Story

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

Plays, movies, and television are all media that involve storytelling and linear narratives. When an audience participates in these media, they experience a story that progresses from one point to the next as determined by an author. The audience is not an interactive participant in these media and cannot change the outcome of the story. Game systems are essentially different in this respect: their players are interactive participants who can change the outcome of the game. Because of this, and because game systems are usually nonlinear, it's difficult to integrate traditional storylines into games.

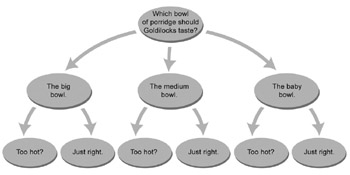

Figure 4.13: Branching story structure

In most games, story is actually limited to backstory: sort of an elaborate version of premise. The backstory gives a setting and context for the game's conflict, and it may create motivation for the characters, but its progression from one point to the next is not affected by gameplay. An example of this is the trend of inserting story chapters into the beginning of each game level, creating a linear progression that follows a traditional narrative arc interspersed with gameplay that does not affect how the story plays out. Games like the War- Craft or StarCraft series follow this model in their single-player modes. In these games, the story points are laid out at the beginning of a level, and the player must succeed in order to move on to the next level and the next story point.

There are some game designers who are interested in allowing the game action to change the structure of the story, so that choices the player makes affect the eventual outcome. There are several ways of accomplishing this. The first, and simplest, is to create a 'branching' storyline. Player choices feed into several possibilities at each juncture of a structure like this, causing predetermined changes to the story. The diagram in Figure 4.13 shows an example of this type of story structure using a simple fairytale story we are all familiar with.

One of the key problems with branching storylines is their limited scope. Player choices may be severely restricted in such a structure, causing the game to feel simplistic and unchallenging. In addition, some paths may create uninteresting outcomes. Many game designers feel there's better potential for use of story in games if the story emerges from gameplay, rather than from a predetermined structure. For example, in The Sims, players have used the basic elements provided by the formal system to create innumerable stories involving their game characters. The system provides features that support this emergent storytelling, including tools for taking snapshots of the gameplay, arranging the snapshots in a captioned scrapbook, and uploading the scrapbook to the web to share with other users.

by Jesse Schell, Professor of Entertainment Technology, Carnegie Mellon University

Myth #1: Interactive Storytelling Has Little to Do with Traditional Storytelling

I would have thought that by this day and age, with story-based games taking in billions of dollars each year, this antiquated misconception would be obsolete and long forgotten. Sadly, it seems to spring up, weedlike, in the minds of each new generation of novice game designers. The argument generally goes like this:

'Interactive stories are fundamentally different from noninteractive stories, because in non-interactive stories, you are completely passive, just sitting there, as the stories plods on, with or without you.'

At this point, the speaker usually rolls back his or her eyes, lolls his or her tongue, and drools to underline the point.

'In interactive stories, on the other hand, you are active and involved, continually making decisions. You are doing things, not just passively observing them. Really, interactive storytelling is a fundamentally new art form, and as a result, interactive designers have little to learn from traditional storytellers.'

The idea that the mechanics of traditional storytelling, which are innate to the human ability to communicate, are somehow nullified by interactivity is absurd. It is a poorly told story that doesn't compel the listener to think and make decisions during the telling. When one is engaged in any kind of storyline, interactive or not, one is continually making decisions: 'What will happen next?' 'What should the hero do?' 'Where did that rabbit go?' 'Don't open that door!' The difference only comes in the participant's ability to take action. The desire to act, and all the thought and emotion that go with that are present in both. A masterful storyteller knows how to create this desire within a listener's mind, and then knows exactly how and when (and when not) to fulfill it. This skill translates well into interactive media, although it is made more difficult because the storyteller must predict, account for, respond to, and smoothly integrate the actions of the participant into the experience.

The way that skilled interactive storytellers manage this complexity, while still using traditional techniques, is through the means of indirect control, using subtle means to covertly limit the choices that a participant is likely to make. This way, masterful storytelling can be upheld, while the participant still retains a feeling of freedom. For it is this feeling of freedom, not freedom itself, which must be preserved to tell a compelling interactive story.

Myth #2: Interactive Storytelling Has Little to Do with Traditional Game Design

I am amazed by the vast number of would-be game designers who whine that while they are brimming with great game design ideas, they lack the large team required to implement these ideas, and therefore they are unable to practice their craft.

This is nonsense of the highest order. A game is a game is a game. The design process for a boardgame, a card game, a dice game, a party game, or an athletic game is no different from the process of designing a videogame. Further, a solo designer can fully develop working versions of these nonelectronic games in a relatively short time. Making and analyzing traditional games can often be far more instructive than trying to develop a fully functioning videogame. You can learn much more about game design in a much shorter time, and you won't have to concern yourself with the technical headaches and limitations involved with interactive digital media. If you really want to understand how to create good interactive entertainment, first study the classics, and then try to improve on them. Riddles, crossword puzzles, chess, poker, tag, soccer, and thousands of other beautifully designed interactive entertainment experiences existed long before the world even knew what a computer was.

To sum up: New technologies allow us to mix together stories and games in interesting ways, but there are very few elements that are fundamentally new-most designs are simply new mixtures of well-known elements. If you want to master the new world of interactive storytelling, you would be wise to first understand the games and stories of old.

Author Bio

Jesse Schell is a Professor of Entertainment Technology at Carnegie Mellon, specializing in game design. Formerly, he was Creative Director of the Walt Disney Imagineering VR Studio, where his job was to invent the future of interactive entertainment for the Walt Disney Company. Jesse worked and played there for seven years as designer, programmer, and manager on several projects for Disney theme parks and DisneyQuest (Disney's chain of VR entertainment centers). His most recent work at Disney involves design of family-friendly massively multiplayer worlds, such as Disney's Toontown Online.

In addition to simulation games, other genres are also addressing the possibility of designing for emergent storytelling. This includes games like Black & White, which combine elements of simulation with strategy and role-playing, as well as action games like Half-Life, which have 'triggered' story sequences depending on player actions, and Halo, which uses artificial intelligence techniques in nonplayer characters to create unique and often dramatic responses to player actions.

While it remains to be seen if these attempts to allow emergent storytelling to arise out of formal game structures will have a significant impact on games, it's certain that game designers are still searching for better ways to integrate story into their systems without diminishing gameplay.

Exercise 4.8: Story

Pick a game that you feel successfully melds its storyline with the gameplay. Why does this game succeed? How does the plot unfold as the game progresses?

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 162