18 - Using medications

Editors: Goldman, Ann; Hain, Richard; Liben, Stephen

Title: Oxford Textbook of Palliative Care for Children, 1st Edition

Copyright 2006 Oxford University Press, 2006 (Chapter 34: Danai Papadatou)

> Table of Contents > Section 2 - Child and family care > 16 - Ritual and religion

function show_scrollbar() {}

16

Ritual and religion

Erica Brown

P.204

Introduction

In the body, a million births and deaths take place at every moment. The body is a miracle of re-birth in which our habits, our likes and dislikes, our hunger, and our states of mind are always driving the body towards change and development. Never for an instant does the body cease to die, cease to be born. We might say that we live through death at every moment.[1]

Birth and death are the two events experienced by all people and religions are concerned with them. Belief in survival beyond death is perhaps the oldest religious conviction of humankind. As long ago as prehistoric times bodies were buried together with tools and ornaments for use in the next life. Today there is a great variety of teaching in world religions about death and afterlife, ranging from belief in the resurrection taught by monotheistic faiths to belief in reincarnation held by the religions of India and beyond.

During the past decade parental bereavement has received considerable attention and a number of descriptive studies have brought to light the unique needs of life-limited children and their families [2, 3, 4]. However, while there is a growing amount of literature available on the psychological needs of families with a life-limited child, scant attention has been paid to cultural care [5].

There is sometimes an assumption that the needs of families from ethnic minority groups are met by resources within their own community [6], but evidence shows that, although they often do not come forward for help, their needs are often unmet, and they struggle with little support [7, 8]. Therefore the need to provide accessible and appropriate palliative care to ethnic minority groups has been recognised as a significant service development issue. A Report from the UK National Council for Hospice and Specialist Palliative Care Services [9] identified, amongst other needs, a need for the provision of culturally sensitive services in relation to the spiritual, language and dietary needs of black and ethnic minority service users.

The chapter is divided into there parts. Part one discusses social, cultural, and ethnic aspects of death and the importance of equal access to care. Part two attempts to define religious needs and describes the findings of small-scale research at Acorns Children's Hospice in Birmingham, UK [10] concerning the experiences and expectations of Asian mothers with a life-limited child. Part three contains information that may act as a springboard for policy and practice in religious care with specific reference to Hindu, Sikh and Muslim families. See Chapter 14 (cross ref after the child's death Ch. 14, Francis Dominica) for additional information, including practices in some other faiths.

Effects of ethnicity/culture on bereavement

Many people have multiple ethnic and cultural identities, possessing mixed heritage with parents, grandparents and great-grandparents from different groups or communities. Ethnicity and culture profoundly affect the ways families experience death, dying, and bereavement. Furthermore, the ways in which a society deals with death, reveals a great deal about that society, especially about the ways in which people are valued.

In pre-industrial societies there were high rates of death at the beginning of life and often children did not enter the social

P.205

world until a naming ceremony took place and the baby became recognized as a member of the community. Indeed babies who died before this time did not receive full funeral rites. Instead of birth and death being viewed as two separate events they were treated as though one cancelled out the other. Perinatal death rates were still high in the United Kingdom as recently as Victorian times. Parents saw about a quarter to a third of their children die before they reached ten years of age.

Today many societies see death as a transition for the person who dies. How people prepare for this transition and how survivors behave after a death has occurred varies a great deal. There are, however, some common themes. Most societies provide social sanction for the outward expression of this in the funeral rites and customs that follow death.

Ethnicity

The term ethnic is often misunderstood and discussion about the meaning of ethnicity has been extensive [11, 12, 13]. For the purposes of this chapter, ethnicity is regarded as referring to a group of people, who share distinctive features, such as shared origin of descent, language, culture, physical appearance, religious affiliation, customs, and values.

Literature about death and ethnicity is limited in both its volume and its scope. Little is currently known about family roles in paediatric palliative care settings within different ethnic groups. There is, however, some literature available giving accounts of death beliefs and funeral rites, focussing on ways of dealing with the body, rather than the experience of death and dying within these groups [14, 15, 16]. A fundamental weakness of the literature has been its insensitivity to the processes of change, which occur as members of minority ethnic communities adapt to their new societies [17]. The view that families from minority ethnic groups look after their own' has rightly been criticised as a stereotyped over simplification. Traditional family structures are changing in Britain as elsewhere in the world, and often relatives may live too far away for them to be present at the time of death. Young Asians who have been brought up in Britain may not have experienced a death in their family until they themselves are adult.

Culture

Numerous definitions of culture abound. In general they tend to place emphasis on culture as a shared system of meaning, which derives from common rituals, values, rules and laws [18]. For the purposes of this chapter culture is defined, as, how people do and view things within the groups to which they belong. Culture also includes a set of shared values, expectations, perceptions, and life-styles based on common history and language, which enable members of a community to function together.

For many people it is important, that they are able to maintain their cultural values and practices, but cultures are not fixed and static. They change in response to new situations and pressures [19].

Some aspects of culture are visible and obvious [20]. These include dress, written and spoken language, rites of passage, architecture and art. The less obvious aspects of culture, consist of the shared norms and values of a group, community, or society. They are often invisible, but nevertheless they define standards of behaviour, how things are organised and ideas about the meaning of such things as illness, life, and death.

Most Western Europeans view physical illness as caused by some combination of bad luck, external factors, heredity and individual behaviour. In other societies, people may consider other possibilities including bad behaviour, divine punishment, jealousy, or another person's ill will.

It is often assumed that a child inherits the culture into which it is born, but cultural awareness is also nurtured through shared rituals, values, rules, and laws. In the words of Unger [21], the word culture is not a noun but a verb.

The culture of the community in which people grow up has a predominant influence on their worldview, and on the way in which they behave. Each culture has its own approaches for dealing with loss although there may be differences concerning spiritual beliefs, rituals, expectations and etiquette. Research indicates that grief is experienced in similar ways across all cultures, but that within cultures there is a huge range of individual responses [22]. Furthermore micro cultures exist within cultures with individual differences.

Throughout the history of humankind, the deaths of babies and children have continued to be common events. Today in countries where the rates of infant mortality are still high, the death of a child may be considered inevitable with mourning lasting little longer than a few days.

In societies where medical and scientific advances have resulted in the decline in infant mortality, childhood death is likely to be perceived as tragic and unfair. Most societies designate the status of bereaved individuals referring to them for example as widows or widowers for those losing a spouse, or as orphans for children losing parents. There are no culturally accepted terms to describe the state of the bereaved parent.

Each culture attributes unique significance to the death of a child. Individual cultures also hold a variety of beliefs about where children come from before they are born, and where they go after they die. Furthermore, the age, gender, family position, and cause of death, may affect the meaning attributed to the death, and determine the rites of passage for grieving behaviour within a given culture.

P.206

Religion

The word religion probably derives from the Latin religare, which means to bind [23]. Faith is the recognition on the part of humankind of an unseen power, worthy of obedience, reverence, and worship. In monotheistic faiths this power is referred to as God , and in polytheistic societies as, the Gods . All religions agree that their deity or the deities have control over the destiny of a person's soul after earthly life is over.

The great world religions have evolved in diverse ways under the influence of the cultures into which they have spread. Some religions provide detailed codes of conduct covering aspects of daily life such as diet, modesty, worship, or personal hygiene. Others have looser frameworks within which people make their own decisions. There are also different groupings within most religions, each of which may have a variety of beliefs, requirements and traditions.

The influence of religion on people's lives varies a great deal. Religion may act as a form of social support, providing companionship, practical help and affirming a person's self esteem through shared values and beliefs. Many people find that their faith is a source of comfort, giving meaning to suffering, and providing hope for the future. However, people may also feel angry, and let down by their God or Gods, and lose their faith. People who do not aspire to belong to a faith may, nevertheless, have strong ethical and moral values and a sustaining spiritual dimension to their lives.

Different generations may hold different views within their own faith, particularly where the second generation has grown up in a different cultural milieu. Children absorb parental attitudes towards religion in the early years of their development without question or analysis. This can influence their thoughts and attitudes in later life.

Sometimes people turn to religion for an explanation of their personal tragedy. Most major faiths teach that physical death is not the end. However the precise form the continued existence takes varies within different religions and sometimes within different denominations. Major themes include:

Belief in the cycle of birth, death and reincarnation;

Judgement that results in reward or punishment for past behaviour and thoughts;

Existing with God in an afterlife in heaven/paradise;

Being reunited with loved ones who have died earlier;

Sleeping or resting until spiritually or physically resurrected by God;

Exclusion from God in purgatory or hell.

Ceremonies and rituals

Much of life is made up of rituals; but these are so much part of everyday activity that people do not necessarily think about their origins or their meanings. The ritual is acted out in such a way that there is instant recognition of the event. Indeed part of the importance of the acting out is that there is little need to explain. Often a variety of non-verbal ways of expressing feelings come into play. Sometimes people create their own ways to give meaning and resonance to what has happened. Others find meaning and comfort in traditional ways of doing things, particularly if they are part of a cultural minority.

The coming together of family, friends at a funeral is a statement of ongoing love and respect even though a person has died. Those who watch what takes place are constantly made aware of the fact, that what is important is not so much what is said, as by what is implied by the coming together. The more ceremony and ritual that is present, the more opportunities there are for the expression of feelings.

Death rites

In virtually all religions there are clearly set out rules, religious laws and procedures about what is to be done during the dying process and after the death. Periods of mourning last for a clearly defined period in many cultures, allowing the bereaved a gradual time to come to terms with what has happened, and to adjust to changes in their lives both psychologically as well as adapt to their changed social status.

The value a culture holds for children and the significance of their death, is reflected in the care and disposal of the body and in funeral rites, which may be quite different from those performed, when an adult dies. In several cultures children are considered innocent and their premature death affords them heavenly status. Thus Puerto Ricans dress their child in white and paint the child's face like an angel. Some Orthodox Christians believe death to be particularly traumatic if it occurs before a young person is married since marriage is viewed as the consummation of earthly happiness. If a young person or a child dies, their body is dressed as if they were wearing wedding clothes and funeral laments are sung, that bear a striking resemblance to wedding songs. In other cultures, such as China, the death of a child is perceived as a bad death and parents and grandparents are not expected to go to the funeral. People avoid talking about the child, because, the event is considered to be shameful. Hence the values, beliefs and practices held by families in Western cultures may clash with those held by families with a different cultural background.

P.207

The ways in which families commemorate their child's life demonstrate and reinforce their beliefs. Individual members may hold differing views about the role of children as participants in funerals and mourning rituals. Some parents may not feel able to discuss their own feelings with members of an older generation who may want to protect children from the pain of death. Hence the attitudes and practices within families may clash.

Religious rituals can also have important spiritual, social, and emotional significance, strengthening bonds between members of a group, giving a shared sense of meaning and purpose. Ceremonies surrounding death often stress forgiveness, preparation for the life to come, transcendence, and hope. Sometimes religious rituals offer a person the chance to participate in religious behaviour without specifying the extent of their belief. They may provide comfort and reassurance to the mourners. The ritual dimension of religion encompasses actions and activities, which worshippers do in the practice of their religion. Activities may range from daily ablutions before prayer to taking part in a once-in-a-lifetime pilgrimage.

Signs and symbols

Symbols may have great significance for families. Religious symbols are inextricably associated with religious belief and observance. Sometimes these are large and displayed in the family home, or they may be small and private, such as pendant or a sacred thread worn by Hindu males, under clothing. Statues or pictures may be used decoratively or as a focal point for private worship.

Natural phenomena such as light and darkness also have powerful significance. The crescent moon and stars appears in Muslim countries, representative of light and guidance for persons on a spiritual journey. Guru , a word with particular significance for Sikhs may be translated as a teacher or enlightener and is derived from the word gu , meaning darkness and ru meaning light. Thus a guru is a spiritual teacher who leads from the darkness of ignorance to enlightenment.

Worship

The basis of most religious observance is worship of a deity (or deities). The form which worship takes, and the expression and location of worship vary between religions, denominations, and individual worshippers.

Worship comprises components such as thanksgiving, praise, and repentance. Expression may be found through prayer, physical position, and movement, reading and reciting sacred scriptures and silence. In some faiths music is very important. For example in Hinduism the sound of a mantra or sacred verse reflects deeper meaning and its repetition acts as a focus to concentrate the mind of the worshipper.

For some people, prayer is an essentially private matter, and it may be silent. For others it may be a corporate activity with family members. Worship at home is important in all faiths. Some religions prescribe set prayers at certain times. Others encourage silent prayer and meditation. In children's hospices where staff endeavours to create a homely environment, it is important that people have private space set aside for worship.

Most religions identify sites of historical and spiritual significance, particularly where the founder of the faith experienced a revelation. Sacred places may include cities such as Makka or Medina for Muslims or Jerusalem for Jews and Christians. Sometimes shrines commemorate miraculous events and appearances and they are the destination of pilgrimages. Muslims for example, aim at least once during their lifetime to complete the Hajj by visiting Makkah, the birthplace of Mohammad.

Children's experience of death

The context of many children's experience of death has changed. In the past, most deaths occurred at home. Death and illness were witnessed first-hand and children were often present at funerals. The ancient nursery rhyme Ring-a-ring o Roses' describes a game played by children during the Great Plague and Black Death of the fourteenth century and seventeenth centuries in Britain. The rosie-ring refers to swelling lymph nodes and a pocket-full of posie to an amulet worn as a protection from the disease. Achoo (which over the years has become ashes in the United States) describes the flu like symptoms associated with the plague and all fall down to the inevitable death of the victims. In the twenty-first century most people die in hospitals or other care settings and death will rarely be within most children's everyday experience.

However, in Great Britain approximately 15,000 children and young people under the age of twenty still die each year. Although Black [24] writes of the remoteness of childhood death in the twentieth century, for some children and their families it will remain a stark reality.

The religious and cultural development of children with life-limited conditions

A child's age, cognitive ability, anxiety level, and home background will all influence their understanding of what happens at the time of death and beyond. Each family is unique, and the culture or faith in which children are brought up, and the way

P.208

in which they are taught at home, and at school will influence the way in which they perceive death. Therefore it is vitally important that life-limited children are given age and developmentally appropriate opportunities to share and explore their fears and concerns. Children often indicate their awareness of serious illness and communicate their beliefs about what happens after they die through drawing and painting. In order that carers are able to work effectively with children it is important that they are aware of what children have been taught by their families and communities.

In the early stages of their development, children are egocentric and their understanding of religion is based on their experience within their family. Some children will have engaged in religious practices; some will have had occasional experience of religion; others none at all. Many may have an awareness of symbolism in religion and they are likely to have heard stories about the lives of key figures and religious leaders. They may also understand that for some people, places, food, and occasions have special importance. At this stage it is important to provide a foundation on which to build children's increasing awareness of themselves as individuals and of their relationships with other people. Helping them to respond to different environments provides a framework for cultural, and religious experiences with which they may be familiar such as reflection or meditation.

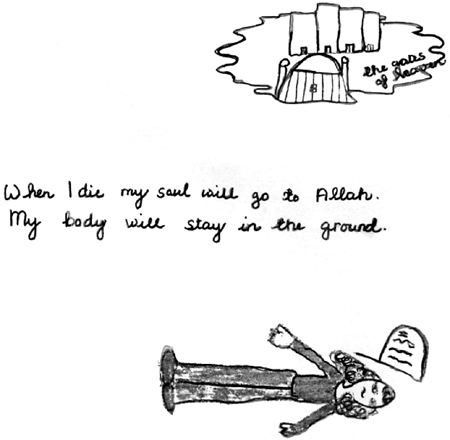

In the middle years, children have a greater understanding of themselves and an awareness of the faiths, and cultures in which they grow up (See Figure 16.1). Some families may choose to talk about death and dying, and perhaps the concept of the soul moving on to another form of life. Children's relationships with members of the local and wider community will have an important influence on their sense of personal identity, and purpose. Many children will have an awareness of the contribution they make to the communities to which

|

Fig.16.1 A 10 year-old Muslim girl shows her understanding of burial and her hope for heaven in the next life. Interestingly, many Muslims would not depict the human body or heaven in pictorial form. |

P.209

|

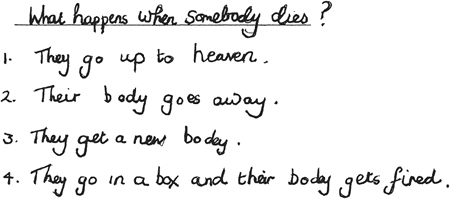

Fig.16.2 An 8 year-old boy asked the question What happens when somebody dies? He then attempted to give his own answers to his question. |

they belong, and there should be opportunities to help them create memories for the people who will grieve after they have died.

Young adults are often fiercely independent and they seem to have an urgent need to get on with living their lives. This may conflict with having a life-limiting illness. There is often an impressive determination on the part of young people to deny the reality of the situation and carers need to respect this. Opportunities to explore the common ground between their own experiences and spiritual and religious questions of meaning and purpose may be helpful. Where young people are members of families with a religious belief their questions are likely to include a spiritual and religious context (See Figure 16.2).

Bluebond-Langner [25] and Brown [26], describe how life-limited children with special educational needs may have a sophisticated understanding of death that includes a religious dimension. Turner and Graffam [27] have worked extensively with young people with learning disabilities and their research has included dreams about death. A consistent theme is the appearance in a dream of a person who has already died. Sometimes the deceased person invites the life-limited young person to join them.

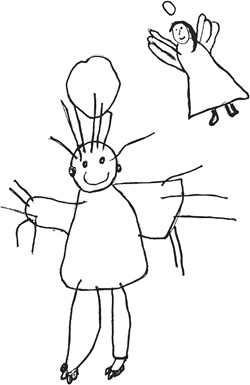

Religious themes often appear in children's thoughts about death and an after-life. Heaven is nearly always regarded as a desirable place where life continues after earthly existence is over although mostly this life is in an altered form such as becoming an angel (See Figure 16.3). For some children hell appears as an alternative destination although young people rarely talk about it as a possibility for themselves.

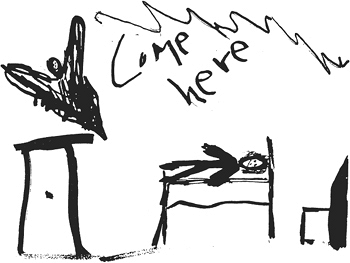

For some children thinking about religion may be unhelpful (See Figure 16.4). The relationship between religion and death-anxiety has been studied by a number of researchers [28, 29]. Where young people are actively involved as worshipping members of a religious community, death-anxiety

|

Fig.16.3 A 5 year-old girl draws herself as a baby angel in heaven accompanied by her mummy, who will be there to look after her. Note the halos. |

P.210

|

Fig.16.4 An 8 year-old boy newly diagnosed with a life-limiting condition has night terrors about being taken by the angel of death when he dies. |

appears to be lower although personality, temperament and life experience all play their part.

Children's questions

Many children are curious about death and their questions about their illness may be accompanied by a fascination about what happens next. Religions seek to give responses to mysteries of human existence. Some children may question their faith, wondering how a just God can allow them to die. Others may turn to religion to find an explanation for what is happening to them. This may involve thoughts about sins they have committed, laws they have broken or faith they have lost. Thus, children's questions probe the world around them as they reflect on their past and present life and strive to make sense of the future.

As children grow through normal developmental stages their questions may change. Young children often ask questions based on their need for reassurance and they are very concerned with adult responses that give them a sense of security and safety. When they are older they are likely to need more detailed replies to questions as they try to satisfy their curiosity, uncertainty, and perplexity. By the time they are of secondary school age young people require more specific information, and their questions may include situations outside the belief and culture of their family. This may present a huge challenge for families and carers who feel ill-equipped to explore the complexity of young people's needs.

Fundamental to working with life-limited children is an ability of adults to understand what individual children really want to know. Some questions point to larger questions to which there may be no definitive answers. Comments such as there is nothing to be frightened about may sell children short. A parent's own fear may also lead to denial of their child's inevitable death. Goodhall [31] emphasizes the importance of telling the truth, answering questions and using easily understood language instead of euphemisms and metaphors.

Children's attempts to answer questions such as, why do I suffer?, or why will I die?, may help them to make sense of what is happening in their own life story. Hitcham [32] writes, Inside every child there is a story waiting to be told but when that story involves difficult issues such as death and dying, it is neither easy to tell nor to listen to'.

Creating personal life-story books can help children to encapsulate their experiences. Some children may keep diaries that are important to them as private documents whilst they are alive. After their death these can provide their families with an insight into their child's journey. Other children may like to create a memory box in which they record their life story through writing, art and collections of symbolic objects.

Caring in practice

When people are ill or vulnerable they need care that is focussed on their needs, and what is important to them. Professionals require the skills, information, and confidence to find out what each family wants and organizational structures, which are sufficiently flexible to enable them to provide it. Practices, beliefs, and attitudes are continually emerging. Professional awareness

P.211

of the range of such patterns can be a vital starting point in addressing the needs of ethnic minority families.

At a time when services are under great pressure and resources are stretched, the demand for holistic family-centred care that takes into account different cultural, religious, and personal needs may seem unrealistic. Holistic care for dying children and their families requires special skills, and sensitivity. Identifying and meeting individual, cultural, and religious needs are important parts of that care.

In order to be effective, members of the caring professions must be aware of their own social mores, prejudices, and worldview. People's attitudes and beliefs profoundly affect the way they respond to other people, particularly those whose lifestyles are different from their own. In 1995, Infield, Gordon, and Harper [33] concluded that while many people are individually knowledgeable and culturally sensitive, few hospices had systematically planned services to meet the needs of culturally diverse groups . Therefore it is not surprising that generally, children's hospices are finding it difficult to attract referrals from minority ethnic groups [34].

Good service can be provided which is appropriate for families from a wide range of cultural and ethnic backgrounds, whether the child is being cared for at home, a children's hospital, or a hospice. Where service providers are committed to meeting the needs of different groups take-up has often been dramatic (Acorns Children's Hospice Trust, unpublished).

The experiences and expectations, of ethnic minorities with a child, with a life-limiting-condition, are under-researched areas of palliative care in children. Acorns Children's Hospice in the UK conducted one small-scale project [10] in 2002 examining the difficulties of Asian mothers. The study identified prejudice in their own faith or cultural communities, and common experiences of patronizing and dismissive approaches by professional groups when raising concerns about their child. This research has led to a number of changes in the way palliative care was delivered both at the hospice itself, and by other local health care providers. There is an Asian liaison officer who has worked with families to help them communicate their own needs actively, both within and outside the family unit. This has also helped families, particularly mothers, to understand options available to them, for example having a place set aside for worship or meditation or appropriate facilities to wash their child after they have died.

Religious and cultural artefacts are made available at Acorns hospices for families to use. Menus provide for a variety of dietary preferences and food is prepared and cooked in an appropriate way. Where possible, care for boys and girls, is given by staff and carers of the same sex.

At the heart of the philosophy of palliative care is holistic care for all families with a life-limited child, irrespective of religious, racial or cultural background. Education and training can raise staff and volunteer awareness of attitudes that can safeguard against stigmatisation and stereotyping of ethnic minority families. At the same time, their needs to be parallel research and development that can provide an evidence base for a model of care that is matched to the individual needs of service users. Good practice in achieving accessible and appropriate palliative care services will only be experienced if the stated policies and practices are in harmony; the children and their families are made to feel welcomed; and their views are listened to and acted upon. Equal access means offering responsive, flexible services to families, in which individual needs are identified and accommodated so that each person benefits. This cannot be achieved by an ad hoc system or by individuals working in isolation. Equality must be supported by the ethos of the organization, be understood and implemented by all managers and employees, and backed up by training and practical support.

Caring for families

Over the last two decades there has been increasing awareness of the importance of listening to the views of parents of life-limited children and planning services which are sensitive to individual family needs. There has also been corresponding concern about the stereotypes which have been created concerning the level and nature of support which families would welcome.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child [35] makes several references to the importance of religious and cultural care. In the United Kingdom families embrace a wide diversity of religious beliefs, or none. Information for practitioners about different faiths and cultures is useful only if it is relevant to the people concerned, comes from reliable sources, is based on a commitment to the view that all faiths and cultures have intrinsic worth, and are equally worthy of respect, and acknowledges the complexity and variety of the real world. Therefore, it is essential that practitioners should have access to accurate information and advice [36].

Of course there is a danger that in attempting to describe and to classify beliefs and practices this leads to one-dimensional snapshots. Hence all guidelines are likely to contain some generalisations and crude stereotyping that ignores variation and idiosyncrasy.

The purpose of this part of the chapter is to introduce some examples of beliefs and observances of particular relevance to the everyday life, care, and well being of children and their families. Particular attention is given to caring for the dying child, and for the child's body after death. Space prohibits detailed or comprehensive information concerning all faiths. Therefore Asian traditions of Islam, Hinduism, and Sikhism have been chosen. In the course of writing, I have

P.212

drawn on the advice and support of a great many people. Some are colleagues kind enough to share their knowledge; others are families who are practising members of a religion or leaders from faith communities.

Islam

The total size of the Muslim community living in the United Kingdom as recorded in the 2001 census is just over one and a half million. Muslims represent 3.1% of the total population of England and Islam is the second largest faith group in the United Kingdom. Although the largest concentration of Muslims is in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, many people live in Birmingham and Bradford. Most of the Muslim community is very young with over half of all persons under the age of 25. There are more males than females.

Muslim families

Families are central to Muslim life and Muslim society. In the Qur'an, Allah gives specific guidance on the rights, responsibilities, and obligations of every Muslim within their own family, and stresses the family's value as a source of support, love and security. In Asian culture the family is traditionally a much larger unit often referred to as the extended family.

Marriage and the raising of children are fundamental to a good Muslim life and are religious duties.

Sons are considered responsible for the care and support of their parents, as they grow older. When a son marries, he and his wife often remain with his parents and bring up their children.

Sexual morality is strict. Sex is only permitted within the context of marriage, in which men have specific and clear responsibilities to protect and provide for women and children. Extra marital relations are forbidden and condemned in the Qur'an. In some communities it is considered responsible to segregate sexes after puberty.

Men and women

Within Muslim families, men and women generally share decisions, with women chiefly responsible for the comfort of the family, and the upbringing and moral education of the children. Outside the home, Muslim women are generally under the guardianship and protection of men: fathers, husbands, or sons if the woman is a widow.

A rigid code of public behaviour is often observed between the sexes. For example, on visits to Muslim families, men and women do not normally shake hands. It is considered courteous for the woman of the family to withdraw or remain silent when men or older people are talking to visitors. Outside the family, men and women usually socialize separately.

Religion

Muslims believe there is one God, Allah, and that Muhammad is his messenger. Allah is the Arabic word for God. God is the Eternal Creator, Compassionate and Merciful. He is All-Knowing and All-Powerful and His will must not be questioned in any way. He alone is to be worshipped.

Muslims believe that Muhammad was the last of a long line of Prophets. The Prophet Muhammad taught that he was a messenger, chosen to proclaim God's will. It is customary for Muslims, when they say the name of the Prophet Muhammad, to add the words Peace be upon him , immediately afterwards. Respect is paid in the same way to other Muslim Prophets.

Muslims have certain religious duties to perform. These include the five pillars of Islam: faith in God, daily prayer, fasting during Ramadan, giving alms (if their means allows) and making a pilgrimage to Makkah.

Islam teaches about life after death and in resurrection from the dead at the Day of Judgement. Every individual should live on earth as perfectly as they can. When a person dies they will be judged by God and rewarded or punished for the life they have lived.

The duties of Islam

The five main duties which Muslim men and women perform are know as the Pillars or Foundations of Islam. Not all Muslims practice every aspect of their faith strictly, but for those who do, the five pillars of Islam are extremely important.

The statement of faith (Shahadah)

All Muslims must make a statement of their faith in God, and in Muhammad as His Prophet.

There is no God but God and Muhammad is the Prophet of God.'

Prayer (Salah)

Most adult Muslims will wish to say set prayers (salah) at five specified times every day. Children are encouraged to say prayers from about the age of seven years. The times of prayer are specified in the Qur'an:

after dawn (Fajr)

around noon (Zuhr)

in the mid afternoon (Asr)

early evening (after sunset) (maghrib)

at night (Isha).

A certain amount of leeway is allowed so that people can pray at convenient times. Local times of prayer are published in the British Muslim newspapers, and by local mosques.

P.213

Before praying, Muslims should wash. When praying he or she should stand on clean ground (a prayer carpet is often used). This should face Makkah (south-east in Britain). Both men and women should remove their shoes and cover their heads before praying. During the prayers certain specified movements must be performed at different stages: standing, kneeling, bowing and touching the ground with the forehead.

Washing in preparation for prayer (Wudu)

For Muslims, physical and spiritual cleanliness are closely linked. It is stated in the Qur'an that every Muslim must always wash parts of the body thoroughly in running water three times before praying. Ritual washing follows a set routine: the face, ears, and forehead, the feet and the ankles, and the hands to the elbows. The nose should be cleaned by sniffing up water and the mouth should be rinsed out. Washing facilities are always provided in mosques.

Many Muslims will also wish to wash after using the toilet and most would not want to pray unless they have done this. People often take water for washing into the toilet with them if a washbasin is not provided in the lavatory cubicle. Women will wish to be particularly scrupulous about hygiene during menstruation.

Exemptions from the five daily prayers

Certain people are exempt from the set prayers although they may still want to say private prayers. This includes women for up to forty days after childbirth and during menstruation. Seriously ill people are exempted altogether but they may still wish to follow the requirements for prayer as far as they are able.

Friday prayers (Jumu'ah)

Friday is the Muslim holy day. Most male Muslims over the age of twelve will wish to go to the mosque for prayer. The precise time of Friday prayer varies depending on the committee of local mosques but it is usually at midday, or early afternoon. Some mosques provide a separate prayer room for women but many will wish to stay at home saying their normal noonday prayers.

Fasting (Sawm)

Healthy Muslims over the age of twelve will usually fast during Ramadan. Ramadan is the ninth month of the Muslim year, and the month in which the Qur'an was first revealed to the Prophet Muhammad.

Muslims consider that fasting enables them to reach a higher spiritual level, and therefore to come closer to God. During Ramadan Muslims will wish to abstain from all food, all liquids (including water), and tobacco between dawn and sunset. They also abstain from sexual relations at these times. The times of beginning and breaking the fast and of the five set daily prayer times during Ramadan are usually published and circulated by local mosques. Many Muslims will get up early during the month of Ramadan and eat a meal before the fast begins.

Exemptions from fasting

All Muslims except young children (under the age of 12 years) are required to fast, but there are certain exemptions:

People who are ill may not fast but they will often make up for the number of days they have missed as soon as possible after Ramadan.

Elderly people or children with special educational needs do not have to fast for the full month but some may abstain from eating if they are able to do so.

Women who are menstruating are not allowed to fast, but they should make up the number of days of fasting they have missed at a later date.

Women who are pregnant or who are breast-feeding are not bound to fast but they should also make up the days missed at a later date. However, some pregnant women may decide to fast, taking the opportunity of making a full and complete fast during Ramadan since they are not menstruating.

People on a journey are not bound to fast but they should also make up the number of days they have missed as soon as possible after Ramadan.

Children are usually encouraged to fast for a few days from about the age of seven onwards. They often fast with their parents on Fridays and at weekends. From about twelve years young people will often fast during the entire month.

Alms giving (Zakah)

Alms giving is an integral part of Islam. The Qur'an requires every Muslim who can afford it to give approximately two and a half per cent of their disposable income every year to needy people or to the upkeep of the mosque.

Pilgrimage (Hajj)

The Qur'an teaches that every Muslim who is able, should make the Hajj, a pilgrimage to Makkah, at least once in their life. The Hajj is made during the second week of the twelfth month of the Islamic year (Dhul-Hijjah). Every pilgrim walks the same route and everyone joins in prayers. In the year 2002 over 3 million Muslims made the Hajj.

Muslims regard going on Hajj as a unique spiritual and emotional experience. The Hajj often has a profound and lasting effect on those who have made it. The pilgrimage takes 6 days.

P.214

The Qur'an

Muslims believe that the Qur'an is the word of Allah revealed through the Prophet Muhammad, and written down without alteration, in the words in which it was revealed. It is God's final statement on the whole meaning, purpose, and conduct of human existence.

Because the Qur'an consists of the actual words of Allah, it is treated with the utmost reverence. It must not be criticised or altered in any way, and its meaning cannot be changed, adapted or re-interpreted to suit people's wishes or values.

The Qur'an is written in Arabic. It is divided into 114 chapters (surahs) of varying lengths. It reveals the nature of God and His relationship with humankind and people's duties on earth. It also lays down detailed practical rules on many aspects of individual, family and community life, though it allows a good deal of leeway to take individual circumstances into account. For example, there is guidance on suitable food, proper dress, prayer, family duties, and responsibilities, borrowing and lending money, alms giving, gambling, alcohol, marriage, divorce, and inheritance. Devout Muslims turn to the Qur'an for guidance on most matters and problems. For areas that are not covered by the Qur'an, the Shari'ah, or Islamic law, gives guidance.

Care of the Qur'an

The Qur'an must be treated with great care. Nothing may be placed on top of it and it must not be touched by anyone who has not washed in the way which is required before prayer. The book is normally kept high on a shelf, wrapped in a cloth. It is placed on a stand when it is being read and should never be put on the floor. A small piece of cloth, leather or metal, containing words from the Qur'an may sometimes be worn as an amulet around a person's arm, the waist or neck. Unless it is unavoidable, other people should not remove this and it should be kept dry.

Learning to read the Qur'an

Most Muslim children go to a mosque school after school on weekdays or during the weekend for religious instruction. At the mosque school young people learn to read the text of the Qur'an in Arabic and memorise parts of it. Most children in the United Kingdom begin to attend mosque school at the age of five; girls attend till puberty, but many boys continue until they are fifteen years old. Most parents feel that it is essential that their children should be well grounded in the religion.

The mosque

In a Muslim country a mosque is primarily a place of worship for men and a centre for religious education for children. In the United Kingdom many mosques provide instruction for children in their mother tongue as well as in reading the Qur'an, and mosques still form an important focus in community life. In many communities women do not attend the mosque for prayer but pray at home. However, older, married women, well educated in the Qur'an and in Islam, may visit other women in the community in their homes to teach and pray with them. Women may attend the mosque for meetings and other functions

The organization of the mosque

Islam has no ordained priesthood. There is no central Islamic authority or hierarchy. Each community has its own religious leaders who are local men with status in the community (Imams).

The Imam

In the United Kingdom the Imam is the senior teacher or spiritual leader in the mosque. He performs all religious functions and teaches in the mosque school. Although it is not part of their traditional role, some Imams do fill pastoral functions.

The building

Each mosque usually contains a room for prayer, washing facilities, a schoolroom and a room for lectures or discussions. In the United Kingdom, some mosques are converted houses, though more and more communities are building new mosques with traditional Islamic architecture. The prayer room is usually very simple. The walls are normally bare but may have Qur'anic inscriptions on them. There are no seats. People stand, sit, or kneel on the carpeted floor. In the middle of the wall closest to Makkah (the south-east wall) there is a niche, (mihrab), towards which all the worshippers face while they pray. On the right of the Mihrab is a raised pulpit or chair (Minbar) from where sermons are delivered.

Before entering a prayer room all Muslims perform ablutions. Shoes must be removed and left outside, and heads must be covered. Both sexes must be modestly dressed.

Clothing

Muslim men and women are required to be modest about their bodies. Many Muslims find any exposure offensive and shocking. Muslims should traditionally be clothed from head to foot, except for the hands and faces, and their clothes should conceal the shape of their bodies. Women from Pakistan and Gujarat will usually wear shalwar kameez. A sari may also be worn on special occasions such as weddings. The kameez (shirt) is a loose tunic with long half sleeves. The shalwar (trousers) are usually cut very full to avoid immodesty. A long

P.215

scarf (chuni or dupatta) is an integral part of the outfit. It is laid over the shoulders and across the chest to cover the breasts. A woman may cover her head with one end of the dupatta when she goes out, or as a sign of respect or modesty, in front of visiting strangers, older people and men. Muslim women from Bangladesh traditionally wear a sari with a waist length blouse and underskirt beneath. One end of the sari may be pulled over the head as a sign of respect or modesty. Muslim girls and women who wear western dress may wear trousers or long skirts to cover their legs. Jewellery may have important religious or cultural significance. For example, a woman may wear a taviz, a small cloth, or leather amulet containing words from the Qur'an. Some women may also wear a small medallion with words from the Qur'an engraved on it.

Traditional Pakistani male dress is a shirt (kameez) and loose trousers (pyjamas). The traditional dress of Bangladeshi men is a shirt and a lungi, a length of cloth wrapped around the waist, usually reaching down to the calfs. Muslim men cover their head, usually with a hat or cap (topi), while praying, and as a sign of respect at ceremonies such as marriages and funerals. Devout Muslim men may wear a hat or cap at all times.

Washing

Most Muslims prefer to take showers rather than baths, since they do not feel clean unless they have washed under running water. Where showers are not provided they may prefer to pour water over their heads. After using the toilet, Muslims wash themselves with water, using their left hand. Because the left hand is traditionally used for washing, the right hand is normally used for eating. Many people observe this custom.

Diet

Muslim food restrictions are clearly laid down in the Qur'an and are regarded as the direct command of God

Muslims may not eat pork, or anything made from pork (sausages, bacon, and ham), or anything containing pork products (e.g. cakes, baked in tins greased with lard, eggs fried in bacon fat, suet puddings).

Other meats or meat products are acceptable provided they are halal or killed according to Islamic law. To be halal the name of Allah must be pronounced over the animal and its throat must be cut so that it bleeds to death. N.B. The opposite of halal is haram, meaning forbidden.

Many Muslims will refuse food if they are not certain of the ingredients. Muslim parents are likely to buy vegetarian baby food for children who are on a semi-liquid diet.

Fish is considered to have died naturally when it was taken out of the water and so the question of a special method of killing does not arise. Except for prawns, all fish, which does not have fins or scales, is forbidden.

Dairy products and eggs are permitted although cheese may be unsuitable if it contains non-halal animal rennet. Cottage, processed, curd and vegetarian cheese, which are not made from animal rennet, may be acceptable.

Alcohol is specifically forbidden in the Qur'an. It may only be used in medicines when there is no possible alternative.

Cooking and serving food

Muslims will not eat food, which has been in contact with prohibited foods. Families may refuse to allow their children to eat foods if it has not been prepared in separate pots and with separate utensils, on the grounds that if pots and utensils have been used for prohibited food they will contaminate all other food they come into contact with. Some Muslims may refuse any food prepared outside their own home, as they cannot be sure that the utensils have always been kept separate.

Birth and childhood ceremonies

Muslims babies are usually bathed immediately after their birth. This is done before the child is handed to the mother. The call to prayer (Adhan) is whispered as soon as possible into the child's right ear and a similar call into the left. This should be done by the father, a male relative or another male Muslim chosen by the family. The words are the first sounds that the child hears and they are important introduction to the Muslim faith.

Shaving the baby's head

The heads of babies are usually shaved as a symbol of removing the uncleanness of birth on the sixth or seventh day after a child is born. Oil and saffron may be rubbed into the child's head.

Naming the baby

The baby may be given its name on the day on which the hair is shaved. The names of siblings and other family members are often chosen.

Marriage

Marriage in Islam is a civil contract rather than a religious ceremony, regarded as a practical and social necessity, and as a landmark in life. Most Muslims would wish to marry. The ideal time for marriage is traditionally shortly after puberty but most countries now have national legislation, which defines the minimum age. Traditionally the families of the young people concerned arrange marriages. Today this practice is changing and young people often play an important part in

P.216

the choice of a partner. Nevertheless, marriage is seen very much as a union between families, not just as a private union between two individuals.

Death and burial

Muslims believe in life after death. The death of a loved one is seen as a temporary separation. Muslims believe that the time of death is pre-determined by God and that suffering and death are part of God's plan. Therefore some people may feel that open expressions of grief and sorrow are sinful because these indicate a lack of acceptance of Allah's will. Some devout Muslims may discipline themselves to show no emotion at all after a death. Others, particularly women, will often express their grief openly.

Care of the dying child

Family members will often sit by a child's bedside and pray and recite verses from the Qur'an in order to give comfort. The family will also repeat the Muslim declaration of faith There is no God but God and Muhammad is His Prophet'. If possible the dying child will sit up or lie with their face turned towards Makkah. A member of the family will usually whisper the call of prayer into the child's ear. If no family members are present any practising Muslim can be asked to give help and religious comfort.

Caring for the child's body after death

Many Muslims are very particular about who touches a dead body. The child's body should not be touched by non-Muslims. It should be treated with love, modesty and respect. Relatives may wish to close the child's eyes, straighten their limbs and turn the child's head towards the right shoulder. This is so that the body can be buried with the face towards Makkah. The body should then be wrapped in a plain sheet without religious emblems. It should not be washed; this is part of the funeral rites to be carried out later on. The child's body is generally taken home or to the mosque and washed three times, usually by the family. In the United Kingdom the family may wash the child's body at the undertakers or at the mortuary. Women will usually wash girls and men will wash boys. (Women are not allowed to do this for forty days after childbirth or during menstruation). Sometimes camphor is put into body orifices. The child's arms are usually placed across their chest. The body is then wrapped in clean white cotton either a seamless shirt, or a white covering sheet. Those who have washed the child's body will wish to carry out their own ablutions.

In Islam, the body is considered to belong to God and therefore, strictly speaking, no part of it should be cut, harmed or donated to anyone else. Post mortem examinations are therefore forbidden unless absolutely necessary for legal reasons. If a post mortem is necessary, the reasons must be clearly explained to families.

Burial

According to Islamic law and practice, Muslims should be buried as soon as possible and generally within twenty-four hours. If this is not possible the child's body may be embalmed. After washing the body, passages from the Qur'an are recited and the family prays. Generally the funeral starts from the family home and the child's coffin may be left open so that relatives and members of the community can pay their last respects. Male members of the family will take the child's body to the mosque or the graveside for further prayers and Qur'anic readings before the burial. In the United Kingdom some Muslim communities allow flowers to be placed on the coffin. Women may go to the mosque or attend final prayers but Islamic law discourages them from going to the cemetery.

Graves should be aligned so that the child's face can be turned sideways towards Makkah. Generally flowers are not sent to Muslim funerals although this may in fact happen in Great Britain. Because it is not always possible to follow the rules for burial laid down in the Qur'an, some Muslim families will prefer to take their child's body back to their homeland. According to Islamic law the area above the grave must be slightly raised, the body must be buried facing Makkah and the grave must be unmarked.

Funerals are often very large.

Mourning

Mourning usually lasts for about a month. During this period relatives and close friends will come and keep the family company and given them comfort. They talk about the child who has died and grieve with the family, sharing the loss with them. The family usually stays indoors for the first three days after the funeral. Friends and relatives usually bring food to the house for them.

For 40 days after the funeral the grave may be visited every Friday and alms given to the poor. On certain days special prayers may be said.

Sikhism

The total size of the United Kingdom Sikh population as recorded in the 2001 census is just over three hundred and thirty thousand. Sikhs represent 0.7% of the population of England. Sikhism is the fourth largest faith group in the United Kingdom and this is believed to be one of the largest populations of Sikhs outside Punjab. The largest community

P.217

in the United Kingdom is in Birmingham, closely followed by the London Borough of Ealing. There are approximately equal numbers of males and females.

Sikh families

Providing for the family and caring for all its members' emotional and spiritual well-being are religious duties for Sikhs. In Asian culture the family is traditionally an extended family, and in the United Kingdom obligations to family members in the Indian sub continent and in East Africa remain very strong.

Sons are considered responsible for the care, and support of their parents, as they grow older. Sikhs are expected to marry, and both men and women are expected to take an active part in bringing up children. There is generally a very strict code of sexual morality.

During his life Guru Nanak worked hard to raise the status of women. Thus men and women are considered equal in Sikh tradition. However, female virtues of modesty are important to Sikh women, and in Asian culture men and women may not mix socially outside the family. Boys and girls are generally segregated from puberty.

Religion

Sikhs believe in one God who is Eternal and the Creator of the Universe. Sikhs stress the need for each person to develop their own individual relationship with God, seeking truth and leading a virtuous life. Each individual must learn about God both from their life experience and through prayer and meditation.

Sikhs strive to become God-centred and less self-centred. Sikhism rejects ritual in the belief that this may prevent individuals from developing a direct and loving personal relationship with God.

Sikhism teaches that each soul may have to pass through many cycles of birth and re-birth through incarnation. The ultimate aim is to reach perfection and so, through God's grace, to become united with God and to avoid re-birth into the world. Re-incarnation is linked with belief in karma, the cycle of reward and punishment for thoughts and deeds. Every individual's present existence is directly determined by their behaviour in their past life, and how they live now will decide the manner in which they return in their next life. However, Sikhs also believe that a person's karma can be changed and improved through the grace of God.

The Sikh Gurus

The founder of Sikhism was Guru Nanak who lived in the fifteenth century. He was born into a Hindu family. Guru Nanak rejected the caste system and idolatry. He taught that one God should be worshipped; that all humankind are equal and that people should devote themselves to good actions and to God. When Guru Nanak died in 1539 his teaching was continued by a succession of nine Gurus, the last of whom was Guru Gobind Singh.

The Five signs of Sikhism and the turban

Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth and last Sikh Guru, gave five signs, known as the Five Ks, by which Sikh men and women could be identified and united. Each of the Five Ks has a symbolic meaning. The turban, traditionally worn by Sikh men, has also become an important symbol of Sikhism.

The Five Ks are:

Kesh or uncut body hair as a symbol of the sacred nature of a person's head.

Kachera or loose underwear (shorts) a symbol of self-discipline.

Kangha, a comb which fastens hair beneath the turban and is a symbol of cleanliness.

Kara, a steel bangle worn on the right wrist which symbolises the unbreakable link with the faith and a visual reminder of commitment.

Kirpan, the sword worn to symbolise the duty to fight against evil and to defend the faith.

Sikhs in the United Kingdom differ a great deal in how far they adhere to wearing the Five Ks.

Kesh: uncut hair and beard

In Asian tradition a person's head is regarded as sacred. Guru Gobind Singh forbade the cutting or shaving on any hair on the body or the head. The long hair (kesh) of the Sikhs is regarded as sacred and should be treated with respect. Most devout Sikh men and women never cut their hair, nor men shave their beards. A Sikh man with long hair wears it fixed in a bun (jura) on top of his head, usually concealed under a turban. His hair and beard will be washed regularly.

Most Sikh women never cut their hair. They usually wear it fixed in a bun or in a single plait. Young women (before marriage) may wear their hair in plaits, or sometimes lose. Older women may cover their hair with a scarf (called a dupatta or a chuni) as a sign of modesty. A few orthodox Sikh women may cover their hair with a tight black (or occasionally white) turban.

Sikh boys with uncut hair usually wear it plaited and tied in a bun (jura) on the top of their head. Very young boys may wear their hair in two coiled plaits pinned to the side of their

P.218

heads. Young Sikh girls usually wear their hair loose or tied back in a plait or ponytail. Many Sikh parents in the United Kingdom decide to cut their children's hair. However, if a child's hair has been kept long it has the same significance as that of an adult and must be treated with the same respect.

Kangha: comb

A man or woman with uncut hair wears it in a bun (jura) kept in place by a kangha, a small wooden or plastic comb. Devout Sikhs who do not wear a turban may carry the kangha in a pocket, or they may wear a miniature kangha on a chain around their necks. A kangha should never be removed without permission.

Kara: steel bangle

Almost all Sikhs wear a steel bangle, or kara, on their right wrist. Left-handed people usually wear the kara on their left wrist. The circular shape is a symbol of unity with God, and of the community of Sikhs. The kara is also a constant and visible reminder to Sikhs that all their actions must be righteous. An adult Sikh should never remove his or her kara. Sikh children usually wear a kara from a very early age, and relatives may give a tiny kara, often gold or silver, to a new born baby.

Kirpan: symbolic sword

The kirpan symbolises a Sikh's readiness to defend their faith. It may vary in length from a small symbolic sword to one metre long. A kirpan is worn under clothes in a cloth sheath (gatra) slung over the right shoulder, and under the left arm at waist level. Left handed people usually wear their kirpan and sheath the other way round.

In the United Kingdom, most Sikhs wear only a small symbolic kirpan or wear a kirpan-shaped brooch or pendant. Some Sikhs may have a kirpan engraved on one side of their kangha (comb). People may wear a full sized kirpan in the gurdwara (temple) on formal religious occasions. Children of very devout Sikhs may wear a miniature kirpan from a very early age.

Kachera: special underwear

Kachera are underwear worn by Sikh men and women. They remind Sikhs of the duties of modesty and sexual morality. The legs of the kachera reached down to a person's knees. Nowadays some people wear ordinary underpants or boxer shorts instead of the traditional style but still regard them with the same importance.

When changing, many Sikhs are careful never to remove their kachera completely. One leg is put into the new pair before the old pair is removed. Kachera may be kept on while showering and the wet pair changed for a dry pair afterwards.

Sacred book

The Sikh Holy Book is called the Guru Granth Sahib. The word Granth means collection or anthology. Before he died, Guru Gobind Singh, the last living Guru, entrusted the Guru Granth Sahib to Sikhs as their Guru (teacher) and guide for the future in the place of human Gurus. The Guru Granth Sahib is now therefore the main religious authority for Sikhs. It is the focal point of the gurdwara and the basis of all Sikh ceremonies. Therefore it is treated with tremendous reverence and love and it is regarded as a unique and wonderful treasure of great beauty. The Guru Granth Sahib is usually consulted for advice at important times such as choosing a baby's name.

The Guru Granth Sahib is written in Punjabi in the Sikh alphabet, Gurmukhi. It is a collection of devotional hymns and poems by six of the Sikh Gurus and by other non-Sikh philosophers. Almost all the hymns and poems were set to music by Guru Arjan Dev who compiled it. Sikhs often learn the Gurumukhi script in order to be able to read and understand the Guru Granth Sahib. In Britain many gurdwaras run evening and weekend classes for Sikh children in their mother tongue to enable them to read the Guru Granth Sahib and to join in worship.

In the gurdwara the Guru Granth Sahib occupies the most important place and it is always the focal point for the congregation. It is placed on cushions on a decorated raised dais (manji) with a canopy over it. At night it is usually removed and kept in a safe place covered with a decorated cloth. A chauri is waved over the holy book by one of the congregation all the time it is open as a sign of respect. Any one entering the gurdwara bows in front of the Guru Granth Sahib before sitting down.

Physical and spiritual cleanliness are closely linked in Sikhism. Therefore everybody must wash before reading the Guru Granth Sahib. Washing facilities are always provided in a gurdwara.

Reciting hymns from the Guru Granth Sahib to music makes up the main part of Sikh congregational worship. Major festivals and events are often celebrated with an akhand path, a non-stop recitation of the Guru Granth Sahib, lasting about forty eight hours.

A few families may have a complete copy of the Guru Granth Sahib in their homes with a special room set aside where it can be treated with the same reverence as in the gurdwara. Many Sikhs also have their own prayer books ( gutka ) containing selections from the Guru Granth Sahib. Prayer books are kept carefully and may be wrapped in a small clean cloth, often of silk, or kept in a case for protection.

P.219

The Gurdwara

Sikhism is essentially a community-based religion. Congregational worship at the gurdwara (temple) is very important. Ceremonies such as engagements, weddings, name giving, and funerals also take place here.

Each gurdwara contains a prayer room (in which the Guru Granth Sahib is kept), facilities for washing, a kitchen, and a communal eating area for shared meals, and usually a small library. In the United Kingdom there are often rooms for children attending classes. The prayer room is generally bare with no seats. The congregation sits on the carpeted floor. There may be pictures of the Sikh Gurus on the walls. The focus of the room is a platform ( manji ) on which the Guru Granth Sahib is placed during the day. Outside the gurdwara a yellow flag flies with the symbol of Sikhism printed on it. People arriving at the building may touch the flagstaff and bow as a sign of reverence.

Before going into the gurdwara people remove their shoes and cover their heads. Men or boys who do not wear a turban cover their heads with a hat or a handkerchief. Some people will wash their hands and feet. On entering the temple each person walks to the dais on which the Guru Granth Sahib is placed and bows low, touching the ground with his or her forehead. Some people give an offering of money or food for the kitchen (langar) and for poor people. By tradition men and women usually sit separately. When visiting a gurdwara, tobacco or cigarettes must be left outside.

Sikh families in the United Kingdom attend services at the gurdwara for several hours every Sunday and on special occasions. Some Sikhs, especially women go to the gurdwara on other days. There is no fixed day for Sikh worship but in the United Kingdom, Sikhs generally hold their main services on Sundays.

Congregational worship ( diwan') usually consists of reading and singing hymns from the Guru Granth Sahib accompanied by musicians ( ragi ) playing drums and a harmonium. The singing of hymns is interspersed with sermons. The service always ends with set hymns and prayers. At the conclusion of worship the congregation are given a small portion of karah parshad , a specially prepared and blessed cooked sweet made of equal quantities of semolina or flour, sugar, and ghee, mixed while prayers are said. This is received with cupped hands. The sharing of karah parshad emphasises the equality and fellowship of all Sikhs.

As part of the gurdwara there is also a communal kitchen ( langar ) where food donated by worshippers is prepared by members of the congregation for everybody present to eat together. Hymns are sung and prayers are chanted while volunteers prepare the food. The meal is usually simple, and consists, for example, of a vegetable curry, yoghurt, chapatti and a dessert. It is always vegetarian. Visitors are welcome to share the food. Cooking and sharing a communal meal stresses the equality of all Sikhs and the rejection of the caste system.

There is no ordained priesthood or religious hierarchy in Sikhism. Any initiated Sikh can lead prayers and read the Guru Granth Sahib in the gurdwara. Most gurdwaras in the United Kingdom employ a granthi as a permanent caretaker and reader.

The gurdwara is supported by donations from the Sikh community. Money is also given to the gurdwara on special occasions such as weddings.

Prayer

Most Sikhs pray privately at home. Many devout Sikhs rise early to pray and recite hymns from the Guru Granth Sahib. A shower is taken beforehand. Short family prayers may also be said in the evening with readings from the Guru Granth Sahib. Further prayers may also be recited before going to bed.

A few Sikhs use a mala or string of prayer beads to help as an aid to prayer. Devout Sikhs may carry a mala'or gutka (prayer book) with them and these should be treated with respect.

Clothing

Many Sikh women will wish to cover their legs and upper arms. The most common form of dress is the salwar kameez. The kameez (shirt) is a long tunic with long sleeves. The salwar are trousers. The width of the salwar legs vary according to fashion, particularly among younger women. A long scarf called a chuni or dupatta may also be worn over the shoulders and across the breasts. Women may pull one end of the dupatta over their head as a sign of respect and modesty in front of strangers, older people or men.

Most Sikh men are very conservative in their dress. Nudity, even in the presence of other men, may be regarded as extremely offensive. Many men wear western style shirts and trousers but some may wear traditional dress to relax at home. Traditional dress is a shirt or kameez and loose trousers or pyjamas. Older men may wear their pyjamas and a shirt with a high collar with buttons down the front. This is called a kurta.

Personal hygiene

Most Asian meals are eaten with the fingers. People who eat with their fingers will wish to wash their hands before and after a meal. The left hand is traditionally restricted to washing private parts after using the lavatory. The right hand is therefore used for eating or handing things. When handing

P.220

something to a Sikh it is considered courteous to do so using the right hand.

Some Sikh women, particularly older women, may consider that they are unclean during menstruation or for forty days after giving birth. At the end of the period of uncleanness they will normally take a ritual shower and clean themselves, their clothes and their surroundings thoroughly.

Diet

For Sikhs dietary restrictions are a matter of conscience and religious belief. Although, as a group, Sikhs are generally less strict than Hindus or Muslims in adhering to dietary restrictions, the dietary practices of each individual is still binding.

The only explicit Sikh prohibition regarding food is against eating meat. Many Sikhs are strict vegetarians, abstaining from eating anything considered as a source of life. Since a strict vegetarian Sikh cannot eat meat, fish, eggs or meat products, any dish containing non-vegetarian ingredients is prohibited, for example puddings containing suet, or cakes cooked in tins greased with lard or containing eggs. Many Sikhs would not wish to eat food that has been in contact with prohibited foods, for example, a salad from which a slice of ham has been removed since it has already been contaminated; or utensils that have not been washed since they last touched prohibited food, are not acceptable.

Non-vegetarian Sikhs generally abstain from eating beef, since the cow is regarded as sacred and is protected in India. Some people will not eat pork since the pig is a scavenging animal in most tropical countries.

In the United Kingdom, Sikhs have often become less strict about what they eat, and many men and children and young people eat chicken, lamb, fish and eggs. Sikh women tend to be more conservative about their food.

Alcohol is forbidden in Sikhism. However some less devout Sikh men drink, but this will be disapproved of by conservative and orthodox members of the faith.

Birth and childhood ceremonies

Ceremonies vary a great deal between different Sikh families and communities. At birth there is no religious ceremony for a Sikh baby. However, some Sikh parents may wish to know the exact time of their child's birth in order to prepare an astrological chart. This might be referred to in later life, for example, when a marriage is being arranged. About forty days after a child's birth, parents usually take the baby to the gurdwara with the family to pray, to give thanks and to perform a naming ceremony. The congregation says prayers.

To choose the baby's name the Guru Granth Sahib is opened at random and the first letter of the first word of the first complete paragraph on the left hand side of the page is read out. A name is then chosen for the baby to begin with that letter. The name is often selected by an older member of the family and is announced to the congregation. Some families may hold an akhand path , or non-stop reading of the Guru Granth Sahib, to celebrate the birth of their baby.

Marriage

Marriage is a sacrament as well as a highly valued social ceremony. The families of the young people concerned usually arrange marriages although this practice is being modified both in the Indian sub continent, and in the United Kingdom. Therefore, young people often play an increasingly important part in the choice of their partner. Nevertheless, marriage is seen very much as a union between two families.

Most Sikh communities give female dowries, although this is not strictly speaking part of Sikhism. In the United Kingdom, Sikh weddings usually take place in the gurdwara or occasionally in a hall or at home. During the short ceremony there are hymns and prayers and the bride and groom walk four times around the Guru Granth Sahib while the whole congregation sings a wedding hymn. At the end of the service the whole congregation receives karah parshad . The bride traditionally wears a red and gold sari or salwar kameez and the groom's turban is usually yellow, orange or red. A wedding reception follows the ceremony. The bride's family usually pays for the wedding.

Marriage is regarded by Sikhs as an indissoluble sacrament. Although divorce has been permitted in Indian law since 1955 many Sikhs still regard divorce as shameful. There may be stigma attached to divorced people, particularly women. A woman who seeks a divorce may risk social disapproval and rejection by her community.

Death and cremation

In Sikhism references to death are often found associated with birth and the words janum'(birth) and maran (death) generally occur together. According to Sikh belief humankind is not born sinful but in the grace of God.

Sikhism teaches that the Day of Judgement will come to every person immediately after his or her death. It also teaches that heaven and hell are not locations but that they are symbolically represented by joy or sorrow, bliss and agony, light and darkness. Hell is seen as a corrective experience, in which people suffer in continuous cycles of birth and death.

In Sikhism there are two distinct doctrines about re-birth. Firstly, the soul passes from one life to another in spiritual progress. Nadar , or grace, is eventually achieved through reincarnation. Secondly, re-birth in animal life is a punishment.

P.221

Care for the dying child

When a child is dying, friends and relatives usually read the sukhmani sahib (Song of Peace) to console themselves. Some families will prefer people outside their community to refrain from comforting them. When death occurs, those present exclaim Waheguru! (Wonderful Lord!), but loud lamentations are not appropriate.

Care for the child's body after death

The child's body is washed and dressed by members of the family or the religious community, and covered with a white sheet. Many parents would wish their child to wear the five Ks, including a turban for a young man. The body is usually taken home for friends and relatives to pay their last respects before the funeral. Gifts of dried fruit, clothes, or money may be put into the coffin. Often the coffin is kept open so that family and members of the community can pay their respects. In some communities flowers will be placed on the child's coffin for the journey to the crematorium.

Cremation