Keys to Effective Decision Making

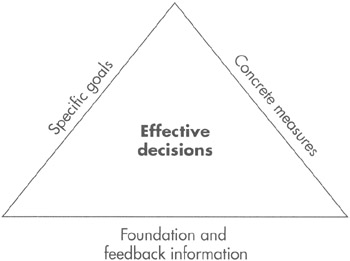

In the previous section, we learned that three keys are necessary for effective decision making: specific goals, concrete measures, and timely foundation and feedback information, as shown in Figure 1-1. In this section, we take a detailed look at each of these three keys to learn how to encourage effective decision making.

Figure 1-1: Three keys to effective decision making

Are We Going Hither or Yon?

In Mel Brooks's film, The Producers, Max and Leopold set out to stage an absolutely horrible Broadway musical, certain to fail, so they can abscond with the investor's money. Aside from this entertaining exception, organizations do not set out to fail. On the contrary, they come together, raise capital, create organizational charts, draw up business plans, prepare massive presentations, and have endless meetings, all to succeed. The first, largest, and ultimately fatal problem for many of these organizations is they do not define exactly what that success looks like. They don't know what the destination is.

An organization may have some nebulous goals in its mission statement. Phrases such as "superior customer satisfaction," "increased profit margin," or "better meeting our community's needs" grace the reception area, the annual report, and the entryway to the shareholder's meeting. These are great slogans for building a marketing campaign or generating esprit de corps among the employees. They do not, however, make good milestones for measuring business performance.

"Superior customer satisfaction" is a wonderful goal. (The world would be a much happier place if even half the companies that profess to strive toward superior customer satisfaction would actually make some progress in that direction.) The issue is how to measure "customer satisfaction." How do we know when we have reached this goal or if we are even making progress in that direction? What is required is something a bit more concrete and a lot more measurable.

Rather than the ill-defined "superior customer satisfaction," a better goal might be "to maintain superior customer satisfaction as measured by repeat customer orders with a goal of 80% repeat orders." This goal may need a few more details filled in, but it is the beginning of a goal that is specific and measurable. We can measure whether our decisions are taking us in the right direction based on the increase or decrease in repeat orders.

"Increased profit margin" makes the shareholders happy. Still, the organization must decide what operating costs impact profit margin and how they are divvied up among a number of concurrent projects. We may also want to state how large the increase to profit margin must be in order to satisfy the investors. Does a 1% increase put a smile on the shareholders' faces or does our target need to be more in the 5% range? Once these details are added, we have a very specific target to work toward.

"Better meeting our community's needs" is a noble goal, but what are those needs and how can we tell when they are met? Instead, we need to select a specific community need, such as increasing the number of quality, affordable housing units. We can then define what is meant by quality, affordable housing and just what size increase we are looking to achieve.

To function as part of effective decision making, a goal must

-

Contain a specific target

-

Provide a means to measure whether we are progressing toward that target.

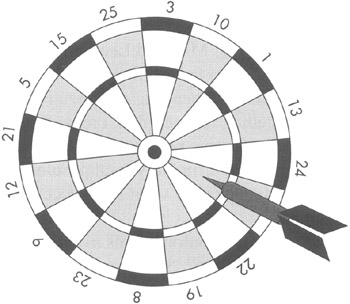

As with the dart board in Figure 1-2, we need both a bull's-eye to aim for and a method for scoring how close we came to that target.

Figure 1-2: Required elements of a goal to be used in effective decision making

Is Your Map Upside-Down?

Goals are important. In fact, they are essential to effective decision making, as discussed in the previous section. However, goals are useless without some sort of movement toward reaching that goal. The finish line can only be reached if the ladies and gentlemen start their engines and begin the race.

This is where decision making comes into play. Each decision moves the company in a particular direction. Some decisions produce a giant leap. These are the policy and priority decisions usually made in the upper levels of management. These decisions determine the general course the organization is going to take over a lengthy period of time, a fiscal year, a school calendar period, or perhaps even the entire lifetime of the organization. It is essential that these decisions point the organization toward its goals, if those goals are ever going to be reached.

Some decisions cause the organization to make smaller movements one way or another. These decisions range from workgroup policies to daily operating decisions. It could even come down to the way a particular employee decides to handle a specific customer complaint or which phone number a sales representative decides to dial next. These small variations in the organization's direction, these small steps forward or backward, when added together become a large determinant of whether the organization ultimately reaches its goals. For this reason, effective decision making is needed at all levels of the organization.

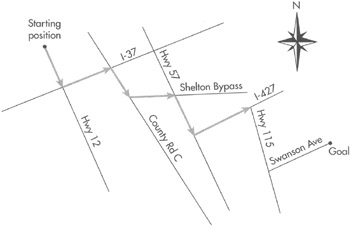

But how do we know when a decision moves the organization, either by a leap or a baby step, toward the goal? We need a method of navigation. As in Figure 1-3, we need a map or, these days, perhaps a GPS device, to tell us where we are relative to our goal and show us if we are moving in the right direction.

Figure 1-3: Measuring progress toward the goal

This is the reason goals must include a means of measuring progress. By repeatedly checking these measures, we can determine whether the organization is making effective decisions. When the measures show we are heading away from the goals, the decision making can be adjusted accordingly. As long as our measures are correctly defined to match our goals, we have a good chance of moving ever closer to those goals.

Panicked Gossip, The Crow's Nest, Or the Wireless

The sinking of the Titanic provides a catastrophic illustration of poor decision making. The ship was traveling at high speed in ice-laden waters—an unfortunate decision. This tragedy also provides us with an illustration of how important it is to receive feedback information in a timely manner.

News that there were "icebergs about" reached different people aboard the ship at different times. Most passengers found out about the fatal iceberg through panicked gossip as they were boarding the lifeboats. Of course, the passengers were not in a position to take direct action to correct the situation and, by the time they found out, it was far too late.

The ship's captain got news of the iceberg from the lookout in the crow's nest of the Titanic. This warning was received before the collision and the captain attempted to correct the situation. However, the Titanic could neither stop nor turn on a dime so, ultimately, this warning turned out to be too late.

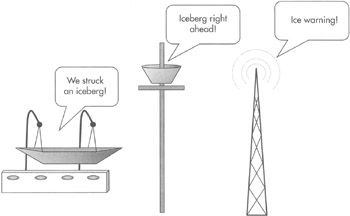

Another warning had been received earlier on board the Titanic. The wireless operator received an ice warning from another ship, the America, and even passed that warning on to a land-based wireless station. This message was received hours ahead of the collision; plenty of time to take precautions and avoid the tragedy. Because of the large workload on the wireless operator, this warning was never relayed to anyone on the Titanic with the authority to take those precautions. The feedback information aboard the Titanic is shown in Figure 1-4.

Figure 1-4: Aboard the Titanic, feedback information was not given to the decision makers in a timely manner.

In the previous section, we learned about the need to use defined measures to get information to our decision makers. As the story of the Titanic illustrates, the timing of this feedback information is as important as its content. Feedback information that does not reach the proper decision makers in a timely manner is useful only to those investigating the tragedy after it has occurred. The goal of effective decision making is to avoid the tragedy in the first place!

As with the passengers on the Titanic, information in our organizations may come in the form of panicked gossip among lower-level personnel. Unlike those passengers, these people might even pick up some important information in advance of a calamity. Even if this is the case, these people are not in a position to correct the problem. Furthermore, we need to base our decision making on solid information from well-designed measures, not gossip and rumors.

Like the captain of the Titanic, the decision makers in our organizations often get feedback information when it is too late to act. The information may be extremely accurate, but if it does not get to the decision makers in time to make corrections, it is not very helpful. The numbers in the year-end report are not helpful for making decisions during the current year.

Similar to the wireless operator, our organizations often have a person who has the appropriate information at the appropriate time. The situation breaks down when this person does not pass the information along to the appropriate decision maker. This may occur, as in the case of the Titanic's wireless operator, because that person is overworked and has too much information to get out to too many people. It may also occur because organizational policies or structures prevent the flow of information. Finally, this may occur because the infrastructure is not in place to facilitate this communication.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 112

- ERP Systems Impact on Organizations

- The Second Wave ERP Market: An Australian Viewpoint

- Context Management of ERP Processes in Virtual Communities

- Relevance and Micro-Relevance for the Professional as Determinants of IT-Diffusion and IT-Use in Healthcare

- Development of Interactive Web Sites to Enhance Police/Community Relations