Japan’s economic miracle, many U.S. and some European firms embraced certain Japanese methods, especially in production and personnel policies.

For cross-cultural purposes, Asianization would seem to be a more meaningful and comprehensive concept than Japanization. An underlying common denominator of values, attitudes, and behaviors in Asia transcends Japanese methods and incorporates values and motivating forces across a vast community stretching from the Indian subcontinent in the west to Japan in the east and Indonesia in the south. China, of course, is the beating heart of this mentality.

Asianization is not overly difficult to achieve, but it has to be learned, and it demands intense focus. Without internalizing certain concepts, values, core beliefs, and communication styles, Westerners will never deal successfully with Asians. On the other hand, acquisition of a sound basis of understanding and cross- cultural competence will quickly elevate them to a position from which they can compete successfully with Asians.

Toward the end of the twentieth century, a significant shift in emphasis occurred in Western values. This is a phenomenon of great complexity that is influenced by sweeping political change, the dismantling of whole empires, the resurgence of indigenous philosophies, and dizzying technological revolution. In this heady and often euphoric atmosphere, one discerns a pervasive weakening, even discrediting, of age-old “masculine” values and a corresponding rise in the long-suppressed “feminine.”

Various cross-culturalists have discussed and written about masculine and feminine cultures. These terms need some elucidation inasmuch as they do not correspond closely to gender issues or to the ratio of men to women in different societies. The United States answers the description (by Geert Hofstede) of a masculine society, though women have equal rights in that country. Irish society, too, has many masculine traits, though women easily outnumber men. Sweden, with its taciturn males descended from Viking warriors, is classified as the most feminine culture.

What do we mean by the terms masculinity and femininity in describing the nature of a culture? My own interpretation is that masculine societies focus on power, wealth, and assets as opposed to the feminine focus on nonmaterial benefits. Similar masculine-feminine corollaries would be facts versus feelings, logic versus intuition, competition versus cooperation, growth versus development, products versus relations, boldness versus subtlety, action versus thought, results versus solutions, profits versus reputation, quick decisions versus right decisions, speed versus timeliness (doing something at the right time), improvement versus care and nurture, material progress versus social progress, individual career versus collective comfort, and personal honor versus sense of proportion.

Masculinity and the Western Intellectual Tradition

Richard Tarnas in his The Passion of the Western Mind (1991), traces in admirable detail the historical masculine bias of the Western mind.

If we examine the progression of Western philosophical, political, and economic development and practice, we see that it has been produced and canonized almost exclusively by men. Plato, Aristotle, Paul, Augustine, Luther, Copernicus, Galileo, Bacon, Descartes, Newton, Locke, Hume, Kant, Darwin, Marx, Nietzsche and Freud, to name but a few, have made significant contributions to a masculine mindset.

Tarnas emphasizes unswerving masculine dominance as follows:

The masculinity of the Western mind has been pervasive and fundamental, in both men and women, affecting every aspect of Western thought, determining…the human role in the world. All the major languages… personify the human species with words that are masculine in gender: anthropos, homo, l’homme, el hombre, l’uomo, chelovek, der Mensch, man.… [It] has always been “man” this and “man” that—“the ascent of man,” “the dignity of man,” “man’s relation to God,”…and so forth. The “man” of the Western tradition has been a questing masculine hero, a…biological and metaphysical rebel who has constantly sought freedom and progress for himself, and who has thus constantly striven to differentiate himself from and control the matrix out of which he emerged.

(It is interesting to contrast this view with that of Thai adaptation to nature, or general Asian collectivity in general).

Tarnas considers this masculine predisposition to be largely unconscious but essential to the evolution of the Western mind, which seeks to forge an autonomous, rational human self by separating it from the primordial unity with nature.

Western philosophy originated in Greece and with it began the kind of reflective, critical and analytic thinking that led to development and discovery. The tendency toward masculinity over earlier matrifocal cultures emerged four thousand years ago with the great patriarchal nomadic conquests in the Levant and in Greece.

This trend has been evidenced in the West’s patriarchal religions, from Judaism onward, in its rationalist arguments from Greece and in its objectivist science from modern Europe. The quest was for the establishment of the individual ego, the self- determining crusading individual (read man)—unique, separate, and free. (This contrasts strongly with Confucian and other Asian concepts of communitarianism and duty-consciousness). It is deceptively easy to attribute masculinity to Asian societies because of the apparently restricted role of women. In reality women are powerful behind the scenes, operating effectively in cultures that are based on feminine values such as intuition, ambiguity, trust, and cooperation.

Suppression of the Feminine

The Western drive toward rationalism and science led to the establishment of laws and religions that left little room for the feminine, the ambiguous. Laws were often principally rhetoric in the interest of (masculine) rulers. Religion has frequently been associated with deception. Protestantism in particular bases itself on masculine values—separation of right and wrong, absolutism in justice and truth, work ethic equating with success, and so on.

Both Protestants and Catholics saw rhetoric as a virtue, developed for competing in new areas of politics and commerce, highly visible today with modern lawyers, politicians and salespeople. Contrast, for example, Chinese and French behavior in meetings. The former grope for “virtue” and veracity; the latter are more interested in winning the argument than in discovering truths.

Tarnas points out that

the evolution of the Western mind has been founded on the repression of the feminine—on the repression of undifferentiated unitary consciousness, of the participation mystique with nature: a progressive denial of the anima mundi, of the soul of the world, of the community of being, of the all-pervading, of mystery and ambiguity, of imagination, emotion, instinct, body, nature, woman—of all that which the masculine has projectively identified as “other.”

The Cost

Ultimately, the pursuit of the materialistic, the scientific, the essentially rational, and the objective must produce a longing for what has been lost. Feminine values, though suppressed or ignored, have been a dormant presence all the time—important, all-embracing, and vital to human nature. The late twentieth century obsession with science, material gain, and exploitation of the planet’s resources has led to a crisis of its own making. It is a masculine crisis—a rapidly developing feeling of solitude, of alienation from family and community. This crisis is observable in the breakup of families, in the rise of crime, in various forms of pollution, in the erosion of values, in the growing disgust of public leaders in business and politics, and even in the distrust of government itself.

The Backlash

A startling reverse trend is now emerging strongly in Western culture—a shift to more feminine values. Tarnas continues:

…[It is] visible…in the…growing empowerment of women,…the rapid burgeoning of women’s scholarship, and gender-sensitive perspectives in virtually every intellectual discipline,…in the increasing sense of unity with the planet,…awareness of the ecological and the growing reaction against political and corporate policies supporting the domination and exploitation of the environment,…in the accelerating collapse of longstanding political and ideological barriers separating the world’s peoples, in the deepening recognition of the value and necessity of partnership, pluralism,…in the growing recognition of an immanent intelligence in nature,…in the increasing appreciation of indigenous and archaic cultural perspectives such as the Native American, African, and ancient European.

He concludes that a drastic shift is taking place in the contemporary psyche, a union of opposites, between “the long-dominant but now alienated masculine [strongly associated with the West] and the long-suppressed but now ascending feminine [inherently Eastern in character].”

East and West

As I consider this phenomenon from its East-West aspects, I believe a parallel fusion of Eastern and Western values and systems is also imminent. In fact much of the confusion of the modern era results from the fact that this evolutionary drama is now reaching its climactic stage. The twenty-first century is going to be different. The almost magical IT Revolution has made the East and West intensely aware of each other. Speed of communication among members of diverse cultures is eliminating barriers previously erected by government, ideologies, and cartels. How will Eastern and Western cultures affect each other, spiritually, mentally, and economically? The Asian model of society and of doing business seems destined to dominate. Weight of population, as said earlier, and the enormity of the Chinese, Indian, and Southeast Asian markets will probably be the decisive factors.

The rise of the feminine in the West coincides with the necessity to accept Asian values. Let’s see what Eastern values and feminine values emerging in the West have in common:

- Communitarianism and cooperation

- Leadership by the strong but protection of the weak

- Intuition, mysticism, and instinct seen as factors to be reckoned with

- The influence of the family

- The importance of educating children

- Thrift, frugality, prudent saving

- Networking

- Patience, endurance, persistence

- Balanced perspectives and a sense of proportion

- Ascendance of morality over materialism

Cross-culturalists such as Samuel Huntington focus on Asian strength, declaring that the West must abandon its universalist aspirations. China, Japan, the East in general, Muslims, and Africans are poor candidates for anything more than surface Westernization. The “Davos Culture” annually brings together one thousand businesspeople, bankers, government officials, intellectuals, and journalists in the prestigious Swiss resort. Those assembled control virtually all the world’s international institutions and the bulk of its economic and military capabilities. The group’s formula for progress is individualism, market economics, political democracy, the application of technology, and rapid globalization—a combination that would appear irresistible. Yet outside the West, less than 1 percent of the world’s peoples share this culture. Huntington looks at the growing hegemony of China, reflects that culture follows power, and forecasts that Japan, Southeast Asia, and possibly India will drift away from the West and enter into conflictual relations with the United States, in particular.

Other culturalists, such as William Rees-Mogg, hold a different view. They hypothesize that Japan may grow increasingly alarmed at the prospect of Chinese dominance in Asia and may, along with India and most of Africa, exhibit continued dependence on the ability of the United States and Western Europe to counterbalance China. Rees-Mogg does not believe that Asia would coalesce in hostility to Western culture while it is still in the process of establishing its own balance of power with China. He sees the emergence of a new layer of culture, neither Western nor Eastern but rather both, where consumerism, education, travel, fitness, spirituality, fashion, trends, and the Internet combine in what he calls “a yearning for ecstatic experience”—not the West versus the East, but the new versus the old. His conclusion is that the next age in Asia will belong more to Bill Gates than to Confucius.

Given the durability of Confucianism, I rather doubt this, but the fusion of technology, art, and traditions; of Eastern and Western strengths; of masculine and feminine values seems ultimately inevitable and desirable in the twenty-first century. When Prime Minister Datuk Seri Mahathir Mohamad of Malaysia told the assembled heads of European governments in 1996, “European values are European values—Asian values are universal values,” he hardly addressed an enthusiastic audience. What were the grounds for such a sweeping judgment? No doubt he had in mind that while the current Western civilization is usually considered as having emerged about A.D. 700, Chinese civilization is five thousand years old, Indian, nearly four thousand. It may well be that the West since the advent of Christianity, the Renaissance, Magna Carta, and the Industrial and IT Revolutions believes it has mended the world, but three billion people east of Suez have another version. Huntington advises us “to preserve and renew the unique qualities of our Western civilization.” This is surely a worthy goal. If we can also embrace a degree of Asianization, just as we grabbed Americanization in 1945–1946, we will pave the road to better spiritual understanding, intercultural harmony, and better business.

In order to go about this, we must take a closer look at Asian political and management systems and how they are affected by Asian values, communication styles, and organizational patterns; then we must write ourselves a manual for adopting and benefiting from Asian ways and methods.

|

Western |

Asian |

|---|---|

|

Democracy |

Hierarchy |

|

Equality |

Inequality |

|

Self-determination |

Fatalism |

|

Individualism |

Collectivism |

|

Human rights |

Acceptance of status |

|

Equality for women |

Male dominance |

|

Social mobility |

Established social classes |

|

Status through achievement |

Status by birth, through wealth |

|

Facts and figures |

Relationships |

|

Social justice |

Power structures |

|

New solutions |

Good precedents |

|

Vigor |

Wisdom |

|

Linear time |

Cyclic time |

|

Result orientation |

Harmony orientation |

|

Differing values are at the heart of intercultural friction and will not change quickly under any circumstances. The Westerner has no alternative but to accept them. He or she may, however, begin to gain insight into the positive features of, for example, relationship building, harmony, and the following of good precedents. Is there such a thing as real equality? Is there not an element of fatalism in Western religions? |

|

|

Western |

Asian |

|---|---|

|

Direct |

Indirect |

|

Blunt |

Diplomatic |

|

Polite |

Very courteous |

|

Talkative |

Reserved |

|

Extrovert |

Introvert |

|

Persuasive |

Recommending |

|

Medium-strong eye contact |

Weak eye contact |

|

Linear-active |

Reactive |

|

Unambiguous |

Ambiguous |

|

Decisive |

Cautious |

|

Problem solving |

Acceptance of the situation |

|

Interrupts |

Does not interrupt |

|

Half listens |

Listens carefully |

|

Quick to deal |

Courtship dance |

|

Concentrates on problems |

Concentrates on agreed items |

|

If different values are the root of conflict, it is usually the inadequate communication of them that leads to misunderstanding. In this area mutual progress is often achievable. It is much easier, through training, to acquire communication skills than it is to swallow alien core beliefs embedded in another’s psyche. Increasing international contact and technology will play an important role in improving cross-cultural communication. |

|

|

Western |

Asian |

|---|---|

|

Individual as unit |

Company, society as unit |

|

Promotion by achievement |

Promotion by age |

|

Horizontal or matrix structures |

Vertical structures |

|

Profit orientation |

Market share priority |

|

Contracts as binding |

Contracts as renegotiable |

|

Decisions by competent individuals |

Decisions by consensus |

|

Specialization |

Job rotation |

|

Professional mobility |

Fixed loyalty |

|

Western companies embracing a degree of Asianization will hardly abandon their own organizational structures. What is required is an appreciation of the nature of Asian frameworks. Asian variations from their own patterns may appear positive or negative, but a better orientation toward them will be advantageous. Is there anything inherently horrid about renegotiating a signed contract? Decisions made by consensus are usually slow, but they are often sound. |

|

The Asian Model

It is only natural that the West cherishes its own institutions; yet many of them—the electoral system, social justice, equality for women, individual rights, limited government, equality of opportunity, the sacred nature of property rights, social and professional mobility—are relatively recent inventions, with little currency in the West before the late nineteenth century. Slavery was abolished (with some difficulty) in the United States in 1865; women could not vote in Britain until 1928 and in Switzerland, not until 1971! Double standards in repelling aggression, promoting democratic movements, and preaching for nonproliferation are still evident in Western practice.

Criticism of Western universalism (seen by others as imperialism) from Asian and other sources has led scholars and businesspeople in the West to pay closer attention to the Asian way of doing things, and they see many attractive features. These include a genuine work ethic (encouraged by Confucius), a collective entrepreneurial spirit, an emphasis on education, high savings rates, positive government involvement in export expansion, dynamic community spirit, unanimous directional effort inside companies, loyalty to firms, a comforting focus on people, a high duty-consciousness, professional obedience among employees, basic trust as opposed to mere observance of legalities, and—in the case of Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore—vigorous rein- vestment of profits in research and development and improvement of resources and infrastructure.

Asians, for their part, have adopted certain Western features as they have modernized. Examples are Sony’s development of a marketing strategy that was highly successful in Europe and the United States and Samsung’s graft of Western techniques onto its authoritarian corporate structure.

The Asian Mind

The common (and beneficial) features of the Asian business model, noted by the West, derive from an Asian mentality that merits close scrutiny by those who wish to trade with Asians or, indeed, enter into ever closer commercial relationships. When we talk of the “Asian mind,” we call up visions of behavior typical of Far Eastern countries such as China, Japan, and Korea— confident adherents of Confucianism—but as mentioned earlier, there is an underlying common denominator of comportment in Asia, incorporating the values and traditions respected by a vast community from Japan in the east to the Indian subcontinent in the west. In this respect the Asian mind is a reality, even though it spans an awesome expanse of territory and a plethora of diverse religions and creeds. The basic Asian values and rules regarding courtesy and respect, humility, filial piety, hierarchical society, emphasis on formality and ritual, sense of collective duty and welfare, faith in education, closeness of family, and loyalty to friends are as real and imperative in Bombay and Djakarta as they are in Tokyo and Beijing.

Government Control

Asians believe, in line with Confucianism, that business is a low form of activity and therefore must be subject to government control. This has political overtones in China, Vietnam, and North Korea, but it is visible in more voluntary form in Japan (“Japan Inc.”); in South Korea, where massive government funding enabled the chaebol to compete with the Japanese keiretsu; and in Taiwan, Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore, where government leaders were conspicuous in promoting the national economy.

This general attitude toward the role of business and the involvement of public figures is often puzzling to Western businesspeople. In Asia business must be seen “to help the country.” Profit is of course necessary, but it is secondary. There is a “correct way of doing things,” and Asian rulers, believing in their innate superiority, tend to be autocratic, “as they know best.” Power, however, is derived ultimately from sincerity and competence; therefore, “bad rulers” may be overthrown. Opposition parties may be disloyal. Asian students are entitled to revolt if abused. This happened regularly in South Korea, occurred once or twice (with tragic results) in China, and is becoming a reality in Indonesia.

The downside of the Confucius-inspired government interference with business is that bureaucracy has too much power and also has exaggerated respect for authority figures. The emphasis on harmony (hopefully unanimity) leads to legal action being viewed badly. (This has often cramped the style of American firms who feel hard done by in Japan and Korea.) The reality is that in most cases it is better not to sue but to improve one’s relations with government officials (who occupy an honored position in the Confucian scheme of things) instead.

Asian Logic

Although I discussed logic and culture in chapter 7, here the focus is on Asian logic, which differs so markedly from Western thinking that it often simply appears illogical. Things that seem obvious, or cut-and-dried, in Europe or the United States are not at all evident to Asians. Westerners often refer to black and white, right and wrong, good and evil. These are threatening concepts to most Asians, who are completely at ease with the ambiguity of seemingly incongruous components functioning in harmonious coexistence. One can present two contradictory hypotheses to an Indian, for example, and he or she will courteously endorse both of them, beaming all the while. Truth itself is ephemeral, being regarded as a dangerous concept in Japan and subjected to “virtue” in China.

Only four cultural groups use “scientific” truth as a tool for discussion and conducting meetings. These groups are (1) Nordics, (2) North Americans, (3) Germanics (Germans, Austrians, Swiss Germans), and (4) Australians. These groups believe that facts and figures constitute a sound foundation for reaching decisions and conclusions. Other cultures have more subtle interpretations of truth, usually connected with an unwillingness to confront or a desire to protect face. Asians, Arabs, Africans, South Americans, and many Europeans will indulge in a certain amount of “window dressing” when describing a situation. In Italy and Greece, truth is negotiable, in England it is sometimes seen as offensive (unless coded), in Polynesia it may be considered too outspoken for comfort, and in Russia, outright perilous. Asians do not see an unbreakable bond between truth and logic.

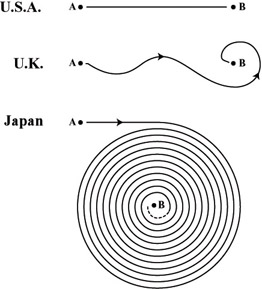

When constructing arguments, Asians do not normally follow Western linear logic. Instead their thought moves toward an objective in a sort of spiral. The Westerner is confused by frequent non sequiturs. The Westerner uses argument and counterarguments, evidence, facts, and explanation, tackling problems and seeking solutions. Asians avoid taking sides, counterargument, any kind of confrontation. They seek agreement not by proving a point but by “zoning in,” in ever decreasing circles, on what appears to be a mutually congenial state of affairs. Argument itself, in Asian eyes, is seen as a scattered number of points that, through discussion, gradually converge and eventually unify.

Getting to the Point

As if this is not difficult enough for the Westerner to comprehend, Asian Zen concepts about the changing nature of things complicate matters somewhat further. What is said today may be rather different tomorrow. What was done yesterday may be seen in a different light today. The Chinese, particularly, see change as a constant. It is hard for the Westerner to swallow that the only constant is change itself, but this old Asian belief has been fast gaining currency elsewhere at the beginning of the twenty-first century. “Managing change” is a popular seminar topic in the United States and Europe. Asians have long believed that one’s actions must be changed on a daily basis to achieve the best results. Every business relationship is in constant transition; therefore, one must continually pay attention to all aspects of business. Japanese, Chinese and Koreans—basically reliable in their arrangements—often cancel meetings or appointments at a few hours’ notice, to the great chagrin of Westerners. The reason usually given is, “Circumstances have changed.”

Attitudes toward the West

Most Asian countries are very nationalistic, with a strong ethno- centric mentality. Western excesses during colonial times resulted in lingering xenophobia, particularly against former colonial masters. Indians direct their criticism mainly against the British, the Indonesians against the Dutch, and so on. Rancor is, however, not so biting as to inhibit trade relations. Indians are still courteous to British visitors, Indonesians use Dutch technicians and engineers, and Filipinos share many ideals with Americans. Countries that were never colonized are selective in their xenophobia. Americans are very popular in Thailand, and the English enjoy their reputation as “gentlemen” in Japan.

In all cases red-carpet treatment is accorded by Asians to business partners, including generous hospitality, respect, protection of face for all parties, gift giving, and so on. Asians attach tremendous importance to form, symbolism, and gesture. Of course they expect all their courtesies to be reciprocated, but they are unlikely to fail in these respects when receiving foreign visitors.

These gestures should not, however, be mistaken for genuine warmth of relationship. Asians are quite prepared to build relationships, but there remains a lot of work to be done!

Variations in Mindset

While Westerners often find Asians opaque, distant, closed, impassive, “inscrutable,” and strange in other ways, one should bear in mind that Asians, for their part, are often equally bemused by Western “idiosyncrasies.” Some Western peculiarities are a source of unease to most Asians, who tend to be literal-minded and can, therefore, easily misinterpret Western humor. When an American opens a seminar or a presentation with a joke or a wisecrack, Asians may think it is an integral part of the presentation. They sometimes think that Americans (and some other Anglo-Saxons) commercialize, trivialize, or “humorize” matters that for them are human events of great import.

Most Asians believe that the West suffers from a certain relative decadence, an abandonment of moral standards that are both visible and deeply held in modern Asian life—respect for parents, frugality, thrift, saving, politeness, collective spirit, and so on. They perceive a lack of solidarity and a fragile loyalty in many Western firms and among consumers (particularly in the United States, where employees frequently switch to the competition and shop- pers abandon brands and stores without a second thought). Criticism of such declining morals is rarely so overt as that expressed by many Islamic cultures, but it is often an undercurrent in Asians’ cautious dealings with Westerners. Asians grope for trust and respect; they respond warmly in due course when these are confirmed. Westerners are aware of and sometimes obsessed with their “quality of life” and are increasingly in search of it. This expression still has little meaning in Confucian Asia, where working hard is preferred and Westerners are seen as somewhat slothful. The Japanese pay ready tribute to the German work ethic but fail to understand how Germans can take a six-week vacation (and enjoy it!). Asians feel a certain amount of guilt about taking holidays and often curtail these in the company’s interest. With increasing mutual awareness of each other’s lifestyles, one can hope that traits now considered idiosyncratic will be recognized as interesting human variations not necessarily leading to conflict.

Negotiating

Fundamental variations in Western and Asian mindsets are readily observable in the different approaches to negotiating. The most important thing for a Westerner to remember when negotiating with Asians is that the real negotiations rarely take place in the context of a formal meeting. Americans and Europeans hold meetings to negotiate terms, make decisions, and initiate action. In most Asian countries the primary aim of a meeting of the partners is to gather information and to compare the positions of the two sides. There will be little attempt to persuade the partner to change his or her position. In Japan, particularly, one does not air differences of opinion in public. The correct procedure is to clarify positions, note the differences, show respect for the other side, and then escape for internal discussion. Once the gap between the respective positions has been properly analyzed, a new stance can be taken up that, through skilful modification, will be more acceptable to the partner. Asians assume that the other side will be taking similar steps to narrow the differences of opinion. Before the next formal meeting, informal contacts are usually made between the two parties, often at a lower level and probably in a social context. The numerous bars and clubs of Tokyo, Hong Kong, Taipei, Seoul, and Singapore witness many such encounters each evening. Younger middle managers are often involved, sounding out their counterparts and discussing possible strategies for furthering the business. They are in fact negotiating in an informal but effective manner. In such a situation concessions may be discussed without loss of face and without directly involving senior figures. Westerners should take full advantage of such discussions, whether at elaborate Chinese banquets, cocktails at the Imperial Hotel, or lunch at the Oriental in Bangkok.

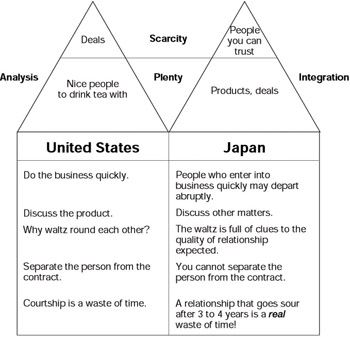

When senior people on the Asian side feel that positions are closer, further “negotiation meetings” may be held. The purpose of these meetings is to confirm or ratify progress that has been made in the interim and to create further harmony between the parties at all levels. Concessions that have been made will be pleasantly referred to; sticking points may be mentioned in an indirect way without exaggerating their importance; confrontation will still be avoided. There is plenty of time for differences to be sorted out—Asians have great patience. Westerners, and particularly Americans, who have much less patience, will make a mistake if they press for quick concessions. Asians will not be rushed. In Hong Kong, Singapore, and Seoul the pace is often faster, but only when it suits the Asian counterparts. In the PRC, Japan, Vietnam, Thailand, and Southeast Asia the tempo is much slower than Americans and Northern Europeans are accustomed to. Asians, who are looking for long-term agreements and solutions, prefer discussions to be protracted. Basically, they are trying to decide if you are really the type of company (or person) they want as a long-term partner. The diagram on the next page indicates American impatience to discuss and get on with the deal, as opposed to the Asian preference to defer real business discussion until the parties involved have socialized sufficiently to feel confident that the partnership will be successful.

Asians’ courtesy and amiability during negotiations should not, however, blind the Westerner to their aims and intent. For Asians, the objective of competitive business is total victory. This makes them highly pragmatic. They do not have the same sense of business ethics as Anglo-Saxons and Northern Europeans do. They believe in “situational ethics” leading to pragmatism, usually in their favor. With partners, they are not overly concerned with division of profit but rather seek business advantage such as joint venture control or significant market share. When actually negotiating, they apply pressure gently but persistently and continue to do so until they are firmly stopped. It is a mistake to make concessions without asking for something in return. They easily misinterpret generosity for weakness. When they apply pressure, it is advisable to “revolt” early on—in an amicable way, of course.

The Courtship Dance

When an agreement is finally concluded and a contract signed, the Westerner must understand that the document is a statement of intent and not fully binding in the Western sense. Asians honor their word—more than most of us—but as change is viewed as inevitable and constant, they have no compunction about seeking modification of terms if market conditions alter. This is especially difficult for Americans and Germans, who attach great importance to the written word. Latins are less perturbed, as “renegotiation” is not unknown in their world. Chinese, Japanese, and other Asians rarely have difficulty in renegotiating with each other, as force majeure is in plentiful supply in Asia, where it sits well with the continental fatalism.

Decision Making

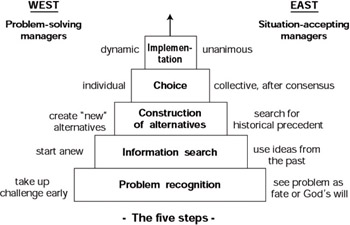

The Asian tendency toward fatalism is evident in their decision making. Much has been written about the famous Japanese ringisho system, where ideas are bandied back and forth between workers and middle managers before ascending (after considerable time has passed) to the senior echelons, where ratification will take place. Suffice it to say that decisions in Asia take longer than they do in the West. Another basic cultural difference is the manner in which decisions are made. The diagram on the next page indicates how Western managers are essentially problem solvers, whereas Asian managers often accept situations as fate or God’s will and make the best of them. This does not mean that they allow a negative state of affairs to continue, but instead of starting from scratch, they look back to see what their company (or another one) did in similar circumstances. Life and experience are long, and there must be many good precedents. There is little new under the sun. Managers who are willing to base their business policies on the strategic thinking of Sun Tzu in his book The Art of War (published in the fourth century B.C.) are quite happy to search for historical precedents to show them the way forward.

Decision Making

If the Westerner considers this manner of decision making lacking in spontaneity and originality, the Asian replies, “So what?” In Confucian Asia as well as in India skillful imitation is prized more than originality. This is obvious in the repetitive sequence of Asian art, where masterpieces are faithfully imitated by succeeding generations. Just as painters do not believe they can surpass their old masters, so modern Asian managers are reluctant to think, in all humility, that they can make new, epoch-making decisions in business. Indians are exceptions inasmuch as they are risk takers, but even they see failure as God’s will, or karma.

Asian Concept of Leadership

Westerners used to dealing with managers who have risen to the top via meritocratic achievement need to reorient themselves when encountering leaders or top managers in Asian countries. There are, of course, a large number of professional managers in Japan, Korea, and India who have great competence and qualifications, but even they stand on rungs in a rigid social ladder spelled out by Confucius many centuries ago. The Chinese philosopher was especially concerned with the concept of an organized, hierarchical society led by wise men. Most Asians at the beginning of the twenty-first century are still governed by Confucian discipline, as indicated in the following maxims:

- Society is based on unequal relationships.

- It is organized in a strict hierarchy with a strong leader or leadership group at the top.

- In theory leadership is made up of wise men (even scholars) who possess vision and are eminently capable of leading.

- Orders from a superior are to be obeyed without question.

- Strong obligations exist both top-down and bottom up in the hierarchy.

- Subordinates owe allegiance; superiors owe guidance and protection.

- In theory if leaders abuse their power (fail to protect), they may be overthrown.

- It is up to intellectuals (possibly students) to expose such abuse and to act to remove abusers.

- Except in communist regimes, leadership is gained through birthright (traditional upper-class families, wealth, etc.).

- Such leaders are expected to rise to the aspirations and expectations of those to be led.

- Subordinates are generally satisfied with their place in the societal and business hierarchies.

- Suggestions for promotion are expected to come from above.

- Promotion is granted more in reward for loyalty and seniority than for merit or brilliance.

- The leader is seen as the father of a big family, where everyone thinks collectively.

- The leader should place the welfare of employees before or on a par with the creation of profit.

- Asian leaders are situation-accepting managers rather than decision makers.

- When making decisions, leaders look for precedents in the past.

- Most decisions are made through consensus.

- Leaders should achieve unanimity through soft persuasion.

- Though leaders must display paternalism, power distance remains great.

Confucianism

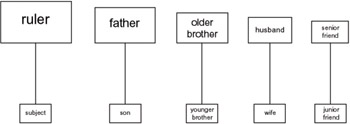

Confucius taught that stability in society is best achieved through a hierarchy based on unequal relationships between people. He itemized five basic relationships, each with very clear duties.

A ruler or leader (today this might mean top manager or CEO) commands absolute loyalty and obedience from his people (employees). He must, however, strive to better their lot. A husband rules over his wife in a similar manner. She must bear him sons. Children must be loyal to their parents, who will educate them.

Confucianism's Five Relationships

Children must look after their parents in their old age. Older brothers advise their younger brothers, who must accept their advice. The same applies to older and younger friends. Such unequal relations do not sit well with people raised in Western democratic societies. French and German managers often conduct business in an autocratic manner—and expect discipline—but such expectations serve pragmatic ends rather than theoretical ones. The Confucian husband-and-wife relationship might work in Sicily or some South American cultures, but it has changed radically in the Anglo-Saxon world and Northern Europe. Filial piety survives in Latin cultures, especially in Italy and Hispanic countries, but the seniority of older brothers and older friends carries little weight in many other parts of the West. It is, however, a present-day reality in Asia, where advice from older siblings and friends is generally followed. Japanese managers often compare the date of their university degrees to decide superiority.

Other features of Confucianism are humility, courtesy, and enduring loyalty between friends. While all these things are quite acceptable in the West, their very intensity in Asia can sometimes be overwhelming. Westerners have difficulty adjusting to Asian levels of courtesy and often feel “upstaged” by the host’s attention to details of the guest’s comfort as well as by lavish entertaining and gift giving.

Face

In Confucian societies and in other parts of Asia, “face” dominates everyday behavior. Some Europeans hate to lose face more than others (it is a serious matter in Spain, southern Italy, and, to some extent, Finland), but in general the Anglo-Saxon and Northern European commitment to compromise and flexibility of opinion make loss of face a fairly acceptable matter—a gentle climb- down or admission of mistakes made. One can be persuaded to negate one’s previous affirmation without having one’s integrity questioned. This is not the case in modern Asia, where it is unacceptable to criticize another’s statement in public or to expose an error in front of others. Mistakes may be noticed and should be corrected by indirect means in due course, but in public one simply nods in agreement and holds one’s tongue. This may seem hypocritical to many Westerners, especially outspoken Americans, Dutch, and Australians, but saving face is not far removed from Italian diplomatic bearing or indeed the British reluctance to “rock the boat.”

Whatever the Westerners’ opinion, however, they must protect Asian face at all times. Not to do so would shame the critic more than the person criticized. The damage would also be difficult (or impossible) to repair. It would probably mean the end of a business relationship not only with the victim but also with all who witnessed the incident. Even if the hapless foreigner causes someone to lose face unintentionally, the situation may be irretrievable. When one does so inadvertently, it is best to immediately withdraw the remark (with some good excuse) and to praise the victim as quickly as possible. One constantly has to bear in mind the status of all present and to accord them the respect that their rank or status commands. This involves treating people differently and occasionally being (in Western eyes) somewhat obsequious to “superiors.” At the same time, one must show courtesy to “inferiors.” The ability to imitate Asians in their protection of face can be the Westerner’s key to success in business or social relations all the way from India and Pakistan to Japan. If one bears in mind that every decision or action of one’s Asian partners is taken against a background of protecting face (yours and theirs), one is led to a better understanding of behavior that might appear enigmatic or lacking adherence to Western logic.

The notion of face is not going to change in the twenty-first century—at least not in Asia. Thousands of years old, it is embedded in every Asian culture. It is in itself a defensive weapon against greater force, gaining momentum in adverse circumstances. Westerners mostly understand the concept. What they must adjust to is the difference in degree.

Summary

Where We ve Come From

- After 1945 many European nations (and some others) accepted a strong dose of Americanization, imitating U.S. business techniques in production, accounting, marketing, and sales. It did not kill them (or their cultures), and the material benefits outweighed the disadvantages.

- The negative effects of Americanization were experienced in the gradual erosion or dilution of (European) values, as impressionable youth embraced many aspects of American lifestyle.

- American business and management techniques lost ground in the 1970s and 1980s, as the Asian Tigers adopted the successful Japanese business model.

- In the 1990s the West frequently demonstrated that it was ill equipped to deal with Asian cultural sensitivity.

Whither the Future?

- Westerners need to establish a successful modus operandi for the new century if they are intent on globalizing their business and exports.

- Linear-active (Western) societies have everything to gain by developing empathy with reactive and multi-active ones.

- Technology has now made East and West intensely aware of each other; some synthesis of progress and cooperative coexistence will eventually emerge. The size of Asian populations and markets suggests their eventual dominance.

- Just as there were benefits to be obtained from Americanization in 1945, there are advantages to be gained from an Asianization policy in the twenty-first century. Both Europeans and Americans would do well to consider this.

- Acceptance of a certain degree of Asianization now would facilitate better understanding of Asian mentalities and perhaps preempt future Chinese hegemony in the commercial and political spheres.

- The West should study Asian values as well as patterns of communication and organization and learn from these. There are visible benefits in Asian systems.

- The West should also study the “Asian mind” and how it perceives concepts such as leadership, status, decision making, negotiating, face, views of morality, Confucian tenets, and so forth.

- Fortunately, the rise of feminine values in the West at cross- century smooths the way for Asianization, as many of these values coincide with Asian values.

Just as the Americanization (of Europe) progressed from influencing business practice to permeating the social scene, a similar phenomenon will occur with Asianization. That is to say, Westerners will be influenced by and adopt aspects of Asian lifestyles that will have a lasting effect on social behavior, aims and aspirations, sense of morality, concept of duty, and attitudes toward politics and government.

The implications of such a shift in Western thinking and comportment are mind-boggling, if not cataclysmic. Societies such as the French, American, Swedish, and possibly the British and German are successful in their own right and may be less inclined to modify their culture in an Asian direction than are less powerful nations. The Americans currently find little wrong with their economic model, nor do the French with their cultural one. Nevertheless a degree of feminization has already taken place in most Western countries, and the growing distaste of the younger generations for the hard-nosed exploitation of people and natural resources will make Asianization an attractive policy. After all, business is business, and there are billions of customers out there.

Preface

- From 2,000,000 B.C. to A.D.2000: The Roots and Routes of Culture

- Culture and Climate

- Culture and Religion

- Cross-Century Worldviews

- Cultural Spectacles

- Cultural Black Holes

- Cognitive Processes

- The Pacific Rim: The Fourth Cultural Ecology

- The China Phenomenon

- Americanization versus Asianization

- Culture and Globalization

- Empires Past, Present, and Future

Conclusion

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 108