40 - Research

Editors: Goldman, Ann; Hain, Richard; Liben, Stephen

Title: Oxford Textbook of Palliative Care for Children, 1st Edition

Copyright 2006 Oxford University Press, 2006 (Chapter 34: Danai Papadatou)

> Table of Contents > Section 4 - Delivery of care > 38 - Quality assurance

function show_scrollbar() {}

38

Quality assurance

Harold Siden

Quality is never an accident; it is always the result of intelligent effort.

John Ruskin (1819 1900)

Case

Jessica was a 9-year-old girl with neuroblastoma, initially diagnosed at age five. She underwent bone marrow transplantation, but the disease recurred. Chemotherapy was begun, but had little effect on progression of the disease.

Still, the parents continued to pursue therapies oriented towards another remission and, if possible, cure. Several discussions were held between the parents and the Oncology team. Some members of the team agreed with aggressive therapy, while others recommended a palliative approach.

The idea of meeting the Palliative Care team was introduced, but the parents were not interested. When Jessica was repeatedly hospitalized and began developing pain that was difficult to treat, the parents agreed to involve the Palliative Care team, but only for the purpose of addressing pain.

Over a brief period of time, as Jessica became more ill, the parents developed a better relationship with members of the Palliative Care team, especially the social worker and the chaplain. Jessica's mother was willing to discuss some of her fears and wishes, but her father felt strongly that all discussion should remain hopeful. He refused to discuss a Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) order. Jessica's older half-sister thought that Jessica should be told the truth of her condition. The mother was uncertain about this, but the father felt that it would take away any hope, and further that Jessica could not handle it . Several nurses suspected that Jessica was already well aware of her situation.

Eventually, the family agreed to have Jessica transferred to a paediatric hospice, ostensibly for symptom management. Jessica died two days later. She was receiving oral morphine for pain and had a hyoscine transdermal patch placed to treat excessive secretions. She received intermittent midazolam as well. In the two days before she died she required frequent breakthrough doses of morphine via nasogastric tube, and the nurses notes commented on increasing pain .

The family was present when she died. Although no DNR order was ever signed because of the parents lack of agreement, when Jessica stopped breathing no attempt was made at resuscitation, and the family agreed to this when asked by the physician present. After her death a phone call was placed to the Oncology unit at the Children's hospital and to the general practitioner in the community.

The day after Jessica died, the parents spent several hours with the chaplain and the social worker. Members of the Palliative Care and Oncology teams attended the funeral, and the family expressed gratitude to the teams for everything that had been done.

When discussing the case at rounds the week after Jessica's death, the Palliative Care team felt that they had done a good job despite many challenges. Two months later, Jessica's case was reviewed by the Oncology team at a case conference with the pathologist and radiologist. They felt that there was no additional curative therapy that would have been of benefit, and that they would not have changed anything in the original treatment approach 4 years earlier.

The social worker made two bereavement visits in the following months, but could not do more because of staffing issues. She provided information about bereavement and community programs. The social worker reported that the visits went well and the family was coping with their grief.

Introduction

The case described above will sound familiar to anyone involved in paediatric palliative care, whether a nurse, physician, therapist or volunteer. The complexities of care and management are often striking. One of the key challenges both for the team and for the family is communication. Despite these challenges, many times teams and families feel that things went well . In the case described above, the family expressed their satisfaction to the team, and the palliative team acknowledged a sense of success.

Does this case, however, describe quality? Were the communication challenges dealt with effectively and will

P.574

there be any improvement the next time? What about the gaps in communication between the oncologists, the palliative team, and the community? Was symptom control ideal? Was there any measurement of symptoms that could provide feedback to medication administration, and will it have an impact on future cases? Was the bereavement and follow-up adequate, despite resource issues? Finally, were the review processes by the palliative team and the oncology team done in the best way possible?

These questions touch on some of the many issues that surround the provision of quality care in paediatric palliative care. The desire to provide high-quality care is inherent in our good intentions in working in this challenging field. A desire to do good to be empathetic to families in the some of the most difficult circumstances possible guides many of us. Busy clinicians work hard to stay on top of new literature and attend conferences to stay up to date. Isn't this enough to ensure that we are delivering quality, the best care possible?

Unfortunately, as the saying goes, the road to hell is paved with good intentions. Attention to quality conducted in a systematic manner at the organizational level is now a given within health care, including palliative care. Health care, however, brings special challenges to the application of quality concepts. These challenges are multiplied in the field of palliative care, and multiplied again in paediatric palliative care.

Paediatric palliative care practitioners are no strangers to difficult tasks, and while using quality tools may require effort, it is an undertaking that can be done well. Systems to judge quality are now required as fundamental within health care organizations. Beyond just fulfilling a requirement, organizations that engage in Quality Assurance (QA) and Quality Improvement (QI) processes find that their organizations and team members are better able to carry out their missions in this case, offering care to children and families living with life-threatening conditions. This chapter will review concepts regarding quality programs and describe how quality-based systems can operate in paediatric palliative care.

Definitions of quality a review of quality concepts in organizational theory

The term quality, as it has been applied for over 30 years in health care, has acquired a number of overlapping definitions in attempts to make it operational. There is no single definition, but quality can be best thought of as the effort to provide service at the highest possible level, according to the customers (clients, patients) needs. Specific uses of the term quality within health care will be the subject of this section.

Quality control

Quality measurement and Quality Control were initially industrial concepts, which grew directly out of the experience of mass production in large industrial firms. The Second World War and subsequent economic boom in the United States provided an opportunity to focus on Quality. The war effort required factories to efficiently produce war material in very high volumes. It was detrimental both to the military and to industry to have a high failure rate for equipment. War material was produced according to exacting specifications, so that multiple factories from different companies might all be involved in turning out similar material (e.g. standardized ammunition). For the government, Quality Control meant purchasing standardized items. For the armed forces, it meant having equipment that would function reliably. For the company, it meant increased profits by having fewer defects or rejects in the assembly line.

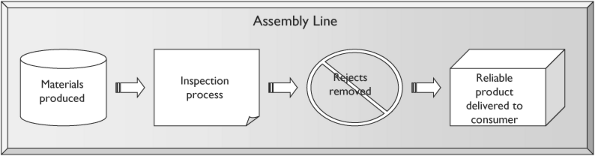

The resulting approach was Quality Control through inspection. In this scheme, the end product is carefully inspected for defects. Products that do not meet the pre-determined standard are removed at the end of the production line and either discarded or sent back for reprocessing.

In Quality Control, statistical methods measure acceptable defect rates. Companies determine how many defective items can be allowed to roll off the assembly line usually the acceptable defect rate is on the order of 1 10%. The organizational effort behind quality is put into improving the inspection and control methods available to industry, to ensure that fewer defective products get through the system.

Key features of the Quality Control system are that it accepts a specified error rate, that the standard can be determined by an external source, and that the standard set does not need to be improved upon, only met. In fact, there may be significant cost to exceeding, rather than just meeting, the standard. Finally, Quality Control is done at the end point of the manufacturing process defects are in the manufacture itself, and are not necessarily thought to relate to design (Figure 38.1).

Accreditation and quality assurance

Within health care, there are parallel systems to the Quality Control approach described above. Some of these health care approaches pre-date or are contemporaneous with the industrial Quality Control developments begun in the 1930s, while others arose later. The two most well known approaches within health care are the closely allied concepts of Accreditation and QA.

P.575

|

Fig.38.1 Quality control through inspection. |

Accreditation

Initial efforts to introduce quality concepts began with accreditation. External bodies certified and still do health care organizations as meeting pre-set standards. The most well known of these in North America is the American Joint Commission for Accreditation of Health Care Organizations (JCAHO). JCAHO started in 1951, and continues to provide standards and benchmarking for health care organizations. Approximately 17,000 organizations undergo the accreditation process through JCAHO [1].

Accreditation involves an agency undergoing review by an external group. The organization wishes to demonstrate that it can meet pre-defined standards in providing care to its patients/clients. Such accreditation, of which the JCAHO is only one example, extends to facilities, care processes, governance, and staffing. Often, such accreditation can be a requirement for licensing by a government body.

There are also accreditation schemes at the individual practitioner level; these include national, provincial, or state licensing bodies overseeing the training, licensure, and conduct of regulated professions. Professional quality begins with accreditation of initial and advanced training, as well as schemes for advanced certification.

One example of an accreditation system functioning at the level of the individual is physician licensing. The most basic licensure programs simply require evidence of completion of a specified medical training program and a minimum of post-graduate training, followed by success on standardized examinations. More recently, both medical school accreditation programs and specialty regulatory systems, such as American Boards of Medical Specialties or the Royal Colleges in many Commonwealth countries, have been requiring evidence of ongoing professional education through approved Continuing Education programs. Lastly, professional accreditation bodies take responsibility for setting and enforcing guidelines regarding professional-ethical behaviour. These approaches to professional accreditation are under scrutiny, both for their effectiveness and for their appropriateness.

Physician certification is only one example of a professional accreditation process, but similar schemes exist for other professionals in the field, including nursing, psychosocial support, expressive therapies and spiritual guidance.

Quality assurance

In the 1960s and 1970s, a broader health care quality effort, beyond accreditation and licensing, was introduced under the rubric of QA programs. An example of this trend is the Peer Review Organizations (PRO) approach, in which an external group of peers or experts examines the quality of health care practices. PROs function mainly within managed health care environments, especially American government systems such as Medicare/Medicaid. Their purpose is to reduce adverse outcomes and, at the same time, to make sure that resources are used efficiently.

Unlike basic accreditation programs, QA systems may focus on quality of care as evidenced through processes and outcomes. QA programs concentrate on using the resources and processes that are in place to ensure that quality standards are being met. These quality standards, however, are still set a priori and externally. For QA, as with accreditation schemes, if standards are being met then no further action is taken by the organization until the next review cycle. Features of good QA systems are that they are based on broadly accepted standards, they are usually characterized by voluntary compliance, and they have a functional orientation towards processes or resources. QA reviews should be undertaken regularly to ensure that a specific (usually minimum) standard is met.

The positive aspect of QA systems is that they are designed to reduce error and adverse outcomes, and do so in a way that can examine all aspects of care, not just endpoints. Moreover, because they rely on external standards, what is entailed in meeting those standards is very clear to the healthcare organization.

P.576

Finally, while resources need to be devoted to collecting and analyzing data, organizations do not need to reinvent the wheel by developing brand-new internal standards or tools for their evaluation.

The drawback of QA systems is that they are designed to help organizations meet a standard, without any incentive to exceed that standard, just like Quality Control systems. Furthermore, because they embody a pass/fail philosophy, they may be perceived as punitive. It is difficult for staff to generate ongoing enthusiasm for the time and effort required to meet standards that appear to be static and imposed from outside. Finally, accreditation and QA systems are driven by insiders in health care (professionals); there is no inherent linkage to the interests or requests of the consumers of health care patients and their families.

Quality improvement

Currently, when health care providers think of quality or Quality Control, they are probably thinking of Quality Improvement (QI), which is a distinct approach of its own. In the 1980s and 1990s, QA efforts were superceded in health care by the QI movement. There are a number of quality efforts that fall under this movement, including QI, Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) and Total Quality Management (TQM). For the purposes of this text, we will simply use the term QI to refer to these efforts.

QI was another direct import from the industrial world into health care, and continues to be the reigning paradigm for quality efforts within the field. In the 1950s a number of industrial innovators improved upon Quality Control methods to help companies improve their processes and turn out better goods. The most well known of these thinkers was W. Edwards Deming who, along with Joseph Juran, introduced advanced quality methods to the Japanese as part of the effort to rebuild their war-torn economy.

While Deming and Juran had differences in their approaches, especially in their use of statistical methods, both as well as other thinkers, including Kaoru Ishikawa emphasized the need for quality in each step of the manufacturing process. This emphasis begins right at design in order to produce the highest-quality goods. Consumers would provide feedback to companies by purchasing higher-quality goods, even if they cost more. Deming argued that consumers would focus on high-quality goods, and that if corporations maintained quality, then profits would flow secondarily but necessarily. Orientation towards quality, rather than profits, would actually make companies more successful in the long run.

Deming's name is the one most associated with this quality approach, and he is credited with reforming Japan's manufacturing sector. As part of this breakthrough in thinking, he also promulgated the belief that the standard for a product was not determined at the factory by engineers or managers, but by consumers themselves.

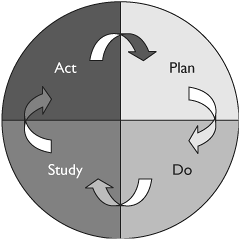

Another critical philosophical piece of Deming's thinking was the importance of an iterative or ongoing cycle of improvement. Not only were the needs of the customer the focus, the process also endeavored to constantly improve quality, thereby seeking higher standards at each iteration.

Therefore the characteristic features of QI are that: (1) The quality standard relies on the customer's assessment, and is not externally determined; (2) Quality needs to be inherent in the business-client relationship; (3) The goal is not just to meet a standard, but to continuously create new standards for the organization (so the quality effort is Continuous ); and (4) Quality requires examination of all aspects of the company (is therefore Total ). The basic QI process has become identified with the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle (Figure 38.2).

In practice, it is often found that managers best focus on one aspect of the organization at a time namely systems (resources and structures), processes (how care is delivered) or outcomes. One cannot focus on any single aspect exclusively, however, as the three are inter-related. For example, processes are often easier to examine, evaluate and quantify than outcomes, especially in health care. It still must be demonstrated that the resulting process evaluation is linked to better outcomes. A method that takes into account all three factors will lead to the most successful implementation of a QI program. This three-part framework of systems, processes and outcomes will be discussed further below.

By the late 1980s, as Japan's economic success took hold, corporations and then health care organizations began to adopt QI methods [2]. The shift from QA to QI in health care

|

Fig.38.2 The Deming Cycle:Plan Do Study Act. |

P.577

may represent not just the influence of the popular image of the Japanese success story, but also fundamental shifts in the nature of health care culture, especially in response to new large-scale managerial structures inherent in both the US managed health care systems and in the UK National Health Service reforms.

In accordance with current thinking, QI methods (CQI, TQM) are well-aligned with the goals of health care in that patient-oriented or family-oriented care is a philosophy that makes the patient's own perception of needs the arbiter of successful care delivery. Quality is therefore aligned with providing the patient with the kind/type of care that they perceive as important for themselves. In some settings, there is close agreement with provider interests; for example, in anaesthesia both parties would likely agree that safe anaesthesia, good pain control, and efficient delivery are important targets. In other areas of health care, determining desirable outcomes is more of a challenge, as will be seen in the discussion of particulars regarding palliative care.

QI and other quality methods found a ready home in certain sectors of health care. These areas are characterized by the routine use of highly standardized procedures where safety is a primary concern. One example already mentioned is anaesthesia, where many patients undergo the same procedure (e.g. the use of inhaled anaesthetics) repeatedly. While safety and patient outcome are important, so is efficiency because of its impact on operating room schedules. QI approaches are ideally suited to such settings. Therefore, there was a premium on developing standards and measurement tools to improve safety of care, efficiency of care and patient satisfaction. In these settings, resources can be readily delineated and processes described, while outcome measures, such as safe patient anaesthesia, are quantifiable [3].

QI has become so pervasive throughout health care that accrediting bodies, while originally operating from a perspective of QA themselves, are now requiring evidence of QI efforts within health care organizations applying for certification. Both the JCAHO in the United States and the National Health Services (NHS) Trusts in the United Kingdom require that QI processes be in place, in order for a health care organization to qualify for accreditation.

QI efforts should not be confused with cost-effectiveness or other management doctrines. Confusion can exist because of the methods of data collection, the use of the information for program evaluation, and the overlap of purposes; nevertheless, QI efforts specifically address quality issues. Deming saw quality as a fundamental target for organizations to meet, and suggested that other goals, be they profit or effectiveness, would flow from that (Table 38.1).

Table 38.1 Definitions of quality methods | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

P.578

Challenges of QI

As has been emphasized throughout the literature, implementing QI can be a challenge for organizations, although proponents argue that it has significant rewards. QI represents a fundamental philosophical shift for organizations, especially profit-oriented companies. Engaging in a QI process requires significant and ongoing organizational commitments, including the following:

Fundamental orientation for organization.

Leadership commitment.

Resources, often multi-year both money and teams [4].

Perception of the patient as customer who determines what quality means.

Recognition that QI is not the same as accountability for health care managers [5].

Acknowledgement that targeted issues/items are fundamental and important to all stakeholders.

It is important that QI mechanisms (e.g. the data collection method) must be easy to integrate into normal practice to enable ongoing support. If the process is difficult, or requires a large block of time episodically, it is less likely to receive continued support. Furthermore, the results of the quality system must be easily accessible, integrated into routine practices, and have an impact on function.

There is some debate regarding the role of a quality system manager the person responsible in the organization for the quality endeavor. In organizations where there is such a person, both leadership and supervision are embodied in that role. On the downside, all the responsibility for QI is placed on that person. They may begin to play the role of police , without other function. Another reason this role often does not work is that QI requires staff input and support but having a quality manager gives staff the message that quality is someone else's job.

An alternative is to spread QI responsibility throughout an organization, so QI becomes part of everyone's role. In high-functioning organizations, such diffusion enables QI to permeate all relevant groups and improves the opportunity for ground-level support. The challenge then becomes lack of experience in method, lack of commitment by all staff and all managers, and a diffusion of responsibility. This sometimes means that QI is no one's job. Thus, when QI is implemented at the level of managers and line workers, they need sufficient training in the philosophy and processes to allow them to carry out their duties. Furthermore, there needs to be a clear and consistent message from the senior management/leadership team that QI is an expected component of each of their roles.

Fundamental to either implementation is support for QI at the highest level of the organization. Leadership needs to see QI as fundamental to the organization; these activities cannot be put aside for other considerations, such as temporary crises, lack of time, and other new and exciting initiatives. They need to be seen as part of the day to day processes.

The time required up-front for initial buy-in by line management, and training and support, cannot be underestimated.

Quality initiatives in service organizations

This section will review how quality concepts have been introduced into health care as a general field. It has been noted that the non-profit sector poses different challenges for QI from profit-based organizations. In business, revenues and profit serve as final standards for the success/failure of any given QI activity. Service organizations must choose different bottom-line targets. Peter Drucker and other management thinkers recognize that all businesses have one thing in common success measured as profit. In contrast, service organizations do not have any such common denominator [6, 7].

For both QA and QI activities, the ability to measure outcomes is a core component of the method and a critical feature of evaluation. Since there is no simple common denominator, service organizations must generate their own. There are a number of approaches for this, and unfortunately, no simple answer. That does not mean that service organizations can opt out of undertaking quality initiatives, only that they must be more creative and thorough in their efforts. Measures may be shared by organizations across a field of activity for example, common outcomes determined for all hospitals. Measures may instead be specific for an individual organization.

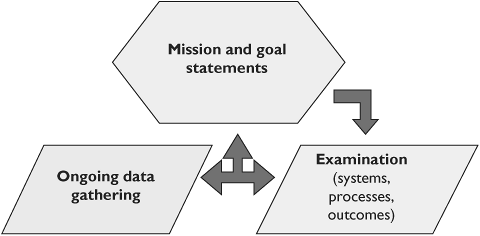

The most effective way for organizations to generate these criteria, and to do so in a manner that is internally consistent, is to rely upon mission and goal statements. Missions and goals are generated at the highest level of the organization, usually the Board of Directors, and can thus be thought to represent the fundamentals for the organization, as well as provide some evidence that there is actually backing from leadership for the initiative. Mission and goal statements set out the core targets for the organization, in the same way that profit is the core target of a business. Figure 38.3 shows how mission and goal statements become the foundation of a quality criteria development process.

P.579

|

Fig.38.3 Steps to developing quality criteria in health care. |

Quality initiatives in healthcare organizations

Vague terms such as serving our clients,' improving the environment, etc., do not generate measurable outcomes. Therefore, generating appropriate mission and goal statements by non-profits is a critical activity that is in turn linked to any QI endeavor. A mission statement and organizational goals document form the basis from which quality approaches can be derived. Boards must take this activity seriously, and commit the organization to working within the framework.

There has been a significant amount of work specifically addressing quality measurement in health care [8, 9, 10, 11]. Two of the leading thinkers, Avedis Donabedian and Robert Maxwell have provided a framework for thinking about quality within health care [12, 13]. Donabedian proposed that quality in health care is multi-dimensional, and relies upon the goodness of three factors technical care, interpersonal relationships, and environment.

Technical care encapsulates all the skills of providing care, and is directly related to the effect of care on outcome. The technical component may be more than direct hands-on care for the patient; it may include support items, such as the availability of training for the staff to guarantee clinical excellence. The second factor, interpersonal relationships, is challenging to measure but is a crucial component of satisfaction with care and social concepts of quality. Again, interpersonal relationships is a broad concept, not limited to doctor-patient or nurse-patient interaction. It includes relationships within and between teams, the quality of information-sharing practices, and the warmth and caring experienced by the patient. Finally, there is the environment. Often this is thought of as the physical environment, but may include other aspects, such as technology, that enable care.

For each of these three aspects of care, Donabedian proposed that quality schemes look at systems, processes, and outcomes in a framework that has been widely accepted. These items became the framework , or lens, to examine the dimensions of quality [14]. Systems refers to the underlying resources, programs and administration that enable the organization to function, or enable a particular component of the organization, for example, nursing care, to function. Processes are all of the items and activities involved in providing care. Outcomes are the results of that care, examined in measurable fashion.

These dimensions should not be thought of as rigid instead there is interplay between them. It is up to the manager or evaluator to determine how an item should be classified in order to enhance an understanding of the impact on Quality. For example, providing safe sedation for painful procedures can be thought of as an outcome in a day treatment setting. Alternatively, it may be examined as a process leading towards another outcome such as successful endoscopies with earlier diagnosis of cancer.

Robert Maxwell has taken Donabedian's analysis further in examining quality care [13 15]. He has provided six dimensions of quality in health care activities. These dimensions, or questions, expand the concept of quality, and have been used in analysis in the United Kingdom [16]. The dimensions Maxwell uses are:

Effectiveness of the treatment based upon evidence.

Acceptability is the treatment acceptable? Is it provided in a manner that patients find acceptable?

Efficiency especially in the use of resources for benefit obtained.

Access what are the barriers and opportunities for using the service?

Equity are all patients and groups being treated in a fair and equal manner?

Relevance how does the service relate to the group of patients and to society as a whole?

As is pointed out by Donald and Sally Irvine, there is a great deal of overlap in these concepts and in quality concepts from other authors and groups [14]. Specific terms may be different, but overall the concepts show great similarity. It is important for health care organizations to use these concepts as broad guidelines, and to assist evaluators in making sure that all relevant dimensions are considered. There is not a cookbook recipe that must be rigidly followed in every given examination of quality.

While the concepts underlying quality are clear, application is difficult. Ideally, one examines systems, processes, and outcomes as a unified entity. Limited resources may tempt one to examine only one of these items, but such isolation does not

P.580

lead to effective evaluation. For example, evaluating systems alone is challenging in that underlying systems are fundamental components of organizations, and their characteristics may be elusive for insiders to recognize. In turn, there is a natural temptation to evaluate processes alone, as they readily lend themselves to examination much as manufacturing took the blame in Quality Control where there was an unwillingness to examine design and engineering. Similarly, looking at outcome can have pitfalls. In some areas of health care, it is tempting to isolate outcome as treatment success or improved survival.

Researchers are beginning to examine more sophisticated concepts, such as quality of life resulting from treatment. This is especially true in treatments that may provide longevity, but with the burden of ongoing limitations in activity or health challenges. Improved survival may be an overly simplistic criterion, even in such fields as surgery.

In other specialty areas of health care for example, those dealing with chronic illness, and especially palliative care outcomes may be very challenging to measure. Outcome in these areas is generally taken to be at least congruent with patient satisfaction. As will be seen below, it is not always clear that satisfaction is a static concept, or that it is easy to measure.

Taking into consideration the perspectives of the many different stakeholders is a further difficulty. For some time, the opinion of clinicians was assumed to be the relevant data source for quality efforts. This was especially true for QA, where the standards for quality are based upon expert peer opinion. QI, as taken from Deming's work (and in light of health care consumerism) has brought the perspective of the patient to the discussion. Determining who the consumer is (the individual patient, the family, the social group, the health authority); when they should be included (right at the time of treatment, months to years later); and how evaluation should be conducted (quantitative versus qualitative approaches) is a process that is still unsettled.

Despite these challenges, quality efforts in health care have provided positive results. There is now increased thinking about the aims and objectives of health care initiatives. Patient perspectives, albeit difficult to engage, are now taken seriously in discourse. A QI process, with its combination of inductive reasoning and evidence gathering, is well aligned with the scientific approach inherent in modern health care. QI methods enable evaluators to look at the broadest possible picture from specific treatments to wider questions about resources and goals. A well-functioning quality process may help develop alternative approaches for organizations to achieve their ends, rather than simply trying to eke further benefit from traditional practices.

Case

A hospice team in Canada undertook an audit of the use of pain medication. They found that analgesics were frequently prescribed for children during hospice stays based upon pain assessments with standardized tools. Initially the team thought that this represented a satisfactory approach.

Further questioning of families, however, showed that many parents found the system quite cumbersome after discharge, and that there was a delay of several days for getting refills. Often, community pharmacies did not carry the medication in suitable form, and it would have to be specially ordered. Some Family Doctors (GPs) did not have opiate prescribing licenses, or did not feel comfortable prescribing high dose opiates for children.

The hospice team devised a new method, whereby once a stable dose was determined, the hospice physician would order a 30-day supply. In addition, a fax copy of the hospice prescription was simultaneously sent to the family's GP and community pharmacy, to inform them of the drug and dose. This gave the GP immediate information, and provided the local practice and pharmacy with time to make arrangements for refills.

Careful consideration of systems, processes and outcomes, with a focus on end points as defined in missions and goals, reveals that there may be a host of options for fulfilling or achieving those goals, some of which may not be apparent at first.

QA in hospice palliative care programs

Moving from the broad field of health care to the specific area of hospice palliative care reveals important considerations about how to implement quality. Discussion regarding quality emerged within the field of (adult or general) hospice-palliative care by the early 1980s [17, 18, 19, 20]. Discussions focused on Quality Assessment and Assurance activities, while initial standards were being developed in hospices [19]. In the United States, the activities of the National Hospice Study establishing cost-effectiveness also enabled an initial determination of standards in order to support the development of Medicare reimbursement policies [21, 22, 23].

Currently a number of organizations exercise influence in setting quality-based standards for hospice-palliative care. Some organizations, such as JCAHO, conduct accreditation activities for many types of health care organizations, with hospices considered a sub-set. Accreditation is inherently a QA exercise, but by including a requirement for QI efforts within the standards, the JCAHO has guaranteed that organizations will be functioning at current levels of program evaluation sophistication.

Freestanding hospice accreditation is not, however, equivalent to QA/QI for all palliative care programs, since programs that are hospital- or community-based may not be included in the umbrella. Organizations such as the Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Organization have promulgated

P.581

national standards for providing care in these settings as well [24]. These standards provide both principles and norms for the provision of hospice-palliative care.

In the United States, standards have been developed specifically for hospices, including those of the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization [25]. The United Kingdom has established standards through the National Council for Hospice and Specialist Palliative Care Services [26]. Other countries for example, Australia have proceeded along similar lines [27]. In all cases the guidelines and standards are voluntary. They begin, however, to establish frameworks and principles that individual hospices/palliative care organizations can refer to when seeking to provide quality care.

QA systems palliative care professionals

We move next from the level of the organization to the level of the individual professional. Standards are under development for professionals, mainly through Quality Assurance and accreditation approaches. Less stringent requirements have been developed for volunteers, who are the backbone of many palliative care programs, but there are some guides.

Professional quality begins with accreditation of initial and advanced training, as well as schemes for advanced certification. The American Board of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, for example, provides a voluntary system for certification through examination of expertise in the field of palliative medicine. In the United Kingdom, there is now Royal College specialty certification in Palliative Medicine, which requires four years of training in the subject. Similar systems have been developed to include Family Practitioners (e.g. Canadian College of Family Physicians). All of these systems have examination requirements and set standards for ongoing education. Palliative care programs themselves, in lieu of external professional body certification, can establish standards whereby professionals participate in a minimum number of hours of professional development annually.

QI in palliative care

In an ongoing shift, there has been increasing interest among researchers to use QI in palliative care. This has been driven by a number of factors, including increasing sophistication of quality methodology mechanisms. There are external forces at work, including the development of service purchasing in the United Kingdom and managed care in the United States [28, 29, 30]. One important conclusion that must be drawn from these initiatives is that quality efforts are often challenging, and those in the field of palliative care especially so. When undertaking quality initiatives, palliative care organizations cannot underestimate the amount of time, money and effort that needs to be devoted to this area. For example, one well-conducted QI effort in pain management in a hospital required a dedicated team, several hundred thousand dollars and many years to complete [4].

Concepts and tools used for quality initiatives in palliative care

Hospice-palliative care programs will find several tools useful in implementing QI programs. As noted previously, quality begins with the development of missions and goals by program leadership. The second step is to determine specific areas in which to implement quality tools. Ideally, all aspects of the program can be evaluated through a quality lens; however, given the resources required, usually only specific, high-impact areas are chosen. However, it is not entirely clear is whether efforts by academic research teams have been replicated in the day-to-day function of typical palliative care programs.

For a palliative care hospice team wishing to undertake a quality effort, several decisions need to be made early on. An initial determination needs to be made regarding the item of concern. Usually this can be gathered through an internal process, whereby staff discuss issues that they feel need to be addressed. This discussion emerges through routine feedback processes, such as staff meetings, and is reviewed at the program leadership level. A less satisfactory approach is to have the item selection imposed externally through an accreditation body or other external agency. The latter method means that the selection is imposed and may not fully engage the staff it also may not correctly identify the highest-need areas.

A second stage is to more formally assess the area or issue of concern. Typically this takes place with a structured process, sometimes a meeting or retreat, to confirm that the targeted subject is the correct one. Confirmation from program data, a brief literature review, and basic comparison to similar institutions is useful at this step. Because of the resource-intensive nature of quality efforts, it is incumbent upon program leadership to make sure that the focus of the effort be an important one for the program. It must be a core item for the program, worth pursuing and not peripheral.

Because of the nature and focus of palliative care, attention has been focused on two areas: symptom management and interpersonal relationships. These aspects of care are core to the goals of palliative programs and thus have been the focus of evaluative research. Moreover, they are areas where researchers can examine outcomes and then readily correlate these to processes and systems. Examples include pain management [31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36] and professional communication [37, 38].

P.582

The next stage involves deeper and more focused investigation. Resources within the program need to be devoted to the quality effort, even when an outside consultant is brought in. At this stage a more formal effort is initiated to address the area of interest examining structures, processes and outcomes. It is often tempting to examine only a single factor (e.g. processes), which seems easy both to measure and to change. That, however, will not fully explain the problem, nor will it guarantee any change in outcome. All three dimensions are linked, and all require attention in the evaluation plan. Another temptation is to focus on outcomes at first. This is problematic if it does not take into account the significant resources that will be required to examine and make changes in systems and processes. Moreover, within palliative care, outcome measures are still problematic, as will be discussed below.

The field of quality in palliative care, while still in its early stages, is now developed enough that there are tools for data gathering both at the initial stage, when trying to define the problem of interest, and at the subsequent stages of the evaluation cycle when carrying out the QI effort. There is also increasingly better understanding within palliative care as to how these tools can be used together, both quantitative and qualitative, as well as the limitations about the data they gather.

Familiar data-gathering tools include focus groups [28, 37, 39, 40], surveys [32 41 42], clinical audits and report cards [43 44], and mortality rounds and end-of-care debriefings [44 45]. While there is an initial temptation to use surveys, it may be better to start with less structured tools for data gathering, including patient interviews and focus groups. These approaches may yield more detailed information (the term sometimes used is rich data ) about the program and patient experience. [46]

Qualitative data methods are well accepted, especially for their ability to generate new theory, identify unexpected issues, engage multiple stakeholders, provide highly valid data (but not necessarily data that is reliable or generalizable according to standard psychometrics) and give participants a voice. [47] In palliative care, where so many complex dimensions interact, and where the experience for each subject (patient, family, community, and caregiver) is very personal, qualitative approaches are important tools in quality efforts.

The other tools described above, such as rounds, clinical audits, and end-of-care debriefings, should also be utilized. For example, at one children's hospice a dedicated debriefing round takes place following each death [48]. These sessions involve all members of the care team, and include professionals from the hospital and the community as well. A summary of the child's history is undertaken, as well as a review of management including medicine-nursing, psychosocial, spiritual care and co-ordination of services. Included is a review of care that went well and care that did not, with recommendations for change in the future. Minutes of these sessions are generated and the results are shared with all members of the care team. The full set of these rounds is maintained for periodic review. This is one example of how a clinical audit practice can be incorporated into a QI program.

Quantitative tools can be especially useful in palliative care processes and system resources; however, when it comes to outcomes they are less useful (with the exception of survey instruments). This is due to the fundamental properties of the goals of palliative care, which are oriented towards symptom relief and providing a comfortable and dignified death. In other health care fields, quantifiable outcomes are easier to identify for example, length-of-stay data, survival data, cure rates, etc. In palliative care, the single common outcome is death, and therefore survival and related quantitative measures are not relevant data items. Surveys and, in some settings, qualitative approaches, can help to access data on outcomes of interest, such as quality of life and satisfaction (Table 38.2). These aspects of assessment and data gathering raise a number of issues for QI in paediatric palliative care that will be discussed further on.

Tools addressing symptoms and satisfaction

Despite these reservations, a number of quantitative tools have been developed within the field of general and adult palliative care to assess symptoms and satisfaction. Of the dozens of tools, some examples include the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire [49], the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale [50], and the Quality of End-of-life care and Satisfaction with Treatment (QUEST) scale [51]. Surveys cover all aspects of care, including symptom management, psycho-social care, spiritual care, and bereavement. The Toolkit of Instruments to Measure End-of-Life Care (TIME) provides a current web-based bibliography of numerous tools to measure multiple aspects of care and of quality of care in palliative medicine. Although survey development can be lengthy and resource-intensive, it is important to remember the imperative of validating the instruments using appropriate techniques [52].

Table 38.2 Qualitative and quantitative quality-measurement tools | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

P.583

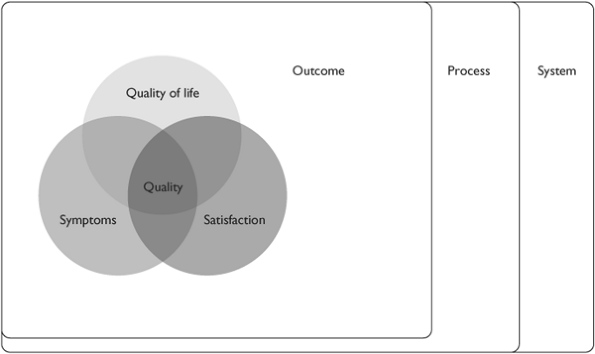

Most of the instruments described above measure either symptoms, quality of life, satisfaction with care, or a combination of factors from each of these domains. In turn, since symptom relief has been used as a proxy outcome measure, these instruments have become important in addressing quality issues within palliative care.

Morita and colleagues developed a 34-item questionnaire in rigorous fashion to explore factors that related to overall satisfaction with care [42]. The assumption is that satisfaction with care becomes the arbiter of quality of care, from the standpoint of the patient and family. This group identified seven dimensions:

Nursing care warmth, care help, support

Facility the physical layout

Information explanations and communication

Availability of hospice care

Family care and support

Cost

Symptom palliation.

For each of these domains, there is a relationship to performance in care, based upon (1) competence, (2) effectiveness, (3) accuracy, (4) attitudes of professionals, (5) the strength of communication, and (6) variables pertaining to the organization.

Tools addressing outcomes and quality

There have been attempts to create scales that address quality and outcome as primary measures, rather than through secondary indices. The tools used in these approaches have undergone testing for reliability and validity, and describe outcomes of value to families and practitioners. Research so far has concentrated on adult palliative care, though there may be some extrapolation possible to paediatrics.

Much of the work in palliative care has been undertaken by Irene Higginson and colleagues in the United Kingdom, and by Joan Teno in the United States. One instrument designed specifically to examine dimensions of quality in palliative care is the Support Team Assessment Schedule (STAS) [53, 54]. The STAS is a measure specifically developed to measure key indicators in the delivery of palliative care [53]. It has been used in both community and in-patient settings. The domains in this tool include:

Pain and other symptoms

Patient distress

Family distress

Communication with health professionals

Directly obtaining practical aid.

These are measures of patient outcome while participating in hospice care. This schedule needs to be adapted to paediatrics, and some challenges to its reliability will need to be addressed [55]. There are conflicting reports about the ability to use it in different cultural or social settings [56, 57]. Nevertheless, the domains are still useful in developing a model of quality.

Another audit tool, currently under development, is the Palliative Outcome Scale, which examines care from the standpoint of both the team and the patient [58].

Challenges and successes in quality efforts in palliative care

There are myriad challenges related to quality efforts in palliative care. The first relates to determining outcomes. While there is general agreement that palliative care addresses comfort and dignity at the end of life, beyond that there is little agreement regarding the tools that enable outcome assessment both because it is difficult to measure (quantify) these aspects, and because of the multiplicity of subjects (patient, family, providers), whose experiences change over time through the illness-dying-bereavement trajectory. Also, it is difficult to determine when data should be collected during the entire palliative phase, at end of life, in early or in late bereavement. To summarize, there are challenges in assessing the who, the what and the when of palliative care in order to determine quality of care.

The first problem for either quantitative or qualitative approaches to assessment is determining the recipient(s) of care (patient, close family, extended family, significant others) and in turn who the respondent is to address aspects of that care. Even in the simplest formulation, where the recipient is the patient and care is focused on symptoms, problems arise in evaluating quality. Unlike other areas of biomedicine, the only gold standard for symptom relief is the patient's experience of the symptom (e.g. pain, dyspnoea, anxiety). There are a number of potential respondents who can assess the symptom the patient, the family, or the professional care provider. Researchers have begun to evaluate the strength of correlation between patient, family (caregivers) and professional assessments of both symptoms and of satisfaction. The literature indicates relatively poor correlation between patient'sand caregivers assessments of symptoms [59]. In this sense, caregivers even close family members are not legitimate proxies for patients.

The nature of palliative care requires that the patient experience is a primary outcome of the goals of palliative care.

P.584

|

Fig.38.4 Dimensions of quality of life, symptoms, and satisfaction. |

Thus, as researchers have attempted to assess symptoms or satisfaction with care at one of the critical phases of the end-of-life journey, there has been a significant challenge in that other individuals cannot provide valid information for the patient's experience.

For outcome data, determining when data is collected is a second difficulty: during care before death; throughout program involvement or only during inpatient periods; or after death. Patients may be too ill or fatigued to participate in surveys, assessment tools or interviews to provide evaluation data at the end of life [60]. An alternate approach may be to focus on the experience of family and caregivers as they experience the patient's dying and death. For these groups, timing of assessment is an important issue; questions arise as to the best time that grief and bereavement data can be collected. In at least one study, there was a preference by family not to be interviewed until more than six months had passed [39]. The role of grief and the impact it may have on family perception of satisfaction, symptoms and quality requires further exploration.

The next emerging challenge is deciding what to study. There is now recognition that the items of importance to patients regarding palliative care may be distinct for different patient groups. In one study, the goals for palliative care of patients with Chronic Pulmonary Disease were different from those with AIDS and cancer [61]. The implications of this for paediatric palliative care are significant, and challenge any assumptions of using or borrowing tools originally developed in adult palliative care or for cancer-based models of palliative care.

Other interesting findings have come out of this research, including the apparent realization that not only may there be poor correlation between patients and caregivers perceptions of symptoms, but more crucially, that patient symptoms may not correlate with satisfaction. In several studies, patients have poorly controlled symptoms and yet express satisfaction with care [32 51 59 62]. The reasons for this require further investigation.

In summary then, there are several overlapping constructs, all of which can be thought to be component parts of out-come for palliative care (Figure 38.4). These constructs include, but are not limited to, comfort and symptom management; care for the family both during the palliative care phase and after death; satisfaction with care for patients and for family; and quality of life. All of these constructs are patient-centred or family-centred. There are other outcomes of relevance to hospice-palliative care organizations at the program level that may be reflected in costs, activity-levels, coordination of care with other agencies, etc. that may be important to study.

Even at the patient-centred level, there is no single construct that can encapsulate outcomes. These constructs interact with each other in complex ways that the quality researcher and program evaluator need to be aware of when establishing a QI program.

The conclusion, therefore, is that measurement of some but not all of the key outcomes in palliative care may be challenging, especially during critical phases. Outcome data are not conclusive; because of the methodological challenges it has been difficult to specify the outcomes that best track program success. In turn, this makes overall quality assessment and improvement difficult, but not impossible. Nevertheless, the overall data points to high degrees of satisfaction on the part of patients, family and providers with palliative

P.585

care. Trends in the field towards comprehensive symptom management, flexibility in care, and care in multiple settings, are all consistent with evidence at this point.

Most of this discussion has emphasized issues regarding outcomes. The framework established by Donabedian and Maxwell, however, included processes and systems. Here the data are much clearer. Processes lend themselves to study because they often have measurable activities, and sometimes external benchmarks. Examples of process evaluation for a hospice-palliative care program include time from referral to first visit, communications (e.g. time to get a letter out), and time for pain medication to be delivered to bedside [38, 63, 64].

One of the single most important process items correlating with satisfaction in care is the nature of interpersonal communications. There are important implications of this work for paediatrics, which will be discussed below [37, 61, 65]. Prognosis information, and symptom management are also critical items linked to satisfaction with care [66]. It should be noted that these items can actually be thought of either as processes or as (intermediate) outcomes. The distinction is not as critical as understanding their link to quality.

There is less information regarding the underlying systems or resources that are required to implement effective palliative care. There are common components of palliative care programs addressing the multiple dimensions of care for example, physical symptoms, psychosocial issues, and spiritual care.

There are standards and norms documents for hospice-palliative care specifically addressing paediatrics, which shed some light on systems. In the United Kingdom, the National Council for Hospice and Specialist Palliative Care Services has published a set of standards, which apply to all hospice-palliative care programs [67]. Similarly, there is a current norms document set forth by the Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association [24, 68].

The standards outlined in these documents cover broad areas related to patient and family care:

Disease management

Physical issues

Psychological issues

Social issues

Spiritual issues

Practical issues

Preparation for death

Loss, grief and bereavement.

Similarly, there are domains for:

Process of providing care (e.g. assessment and information sharing)

Governance and administration

Program support.

While these documents are an overview for a national approach, and are not specific to paediatrics, they contain specific information regarding items in care provision processes, governance, and administration and program support that may be of value to paediatric programs (Figure 38.5). In assessing and improving quality, programs will likely assess outcomes and process first, and determine whether systems exist to support these.

|

Fig.38.5 Pediatric palliative care standards. |

Quality efforts in paediatric palliative care evidence base in paediatrics

Moving from the overall area of (adult) palliative care to the more specific area of paediatric palliative care, the evidence base narrows. This is especially true when looking at quality concepts, where relatively little work has been done, and thus there is a need to extrapolate in the first place from the general (adult) palliative literature.

A number of challenges exist to developing quality standards for paediatric palliative care. One is that the field is still relatively young. The first hospice program specifically for children opened in 1982 [69]. Currently, there are almost 40 paediatric palliative care programs/hospices in the United Kingdom, and 10 in Canada [48 70 71]. In Poland there is a community-based palliative care program. In the United States, as of 1998 approximately 180 organizations provided some level of paediatric palliative care, across a variety of types of programs. Most of these programs took care of 12 or fewer children per year [72]. There are still only two free-standing paediatric hospice programs in North America at this time, and many programs are hospital-based teams [73]. The field has received increasing attention, but is considered to be in its early stages.

Given that the field is in its early development, one challenge is gathering sufficient data to support the development of

P.586

quality endeavors. Nevertheless, there are successful developments on two fronts one being research into the dimensions that are important to families and children in palliative care, and another being the recent publication of initial standards for paediatric palliative care.

Characteristics of paediatric palliative care, described elsewhere in this text, make it quite different from adult care. Notably, the illness models are different. Acute, severe, life-threatening illness makes up a smaller proportion of care for paediatric programs. Longer-term conditions, many of them genetically based, are a large proportion of illnesses. For example, at Canuck Place Children's Hospice in Vancouver, Canada, some 75% of children have diagnoses other than cancer, and similar data is found in the United Kingdom [74 75]. Included are children with neuromuscular diseases, syndromic disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, metabolic disease, HIV/AIDS, inoperable cardio-pulmonary diseases and poorly characterized CNS conditions with Severe Neurological Impairment, which carry a higher mortality risk [76].

A characteristic of these conditions is that prognosis is often difficult to predict, and many children live for many years with these conditions. They therefore require not measures designed to ensure death with dignity but instead life-embracing actions within the context of a shortened life span.

Another crucial feature of all paediatric health care encounters is the developmental nature of child health. Different strategies and approaches need to be used for distinct developmental phases. These approaches require constant revision as the child grows and changes thus they are not static for a given child. In turn, one must take into account the variation within a paediatric population, from the rapid changes of infancy, the emotional growth inherent in adolescence, and the distinct issues for those children whose development is not typical.

While the challenges for outcome measurement via proxy have already been discussed in regards to palliative care symptom management, there is an additional challenge in paediatrics, namely who is the patient and who speaks for the patient? These are separate but inter-related questions.

Who is the patient? Is it just the child; the child and parents; or the child, parents and siblings? Most definitions go at least this far, although one must also consider the importance of extended family and of close friends. The latter is especially important to adolescents. The issue is not just pertinent in the interpretation of experience for the pre-verbal or non-verbal child. It is also an issue that is developmentally relevant as children only acquire their own voice in establishing autonomous decision making over time. That task is one of the major functions of healthy adolescence, and is only made more complicated within the context of illness.

Thus there are challenges in undertaking quality-related research and evaluation in paediatric palliative care. A modest amount of work has taken place, but at this time there are no reports of comprehensive QI efforts or outcomes research in paediatric palliative care programs, per se; much of the existing research looks at specific symptom management or aspects of care.

In studies that have asked parents directly about their children's care, or have examined the care of children in detail, a number of areas are highlighted where quality measures can have an impact. One is the area of pain management. It is now well documented that pain assessment and treatment is a significant issue in child health. Studies have shown that overall pain management is poor in the paediatric population [77]. Recognition of symptoms and management is a basic foundation and has been highlighted as lacking in the care of dying children [66].

Several dimensions have been found to be very important to families and would be core components of a more global, patient/family-centred quality effort. Studies indicate that the most significant dimension may be good communication with health care providers. In one study, this factor seemed to closely link to satisfaction and had the largest impact on parent's perceptions of the quality of the care for their child [78]. Other factors have been identified as well that link to parent perceptions of quality. These include best-possible prognostic information, respite care, grief-support for losses long before death, coordination of services, equal opportunities for education and recreation, psychological support, sibling support, and efforts to address spiritual concerns [40, 79, 80].

In a study of satisfaction of parents with hospitalized children (not necessarily palliative), parents noted problems with discharge planning as another important component. It is likely that discharge/transition planning will turn out to be important to families experiencing hospice-palliative care [40]. In an investigation looking specifically at quality in paediatric palliative care, three other issues were identified as linking to family perceptions of quality: meeting the needs of siblings, care for non-English-speaking families, and providing bereavement follow-up [80].

Models and standards for paediatric palliative care

While there is no reliable evidence base regarding systems, processes or outcomes in paediatric palliative care, standards documents have been developed. Usually, these standards are generated through expert consensus and review of best-available evidence. These standards documents can form the basis for an individual program's QI effort by laying out dimensions

P.587

and targets for quality. These emerging standards will also provide a framework from which evidence-based research and evaluation can be launched.

The existing documents either describe ideals for care, make recommendations, or set forth explicit standards. They are inconsistently evidence-based in their standards and recommendations [81]. At least one of the documents links the promulgated standards to outcomes and indicators, in a US federally funded project for comprehensive children's palliative care [82, 83]. Some of the documents propose broad norms, while others set forth explicit and specific standards [67].

Examples of national and organizational standards for paediatric palliative care include statements by:

The Association for Children with Life-threatening or Terminal Conditions and their Families (ACT) in conjunction with the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health in the United Kingdom [67].

The American Academy of Pediatrics [81].

The National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization Administrative/Policy Workgroup on Children's International Project on Palliative/Hospice Services (ChIPPS) [84].

The Standards of Care for PACC (Program for All-Inclusive Care for Children and their Families) developed by Children's Hospice International (Alexandria, Virginia) and the Health Care Financing Administration of the US Department of Health and Human Services [85].

The Standards of palliative home care for children in Poland [86].

The Association of Children's Hospices.

Pediatric Hospice Palliative Care Guiding Principles and Norms of Practice developed by the Canadian Network of Palliative Care for Children and the Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association [87].

All of these documents share common features and cover a common set of domains, which is not surprising. Domains held in common throughout these documents include:

Patient- and family-centred care

Pain and symptom management

Developmentally appropriate care

Respite for families

Bereavement services

Continuity of care

Integrated, multi dimensional care

Professional competence and continuing education

Research

Care for caregivers

Policies and procedures

The various domains addressed in these standards documents are described and compared in Table 3 using Donabedian's framework as an organizing scheme.

In addition to the core domains, additional statements within these standards include:

Early initiation of symptom management in the course of a disease

Inclusion of children with any kind of life-limiting condition

Avoidance of rigid distinctions re cure vs. palliation

Early discussion of palliative care.

Many of the models of care for palliative care and for paediatric palliative care have not been directly tested [28, 87], and the need to test the individual components is great. Nevertheless, there is a move towards creating standards, both evidence- and consensus-driven, which in turn provide a framework for further QI and research activities. Areas such as team members [88] and spirituality [79] are being addressed.

While most of the standards and norms documents in paediatric palliative care provide high level guidelines for Quality, one program has specifically addressed Quality (via QA) within children's hospices. The Association of Children's Hospices in the United Kingdom recently produced a QA tool designed specifically for children's hospice services. This tool was derived from a wide ranging consultation with users of children's hospice services regarding what they value about children's hospice care, coupled with information provided by staff working in and professionals working alongside the children's hospice services. This consultation generated six key aspects: Access; the Child; the Family; the Staff; the Environment and Communication. The QA package is designed to enable a children's hospice service to self-evaluate their performance against criteria developed from material gathered through the consultation. The toolkit is being readied for publication and dissemination; how it will apply outside of the United Kingdom, and in palliative programs that are not hospice-based, remains to be studied (Table 38.3).

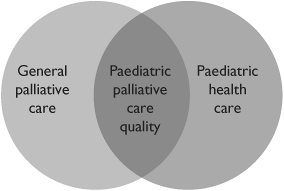

Creating a model of paediatric palliative care quality

Based upon the above documents, one can create a model for paediatric palliative care provided in a quality manner. Each program must undertake this task individually, but at the same time needs to be aware of the significant pitfalls of attempting to do this alone.

P.588

P.589

Table 38.3 Standards and outcomes in paediatric palliative care | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

P.590

The pitfalls are not limited to the expenditure of unnecessary effort where standards and methods have already been recreated that is, reinventing the wheel . An additional pitfall of developing a quality approach alone is that inadequate tools may be used, generating false answers [52]. The practice of quality in health care is now sufficiently developed that one must be working at a fairly sophisticated level in ensuring that valid and reliable tools are used to measure activity to meet guidelines and standards [13, 15].

Another pitfall that must be addressed is integrating the quality effort into the routine of the program or organization. The overall effort that must be devoted to quality endeavors cannot be underestimated [4, 89]. Furthermore, there is a risk of using assessment tools that have been developed in one setting, and assuming they will work in a different one [57]. Lastly, some techniques of assessment and measurement that work well in research settings are not always easily implemented in day to day functioning, and need to be adapted [89].

A working model of quality for paediatric palliative care would have a number of features: first, it would rely on one of the current guidelines/standards as a basic framework. Alternatively, new guidelines may be developed, but the evidence so far indicates that they should include a combination of systems, processes and outcomes.

Systems include a care team with a complement of providers skilled in symptom management, psychological and spiritual support, family support, and a facility or other means to provide respite. In addition, systems include appropriate governance and administration.

Processes include an intake mechanism, assessment of child and family needs, care for those needs, and a communication process for both families and other health care teams. Outcomes should be assessed in a multi dimensional fashion, relying on both the organization's published mission statements and external guidelines. In turn, these outcomes should be assessed taking into account the perspectives of the patient, the family, the palliative care team, and external teams at multiple points in time, both pre- and post-death. Methods should include both quantitative assessments of physical symptoms and satisfaction through surveys, as well as qualitative approaches, including interviews.

A formulation that takes into account multiple aspects of the patient-family experience may yield the best results. This may be especially important in paediatric palliative care, given the added issue of the non-verbal population and developmentally linked assessment. In this formulation, assessment is made of symptoms by patient, family and professionals, of patient satisfaction, of family satisfaction, and of carer perspectives [90].

Second, the items chosen would be consistent with the organization's mission and objectives statements. The systems and processes needed for an in-patient hospice program, a community-based palliative care program and a hospital-based team may be different.

Third, the quality approach would be built into the way that care is provided, with an active feedback loop from the quality system into the care system. The inherent nature of quality is one that has been emphasized. It must have an impact both at the assessment level, as well as at the day to day care level [15].

Case

Example of Quality Process Canuck Place Children's Hospice

One example of an implementation of a quality process is at Canuck Place Children's Hospice, in Vancouver, Canada. While not a complete process, it includes a number of the significant items described above. The quality process is outlined in the basic Strategic Directions of the Hospice program [91]. The quality efforts are overseen by a Quality Council, reporting to the Board of Directors.

The committee meets on a monthly basis. There is representation on the committee from the Board of Directors, program leadership, program staff, and an external member. At the meetings, a number of quality items and their indicators are reviewed. Quality items fall into four broad domains: (1) Responsiveness, (2) System competency, (3) Family/Community expectations and goals, and (4) Quality of work life.

Some items, such as hospice census and acuity, are reviewed at each meeting. Other items for example, chart audits or professional development, are reviewed on a semi-annual or annual basis, with a different set reviewed each month. This allows staff to be gathering indicator data targeted towards a specific month's deadline. At the next meeting, the Quality Committee reviews the indicators, which are then forwarded on to the Board of Directors.

Items identified for action are then referred back to appropriate individuals, teams, or committees within the hospice program for further study and action.

Conclusion

Quality initiatives, in all their forms as QA and QI, must now be considered fundamental within health care. Quality efforts have the potential to transform health care delivery organizations by providing them with a framework for evaluating their practices. It is no longer sufficient for health care providers to simply assume that they are doing the right things because they are doing them for the right reasons. Quality efforts, especially QI, provide an opportunity for programs and clinicians to use an evidence-based approach for self-evaluation and standards development.

Quality initiatives, however, are not always easy to implement even in the best of circumstances. They require substantial commitment from leadership, both in philosophy and in

P.591

time and money resources. Undertaking major initiatives without that commitment can leave the organization worse off than before through wasted effort and engendered cynicism. Therefore, the first step in quality efforts is to commit the leadership to the long-term effort and implications of a quality approach. Health care represents a special case for QI, as the outcomes for service organizations are not as easy to measure as those in the commercial world. Palliative care and, even more so, paediatric palliative care present ever-increasing challenges to the researcher and manager who wish to undertake quality initiatives. In addition to the organizational resource challenges, there are issues to be decided regarding outcomes of interest and measurement of those outcomes. These challenges do not, however, exempt paediatric palliative care programs from undertaking quality initiatives. The issues must be addressed head-on regarding the goals of palliative care and the who, what and when to measure questions associated with those goals.