Publishers

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

Genres Of Gameplay

In addition to platforms, another important way of looking at the game industry is in terms of game genres. You’ve probably noticed by now that we did not emphasize the concept of genre in any of our discussions about design. This is because we believe genres are a mixed blessing to a game designer.

On one hand, genres give designers and publishers a common language for describing styles of play: They form a shorthand for understanding what market a game is intended for, what platforms the game will be best suited to, who should be developing a particular title, etc. On the other hand, genres also tend to restrict the creative process and lead designers toward tried and true gameplay solutions. We encourage you to consider genre when thinking about your projects from a business perspective, but not to allow it to stifle your imagination during the design process.

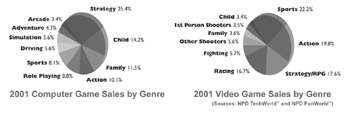

That said, genre is a big part of the today’s game industry, and as a designer, it’s important for you to understand the role it plays. The top-selling genres differ between platforms, and between market segments. When publishers look at your game, they want to know where it falls in current buying trends of the gaming audience. Without the benefit of genre, this would be a difficult task.

Although we don’t want you to inhibit your design process by too great an emphasis on genre, designers can learn something from the publishers’ emphasis on creating product for players who enjoy specific types of gameplay. In order to better understand today’s top-selling genres, we’ve briefly listed their key differentiators.

Action games

Action games emphasize reaction time and hand- eye coordination. While store shelves are packed with titles that utilize 3D graphics and the first-person perspective, this is more of a trend than a genre requirement. Action games can include titles as disparate as Unreal Tournament, Grand Theft Auto III, and Tetris. Action as a genre often overlaps with other genres, for example, Grand Theft Auto III is an action game, but it is also a driving/racing game and an adventure game. Tetris is an action game and a puzzle game. The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker is an action adventure game, and Diablo is considered a role-playing action game. Action games are without exception real-time experiences, with an emphasis on time constraints for performing physical tasks.

Figure 15.4: Top-selling genres in 2002

Title: Production Intern, Vivendi Universal Games / Student, University of Southern California

Project list: Six unannounced titles with Vivendi Universal Games

How did you get into the game industry?

I always wanted to get into the industry, but like most people had trouble finding an open door. I thus spent all my time learning about the industry so I would be prepared when an interview came up. I would read about the industry on a daily basis, analyze reviews, and play as many different games as possible. I would also take every opportunity to talk to people in the industry, you’d be surprised how eager some people are to simply share their experiences or give some inspirational words of wisdom.

During our Spring 2003 career fair at USC, I met the recruiter from Vivendi Universal Games who was looking for applicants to their summer internship program. I jumped at the opportunity, and kept in touch with her for several months after sending in my application. I was also fortunate enough to meet their VP of Product Development during my game design class at USC and again at E3. Through continuous networking I finally scored an interview and was lucky enough to be selected for the position.

What’s the most interesting thing that’s happened on the job

I was responsible for directing and creating game trailers for internal demonstration and promotion. I would constantly look at competitive titles, reviews, previews, and videos to compare and thus improve our current projects, along with perform market research to evaluate risk in new concepts.

Since I was with a publisher, we often had up and coming developers pitch us projects in the hope of gaining a publishing contract. On one specific occasion, a developer came in with a great looking game almost 3/4 complete. I was amazed at how innovative and polished the game looked without prior publishing overhead. It was a great opportunity to see how beautiful a game can be made without having a ridiculous amount of time or money.

What experiences have taught you the most about game design?

In the School of Cinema at USC, I took a class in game design taught by the authors of this book. The class took an in-depth look at how games operate as interactive systems, and analyzed game history in an attempt to unfold why certain design traits are successful and why others fail.

During my internship one producer instructed me to map out the levels of certain games on paper, and write walkthroughs as though I were explaining the level to programmers, artists, and sound designers. The exercise made me realize how every room in a level should have a purpose, and how on every level the player should be learning new tactics or introduced to new challenges.

Where do you hope to be in five years?

I hope to be working with a major publisher or developer, with an opportunity to give input on design and the creative process. I am fascinated by the current trend in hybrid genres, and hopefully I will have a chance to someday work with these innovative projects.

What words of advice would you give to a person trying to get into the industry today?

Be passionate and be persistent. Play games from all genres and platforms, read about the industry on a daily basis, and constantly search for internships or entry-level positions. Use these positions as a chance to network with employees and prove that you can handle greater responsibility.

Jim Vesella, left, testing one of his game prototypes with other student designers

Strategy games

Strategy games focus on tactics and planning, as well as the management of units and resources. The themes tend to revolve around conquest, exploration, and trade. Included in this genre are Masters of Orion, Civilization, Settlers, and Risk. Originally, most strategy games drew upon classic strategy boardgames and adopted turn-based systems, giving players ample time to make decisions; however, the popularity of WarCraft II and Command & Conquer changed everything, ushering in the subgenre of real-time strategy games. Today there are even action/strategy games, which combine physical dexterity with strategic decisionmaking. Uprising and Shogun: Total War are examples that fit into this hybrid genre. Pure strategy games like chess and checkers are increasingly rare in the world of digital entertainment, as the market has moved toward incorporating some elements of chance with the strategic decision making, as well as plenty of action.

Role-playing games

Role-playing games revolve around creating and growing characters. They tend to include rich storylines tied into quests. The paper-based system of Dungeons & Dragons is the great-grandfather of this genre, which has inspired such digital games as Baldur’s Gate, Dungeon Siege, EverQuest, and the pioneering NetHack. All role-playing games begin and end with the character. Players typically seek to develop their characters, while managing inventory, exploring worlds, and accumulating wealth, status, and experience. Many role-playing games take weeks, if not months, to complete, and the play can be quite slow when compared to action games. However, a new breed of role-playing/action games, made popular by Diablo, has sprung up and combines traditional elements with fast-paced twitch play.

Racing/driving games

Racing/driving games come in two flavors, the real-world simulations, like NASCAR Thunder, F1 Career Challenge, and Monaco Grand Prix Racing Simulation, and the popular fantasy racing games, like Carmageddon, Test Drive, and Diddy Kong Racing. One thing that all of these games have in common is that you’re racing and you’re in control. This includes the horse racing games, like G1 Jockey and Gallop Racer, and the spaceship racing games, like Star Wars Episode I: Racer. Arguably, you could even include luge and ski races, although they are really sports games. But then again, there’s a big overlap between racing and sports. To differentiate the two, another iconic part of racing games tends to be the point of view (POV): the cockpit with instruments POV, the cockpit-removed POV, the chase POV, and the overhead POV. How these games use viewpoints, instrumentation, objects whizzing past, and sound effects plays a large part of creating the illusion of speed and control which makes racing games so addictive.

Sports games

Sports games are, quite simply, simulations of sports like tennis, football, baseball, soccer, etc. Since the success of Pong, simulations of sports have always made up a strong segment of the digital game market. Some of the most popular sports games today are Madden NFL, FIFA Soccer, NBA Jam, as well as Sega Bass Fishing and Tony Hawk Pro Skater. Most sports titles rely on real-world games for their rules and aesthetics, but increasingly, there’s a new breed of sports titles that take more creative liberty, like Def Jam Vendetta, which combines hip-hop celebrities, wrestling, and fighting. Many sports games involve team play, season play, tournament modes, and other modes which mimic sporting conventions.

Simulation/building games

Simulation/building games tend to focus on resource management combined with building something, whether it’s a company or a city. Unlike strategy games, which generally focus on conquest, these games are all about growth. Many simulation/building games mimic real-world systems and give the player the chance to manage her own virtual business, country, or city. Examples include: The Sims, SimCity, RollerCoaster Tycoon, SimAnt, Gazillionaire, and Capitalism. One of the key aspects of simulation games is the focus on economy and systems of trade and commerce. Players tend to be given limited resources to build and manage the simulation. Choices must then be made carefully because an overemphasis on developing one part of the simulation results in the failure of the entire system. Another important factor in these games is the balance between direct and indirect control. Players are often given direct control over construction, and placing or purchasing items, but only have an indirect influence over other aspects of management. This tension provides a nice dynamic as the player struggles to maintain control over the growth of the simulation.

Flight and other simulations

Simulations are action games that tend to be based on real-life activities, like flying an airplane, driving a tank, or operating a spacecraft. Flight simulators are the best example. These are complex simulators that try to approximate the real-life experience of flying an aircraft. These cannot be put squarely in the action camp because they aren’t focused on twitch play and hand-eye coordination, but instead require the player to master realistic and often complex controls and instrumentation. Good examples include Microsoft Flight Simulator, Spearhead, and Jane’s USAF. These types of simulations usually appeal to airplane and military buffs, who want as realistic an experience as possible.

Adventure games

Adventure games emphasize exploration, collection, and puzzle-solving. The player generally plays the part of a character on a quest or mission of some kind. Early adventure games were designed using only text, their rich descriptions taking the place of today’s graphics. Examples include the text-driven Adventure and Zork, as well as graphic adventures like Myst. Today’s adventure games are often combined with elements of action, such as Jak and Daxter or Ratchet & Clank. Shigeru Miyamoto, the creator of the Zelda series of adventure games, summed up the nature of the adventure game in his comment that“the state of mind of a kid when he enters a cave alone must be realized in the game. Going in, he must feel the cold air around him. He must discover a branch off to one side and decide whether to explore it or not. Sometimes he loses his way.”[4 ]Although characters are central in adventure games, unlike role-playing games, they are not a customizable element and do not usually grow in terms of wealth, status, and experience. Some action-adventure games, like Ratchet & Clank, do have the concept of an inventory of items for their characters, but most rely on physical or mental puzzle-solving, not improvement and accumulation, for their central gameplay.

Edutainment

Edutainment combines learning with fun. The goal is to entertain while educating the user. Topics range from reading, writing, and arithmetic to problem-solving and “how to” games. Most edutainment titles are targeted at kids, but there are some which focus on adults, especially in the areas of acquiring skills and self improvement. Good examples of kids edutainment software include Putt-Putt Saves the Zoo, Reader Rabbit’s Kindergarten, and Curious George Learns Phonics, and for adults, Sierra’s Driver’s Education, a simulation that teaches you how to drive safely, and Chutes and Lifts, a simple online game that helps foreign speakers to learn and read English.

Title Project list

QA Tester, Vivendi Universal Games

-

Battlestar Galactica: QA

-

Several unannounced titles: QA

How did you get into the game industry?

I always dug videogames, being a member of the Nintendo generation, and all, but it was always just recreation. It was in college that I really began to appreciate the design aspects. So I threw myself into it, and after being encouraged to pursue it, I went looking for a career in games. Fortunately, I had a good friend in a QA department who was awesome enough to make sure my resume got to the right people. I am told by nearly everybody that QA is the best way to get your foot in the door, so here I am, climbing the ladder.

What’s the most interesting thing that’s happened on the job?

Many of my best stories right now are unfortunately inside jokes, though I often don’t realize they’re inside jokes until I try to tell my girlfriend about this hilarious bug we found or this bizarre e-mail from a developer and can’t help but notice that she isn’t laughing. I used to work for an architecture firm and the resident engineer often laughed out loud about some engineering-related flub on a plan. The rest of us in the office came to the conclusion that it was the kind of joke that was only funny if you had a masters in mechanical engineering; I’m getting the feeling that the same is true of those of us in the gaming industry. We have our own subculture and our own unique brand of humor.

As far as war stories go, I have pulled a couple of eighteen-hour days while the game was in final candidate. It’s a bit of a bonding experience when you’re working with the rest of your crew and you watch the sun both set and rise again before your work is done. Plus, if you're lucky, you will get to watch the associate lead spontaneously burst into a funny little jig somewhere around 4:00 in the morning when the build that took three hours to upload from England turns out to be corrupted or incomplete. That’s always a good time.

What experiences have taught you the most about game design?

QA is a great way to see the game slowly evolve over time. I just finished two months of core testing on a game. Every few days you get a new build and you see the changes that were implemented and then you, as a tester, have as one of your jobs the task of seeing if the changes were beneficial to the game. It’s like being able to peek over the designer’s shoulder and watch the designer work.

Depending on your situation, you may even be allowed to offer suggestions. It’s a real rush when you make a suggestion and then, a few days later, you’re playing the newest version and you say, “Oh wow, they actually did it.”

Where do you hope to be in five years?

I’m doing all this because I want to write games, and I make sure that I tell everyone constantly that what I really want to do is write. I’ll write the cut scenes, I’ll write manual, I’ll write the surveys on those little postcards that fall out of the box when you open the game, it doesn’t matter.

Eventually, of course I want to write the actual game. I’m not really a designer, but I look forward to collaborating with designers. Five years from now, it would be awesome to overhear even one seventeen year-old saying, “The game is great and the story is superb.” In general, it would be a kick to hear some seventeen year-old say “superb,” now that I think about it.

If I had one wish, though, I would also like to overhear said seventeen-year-old tell his buddy, “This is the first game I’ve played in a long time where the ending doesn’t suck.” A lot of the games I’ve played lately just stink when you get to the end. The game was great and the story was good and you’ve put a ton of hours into beating the sucker, only to get to the end and see a two-minute (if you’re lucky) cut scene that is “blah” at best and then the credits. Where’s the payoff? Where’s the drama? Where’s your reward? I’d like to make my mark as the writer whose games have an ending that’s worth the trouble of unlocking.

What words of advice would you give to a person trying to get into the industry today?

Make friends. Don’t schmooze. But do make friends and make sure they know what you can do and what you want to be doing. You never know when they might come across an opportunity, and you want as many people as possible to think of you when that happens.

I've been noticing that it’s easy to get a job in QA. It’s keeping the job that’s tough. Really throw yourself into it. Make yourself invaluable. A mentor of mine in college always said, “Be excellent at whatever you do and you won’t do it for long,” and I think that’s great advice for people starting out at the bottom. QA is a rough job and lacks glamour, but if you’re a hard worker and your work is quality, you’ll get noticed.

My last piece of advice is related to that. Keep doing a good job once you’ve started. I know of someone who started doing very well but then slacked off once he knew the lead thought he was doing a good job. The lead also noticed he was slacking off, and that sort of thing can really harm you, especially when you’re just starting out.

Children’s games

Children’s games are designed specifically for kids between the ages of two and twelve. These games may have an educational component, but the primary focus is on entertaining. Nintendo is a master at creating these games, though its franchises such as Mario and Donkey Kong are also loved by adults. Other examples include Disney’s Aladdin Activity Center, Kidsoft’s Ozzie’s Funtime Garden, and Humongous Entertainment’s Freddi Fish series.

Family and mass-market games

Mass-market games are typified by the fact that they are meant to be enjoyed by everyone: male and female, old and young. This means they eschew twitch play, violence, and complex gameplay in favor of attracting the broadest possible audience. Most of the time these are simple games, like those found on Yahoo!’s game site, where you’ll see everything from Canasta to Gem Drop to Literati. Other examples include games like Trivial Pursuit, Scrabble, Yahtzee, and Monopoly. One of the most popular types of family game is the game show. The You Don’t Know Jack series, as well as the versions of Jeopardy! and Wheel of Fortune made for almost every platform available are perennial family favorites.

Puzzle

Puzzle games incorporate the solvable systems(i.e., puzzles) into the overall competitive system of a game. Tetris is probably the most famous digital puzzle game ever made, but as you’ll find if you look closely, many games include puzzles, including most role-playing games and practically all adventure games. Myst is a good example of an adventure game that is clearly a series of puzzles. Puzzle games may emphasize story, as in Myst, or action, as in Tetris. They may also include elements of strategy, as in Scrabble or solitaire, or construction, as in The Incredible Machine.

Exercise 15.1: Your Game’s Genre

What genre does your original game fit into? And why does it fit this genre? Given this information, what platform should your game be released on and who is your target audience?

[4 ]David Sheff, Game Over: How Nintendo Conquered the World” (New York: Vintage Books, 1994), p. 52.

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 162