7 - Children s views of death

Editors: Goldman, Ann; Hain, Richard; Liben, Stephen

Title: Oxford Textbook of Palliative Care for Children, 1st Edition

Copyright 2006 Oxford University Press, 2006 (Chapter 34: Danai Papadatou)

> Table of Contents > Section 2 - Child and family care > 6 - The spiritual life

6

The spiritual life

OSB Brother Francis

Introduction

There are only three great puzzles in the world: the puzzle of love, the puzzle of death and, between each of these and part of both of them, the puzzle of God. God is the greatest puzzle [1].

The spiritual life of anyone is an enigma and this is even more so when it comes to children. It will be very different from one person to the next, from one child to the next and from members of one family to the next. However, for all of us, there are common threads. Spirituality is universal, while at the same time, intensely personal and subjective by its very nature.

In paediatric palliative care we come up against the great puzzles mentioned above, every day of our working lives. Sometimes we are expected to know the answers, but in reality we all spend most of our lives trying to work them out. God is, as Williams suggests, perhaps the greatest puzzle of all time and particularly hard for us to make sense of when faced with the care of a dying child and his or her family. When faced with a family whose child or children are dying, or a child coping with an intractable pain or what could be called Soul Pain , we are forced to confront the puzzle of God and may feel:

The chill of loss, the draughty air as if the walls of your soul have been knocked down in the night, and you wake to realise that you are living in a vast exposed emptiness [1]

And when a child, for whom you have been caring over several years dies:

you start to wonder if God was ever there at all, or if the puzzle itself was your own invention to excuse the existence of the random and the brutal where they criss-crossed your life[1]

This chapter sets out to define and explore the experience of soul pain in dying children and their families, and complements the study of the scientific aspects of pain. Soul pain is a distinct condition and there is a risk that a child's soul pain may not be properly addressed if this is seen as just the work of the Chaplain.

Spirituality in the context of this chapter refers to the inner life of the child or adolescent as the cradle for a construction of meaning [2]. The chapter will outline some of the diverse views on spirituality, and look at the psychological factors that influence pain in children. It will start to explore the importance of understanding the role of suffering in children's pain, looking at the spiritual needs of children and families and, through a case history, how we as health care professionals may help with this aspect of their care.

The chapter can only be a whistle-stop tour of the territory of the spiritual care of the dying child and the family. It is a territory that has no reliable map; all we have is other people's accounts, their stories and their own experiences of this painful and hard journey.

Spirituality

Spirituality and spiritual care are the proper concern of all who work with dying children and their families. We must recognise that spirituality and religion are very important to a number of people. However, they are two different aspects of care; spirituality is what gives a person's life meaning, how he views, the world he finds, himself in, and this may or may not include a God or religious conviction. Religious care relates more to the practical expression of spirituality through a framework of beliefs, often pursued through rituals and receiving of sacraments.

Nothing in life is black or white, but a thousand shades of grey, and that is the problem in trying to define spirituality in a meaningful way. All people have a spiritual dimension, but not everyone expresses that dimension through formal or traditional religious language or practices. Therefore, all people will have spiritual needs, but trying to define spirituality in a way that is acceptable to everyone is difficult, as it will be different for each and every one of us. For instance, it has been suggested that Spirituality may be expressed intra-personally, as connectedness with oneself; inter-personally, as relationships

P.75

with others and the environment, and trans-personally, in terms of relatedness with the unseen, or greater power' [3].

The literature suggests a sacred core that consists of feelings, thoughts, experiences, and behaviours that arise out of a search for the sacred in our lives, and is an ongoing dynamic process [4, 5].

Spirituality and spiritual care should be found at the core of good paediatric palliative care, but because spirituality, especially in children, can be difficult to understand, we sometimes use the need to tackle the practical needs in palliative care as an easy escape route from spiritual exploration. This way, we can be seen by the family to be making a difference , and we ourselves can see that we made a difference. However, if we shy away from spiritual care we run the risk of missing something profoundly important to the child and family.

Symptom control follows a relatively clear and well-defined pathway of thought and actions, looking something like this:

analysis,

problem identification,

choice of a solution,

an outcome and followed by,

review.

In contrast, this is not the case when it comes to either identifying or addressing spiritual issues in a child's care, as it:

defies logical analysis,

is difficult to define the problem, and,

often has no measurable solution.

At a much deeper level it also demands more of us as health care professionals.

Spiritual care is about responding to the uniqueness of the child in front of you. The spiritual questions are perhaps the most important questions that we hear or that are ever asked. Companionship is at the heart of real spiritual support; a person needing it wants the presence of a person, not a theological theory.

Little is really known about children's spirituality: what goes on in their minds and how they express it. We can only know these things by asking the individual child and family. We need to give them the respect they deserve at this time and phase of their journey. We need to allow them the honour of expressing what they think, by just asking them.

It has been suggested that the problem in coming to terms with children's spirituality is not in determining whether or not children are spiritual, but whether they have a chance to develop and express their spirituality. Many authors have suggested that children, far from being less spiritual than their adult counterparts, are already equipped for their spiritual journey by virtue of a higher level of openness to an awareness of spiritual realities [3, 4, 5, 6, 7].

The question is not at what age or developmental level children can understand spiritual concepts, but how the child, at his age and developmental level of understanding, expresses his or her spirituality [8].

Coles, after 30 years of working with and writing about children in different settings, suggests that children possess a great spiritual curiosity , and seek both God and the meaning of life. A limitation is that his work dealt mainly with physically well children and not dying children. Even so, he makes the very important point that:

The spiritual needs of children are no different from the spiritual needs of older people. But the expression of their spirituality may be different. The child's house has many mansions including a spiritual life that grows, changes, responds constantly to the other lives that, in their sum, make up the individual we call by a name and know by a story that is all his, all hers [9].

If we are to address the spiritual needs of dying children and their families, we must first come to terms with our own spirituality [10, 11]. As Somers [10] suggests, we need to ask ourselves what our own assumptions about spirituality and maybe even religion are. How do we see spirituality in our own lives and the psychological influence it has on us?

As Sommer aptly says:

To understand how another person is limited, we must understand our own limitations. To enter into another person's pain, we must identify that pain in ourselves. To help another face death, we must be able to imagine our own death. [10]

Spiritual care needs to be seen in the context of relationship with the child and his or her family. It is about being present to them and about accompaniment on their journey as they travel the road and encounter the puzzle of God [12]. There is no one model or book we can turn to for help when it comes to the spiritual care of the dying child. This is because each child is unique, and there is no room for rigidity or inflexibility when it comes to offering spiritual care. We need to be open, spontaneous and intimate, and to hold in mind that children have a high level of openness and awareness for all things spiritual. Our task is to keep the channels of communication open and unblock them if they are blocked.

There are no ready answers to the questions about children's spirituality and what we might say to a child who asks Why am I sick?'or even Why does God hate me? ; or to a parent when we are asked Why my child? or Why our family? No book can give the answers to these profound questions that we, the families we work with, or the child we hold in our arms now seek. It has been suggested that spirituality originates in the heart and therefore, spiritual care comes from the heart after the head has done its homework [25]. Children ask questions from the heart

P.76

(soul); questions that come from the child's heart can only be met with answers that come from the adult's heart (soul).

Spirituality is about how we view the world and how we react within it. In talking about spirituality we need to bear in mind that we all come from different social contexts, that we each have a past, and some have a future. We all have our own form of spirituality. Some may have a religious faith or background, while others may not, and it is out of this setting that our spirituality will manifest itself. It is from this background or setting that the questions and work will come. It is worth noting that before religion was a theology, it was an experience! Spirituality is not restricted to those who belong to a religious denomination. Spirituality can do without religion, but the opposite is not true [25].

Spirituality is central to the care of dying children and their families. If we fail to address these issues, we do the children and families we work with a great disservice.

Children's understanding of death

An important baseline when working with children is knowledge of children's understanding of illness and the concept of death. This is also useful when working with parents, to help them understand just what their child might be thinking and what information they may need [15]. It is very easy for adults to underestimate a child's understanding, and this can be to the detriment of the child and his or her care. Goldman and Christie [13] found that only 19% of families of children dying from malignant diseases mutually acknowledged what was going on. It was felt that 23% of children knew what was happening, but chose not to discuss it. Staff involved in the study tended to overestimate how often discussions took place about the impending death of the child.

Bluebond-Langner [14] demonstrated that children very rarely talk openly about what is happening to them, because of taboos deriving from parents or carers. If they do talk, it tends to be in highly symbolic ways. She also states that the child:

goes through what can often be a long and painful process to discover what it all means. In this process he assimilates, integrates, and synthesises a great deal of information from a variety of sources. With his arrival at each new stage comes a greater understanding of the disease and its prognosis. This leaves him with a great deal to cope with, and it is part of his anticipatory grief process [14].

The above quotation brings together some of the aspects from this and previous chapters to illustrate soul pain in a child. There is a sense of an inner journey the child has to make to find meaning, and this can be a painful process.

Substantial literature is now available on how and when children develop their concepts of death (see also Chapter 7, Children's view of death, Bluebond-Langner). Most of the literature derives from work originally done by Anthony [16] in pre-war London in the late 1930's, and by Nagy [17] in Budapest in the 1940's. These studies have since been replicated, enriched and refashioned as new insights have come to the fore, and as society has changed and developed Bowlby [18], Koocher [19], Swain [20], Bluebond-Langner [21], Kane [22], Lansdown and Benjamin [23], and Clunies-Ross and Lansdown [24].

Most of these studies were undertaken with healthy children. Fewer studies have been done with sick children, or with children living with a life-threatening illness. Clunies-Ross and Lansdown [24] 1988, however, repeated an early study of healthy children carried out by Lansdown and Benjamin [23] in 1985, but this time examined children with leukaemia. This study was very small, involving only 21 children, but no significant differences were found between the two studies.

Lansdown and Benjamin [23] found that out of 105 children aged between 5 and 9 years the following had a complete or almost complete understanding of a concept of death:

60% of 5-year-olds

70% of 6-year-olds

66% of 7-year-olds

nearly 100% of 8 9 year olds.

They also found that children who were verbally competent would be able to discuss death in a way that was surprising for their respective age group. Kane [22] identified a number of components of a developing concept of death:

|

She found that if children under 6 had experiences with death of a relative, this would hasten their understanding of death. However, this was not the case in children over 6.

The journey to the centre

I will take the ring, he said, though I do not know the way [26].

The story The Lord of The Rings offers a helpful metaphor. Here we have a group of people on a journey, a journey that

P.77

covers some very difficult territory and one that has no map. It is a journey that they seem to have very little choice about making, and as much as they would have liked not to make the journey, they find themselves on it. The same can be said for the children we care for, their families and those who work with them.

To help the fellowship in the story make their journey, they have been given a guide and companion. He cannot make the journey for them, but can travel with them, offering support and advice from his past journeys. In many ways this story reflects the interior landscape of the children we care for, our own journey, and the territory of the journey that we will cover together.

For our part it is worth remembering what happened in the story at the council of Elrond:

No one answered. The noon-bell rang. Still no one spoke. Frodo glanced at all the faces, but they were not turned to him. All the Council sat with downcast eyes, as if in deep thought. A great dread fell on him, as if he was awaiting the pronouncement of some doom that he had long foreseen and vainly hoped might after all never be spoken. An overwhelming longing to rest and remain at peace by Bilbo's side in Rivendell filled all his heart. At last with an effort he spoke, and wondered to hear his own words, as if some other will was using his small voice. I will take the Ring, he said, though I do not know the way [26].

We have to take the ring even though we don't know the way or where it will lead us.

Tolkein was a profound believer, a devout Christian who knew that the battlefield is the human soul and that storytelling and the imagination were ways into that world. He was a man who took us on an inner journey even when we thought we were exploring the fantasy landscape of his Middle Earth . It is in this land of the imagination that we can make a connection to the children we work with. It is a land of adventure and story-telling.

We can continue the metaphor of a journey. The journey is to the centre, to the heart of the matter (or, as in the Lord of the Rings to the mountain of fire in Mordor ). On this journey, we have to engage with the children and families and travel through several stages of trust with them, if we are to get to the heart of the matter . They need to know that we are truly listening to what they are saying and that we are also listening out for what they are not saying: Every illness has two diagnoses, one scientific and the other spiritual, which involves meaning and purpose [27].

To identify both these diagnoses we need to bring wide angle lenses to palliative care, otherwise we may not be able to grasp or see what is being suggested in this chapter, or indeed, by the children we work with. We need to expand our thinking from our purely scientific and practical minds, and try to see with our inner eye and listen with our inner ear.

Dying children and their families find themselves on a journey, a journey that they have had very little choice about making, and as much as they would have liked not to make the journey, they now find themselves making it.

Spirituality is about making a journey , and that journey is to the centre, to the heart of the matter, to our deep centre , where sometimes we meet our pain, and have to name it.

All sick children will at some time think about what is going on not only in their bodies, but also in their inner worlds [21]. On this journey they need us to be alongside them. They need us to be both their companion and their advocate. Knowing that, the most we can do is to prepare and hold the space where they can start to do the work they need to do for the next stage of their journey, where they can explore their inner-world and where the miraculous may happen.

We need to try and create a safe and secure or sacred space , where the child and family can express their inner-world and suffering and know that it is all right to do so, that they will be heard and taken seriously. We can help them best by sitting with them, watching with them, waiting with them and just wondering what may happen next. We can take our lead from them, go with them, try not to direct them, and try to use the language and imagery they present to us.

Sir Luke Fildes depicts this attitude well in his painting The Doctor . (cross reference to this illustration is also being used by Sandra Bertman in Chapter 5). It depicts the doctor, the child and the quality of the relationship between the two of them. The doctor is attending to the child, watching, waiting and wondering. He is there, which is by far the most important thing he can do. However, we must not forget the parents waiting in the shadows of this powerful painting.

Spiritual care is about responding to the uniqueness of the child in front of you and accepting their range of doubts, beliefs and values just as they are. It means responding to their spoken or unspoken statements from the very core of that child as valid expressions of where they are and who they are. It is to be their friend, companion, and their advocate in their search for identity on their journey and in the particular situation in which they now find themselves. It is to respond without being prescriptive, judgmental, or dogmatic, and without preconditions, acknowledging that the child and other members of the family will be at different stages on that very personal spiritual journey [28].

On this journey we are the invited guest , we will join them for a part of the journey as a guest and accordingly we should behave like a guest. Sometimes we just want to fix things but we may need to acknowledge that we can't, though we may be able to help. The beginning of wisdom is being able to say, I don't know .

We need to be able to be open to the children teaching us. We need to be prepared to learn from them. It seems that the trick here, as in other aspects of paediatric palliative care, is that we need to be able to understand or crack the child's code. We can start to do this if we just sit with them, if we learn to watch, wait and wonder with them. We can take our lead from them and be responsive to their needs, and not the needs we think they may have or our own needs at this time.

P.78

Concepts of soul pain

In this chapter when the word soul is used, it is implied that it is that which we sense to be:

the essential part of each of us ,

the soul is the world within ,

the world we ignore at our peril .

Soul pain holds the key to the child's world. For me it is a reality in clinical practice. It is on my check-list , when I am assessing a child or his or her family who are in pain . This approach is born out of many years of clinical experience of working with children who are either life-threatened or life-limited. I hope that by the end of this chapter, soul pain will be on your check-list of things to look out for, when you are faced with a child or family with intractable pain .

Definitions of soul, psyche, and spirit

In modern Christian culture, the soul is that uniqueness and passion within each human being and the soul is thought to be that part of human beings which gives their lives meaning and essence, conferring individuality and humanity on them.

Our soul has two main functions. First, it must put some fire in our veins, keep us energised, vibrant, living with zest, and full of hope as we sense that life is ultimately worth living. Secondly, it has to keep us together. It has to give us that sense of who we are, where we came from, and where we are going. It is also that part of us that holds memory for us.

One of the hardest words, or concepts, to define is that of soul . Definitions again will depend on the cultural, religious and psychological influences on an individual; the way each person views himself and the world. Some would even say that the concepts of soul and psyche are the same. However, Hillman [29] suggests that people incorrectly use the term psyche and soul synonymously: The terms psyche and soul can be used interchangeably, although there is a tendency to escape the ambiguity of the word soul by recourse to the more biological, more modern psyche. Psyche is used more as a natural concomitant to physical life, perhaps reducible to it. Soul , on the other hand, has metaphysical and romantic overtones'.

For Hillman the two are quite different. He suggests that The spirit has to do with an upward movement [transcendence], and the soul relates to a downward movement [depth]' [30].

Spirit is about transcendence and soul is about depth. He saw the spirit as the phoenix rising from the ashes. The soul being the ashes from which the phoenix arose.

Or, as Moore [31] has eloquently put it:

Soul is not a thing, but a quality or a dimension of experiencing life and ourselves. It has to do with depth, value, relatedness, heart, and personal substance. I do not use the word here as an object of religious belief or as something to do with immortality.

The key words in this definition are depth , value , relatedness , and personal substance . It is these words that mark some of the differences between soul and spiritual pain. It is in these words that we will begin to find some of our symtomatology of soul pain .

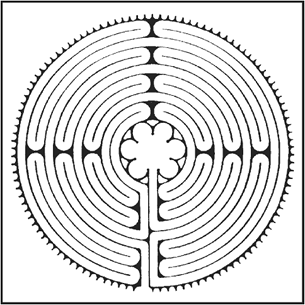

Soul pain can be likened to walking through a labyrinth. We think we are getting closer to the heart of the matter, and then we turn a corner and find that we are even further from the centre. However, we need to remember that a labyrinth, unlike a maze, has a single path that, eventually, takes us to the centre and is not designed to make us lose the way, but paradoxically, to find it.

The Labyrinth (Figure 6.1) is symbolic of our life's journey and that journey is towards the center, our deep centre , where sometimes we meet our pain, and have to name it.

This in turn relates to what hospice is all about. The concept of hospice comes from a monastic background. A hospice was a place run by monks, for sick and tired pilgrims. They were on a journey, like the families we work with and they too can be seen as coming to us for rest and refreshment on their pilgrimage. They have invited us in, to join them on this part of their journey. We are invited guests Christians walked the labyrinth when they could not make the pilgrimage to the Holy Land.

There is a difference between the concept of soul pain and what is often referred to in the literature as spiritual distress

|

Fig.6.1 The Labyrinth from Chartres Cathedral in France. |

P.79

or spiritual pain . The children and families with whom we work demonstrate this difference and the work is clearly soul work , as Freud would have called it. I believe that the fundamental difference between the two is that of direction [32]. Spiritual distress may well be one of the symptoms of a child's soul pain, but it could also be a distinct condition needing its own definition.

Both soul and pain have a subjective quality about them that eludes precise definition or even assessment in the scientific sense. It may be that they can only be depicted.

Pain

The experience of pain is very difficult to define, as it will be different for each and every one of us.

Pain is a paradox. It is replete with anomalies and contradictions. It can be creative and destructive; it can ennoble and embitter; it can protect and destroy. Pain can be a warning sign that something is wrong, and yet can diminish the will to live. It can be associated with survival and also with disease and death [33].

We do not doubt the need to be very focused in our work when trying to assess and manage a child's pain, distress or suffering. But sometimes, especially for a child or a family who have an intractable pain , we need to expand our focus. We need to take a wider view than the purely scientific, and think more about the experience of the pain for the child and the family.

Patients with intractable pain highlight the complex interaction between pain and suffering, and force us to recognise our medical and psychological limitations [34].

Pain is subjective and has been described as:

an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage. International Association for the Study of Pain: Pain [35].

It is important to recognise that pain, including children's pain, cannot be predicted solely by the nature of tissue damage. We know and understand that:

The degree of tissue damage is only one factor among many that contribute to the perception of a painful experience [36].

Now we talk about what Dame Cicely Saunders has called Total Pain [37] or what we might call total or persistent suffering. The word pain implies: That which causes the individual to suffer, be it physically, psychologically, spiritually or emotionally.

The cure of physical pain may be analgesia, but the cure for spiritual (soul) pain is to be found in the experience of the pain itself. Spiritual (soul) pain, then, is not so much a problem to be solved , as a question to be lived , and thus demands different qualities in health care professionals [38].

The question at this point may be: is it physical pain or is it emotional distress? Regnard and colleagues [39] have looked at identifying pain and distress in adults with profound communication difficulties, and conclude that there is no difference between some of the signs of pain and distress. This work could be applicable to the children we work with. The similarities they found in physical expressions of pain and distress, for example, facial expression and behaviour, make the assessment process very difficult, so we need to keep an open mind as to what we are seeing, and make more enquiries. When trying to assess a child with either profound communication difficulties or poor communication abilities, or even a child with good communication skills, albeit distressed, Regnard suggests we can look to his eyes for some clues to the degree of this distress. Eye contact is usually made when the person is content, while the eyes just stare when distressed. Early distress may be indicated by changes when eye contact is no longer given.

Suffering

Suffering is not a question that demands an answer; it is not a problem that demands a solution; it is a mystery that demands a presence. (Anon, quoted in Wyatt J. Matters of Life and Death, Leicester IVP/CMF 1998).

Suffering is a difficult and poorly understood concept. It is a generic concept, and just as there are many different types of physical pain, so too, there are different types of suffering. Loss is one form of suffering, grief is another, and soul pain in a dying child or the family is another form of great suffering. A number of definitions have been offered:

A loss of wholeness and the distress and anguish that accompany it [40].

Suffering occurs when the impending destruction of the person is perceived [41].

Bringing these together in making a start at conceptualising soul pain, the following is a good working definition:

Soul pain is the experience of an individual who has become disconnected and alienated from the deepest and most fundamental aspects of himself or herself [42].

The key words here are, disconnected , alienated and fundamental aspects of self . It is in these words also that some of the symptomatology of soul pain may be found. Soul pain is a deep homesickness having little to do with physical location and everything to do with our longing for the embrace of those who share life with us [in this case, parents and siblings] and our yearning to feel at home in the world [42].

Soul pain cannot be seen or measured as something that is happening in a child's body, it is about what is happening in his or her soul. It is the difference between crying and

P.80

weeping , a kind of malignant sadness . The truth is, none of us knows what the other is suffering. We must try to remember to use our imaginations and let the children also use theirs.

The following poem, written by a young teenager dying from cancer, is a powerful expression of what I perceive as soul pain. She finds herself unable to talk about either her disease or her dying to the person she loves the most, her mother, or to the people who care for her, her father and her doctor. All three of them have silenced her by their own fears and anxieties: Searching For Me by Gitanjali

Disillusioned

Discouraged

Despair writ

On his face

The doctor

Holds my hand

Not my attention

He retreats

The moment

I catch his glance

He hurriedly

Looks away.

Neither he, nor my daddy

Can fool me, no way

It's poor Mom

Who is lost to the world

And relies heavily on God

Little does she realise

I don't even have

A lean chance.

I pity her

And sorry be

For none is there

To share

Her loneliness

Her pain, and

longing, for

only I know

how she cares.

She'll go about

her life, as any

normal human being

only it will be her form

her soul will be searching

for me [44].

Responding to soul pain

The starting premise is that it is impossible for one individual to prescribe for another's soul pain. No matter how well meant and no matter how great the effort, it is not possible for one person to give another person a sense of meaning [45].

However, being with a child in soul pain is often more important than any other intervention you might make, and small interventions may help start the process of helping a child do the work he or she needs to do.

Case Ben was 7 years old when he was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukaemia, with CNS involvement and spinal cord compression. He is now about 4 years post his treatment. He was treated with intensive chemotherapy and irradiation, over about 6 months, most of which was as an in-patient. He lives with his parents, a 4-year-old brother and a 15-month-old sister.

Ben was, and is, a very bright boy. It did not take him long to work out that all was not well, and that he was very ill. He became very uncertain and frightened about his future, and though he could not always make sense of the little information he was picking up, he was not asking for information.

He feared the future. Each tomorrow was seen as heralding increased sickness and pain in his life. The nausea and vomiting from the chemotherapy were distressing, but no more so than the anticipation of his hair loss, change in body image, and time away from home, school, and his friends. He felt isolated because he was no longer like his friends, and could not do what they were doing at home and at school. At every stage, the treatment as well as the disease was a source of great suffering to him and his family. He suffered from the effects of his disease and its treatment on his appearance and abilities. He also suffered unremittingly from his perception of the future.

Recall Cassell's definition of suffering: Suffering occurs when the impending destruction of the person is perceived .

As a way of working with Ben's mother, I asked her to write down the changes she saw in him, and she listed:

general sadness/few smiles;

withdrawn avoids eye contact, especially with professionals;

angry at times verbally and physically;

tearful at times;

concentration span very small;

regressed to sucking his thumb and using a teddy as a comforter;

reduced mobility and weight;

tires quickly and is very lethargic. Needs help with basic things, i.e., toileting, eating and drinking;

Ben has lost his zest for life . He was a child (and hopefully will be again) with lots of energy both physical and emotional.

Impatient.

It is an interesting list of symptoms, some of which can be put down to the side effects of the chemotherapy. Others might well be symptoms of his soul pain. She then went on and asked Ben what he thought and he said:

Everything has changed.

Doesn't think he will ever get better.

Desperately wants to go home.

Angry not being able to run around with other children, especially his brother and sister.

Want to be left alone.

P.81

It seemed to me, as I cared for Ben, that he had become helpless and powerless, in what was for him, a new experience. This in turn, seemed to have undermined his motivation to go on living. He felt that his distress and the anguish caused by his diagnosis was unrelenting and unending, and that his future was possibly hopeless. This suffering reinforced itself in his passivity. His helplessness and hopelessness combined to paralyse him in his bed, from which he would not get up. He had turned his head away from the world. I came to see this suffering as Ben's soul pain . I was acutely and painfully aware of his disconnectedness from what used to bring value, hope and meaning into his life, and I could see that he had distanced himself from what used to bring him consolation and comfort: namely his parents, family, and friends.

Soul pain is something we come to: feel , see , and sense in another [42]. It was clear that this child was suffering. His mother gave him the key to open the door by asking him what had changed, and surprisingly, that was all that was needed. Ben demonstrated the change in behaviour and eye contact noted by Regnard and colleagues [39], which was one of the first clues that he was becoming more and more distressed. They were also the first signs that life was improving for him as he started to make sense of how his world had changed.

Having suggested that children may experience some degree of soul pain, some ways in which we may facilitate its expression will now be considered, while remembering, as Coles suggested:

We are not obliged to try knowing all things or being all things to the people we work with [9].

Children of all ages can express their inner-worlds and all that goes to make up these worlds through play, music, art, image work, and dream work [46]. (See also Chapter 10, Children expressing themselves and Chapter 8, Psychological impact of life-limiting conditions on the child). We could start by asking the question Coles asked the children he was working with:

Tell me, as best you can, who you are what about you matters most, what makes you the person you are. I would then qualify: if you don't want to emphasise any one thing, any one quality or trait or characteristic, then include others [6].

This can be done in words, pictures, play or music, as it may be too painful for the child to do so in words alone. In this way the child can remain in control, and choose to reveal as much or as little as he can cope with [47].

The child, especially during the years from two or three through adolescence, can communicate a great deal of his emotional life through drawing. Children often express themselves more naturally and spontaneously through art than through words. Kramer links the freedom of expression inherent in art to that found in imaginative play, where forbidden wishes and impulses can be expressed symbolically. Even when the child draws a picture that symbolically represents thoughts and feelings that might be too painful to express verbally, he is still able to maintain his ego strength. His art work, therefore, may be used as an indication of his thoughts and emotions [48].

Paediatric clinicians can justifiably say that they are not trained or skilled to work in these media. However, we watch children do these things every day of our working lives: Play is far more than an arena for motor development. It is a mirror of the child's knowledge of his world [49].

Paediatric clinicians and carers can use these media as part of an ongoing emotional assessment of the child, and then refer to an appropriate therapist, such as a clinical psychologist, or an art or music therapist, if they feel unable to work with what the child is presenting to them. It is not necessarily a question of being able to interpret what the child is doing; it is more about being with the child as he or she surprises himself or herself by discovering his or her inner-world [50]. Our role may only be to provide the child with a safe environment, in which to express his or her inner-world.

Bluebond-Langner said that A child who is terminally ill seldom tells what he knows in ways easy to understand. But when one learns to listen and take cues from him, it is soon realised that the child does know the truth, and this is often more than can be borne [21].

Axline [51] supports this statement and suggests that play therapy is An opportunity which is given to the child to play out his feelings and problems just as, in certain types of adult therapy, an individual talks out his difficulties'.

Providing children with this opportunity to discuss, or play out issues related to their illness or impending death, should not necessarily increase their anxieties. Pinkerton, Cushing and Sepion [52] suggest, in fact, that it decreases them, in that it reduces their sense of alienation and isolation from their parents and carers.

Ibberson [53] describes how a 13 year-old girl came to terms with the death of her sister and prepared herself for her own death through music therapy: music became an invaluable source of communication, exploring the anxieties and confusion that Catherine faced as grief and fear came to the fore, while nurturing her innate zest for life.

Children of all ages need to be given a window of opportunity they can open or close, if they so choose, to communicate about their illness or impending death. This is a short conversation between a child and his mother:

It's time to take your antibiotic, son.

No, it is not, mum, it's time to stop taking it.

P.82

Is this child telling his mother that it is no longer any good taking his antibiotic or that she has got the time wrong? Mothers don't usually get the times wrong for their children's medication.

Hymovich [54] found that children find informal ways of communicating: Children choose the people with whom they wish to communicate, as well as control over what they will talk about and when they will talk.

We need to bear in mind that each child we meet will be different. It cannot be assumed, even knowing that children of different ages have different understandings of illness or death and dying, that all children in a given age group will have the same understanding. They all come from different backgrounds and environments, and have had different life experiences. Their personal experience with illness or death, their cognitive abilities, and their religious and cultural backgrounds will all play a part in their understanding and will form their ways of coping with trauma, loss, grief, death and ultimately, their dying. The problem of identifying what each child understands and feels is amplified when having to rely on non-verbal communication and observations with younger pre-verbal children, children with complex neurological diseases or older children who have become silent because of fear.

The only way to gain this information is through good communication with the individual child, be that through therapeutic play, art, music, dream work, story-telling, creative writing, visualization, guided imagery, straight talking with the older child, or just sitting with the child and waiting, watching and wondering what may happen next. All these media may be used to help distressed children express their inner-worlds, where they may start to discern their meaning and their own hopes [55].

These illustrations indicate that soul pain can be explored in children by understanding how children process information and by being aware of the psychopathology of their soul pain. Moreover, we can help this group of children by facilitating them to find ways in which they feel comfortable in expressing their inner-worlds, even though this is not easy to accomplish.

Paediatric clinicians and carers appear to be committed to the concepts of holistic and family-centred care [56, 57, 58, 59]. However, they may be the first to admit, like other groups of clinicians, that they find this dimension of care difficult to address with children, with children from different cultural and religious backgrounds, and children who may be dying [60].

Caring for the soul

Care of the soul would be those aspects of care that help a person connect with his inner self and find the centre of his being. The difference between spiritual and soul is primarily one of transcendence [43].

Care of the soul begins with observance of how the soul manifests itself and how it operates. We can't care for the soul unless we are familiar with its ways [33].

In order to care for the families we work with, we first need to understand how our own soul manifests itself and how we care for it. Children who are dying will at some time think about the ramifications of their illness for their souls as well as for their bodies. On this journey, we are called to be their companion, guide and advocate and we can only do this if we are at home in our own soul. They need our help, but they don't need us to do the journey for them.

Our role as paediatric clinicians and carers is to work with both the child and the whole family to give them all a feeling of security, so that they can start to do the work they need to do in trying to find meaning in their child's pain, suffering, and death.

We must recognise that the most we can do is to prepare and hold the space where the miraculous may happen (cited by Kearney 42).

Preparing and holding a safe and secure or sacred space is what we do when we offer expert and effective care and symptom management, when we help open up blocked channels of communication, and as we work with distressed families who can find no meaning in their child's illness, suffering, or death. If we can find a creative way of responding to the challenge of soul pain, it may open up a path to the very heart of living, even in the shadow of death

When we are mindful observers and respectful listeners to children, we nurture their spirits (souls) and provide an opportunity to connect them fundamentally to themselves and their experiences [61].

Edwards and Davis [62] have described this role well, and it is reproduced here with consent, as a summary of what has been suggested in this chapter and to give guidelines.

Exploring the child's experiences and understanding

Getting to know children and exploring their experiences of events are perhaps the most important parts of the process of helping.

Exploration of the child's experience or problem:

is only possible when sufficient trust and openness have been established in the relationship between the child and helper;

is a prerequisite to enabling a shared understanding of the difficulty and required areas of change/help, and in implementing strategies for helping;

is important in getting to know the child better and enabling the helper to put the child's difficulties into the context of his life circumstances generally;

can in itself be of enormous value in facilitating change, by enabling developments in the child's understanding or perception of events;

has important implications for the development of the relationship between the helper and child, enabling the child to realise that the helper is interested in him or her and not just his or her problem;

can be facilitated with verbal prompts including open and closed questions, multiple choice responses, facilitative comments, such as empathic responses, and using questions which structure and therefore enable a more coherent and clear account to be given;

using open questions most frequently enables the child to tell his or her story in his or her own words;

can use non-verbal modes of expression, including drawings, models/puppets, and play;

can use more structured forms such as the use of sentence/story completion tasks, books, diaries, rating scales, and exploratory games.

P.83

Conclusion

Professionals who use listening skills to hear what the child is expressing within the limits of the developmental and cognitive stage, and who have the courage and imagination to respond or to refer on appropriately are providing good spiritual care [63].

We so often treat children as if we have forgotten what it is like to be a child. These are things we can ill afford to do if we wish to understand what it is like to be a child with terminal illness and to respond appropriately [40].

When it all gets too hard and you are at a loss as to what to do next, it is well worth remembering that old Indian proverb about God: God gave us one mouth and two ears so that we can listen twice as much as we speak.

The children and their families just need us to be there, watching with them, waiting with them, and wondering with them as they surprise themselves. They need us to be truly present to them, and to be ourselves. This work is about a journey , and that journey is to the centre, to the heart of the matter, or, as in the Ring, to the mountain of fire in Mordor . On this journey, we have to engage the child and family, if we are to travel with them, get to the heart of the matter, and help them move on to the next stage of their journey.

References

1. Williams. N. As it is in Heaven, London: Picador, 1999.

2. Garbarino J. and Bedard C. Spiritual challenges to children facing violent trauma, Childhood 1996;3(4):467 78.

3. Kenny. G. Assessing children's spirituality: What is the way forward, Brit J Nurs 1999;8(1):28 32.

4. Larson, B.B., Sayers J.P., and Mccullough, M.E. Scientific Research on Spirituality and Health: A Consensus Report. National Institute for Health Care Research. Rockville, 1997.

5. Meraviglia, M.G. Critical analysis of spirituality and its empirical indicators: Prayer and meaning in life, J Holist Nurs 1999;17(1): 18 33.

6. Shelley, J.A. The Spiritual Needs of Children, USA: Inter-Varsity Press, 1982.

7. Pehler, S.R. Children's spiritual response: Validation of the nursing diagnosis in spiritual distress. Nurs Diag 1997;8(2).

8. Doka, K.J. Suffer the little children; the child and spirituality in the AIDS crisis. In B. Dane and C. Levine, eds. AIDS and the New Orphans. Wesport: Auburn House, 1994, pp. 33 41.

9. Coles, R. The Spiritual Life Of Children, London: Harper Collins, 1992.

10. Sommer, D.R. The Spiritual Needs of Dying Children. Issues Comprehens Pediat Nurs 1989;12:225 33.

11. Davies, B., Brenner, P., Sumner, L., and Worden, W. Addressing Spirituality in Pediatric Hospice and Palliative Care. J Palliat Care 2002;18(1):59 67.

12. McKivergin, M.J. and Daubernimire. M.L. The Healing Process of Presence. J Holist Nurs 1994;12(1):65 81.

13. Goldman, A. and Christie, D. Children with cancer talk about their own death with their families. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 1993;10(3): 223 31.

14. Bluebond-Langner, M. I Know, do you?, 171 181, In Schoenberg, B. et al. Anticipatory Grief, New York: Columbia University Press, 1974.

15. Kubler-Ross, E. To Live Until We Say Good-Bye, Chapter 2, JAMIE , USA: Prentice Hall, 1985.

16. Anthony, S. The Child's Discovery of Death. New York:Brace & Co., 1940.

17. Nagy, M. The child's theories concerning death. J Genet Psychol 1948;73:3 27.

18. Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss. London: Hogarth Press, 1980.

19. Koocher, G. Childhood, death and cognitive development. Developmental Psychology 1973;9:369 75.

20. Swain H. The concepts of death in children. Dissertation Abstr Int 1975;37(2 A):898 9.

21. Bluebond-Langner, M. The Private Worlds Of Dying Children, New Jersey, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1978.

22. Kane B. Children's concepts of death. J Genet Psychol 1979;134: 141 53.

23. Landsdown R. and Benjamin, G. The development of the concept of death in children 5 9 yrs. Child and Dev 1985;11:13 20.

24. Clunies-Ross C. and Lansdown R. The concept of death in children with leukaemia. Child: Care, Health Dev 1988;14: 373 86.

25. Dom Henry, T. Vaisnava Hindu and Ayurvedic Approaches to Caring for the dying. In M. Solomon, A. Romer, K. Helper, and D. Weilsman eds. Innovations in End-of-Life Care Practical Strategies & International Perspectives. Vol 2. USA: Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. Publications, 2001, pp. 223 30.

P.84

26. Tolkien, J.R.R. The Lord of the Rings, 284. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1954, p. 284. Reprinted by permission of Harper Collins Publishers Ltd. Tolkien 1954.

27. Tournier, A Doctor's Case Book in the Light of the Bible. London: SCM Press, 1954.

28. Stoter, D. Spiritual Aspects of Health Care. London: Mosby, 1995.

29. Hillman, J. Suicide And The Soul. Woodstock. USA: Spring Publications, Inc., 1965.

30. Hillman, J. Re-Visioning Psychology. New York: Harper & Row, 1975.

31. Moore, T. Care of the Soul. New York: Harper Collins Books, 1992.

32. Bettelheim, B. Freud & Man's Soul. London: Flamingo, 1983.

33. Autton, N. Pain: An Exploration. London: Darton, Longman & Todd, 1986.

34. Cassell, E. J. The Nature Of Suffering and The Goals of Medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

35. International Association for the Study of Pain: Subcommittee on taxonomy. Pain terms: A list with definitions and notes on usage. Pain 1979;6:249 52.

36. Hain, R. Pain scales in children: a review. Palliat Med 1997;11: 341 50.

37. Saunders, C. and Baines, M. Living With Dying: The Management Of Terminal Disease. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983.

38. Elsdon, R. Spiritual pain in dying people: The nurse's role. Professional Nurse 1995;10(10):641 3.

39. Regnard, C., Matthews, D., Gibson, L., and Clarke, C. Difficulties in identifying distress and its causes in people with severe communication problems. Int J Palliat Nurs 2003;9(4):173 6.

40. Attig T. Beyond Pain: The existential suffering of children. J Palliat Care 12(No 3):20 23.

41. Cassell, E.J. The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine. N Engl J Med, 1982;306(11):639 45.

42. Kearney, M. Mortally Wounded. Dublin: Marino Books, 1996.

43. Lane. J.A. The care of the human spirit. J Professional Nurs 1987; 3(6):332 7.

44. Badruddin, K. Poems of Gitanjali. London: Oriel Press, 1982.

45. Kearney. A Talk Given in London, 1998.

46. D'antonio, I.J. Therapeutic use of play in hospitals. Nurs Clin N Am 1984;19(2):351 9.

47. Bach, S. Life Paints Its Own Span: On The Significance Of Spontaneous Pictures By Severely Ill Children. Switzerland: Daimon Verlag, 1990.

48. McLeavey, K.A. Children's art as an assessment tool. Pediatr Nurs 1979;March/April:9 14.

49. Marino, B.L. Studying infant and toddler play. J Pediatr Nurs 1991;6(1):16 20.

50. Wilson, K. Kendrick, P., and Ryan, V. Play Therapy: A Non-Directive Approach For Children And Adolescents. London: Bailliere Tindall, 1992.

51. Axline, V.M. Play Therapy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1989.

52. Pinkerton, C.R., Cushing, P., and Sepion, B. Childhood Cancer Management. London: Chapman & Hall, 1994.

53. Ibberson, C. A Natural End: One story about Catherine. Br J Music Ther 1996; 10(1):24 31.

54. Hymovich D. The meaning of cancer to children. Semin Oncol Nurs 1995;11(1):51 58.

55. Armstrong-Dailey, A. and Goltzer, S.Z. Hospice Care for Children. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

56. Thompson, J. Family centred care. Nursing Mirror 1985;Feb 13th: 25 28.

57. Casey, A. A partnership with child and family. Senior Nurs 1988; 8(4):8 9.

58. Darbyshire, P. Living with a Sick Child in Hospital. London: Chapman & Hall, 1994.

59. Palmer Care of the sick child by parents: A meaningful role. J Advanced Nurs 1993;18:185 91.

60. Winkelstein, M, L. Spirituality and Death of the Child. In V.B. Carson, ed. Spiritual Dimensions of Nursing Practice Chapter 9. London: Saunders Co., 1989.

61. Thurston C. Ryan J. Faces of God: Illness, healing, and children's spirituality. ACCH Advocate 1996;2(2):13 15.

62. Edwards, M. and Davis, H. Counselling Children with Chronic Medical Conditions. The British Psychological Society Books, 1997.

63. Pfund. R. Nurturing a child's spirituality. J Child Health 2001;4(4):143 8.

64. Cobb, M. The Dying Soul. Buckingham: Open University Press, 2001.

65. Stoter, D. Spiritual Aspects of Health Care. London: Mosby, 1995, p. 8.

66. Goodliff, P. Care in a Confused Climate: Pastoral Care and Postmodern Culture. London: Darton: Longman & Todd, 1998.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 47