Tools For Identifying Key Knowledge Resources And Players

Social Network Analysis

One of the biggest difficulties organisations face today, particularly those that have a flexible, mobile and global workforce, is knowing who knows who and who knows what. Although there are formal systems for communicating and channelling information within organisations, a lot of the information that people use in their day-to-day work comes from their informal networks.

Networking has been identified as a crucial skill in knowledge-based businesses as it is the means by which individuals acquire and develop business-critical knowledge. Shapiro and Varian point out that ‘Whether real or virtual, networks have a fundamental economic characteristic: the value of connecting to a network depends on the number of other people connected to it . . . other things being equal, it is better to be connected to a bigger network than a smaller one. It is this “bigger is better” aspect of networks that gives rise to the positive feedback so commonly observed in today’s economy’ (Shapiro and Varian, 1999:174).

However, given the changing landscape of careers, networking is also important because of the way in which it contributes to the development of social capital. Through networking individuals build appropriate support structures, that are seen as being important for ensuring continuing psychological health, particularly when experiencing career transitions (Minor, Slade and Myers, 1991).

So how can organisations uncover the informal networks that exist within their organisation, as well as the different roles that people play within these networks?

A tool that seems to be gaining in popularity within the business world is Social Network Analysis. However, this is not a new tool. It evolved from the work of a group of social anthropologists, Barnes, Mitchell and Bott, in the 1950s and 1960s[3]. In its original form, Social Network Analysis was used to gather and analyse information about people’s social support networks in a systematic way. From Burns et al.’s pioneering work four key categories of social support were identified:

-

Informational support – the provision of information

-

Instrumental support – support that is of a more practical nature

-

Companionship – i.e. friendship

-

Emotional support – this is support that is linked to areas of a more intimate nature such as self-confidence and self-esteem

The way in which individuals mobilise support can be broken down into two categories. The first is ‘solicited requests’, this is where an individual actively seeks help from others. The second is ‘unsolicited requests’ where support is volunteered without an individual having directly to ask for it. The size, density and level of interconnectedness of an individual’s support network all have a bearing on the type, and speed, at which support can be mobilised.

Mobilising social support does have a number of associated costs. One cost is that of having an unbalanced exchange process, i.e. an unequal exchange of resources between individuals. Women in particular can suffer from ‘network overburden’ as they are often more responsive to requests for help, than men. In certain contexts, women may have limited access to supportive helpers e.g. when working in male-dominated organisations. Other costs associated with mobilising social support include: not wanting to create a negative impression by admitting that you have a problem which you cannot solve yourself; the issue of ensuring confidentiality, as well as not wanting to become dependent on others for support.

How are organisations using Social Network Analysis to help them manage their knowledge?

One way is in identifying the informal networks that exist within the organisation, how information flows through these networks, and the different roles that people play in this process. Used appropriately, Social Network Analysis can help identify:

Knowledge connectors – individuals who are good at linking different people within networks. The people who can be heard saying ‘I don’t know the answer to that myself, but I know a man/ woman who will’. These individuals have a good insight into who knows what and who knows who, and thus are able quickly to direct others to the information, or person, that colleagues are looking for. PAs and administrative staff are often very good at playing the role of knowledge connectors, as their work brings them into contact with lots of different people, for different reasons.

Knowledge brokers – these individuals help keep different subgroups within the network together, by communicating what is happening within these different sub-groups.

Boundary spanners – these individuals form links with other networks, either within the organisation, or outside. They tend to have a broad overview of different functional areas and what they are doing. Boundary spanners can often be formal connectors between departments, because of the insights that they have into what other departments are doing.

Knowledge specialists – these individuals are the ones that others consult when they need some expert advice. These may not be the same people whom the formal system recognises as being a particular subject expert. This could be because the individuals themselves prefer to play a peripheral role, rather than be in the spotlight. They may be the ones who write the leading-edge articles, but not the ones who volunteer to give presentations at conferences, either internal or external.

What is important from an organisation’s perspective is to recognize that these different roles exist and that they are each valuable in their own way. Armed with this information, organisations can then make more informed decisions about their reward and recognition, retention planning, succession planning, career management systems. In addition, line managers can take these informal roles into account when agreeing key task and deliverables with team members.

Other areas in which organisations can benefit from using Social Network Analysis are the recruitment and exit interview process, career management programmes, management development programmes, to highlight where individuals need to build more, or develop closer, working relationships.

In my own practitioner work, helping individuals who are in some form of career transition, I use Social Network Analysis as a way of helping these individuals review their personal networks. We look at the people in their existing network and the different types of support that each contact provides. This helps individuals become more aware of the gaps between support needed and received. We also look at the level of inter-connectivity between contacts in their network. This is important for information flow. Connectivity can also affect the extent to which individuals have to ask for direct help, as opposed to help being offered. Reviewing one’s social network when in some form of transition is important as it is likely that individuals will need to invest in building new relationships, as well as possibly letting go of some existing relationships.

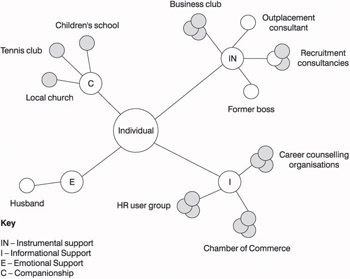

Figure 11.1 provides an example of the social network of an individual making the transition from a traditional career to an independent career, drawn from my own research (Evans, 2001).

Figure 11.1: Example of a changing social network during a career transition

This particular individual was interesting in that in the immediate period prior to pursuing an independent career she had been on sabbatical, and had not worked for a period of around eighteen months. Part of her networking strategy during her career transition involved renewing old contacts (indicated by the unshaded nodes in Figure 11.1), as well as building new contacts (indicated by the shaded nodes in Figure 11.1). Her objective in renewing old contacts was twofold. First, to update her network contacts on her future plans. Second, to enlist their support in helping her make connections with organisations that might have a need for her expertise.

As Figure 11.1 shows the type of support she received from the different contacts in her network varied (indicated by the capital letters in each of the network nodes). As she was no longer in traditional employment most of her Companionship needs were satisfied through the contacts in her community networks: the local tennis club, local church and her children’s school.

Most of her Informational Support needs were met through more formal bodies, such as an HR User Group that she belonged to, as well as her local Chamber of Commerce. Instrumental Support (i.e. practical support) was provided through her contacts in recruitment consultancies, business clubs, as well as an existing contact in an outplacement consultancy. Looking at her social network we can see that there was no interconnectivity between the different groups, so the information flow was unidirectional and tightly bounded.

Of course what we must remember is that social networks are not static entities, they are subject to change. People come and go. Relationships form and end. As a key resource in today’s knowledge rich world networks need active management, both personally and for the organisation as a whole.

[3]Geoff Mead. A Winter’s Tale: myth, story and organisations. Self & Society, Volume 24, No. 6, January 1997.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 175