Concepts, Rules, and Examples

Property, Plant, and Equipment

Property, plant, and equipment (also variously referred to as plant assets, or fixed assets, or as PP&E) is the term most often used to denote tangible property to be used in a productive capacity that will benefit the enterprise for a period of greater than one year. This term is meant to distinguish these assets from intangibles, which are long-term, generally identifiable assets that do not have physical substance, or whose value is not fully indicated by their physical existence.

There are four concerns to be addressed in accounting for fixed assets.

-

The amount at which the assets should be recorded initially on acquisition;

-

How value changes subsequent to acquisition should be reflected in the accounts, including questions of both value increases and possible decreases due to impairments;

-

The rate at which the amount the assets are recorded should be allocated to future periods; and

-

The recording of the subsequent disposal of the assets.

Initial measurement.

All costs required to bring an asset into working condition should be recorded as part of the cost of the asset. Examples of such costs include sales or other nonrefundable taxes or duties, finders' fees, freight costs, site preparation and other installation costs, and setup costs. Thus, any reasonable cost incurred prior to using the asset in actual production involved in bringing the asset to the buyer is capitalized. These costs are not to be expensed in the period in which they are incurred, as they are deemed to add value to the asset and indeed were necessary expenditures to obtain the asset, provided that this does not lead to recording the asset at an amount greater than fair value.

Estimated costs to dismantle or remove spent equipment or to restore property, when subject to accurate determination and if constituting a legal or constructive commitment by the reporting entity, are to be recognized over the life of the related asset. Before IAS 16 was amended in 1998, this was accomplished by one of two acceptable means. First, these costs could have been estimated and used to reduce the estimated residual value of the asset, thereby increasing periodic depreciation charges (potentially even to the extent that a negative net book value would result, representing the net obligation for costs associated with asset retirement, less salvage value). Alternatively, the estimated costs could have been accrued periodically, by a charge to current operations and a credit to a provision for an estimated liability. The overall impact on the financial statements would have been equivalent under either approach.

In order to conform to the requirements set forth in IAS 37, Provisions, Contingent Liabilities, and Contingent Assets, IAS 16 was amended with regard to the accounting for estimated costs of asset retirement obligations. Under the current standard, the elements of cost to be incorporated in the initial recognition of an asset are to include the estimated costs of its eventual dismantlement. That is, the cost of the asset is "grossed up" for these estimated terminal costs, with the offsetting credit being posted to a liability account. It is important to stress that this only applies when all the criteria set forth in IAS 37 for the recognition of provisions are met. These criteria are that a provision will be recognized when (1) the reporting entity has a present obligation, whether legal or only constructive, as a result of a past event; (2) it is probable that an outflow of resources embodying economic benefits will be required to settle the obligation; and (3) a reliable estimate can be made of the amount of the obligation.

For example, assume that it were necessary to secure a government license in order to construct a particular asset, such as a power generating plant, and a condition of said license would be that at the end of the expected life of the property the owner would dismantle it, remove any debris, and then restore the land to its previous condition. These conditions would qualify as a present obligation resulting from a past event (the plant construction), which will probably result in a future outflow of resources. The cost of doing this, while perhaps challenging due to the long time horizon and the possible intervening evolution of technology, can normally be estimated. Per IAS 37, a best estimate is to be made of the future costs, which is then to be discounted to present value. This present value is to be recognized as an additional cost of acquiring the asset.

The cost of dismantlement and similar legal or constructive obligations do not extend to operating costs to be incurred in the future, since those would not qualify as "present obligations." The precise mechanism for making these computations is addressed in Chapter 12.

If estimated costs of dismantlement, removal, and restoration are included in the cost of the asset, the effect will be to allocate this cost over the life of the asset through the depreciation process. While not explicitly addressed by either IAS 37 or the revisions to IAS 16, logic suggests that, if originally recorded at discounted present value, each period the provision (i.e., the estimate liability) should be accreted, so that at the expected date on which the expenditure is to be incurred it will be appropriately stated. The offset to this accretion should be reported as interest expense or a similar financing cost. It should not be added to the cost of the asset to which the estimated dismantlement costs related.

In certain cases, other costs will be incurred during the initial break-in period. These costs may, alternatively, be referred to as start-up or preproduction costs. Under the provisions of IAS 16, these costs are not to be added to the amount recorded for the asset unless they are absolutely necessary to bring the asset to a workable condition. Notwithstanding this rule, this remains an area of subjective judgment; under many circumstances there will be justification for adding certain costs, such as those associated with materials used in testing or adjusting the machinery or equipment in order to place it into actual production. If these amounts are significant and incurrence of the costs is a necessary precedent to using the asset, they should be added to the carrying amount of the asset. On the other hand, losses incurred in the early stages of actually employing the asset in its intended use clearly cannot be capitalized, but instead must be charged to expense as incurred, as these are not assets (i.e., these do not represent economic benefits that will later be received by the entity).

While interest costs incurred during the construction of certain assets may be added to the cost of the asset (as described below), if an asset is purchased on deferred payment terms, the interest cost, whether made explicit or imputed, is not part of the cost of the asset. Accordingly, such costs should be expensed currently as interest charges. If the purchase price for the asset incorporates a deferred payment scheme, only the cash equivalent price should be capitalized as the initial carrying amount of the asset. If the cash equivalent price is not explicitly stated, the deferred payment amount should be reduced to present value by the application of an appropriate discount rate. This would normally be best approximated by use of the enterprise's incremental borrowing cost for debt having a maturity similar to the deferred payment term.

Administrative costs, as well as other categories of overhead, are not normally allocated to fixed asset acquisitions, despite the fact that some such costs, such as the salaries of the personnel who evaluate assets for proposed acquisitions, are in fact incurred as part of the acquisition process. As a general principle, administrative costs are expensed in the period incurred. On the other hand, truly incremental costs, such as a consulting fee or commission paid to an agent hired specifically to assist in the acquisition, may be treated as part of the initial amount to be recognized.

Initial recognition of self-constructed assets.

Essentially the same principles that have been established for recognition of the cost of purchased assets also apply to self-constructed assets. All costs that must be incurred to complete the construction of the asset can be added to the amount to be recognized initially, subject only to the constraint that if these costs exceed the recoverable amount (as discussed fully later in this chapter), the excess must be expensed currently. This rule is necessary to avoid the "gold-plated hammer syndrome," whereby a misguided or unfortunate asset construction project incurs excessive costs that then find their way onto the balance sheet, consequently overstating the entity's current net worth and distorting future periods' earnings. Of course, internal (intracompany) profits cannot be allocated to construction costs.

Self-constructed assets may include, in addition to the range of costs discussed earlier, the cost of borrowed funds used during the period of construction. Capitalization of borrowing costs, as set forth by IAS 23, is discussed in a later section of this chapter.

The other issue that arises most commonly in connection with self-constructed fixed assets relates to overhead allocations. While capitalization of all direct costs (labor, materials, and variable overhead) is a well-settled matter in accounting thought, a controversy exists regarding the proper treatment of fixed overhead. Two alternative views of how to treat fixed overhead are to

-

Charge the asset with its fair share of fixed overhead (i.e., use the same basis of allocation used for inventory); or

-

Charge the fixed asset account with only the identifiable incremental amount of fixed overhead.

While international standards do not address this concern, it may be instructive to consider nonbinding guidance included in US GAAP. AICPA Accounting Research Monograph 1 has suggested that

-

... in the absence of compelling evidence to the contrary, overhead costs considered to have "discernible future benefits" for the purposes of determining the cost of inventory should be presumed to have "discernible future benefits" for the purpose of determining the cost of a self-constructed depreciable asset.

The implication of this statement is that a logic similar to what was applied to determining which acquisition costs may be included in inventory might reasonably also be applied to the costing of fixed assets. Also, consistent with the standards applicable to inventories, if the costs of fixed assets exceed realizable values, any excess costs should be written off to expense and not deferred to future periods.

Costs incurred subsequent to purchase or self-construction.

Costs that are incurred subsequent to the purchase, such as those for repairs, maintenance, or betterments, are treated in one of the following ways:

-

Expensed;

-

Capitalized; or

-

Recognized by a reduction of accumulated depreciation.

Costs can be added to the carrying value of the related asset only when it is probable that future economic benefits beyond those originally anticipated for the asset will be received by the entity. For example, modifications to the asset made to extend its useful life (measured either in years or in units of potential production) or to increase its capacity (e.g., as measured by units per hour) would be capitalized. Similarly, if the expenditure results in an improved quality of output, or permits a reduction in other cost inputs (e.g., would result in labor savings), it is a candidate for capitalization. As with self-constructed assets, if the costs incurred exceed the defined threshold, they must be expensed currently.

It can usually be assumed that ordinary maintenance and repair expenditures will occur on a ratable basis over the life of the asset and should be charged to expense as incurred. Thus, if the purpose of the expenditure is either to maintain the productive capacity anticipated when the asset was acquired or constructed, or to restore it to that level, the costs are not subject to capitalization.

A partial exception is encountered if an asset is acquired in a condition that necessitates that certain expenditures be incurred in order to put it into the appropriate state for its intended use. For example, a deteriorated building may be purchased with the intention that it be restored and then utilized as a factory or office facility. In such cases, costs that otherwise would be categorized as ordinary maintenance items might be subject to capitalization, subject to the constraint that the asset not be presented at a value that exceeds its recoverable amount. Once the restoration is completed, further expenditures of similar type would be viewed as being ordinary repairs or maintenance, and thus expensed as incurred.

Extraordinary repairs.

In contrast to normal maintenance costs, extraordinary repairs or maintenance increase the value (utility) of the asset or increase the estimated useful life of the asset. Extraordinary repairs may also be referred to variously as overhauls, betterments or renewals; ultimately, it is not the term used, but the substance of what has been performed that is of most concern. There has long been widespread recognition that such expenditures can validly be used to increase the net carrying value of the asset, and that these costs are not to be immediately expensed. However, IAS 16 did not directly address this subject (it does set forth an economic benefit criterion for subsequent expenditures on plant assets already deployed), nor did it stipulate how these were to be accounted for.

Two methods of accounting for extraordinary repairs have been advocated. The more direct approach is to simply add these costs to the gross carrying value of the asset. The alternative is to reduce the previously accumulated depreciation, thereby also increasing the net book value. There is a logical basis for increasing the asset account for those repairs that increase the value of the asset, while decreasing the accumulated depreciation account for those repairs that extend the useful life of the asset. In effect, those that extend the life of the asset have "recovered" some of the depreciation previously recorded, and the asset will be depreciated again over its new, lengthier, lifetime.

While the appropriateness of these methods has yet to be addressed by the IASC, the issuance of SIC 23, Property, Plant, and Equipment—Major Inspection or Overhaul Costs, has for the first time offered official support for the concept of capitalizing extraordinary repair costs. SIC 23 states that while the costs of a major inspection or overhaul of property, plant, and equipment occurring subsequent to the acquisition of that property, plant, and equipment are generally expensed, such costs are capitalized under certain circumstances. Specifically, if the entity has already depreciated a component to reflect the consumption of benefits which are replaced or restored by the major inspection or overhaul, and the capitalized overhaul costs are identified as a separate component of the asset, then such costs can be added to the carrying value of the asset. Thus, a qualified endorsement for capitalization of overhaul (or, also, presumably extraordinary repairs and similar) costs has now been granted.

The chart on the following page summarizes the treatment of expenditures subsequent to acquisition consistent with the foregoing discussion.

Depreciation of fixed assets.

In accordance with one of the more important basic accounting concepts, the matching principle, the costs of fixed assets are allocated to the periods benefited through depreciation. Whatever the method of depreciation chosen, it must result in the systematic and rational allocation of the cost of the asset (less its residual value) over the asset's expected useful life. The determination of the useful life must take a number of factors into consideration. These factors include technological change, normal deterioration, actual physical use, and legal or other limitations on the ability to use the property. The method of depreciation is based on whether the useful life is determined as a function of time (e.g., technological change or normal deterioration) or as a function of actual physical usage.

Since depreciation accounting is intended as a strategy for cost allocation, it does not necessarily reflect changes in the value of the asset being amortized. Thus, with the exception of land, which has infinite life, all tangible fixed assets must be depreciated, even if (as sometimes occurs, particularly in periods of general price inflation) their nominal or real values increase.

Furthermore, if the recorded amount of the asset is allocated over a period of time (as opposed to units of production), it should be the expected period of usefulness to the entity, not the physical life of the property itself, that governs. Thus, such concerns as technological obsolescence, as well as normal wear and tear, must be addressed in the initial determination of the period over which to allocate the asset cost. The reporting entity's strategy for repairs and maintenance will also affect this computation, since the same physical asset might have a longer or shorter economic useful life in the hands of differing owners, depending on the care with which it is intended to be maintained.

Similarly, the same asset may have a longer or shorter economic life, depending on its intended use. A particular building, for example, may have a fifty-year expected life as a facility for storing goods or for use in light manufacturing, but as a showroom would have a shorter period of usefulness, due to the anticipated disinclination of customers to shop at enterprises housed in older premises. Again, it is not physical life, but useful economic life, that should govern.

| Type of expenditure | Characteristics | Normal accounting treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expense when incurred | Capitalize | Other | |||

| Charge to asset | Charge to accum. deprec. | ||||

|

| x | |||

| |||||

|

| ||||

| x | ||||

| x | ||||

| x | ||||

|

| ||||

| x | ||||

| x | ||||

|

| ||||

|

| ||||

|

| x | |||

| x | ||||

|

| ||||

| x | ||||

| x | ||||

Compound assets, such as buildings containing such disparate components as heating plant, roofs, and other structural elements, are most commonly recorded in several separate accounts, to facilitate the process of amortizing the different elements over varying periods. Thus, a heating plant may have an expected useful life of twenty years, the roof a life of fifteen years, and the basic structure itself a life of forty years. Recordation in separate accounts eases the calculation of periodic depreciation in such situations, although for financial reporting purposes certain of these categories might be combined, based on materiality or other considerations.

Originally, a stand-alone IAS addressed depreciation accounting. However, the guidance formerly located in that standard was absorbed by or superseded by IAS 16 for tangible long-lived assets, and IAS 38 for intangible assets. The allocation of the costs of intangibles to the periods benefited is addressed in Chapter 9. Methods of allocating the costs of tangible assets are discussed in the following section of this chapter.

Depreciation methods based on time.

-

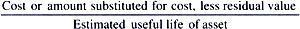

Straight-line—Depreciation expense is incurred evenly over the life of the asset. The periodic charge for depreciation is given as

-

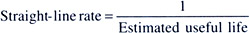

Accelerated methods—Depreciation expense is higher in the early years of the asset's useful life and lower in the later years. IAS 16 only mentions one accelerated method, the diminishing balance method, but other methods have been employed in various countries under earlier or other contemporary accounting standards.

-

Diminishing balance—A multiple of the straight-line rate times the net carrying value at the beginning of the year.

Example

Double-declining balance depreciation (if salvage value is to be recognized, stop when book value = estimated salvage value)

Depreciation = 2 x Straight-line rate x Book value at beginning of year

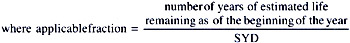

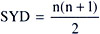

Another method to accomplish a diminishing charge for depreciation is the sum-of-the-years' digits method, that is commonly employed in the United States and certain other venues.

-

Sum-of-the-years' digits (SYD) depreciation =

(Cost less salvage value) x Applicable fraction

and

and n = estimated useful life

and n = estimated useful life

Example

An asset having a useful economic life of 5 years and no salvage value would have 5/15 (= 1/3) of its cost allocated to year 1, 4/15 to year 2, and so on.

-

-

Present value methods—A characteristic of this method of depreciation is that expense will be lower in the early years and higher in the later years. The effect of this pattern results in having the rate of return on the investment remain constant over the life of the asset. Time value of money formulas are used to effect this method of depreciation.

-

Sinking fund method—Uses the future value of an annuity formula.

-

Annuity fund method—Uses the present value of an annuity formula.

-

The present value approach is rarely encountered in practice, due to computational complexity, despite what many consider to be its theoretical validity. IAS 16 is silent regarding these methods, and the fact that the standard refers only to straight-line, diminishing balance, and sum-of-the-units methods may suggest that increasing charge methods would not be acceptable. However, the statement in IAS 16 that a "variety of depreciation methods can be used to allocate the depreciable amount of an asset on a systematic and rational basis over its useful life" would at the same time seemingly support other unnamed methods, albeit that they are not explicitly discussed in that standard. Clearly, it would be incumbent upon those choosing to employ such methods to demonstrate why these better represented the actual economic depreciation of the assets in question.

Partial-year depreciation.

Although IAS 16 is silent on the matter, when an asset is either acquired or disposed of during the year, the full year depreciation calculation should be prorated between the accounting periods involved. This is necessary to achieve proper matching. However, if individual assets in a relatively homogeneous group are regularly acquired and disposed of, one of several conventions can be adopted, as follows:

-

Record a full year's depreciation in the year of acquisition and none in the year of disposal.

-

Record one-half year's depreciation in the year of acquisition and one-half year's depreciation in the year of disposal.

Example of partial-year depreciation

Assume the following:

Taj Mahal Milling Co., a calendar-year entity, acquired a machine on June 1, 2002, that cost $40,000 with an estimated useful life of four years and a $2,500 salvage value. The depreciation expense for each full year of the asset's life is calculated as follows:

| Straight-line | Double -declining balance | Sum-of-years' digits | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | 37,500 [a] 4 = 9,375 | 50% | x | 40,000 | = | 20,000 | 4/10 | x | 37,500[a] | = | 15,000 |

| Year 2 | 9,375 | 50% | x | 20,000 | = | 10,000 | 3/10 | x | 37,500 | = | 11,250 |

| Year 3 | 9,375 | 50% | x | 10,000 | = | 5,000 | 2/10 | x | 37,500 | = | 7,500 |

| Year 4 | 9,375 | 50% | x | 5,000 | = | 2,500 | 1/10 | x | 37,500 | = | 3,750 |

|

[a]$40,000 - $2,500. | |||||||||||

Because the first full year of the asset's life does not coincide with the company's year, the amounts shown above must be prorated as follows:

| Straight-line | Double -declining balance | Sum-of-years' digits | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 7/12 x 9,375 = 5,469 | 7/12 | x | 20,000 | = | 11,667 | 7/12 | x | 15,000 | = | 8,750 |

| 2003 | 9,375 | 5/12 | x | 20,000 | - | 8,333 | 5/12 | x | 15,000 | = | 6,250 |

| 7/12 | x | 10,000 | = | 5,833 | 7/12 | x | 11,250 | = | 6,563 | ||

| 14,166 | 12,813 | ||||||||||

| 2004 | 9,375 | 5/12 | x | 10,000 | = | 4,167 | 5/12 | x | 11,250 | = | 4,687 |

| 7/12 | x | 5,000 | = | 2,917 | 7/12 | x | 7,500 | = | 4,375 | ||

| 7,084 | 9,062 | ||||||||||

| 2005 | 9,375 | 5/12 | x | 5,000 | = | 2,083 | 5/12 | x | 7,500 | = | 3,125 |

| 7/12 | x | 2,500 | = | 1,458 | 7/12 | x | 3,750 | = | 2,188 | ||

| 3,541 | 5,313 | ||||||||||

| 2006 | 5/12 x 9,375= 3,906 | 5/12 | x | 2,500 | = | 1,042 | 5/12 | x | 3,750 | = | 1,562 |

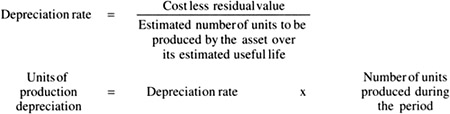

Depreciation method based on actual physical use—Sum-of-the-units (or units of production) method.

Depreciation may also be based on the number of units produced by the asset in a given year. IAS 16 identifies this as the sum-of-the-units method, but it is also commonly known as the units of production approach. It is best suited to those assets, such as machinery, that have an expected life that is most rationally defined in terms of productive output; in periods of reduced production (such as economic recession) the machinery is used less, thus extending its life when measured in units of time. It would not be rational to charge the same depreciation expense to such periods, as would be the case if straight-line or diminishing balance depreciation were used. Furthermore, if the depreciation finds its way into inventory, the unit cost in periods of reduced production would be exaggerated and could even exceed net realizable value unless a units of production approach to depreciation were taken.

Other depreciation methods.

Although IAS 16 does not discuss other methods of depreciation (nor even all the variations noted in the foregoing paragraphs), at different times and in various jurisdictions other methods have been used. Some of these are summarized as follows:

-

Retirement method— Cost of asset is expensed in period in which it is retired.

-

Replacement method— Original cost is carried in accounts and cost of replacement is expensed in the period of replacement.

-

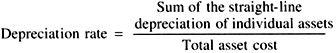

Group (or composite) method— Averages the service lives of a number of assets using a weighted-average of the units and depreciates the group or composite as if it were a single unit. A group consists of similar assets, while a composite is made up of dissimilar assets.

Depreciation expense = Depreciation rate x Total group (composite) cost

A peculiarity of the composite approach is that gains and losses are not recognized on the disposal of an asset, but rather, are netted into accumulated depreciation. This is because it is a presumption of this method that although dispositions of individual assets may yield proceeds greater than or less than their respective book values, the ultimate gross proceeds from a group of assets will not differ materially from the aggregate book value thereof, and accordingly, recognition of those individual gains or losses should be deferred and effectively netted out.

Residual value.

Most depreciation methods discussed above require that a factor be applied to the net depreciable cost of the asset, where net depreciable cost is the historical cost or amount substituted therefor (i.e., fair value) less the estimated residual value of the asset. Although residual value is often not material and in practice is frequently ignored, the concept should nonetheless be understood, particularly since it is defined differently in the context of the benchmark and allowed alternative methods described by IAS 16.

If the benchmark method (historical cost) is used, residual value is defined as the expected worth of the asset, in present dollars (i.e., without any consideration of the impact of future inflation), at the end of its useful life. Residual value should, however, be net of any expected costs of disposition. In some cases, assets will have a negative residual value, as for example when the entity must incur out-of-pocket costs to dispose of the asset, or to return the property to an earlier condition, as in the case of certain operations, such as strip mines, that are subject to environmental protection or other laws. In such instances, periodic depreciation should total more than the asset's original cost, such that at the expected disposal date, an estimated liability has been accrued equal to the negative residual value.

If the alternative (revaluation) method is elected, residual value takes on a rather different meaning. Under this scenario, residual value must be assessed anew at the date of each revaluation of the asset. This is accomplished by using data on realizable values for similar assets, ending their respective useful lives at the time of the revaluation, after having been used for purposes similar to the asset being valued. Again, no consideration can be paid to anticipated inflation, and expected future values are not to be discounted to present values to give recognition to the time value of money. As with historical cost based accounting for plant assets, if a negative residual value is anticipated, this should be effectively recognized over the useful life of the asset by charging extra depreciation, such that the estimated liability will have been accrued by the disposal date.

Choice of depreciation method.

While a number of different methods have been officially endorsed by international accounting standards, and others might be rationally supportable as well, in theory one method will be best in any given fact situation at reporting on the expiration of the service potential of the asset. Thus, straight-line presumes that the same economic value is obtained from use of the asset each period, while such accelerated approaches as the diminishing balance method are intended to combine decreasing periodic charges for depreciation with presumably increasing costs for repairs and maintenance as the asset ages, for an approximately level total cost of use across the years.

In practice, the amount of real support marshaled for the particular depreciation method employed will vary significantly, and it is very unusual for certifying (i.e., outside) accountants to dispute any entity's choice of method, as long as it is among those deemed to be GAAP. It is presumed that full disclosure of the methods used will permit the financial statement reader to interpret the financial statements meaningfully, in any event.

IAS 16 requires that the method of depreciation be critically reviewed periodically. If the expected pattern of utility of the asset has changed from when the method used was decided on, a different and more appropriate method should be selected. This change would be accounted for as a change in an accounting estimate and would affect financial reporting only on a prospective basis.

Useful lives.

Irrespective of the method of depreciation used, the estimate of useful life must be revisited periodically. Useful life is defined in terms of expected utility to the enterprise, and as such may differ from both the physical life and economic life of the asset. Useful life is affected by such things as the entity's practices regarding repairs and maintenance of its assets, as well as the pace of technological change and the market demand for goods produced and sold by the entity using the assets as productive inputs. If it is determined that the estimated life is greater or less than previously believed, the change is handled as a change in accounting estimate, not as a correction of fundamental error. Accordingly, no restatement is made to previously reported depreciation; rather, the change is accounted for strictly on a prospective basis, being reflected in the period of change and all subsequent periods.

Example of estimating the useful life

To illustrate this concept, consider an asset costing $100,000 and originally estimated to have a productive life of 10 years. The straight-line method is used, and there was no residual value anticipated. After 2 years, management revises its estimate of useful life to a total of 6 years. Since the net carrying value of the asset is $80,000 after 2 years ($100,000 x 8/10), and the remaining expected life is 4 years (2 of the 6 revised total years having already elapsed), depreciation in years 3 through 6 will be $20,000 ($80,000/4) each.

Tax methods.

The methods of computing depreciation discussed in the foregoing sections relate only to financial reporting under international accounting standards. Tax laws in different nations of the world vary widely in terms of the acceptability of depreciation methods, and it is not possible for a general treatise such as this to address those in any detail. However, to the extent that depreciation allowable for income tax reporting purposes differs from that required or permitted for financial statement purposes, deferred income taxes might have to be presented. Interperiod income tax allocation is discussed more fully in Chapter 15.

Revaluation of Fixed Assets

IAS 16 establishes two alternative approaches to accounting for fixed assets. The first of these is the benchmark treatment, under which acquisition or construction cost is used for initial recognition, subject to depreciation over the expected economic life and to possible write-down in the event of a permanent impairment in value. The allowed alternative treatment is to recognize upward revaluations.

The logic of recognizing revaluations relates to both the balance sheet and the measure of periodic performance provided by the income statement. Due to the effects of inflation (which even if quite moderate when measured on an annual basis can compound dramatically during the lengthy period over which fixed assets remain in use) the balance sheet can become a virtually meaningless agglomeration of dissimilar costs.

Furthermore, if income is determined by reference to historical costs of assets acquired in earlier periods, the replacement of those assets in the normal course of events may well require more resources than are provided by depreciation. Under these circumstances, even a nominally profitable enterprise might find that it has self-liquidated and is unable to continue in existence, at least not with the same level of productive capacity, without new debt or equity infusions. In fact, a number of enterprises in many capital-intensive industries have suffered just such a fate over the past generation.

At varying times the securities regulatory and other authorities and private sector standard setters in different nations have proposed or even required a range of alternative price level adjusted or current cost methods of accounting to address this problem. Notwithstanding these efforts, no uniform approach has ever gained the wide acceptance that would create a de facto standard. In certain jurisdictions, less complex and less useful methods have been tried to crudely compensate for the effects of inflation; accelerated depreciation methods (including 100% write-offs in the year of acquisition, in some cases) and LIFO inventory costing are the most prominent of these. Of course, these are not true substitutes for a comprehensive system of inflation-adjusted financial reporting.

Fair value.

As a practical yet reasonably effective alternative, IAS 16 promotes the concept of asset revaluation. The standard stipulates that fair value (defined as the amount for which the asset could be exchanged between knowledgeable, willing parties in an arm's-length transaction) be used in any such revaluations. Furthermore, the standard requires that, once an entity undertakes revaluations, they must continue to be made with sufficient regularity that the carrying amounts in any subsequent balance sheet are not materially at variance with then-current fair values. In other words, if the reporting entity adopts the allowed alternative treatment, it cannot report balance sheets that contain obsolete fair values, since that would not only obviate the purpose of the allowed treatment, but would actually make it impossible for the user to meaningfully interpret the financial statements.

Fair value is defined in IAS 16 as generally being the market value of assets such as land and buildings, as determined by appraisers employing normal commercial valuation techniques. Market values can also be used for machinery and equipment, but since such items often do not have readily determinable market values, particularly if intended for specialized applications, they may instead be valued at depreciated replacement cost.

Before its 1998 revision, IAS had specified that the estimated fair value of an asset was to be made in the context of the same type of service for which it has been deployed. Thus, the fair value of a factory building could only be ascertained by reference to the replacement cost or other measure of a factory building. This would be true even if, for example, the factory building being valued had alternative use as residential lofts, due to the ongoing evolution of the area in which it was sited.

Revised IAS 16 clarified the determination of fair value in such situations. Conforming to the guidance in revised IAS 22, it defines fair value as the amount at which the property would be exchanged between parties in an arm's-length transaction. Since this does not restrict the hypothetical buyer to utilize the asset in the same manner as the present owner of the property, accordingly, the operative definition of fair value is not restricted as it was previously. Fair value should be understood now to denote the amount at which the property could be exchanged, whether or not this usage would conform to that currently in effect. Fair values of land and buildings are still to be determined, in most instances, by reference to appraisals made by qualified personnel.

The logic of the change is clear. If a given property has a "higher and better" use, then current operations should bear the extra depreciation cost (if the revaluation method is used) necessitated by, in effect, underutilizing the property. This accounting could well inform owners and managers that potentially greater financial performance has been forgone due to explicit or implicit decisions which have created a suboptimal return on investment. This is precisely the sort of insight that proponents of various "current value" approaches have long held would be the benefit from dispensing with historical cost conventions.

Alternative concepts of current value.

A number of different concepts have been proposed over the years to achieve inflation accounting. Methods that address changes in specific prices, in contrast to those that attempt to adjust for general purchasing power changes, have measured reproduction cost, replacement cost, sound value, exit value, entry value, and net present value.

In brief, reproduction cost refers to the actual current cost of exactly reproducing the asset, essentially ignoring changes in technology in favor of a strict bricks-and-mortar concept. Since the same service potential could be obtained currently, in many cases, without a literal reproduction of the asset, this method fails to fully address the economic reality that accounting should ideally attempt to measure.

Replacement cost, in contrast, deals with the service potential of the asset, which is after all what truly represents value for its owner. An obvious example can be found in the realm of computers. While the cost to reproduce a particular mainframe machine exactly might be the same or somewhat lower today versus its original purchase price, the computing capacity of the machine might easily be replaced by one or a small group of microcomputers that could be obtained for a fraction of the cost of the larger machine. To gross up the balance sheet by reference to reproduction cost would be distorting, at the very least. Instead, the replacement cost of the service potential of the owned asset should be used to accomplish the revaluation contemplated by IAS 16.

Furthermore, even replacement cost, if reported on a gross basis, would be an exaggeration of the value implicit in the reporting entity's asset holdings, since the asset in question has already had some fraction of its service life expire. The concept of sound value addresses this concern. Sound value is the equivalent of the cost of replacement of the service potential of the asset, adjusted to reflect the relative loss in its utility due to the passage of time or the fraction of total productive capacity that has already been utilized.

Example of depreciated replacement cost (sound value)

An asset acquired January 1, 2001, at a cost of $40,000 was expected to have a useful economic life of 10 years. On January 1, 2004, it is appraised as having a gross replacement cost of $50,000. The sound value, or depreciated replacement cost, would be 7/10 x $50,000, or $35,000. This compares with a book, or carrying, value of $28,000 at that same date. Mechanically, to accomplish a revaluation at January 1, 2004, the asset should be written up by $10,000 (i.e., from $40,000 to $50,000 gross cost) and the accumulated depreciation should be proportionally written up by $3,000 (from $12,000 to $15,000). Under IAS 16, the net amount of the revaluation adjustment, $7,000, would be credited to revaluation surplus, an additional equity account.

An alternative accounting procedure is also permitted by the standard, under which the accumulated depreciation at the date of the revaluation is written off against the gross carrying value of the asset. In the foregoing example, this would mean that the $12,000 of accumulated depreciation at January 1, 2004, immediately prior to the revaluation, would be credited to the gross asset amount, $40,000, thereby reducing it to $28,000. Then the asset account would be adjusted to reflect the valuation of $35,000 by increasing the asset account by $7,000 ($35,000 - $28,000), with the offset again in stockholders' equity. In terms of total assets reported in the balance sheet, this has exactly the same effect as the first method.

However, many users of financial statements, including credit grantors and prospective investors, pay heed to the ratio of net property and equipment as a fraction of the related gross amounts. This is done to assess the relative age of the enterprise's productive assets and, indirectly, to estimate the timing and amounts of cash needs for asset replacements. There is a significant diminution of information under the second method. Accordingly, the first approach described above, preserving the relationship between gross and net asset amounts after the revaluation, is recommended as being the preferable alternative if the goal is meaningful financial reporting.

Application of revaluation to all assets in class.

IAS 16 prudently requires that if any assets are revalued, all other assets in those groupings or categories also be revalued. This is necessary to avert the presentation of a balance sheet that contains an unintelligible mixture of historical costs and current values. Coupled with the requirement that revaluations take place with sufficient frequency to approximate fair values as of each balance sheet date, this preserves the integrity of the financial reporting process. In fact, given that a balance sheet prepared under the benchmark method of historical cost will, in fact, contain different historical costs (due to assets being acquired at varying times using dollars having different general and specific purchasing powers) the allowable alternative approach has the promise of providing even more consistent financial reporting. Offsetting this potential improvement somewhat, of course, is the greater subjectivity applied in determining fair values, vs. actual historical costs.

Although the requirement of IAS 16 is to revalue all assets in a given class, the standard recognizes that it may be more practical to accomplish this on a rolling, or cycle, basis. This would be done by revaluing one-third of the assets in a given asset category, such as machinery, in each year, so that as of any balance sheet date one-third of the group is valued at current fair value, another one-third is valued at amounts that are one year obsolete, and another one-third are valued at amounts that are two years obsolete. Unless values are changing rapidly, it is likely that the balance sheet would not be materially distorted, and therefore, this approach would in all likelihood be a reasonable means to facilitate the revaluation process.

Revaluation adjustments taken into income.

While, in general, revaluation adjustments are to be shown directly in stockholders' equity as revaluation surplus, if a downward adjustment had previously been made to the asset and was recognized as an expense, the later upward revaluation would also be reported as income. Any revaluation receiving this treatment would be limited to the amount of expense recognized previously. As a practical matter this should be a rare occurrence, since if the asset was revalued downward, the reference for that measurement would have been the estimated recoverable amount, and given what was judged to be a permanent impairment at an earlier date, it is very unlikely that there could be a later upward revaluation that could recover more than a minor portion of that impairment. However, in these unusual situations, a gain would be taken through the income statement.

The converse of the foregoing is also true: If an asset's carrying amount is decreased by recognition of a permanent impairment, but the asset had previously been revalued upward by crediting revaluation surplus, the decline should be reported as a reduction of that surplus account rather than being reported as income. Any decline in value in excess of the amount previously recognized as an upward revaluation should be reported in earnings currently.

Under the provisions of IAS 16, the amount credited to revaluation surplus can either be amortized to retained earnings (but not through the income statement!) as the asset is being depreciated, or it can be held in the surplus account until such time as the asset is disposed of or retired from service. In the example below, periodic amortization is utilized.

Example of revaluation and later downward adjustment

Consider the following example to illustrate the foregoing:

An asset was acquired January 1, 2001, for $10,000 and is expected to have a 5-year life. Straight-line depreciation will be used. At January 1, 2003, the asset is appraised as having a sound value (depreciated replacement cost) of $9,000. On January 1, 2005, the asset is appraised at a sound value of $1,500. The entries to reflect these events are as follows:

| 1/1/01 | Asset | 10,000 | |

| 10,000 | ||

| 12/31/01 | Depreciation expense | 2,000 | |

| 2,000 | ||

| 12/31/02 | Depreciation expense | 2,000 | |

| 2,000 | ||

| 1/1/03 | Asset | 5,000 | |

| 2,000 | ||

| 3,000 | ||

| 12/31/03 | Depreciation expense | 3,000 | |

| 3,000 | ||

| Revaluation surplus | 1,000 | ||

| 1,000 | ||

| 12/31/04 | Depreciation expense | 3,000 | |

| 3,000 | ||

| Revaluation surplus | 1,000 | ||

| 1,000 | ||

| 1/1/05 | Accumulated depreciation | 6,000 | |

| Revaluation surplus | 1,000 | ||

| Loss from asset impairment | 500 | ||

| 7,500 |

Certain of the entries in the foregoing example may need elaboration. The entries at 2001 and 2002 year-ends are to record depreciation based on original cost, since there had been no revaluations through that point in time. On January 1, 2003, the revaluation is recorded; the appraisal of sound value ($9,000) suggests a 50% increase in value over depreciated historical cost ($6,000), which in turn means that the gross asset should be written up to $15,000 (a 50% increase over the historical cost, $10,000) and the accumulated depreciation should be written up proportionately (from $4,000 to $6,000). Had the appraisal revealed that the useful life of the equipment had also changed from its originally estimated amount, that would have been dealt with prospectively, as prescribed by IAS 8 (see Chapter 21 for a discussion of this matter).

In 2003 and 2004, depreciation must be provided on the new higher value recorded at the beginning of 2003 (assuming that no additional appraisal is obtained in 2004). Since the asset has been written up by 50%, the periodic charge for depreciation must reflect the higher cost of doing business. However, while the income statements in each year must absorb greater depreciation expense, within the equity section of the balance sheet there will be an offsetting adjustment to transfer revaluation surplus to retained earnings, in the amount of the extra depreciation recognized each year.

As of January 1, 2005, the book value of the equipment is $3,000, which reflects the fact that the asset, having a gross replacement cost when last appraised of $15,000, is now 80% used up. A new appraisal reveals that the fair value is only $1,500 at this time. However, rather than charging the $1,500 decline in value ($3,000 - $1,500) to income, the portion of the decline that represents a retracing of the value increase previously recognized should be accounted for as a reversal of the revaluation surplus, not as a realized loss.

To effect the foregoing, the gross asset and related accumulated depreciation should be written down from amounts based on the 2003 appraisal (updated, in the case of accumulated depreciation, to the current balance) to original cost. Thus, the asset should be written down from $15,000 to $10,000, and the accumulated depreciation adjusted downward from $12,000 to $8,000. The further reduction in book value (from $2,000 to $1,500, as indicated by the latest appraisal) will be taken into income as a realized loss. The offset will be to accumulated depreciation, since the decline in value effectively means that the amount recognized as depreciation in prior periods had been understated; assuming no change in useful life, the depreciation charge for the final year (2005) will be $1,500, reducing the book value to zero at year-end.

Exchanges of assets.

IAS 16 discusses the accounting to be applied to those situations in which assets are exchanged for other similar or dissimilar assets, with or without the additional consideration of monetary assets. This topic is addressed later in this chapter, under the heading "Nonmonetary (Exchange) Transactions."

Revisions to estimated residual value.

Under the benchmark treatment prescribed by IAS 16, the amount estimated for residual value is made at the date of acquisition (or date a self-constructed asset is placed in service) and is not revised subsequently. In this regard the international standard departs from what has been the common practice of treating changes in estimated residual or salvage value as a change in an accounting estimate, and accounting for it prospectively by altering the annual depreciation charge for later years.

If the allowable alternative treatment is elected, at the date of each revaluation of the asset the expected residual amount should also be reassessed. The standard suggests that reference be made to actual residual values of similar assets reaching the end of their useful economic lives about the time the reevaluation is being conducted.

Deferred tax effects of revaluations.

As described in great detail in Chapter 15, the tax effects of temporary differences must be provided for by the process commonly referred to as deferred tax accounting. Thus, if depreciable plant assets are depreciated over longer lives for financial reporting purposes than for tax reporting purposes, a deferred tax liability will be created in the early years and then drawn down in later years. Generally speaking, the deferred tax provided will be measured by the expected future tax rate applied to the temporary difference at the time it reverses; unless future tax rate changes have already been enacted, the current rate structure is used as an unbiased estimator of those future effects.

In the case of revaluation of plant assets, it will almost universally be true that taxing authorities will not permit the higher revalued amounts to be depreciated for purposes of computing tax liabilities. Instead, only the actual cost incurred can be used to offset tax obligations. On the other hand, since revaluations are intended to reflect actual current fair values or values in use, they do portend that taxes will be imposed at some future date, typically when the assets are disposed of at gains (when measured against historical costs). Accordingly, a deferred tax liability is still required to be recognized, even though it does not relate to temporary differences arising from periodic depreciation charges.

The IASC's Standing Interpretation Committee has confirmed, in SIC 21, that measurement of the deferred tax effects relating to the revaluation of nondepreciable assets must be made with reference to the tax consequences that would follow from recovery of the carrying amount of that asset through an eventual sale. This is necessary because the asset will not be depreciated, and hence, no part of its carrying amount is considered to be recovered through use. As a practical matter this means that if there are differential capital gain and ordinary income tax rates, deferred taxes will be computed with reference to the former.

Impairment of Tangible Long-Lived Assets

Until the promulgation of IAS 36, Impairment of Assets, there was very limited guidance available under international accounting standards to deal with the possible diminution in value that might be associated with long-lived assets. It had long been established under various national accounting standards that permanent impairments (sometimes called "other than temporary" impairments) in long-lived assets necessitated write-downs in carrying values, but in general the two critical questions—when to test for impairment and how to measure it—were left unaddressed. IAS 16 did state that property, plant, and equipment items should be periodically reviewed for possible impairment—defined as having occurred when an asset's recoverable amount fell below its carrying value. While some reporting enterprises undoubtedly did apply the spirit as well as the letter of IAS 16, particularly when a significant event had occurred which made economic viability of major assets an obvious issue, in general, the lack of specific guidance more likely was an impediment to application of the impairment requirements of that standard. Now, however, with a comprehensive standard, the process of considering impairments will be greatly facilitated.

Principal requirements of IAS 36.

The standard on impairment requires that the recoverable amount of tangible (and intangible—discussed in the following chapter) long-lived assets be estimated, for purpose of identifying and measuring impairments, whenever there are indications that such a circumstance might exist. There is no fixed requirement to make this determination on a regular schedule (as there is for certain intangible assets), but a fairly extensive set of criteria is included in IAS 36 to assist entities in making the determination of when such a review might be warranted. If an asset or a group of assets which comprise what is now called a "cash generating unit" is found to be impaired, which means that the carrying amount exceeds the net recoverable amount as determined by reference to net selling prices and value in use, a write-down is required. Thus, IAS 36 responds to the two key questions that, because they were heretofore left unanswered, made it difficult to formally address impairment concerns.

Impairment is defined as the excess of carrying value over recoverable amount; recoverable amount is the greater of net selling price or value in use. Net selling price is essentially fair value less costs of disposal (i.e., what would be netted by the entity in an arm's-length transaction, or what is sometimes referred to as "exit value") and value in use is most commonly defined as the net present value of future cash flows associated with the asset or group of assets. Under different circumstances, it may be more or less difficult to obtain these data, but IAS 36 offers sufficient guidance to deal with most situations likely to be encountered in practice.

When it is determined that an asset (or cash generating unit) has indeed been impaired, IAS 36 requires that its carrying value be reduced. Any decline in value is recognized currently in income, for assets accounted for by the benchmark (amortized historical cost) method as set forth in IAS 16. Declines affecting assets accounted for by the allowed alternative (revaluation) method are recognized in the revaluation (stockholders' equity) account. Recoveries in value, not to exceed pre-impairment carrying value, are also given recognition, consistent with the accounting applied to the decline in value.

Identifying impairments.

According to IAS 36, at each financial reporting date the reporting entity should determine whether there are conditions that would indicate that impairments may have occurred. Note that this is not a requirement that possible impairments be calculated for all assets at each balance sheet date, which would be a formidable undertaking for most enterprises. Rather, it is the existence of conditions that might be suggestive of a heightened risk of impairment that must be evaluated. However, if such indicators are present, then further analysis will be necessary.

The standard provides a set of indicators of potential impairment and suggests that these represent a minimum array of factors to be given consideration. Other more industry- or entity-specific gauges can and should be devised and employed by the reporting enterprise, particularly when the more general indicators are found over time to be less sensitive than is deemed desirable. As experience with IAS 36 is gained, it is likely that more tailored indicators will evolve for some industries.

At a minimum, the following external and internal signs of possible impairment are to be given consideration on an annual basis:

-

Market value declines for specific assets or cash generating units, beyond the declines expected as a function of asset aging and use;

-

Significant changes in the technological, market, economic, or legal environments in which the enterprise operates, or the specific market to which the asset is dedicated;

-

Increases in the market interest rate or other market-oriented rate of return such that increases in the discount rate to be employed in determining value in use can be anticipated, with a resultant enhanced likelihood that impairments will emerge;

-

Declines in the (publicly owned) entity's market capitalization suggest that the aggregate carrying value of assets exceeds the perceived value of the enterprise taken as a whole;

-

There is specific evidence of obsolescence or of physical damage to an asset or group of assets;

-

There have been significant internal changes to the organization or its operations, such as product discontinuation decisions or restructurings, so that the expected remaining useful life or utility of the asset has seemingly been reduced; and

-

Internal reporting data suggest that the economic performance of the asset or group of assets is, or will become, worse than previously anticipated.

The indicators which are derived from information internally generated by the reporting entity are the more difficult to interpret, and also the ones which, should it be so inclined to do so, may be subject to greater obfuscation by the entity. Information such as the cash flows being generated by an asset or group of assets, or the future cash needs to operate or maintain the asset, for example, may be rather subjective and not immediately apparent. Some of the information is likely to only be accessible "off-line" (i.e., from budgets and forecasts, rather than from the entity's actual accounting system) and thus may lack the credibility of historical data. Finally, the financial performance of individual assets will almost never be ascertainable even from historical accounting records, and the minimum level of aggregation of bookkeeping information will almost always be higher than the level required by IAS 36 (discussed below). Thus, in practical terms, there will be many instances in which there are at best only vague intimations of impairment, and whether further corroborating or disconfirming data is sought out will be a matter of judgment.

The mere fact that one or more of the foregoing indicators suggests that there might be cause for concern about possible asset impairment does not necessarily imply that formal impairment testing must proceed. For example, as noted in IAS 36, an increase in the market rate of interest would not trigger a formal impairment evaluation if either (1) the relevant discount rate to be applied in the determination of the value in use of an asset (via the present value of future net cash flows) would not be expected to track the general changes in market rates of interest, or (2) the effects of changes in the discount rate, tracking changes in market rates of interest, would tend to be offset by other changes in future cash flow, as when an entity has a history of adjusting revenues (and thus cash inflows) to compensate for interest rate rises. However, in the absence of a plausible explanation of why the signals of possible impairment should not be further considered, the implication is that the presence of one or more of these would necessitate some follow-up investigation.

Computing recoverable amounts—General concepts.

IAS 36 defines impairment as the excess of carrying value over recoverable amount, and goes on to define recoverable amount as the greater of two alternative measures, net selling price and value in use. The objective is to recognize an impairment only when the economic value of an asset (or cash generating unit consisting of a group of assets) is truly below its book (carrying) value. In theory, and for the most part in practice also, an entity making rational choices would sell an asset if its net selling price (fair value less costs of disposal) were greater than the asset's value in use, and would continue to employ the asset if value in use exceeded salvage value. Thus, the economic value of an asset is most meaningfully measured with reference to the greater of these two amounts, since the entity will retain or dispose of the asset consistent with what appears to be its highest and best use. Once recoverable amount has been determined, this is to be compared to carrying value; if recoverable amount is lower, the asset has been impaired, and under the new rules this impairment must be given accounting recognition.

Determining net selling prices.

While the concept of recoverable amount has a clear meaning, the actual determination of both the net selling price and the value in use of the asset being evaluated will typically present some difficulties. For actively traded assets, net selling price can be ascertained by reference to publicly available information (e.g., from price lists or dealer quotations), and costs of disposal will either be implicitly factored into those amounts (such as when a dealer quote includes pick-up, shipping, etc.) or can be readily estimated. Most productive tangible assets, such as machinery and equipment, will not be easily priced in active markets, however. While IAS 36 offers only limited guidance for such situations, it is clear that it will often be necessary to reason by analogy (i.e., to draw inferences from recent transactions in similar assets), making adjustments for age, condition, productive capacity, and other variables. In many industries, trade publications and other data sources can provide a great deal of insight into the market value of key assets, and if there is a sincere effort to tap into these resources, much could be accomplished. On the other hand, some work will be required and it is not difficult to imagine that there may be reluctance to undertake this, although an entity's ability to claim compliance with IAS will encourage it to do so.

Despite the concerns noted above, the difficulties in identifying net selling prices should not be overstated. Experience with SFAS 144, the US GAAP requirement for determining, measuring, and reporting on asset impairments (which replaced the earlier, but very similar, SFAS 121), suggests that there is a wealth of information to be used. In this era of Internet access and vast amounts of published industry data, from both governmental and private sources, estimating net selling prices for a wide range of productive assets should be quite feasible. Furthermore, in many nations for which persistent inflation has been a problem for decades, some form of inflation-adjusted financial reporting may have been practiced, as indeed it was for a period in both the US and the UK, and that experience taught many corporate and public accountants how to develop similar information. Finally, in many (perhaps most) cases, there will either be no signs of possible impairment, in which case no effort to compute recoverable amounts will be needed, or despite one or more indicators of possible impairment the asset's value in use will clearly exceed carrying amount, thus dispensing with any need to measure impairment.

Computing value in use.

The second component of recoverable amount is value in use, and when there are indicators of impairment and no clear evidence that either net selling price or value in use exceed carrying value, then value in use will often need to be estimated. The computation of value in use involves a two-step process: first, future cash flows must be estimated; and second, the present value of these cash flows must be calculated by application of an appropriate discount rate. These will be discussed in turn in the following paragraphs.

Projection of future cash flows must be based on reasonable assumptions; exaggerated revenue growth rates, significant anticipated cost reductions, or unreasonable useful lives for plant assets must be avoided. In general, recent past experience is a fair guide to the near-term future, but a recent growth spurt should not be extrapolated to more than the near-term future. Industry patterns as well as the experiences of the entity itself usually must be considered, since no single company, no matter how well managed or fortunate, can long escape from the implications of industry or economy-wide trends. For example, consider an entity which produces goods that are becoming, or are reasonably forecast to become, obsolete, but which are currently quite profitable. Given these facts, a limited horizon of usefulness should be imposed upon the equipment used for the production of these goods, which might imply an impairment should be recognized.

Typically, extrapolation to future periods cannot exceed the amount of "base period" data upon which the projection is built. Thus, a five-year projection, to be mathematically sound, must be based on at least five years of actual historical performance data. Also, since no business can exponentially grow forever, even if, for example, a five-year historical analysis suggests a 20% annual (inflation adjusted) growth rate, beyond a horizon of two years, a moderation of that growth must be hypothesized. This is even more true for a single asset or small cash generating unit, since physical constraints and the ironclad law of diminishing marginal returns makes it virtually inevitable that a plateau will be reached, beyond which further growth will be tightly constrained. If exceptional returns are being reaped from the assets used to produce a product line, competitors will enter the market and ultimately this, too, will restrict future cash flows.

For purposes of determining value in use, cash flow projections must represent management's best estimate, not its most optimistic view of the future. Externally sourced data is considered to be more valid than purely internal information. To the extent that internal sources such as budgets and forecasts are employed, these will have greater probative value if they have been reviewed and approved by upper levels of management, and if similar budgets and forecasts used in prior periods have been shown to be accurate. More modest assumptions should be made when projecting beyond the periods covered in the formally prepared and reviewed budgets, since not only are estimates about the future inherently less reliable as the horizon is extended, but also the absence of a formal budgeting process regarding the "out years" reduces the credibility of any such projections.

IAS 36 stipulates that steady or declining growth rates must be utilized for periods beyond those covered by the most recent budgets and forecasts. It further states that, barring an ability to demonstrate why a higher rate is appropriate, the growth rate should not exceed the long-term growth rate of the industry in which the entity participates.

Finally, with regard to cash flow projections, it is clear that projections for a period longer than the asset's remaining depreciable life would not be credible. Since the cost of tangible long-lived assets should be rationally allocated over their useful lives, it is implicitly management's representation that no cash flows will occur after the estimated lives are completed. On the other hand, an insistence that there will be work produced by the asset after its nominal terminal date would imply that IAS governing depreciation accounting was not conformed with.

With reference to cash flow projections, the guidance offered by IAS 36 suggests that only normal, recurring cash inflows from the continuing use of the asset being evaluated should be considered, plus the estimated salvage value at the end of its useful life, if any. Cash outflows needed to generate the cash inflows must also be included in the analysis, including any cash outflows needed to prepare the asset for its intended productive use. Noncash costs, such as depreciation of the asset, obviously must be excluded, inasmuch as these do not affect cash flows, and in the case of depreciation, this would in effect "double count" the very thing being measured. Projections should always exclude cash flows related to financing the asset, for example, interest and principal repayments on any debt incurred in acquiring the asset, since operating decisions (e.g., keeping or disposing of an asset) are separate from financing decisions (borrowing, leasing, buying with equity capital funds). Also, cash flow projections must pertain to the asset that exists and is in use, not to hypothetical future assets or assets currently in use but to be value enhanced by later overhauls or redesigns. Income tax effects are also to be disregarded (i.e., the entire analysis should be on a pretax basis).

The need to identify specific cash flows is the reason why an asset-by-asset approach will most often be ineffective or impossible to perform, since few individual assets have identifiable cash flows. For example, a factory which employs dozens of drill presses, lathes, grinding machines, and other related types of equipment to produce precision components for the automobile industry cannot possibly identify the contribution to cash flow made by a given drill press. For this reason, IAS 36 has developed the concept of the "cash generating unit."

Cash generating units.

Under IAS 36, when cash flows cannot be identified with individual assets, these may need to be grouped in order to conduct an impairment test. The requirement is that this grouping be performed at the lowest level possible, which would be the smallest aggregation of assets for which discrete cash flows can be identified, and which are independent of other groups of assets. In practice, this may be a department, a product line, or a factory, for which the output of product and the input of raw materials, labor, and overhead can be identified. While the precise contribution to overall cash flow made by a given drill press may be impossible to surmise, the cash inflows and outflows of a department which produces and sells a discrete product line to an identified group of customers can be readily determined.

An obvious temptation would be to essentially aggregate the entire enterprise into a single cash generating unit, arguing perhaps that it represents an integrated operation. While in some instances this may be correct, in most cases it will not. The risk in too-generously aggregating long-lived assets into cash generating units is that many possible impairments will be concealed, as the subunits having recoverable amounts in excess of carrying amounts will offset those having the opposite circumstance. In this, the effect is identical to applying lower of cost or market to the aggregate inventory of an entity, rather than to component groups or to each inventory item taken by itself. Thus IAS 36 is clear that care must be exercised to be sure that all aggregation is conducted at the lowest feasible level.

Some expansion of the aggregation process will become necessary when an entity's operations are vertically integrated. IAS 36 provides one such example of a mining enterprise which has a private railway to haul its ore; since the railway has no external customers and thus no independent cash inflows, impairment can only be assessed by grouping the mine and the railway into a single cash generating unit. Another such example is a bus line that is a contract provider to a municipality; evaluation of subunits, such as individual bus routes, is not feasible since the contractual arrangement precludes taking individual decisions, such as discontinuing service, regarding any single route. IAS 36 requires that cash generating units be defined consistently from period to period.

Discount rate.

The other part of the challenge in computing value in use comes from identifying the appropriate discount rate to apply to projected future cash flows. There are actually two key issues to address. The first is to determine an appropriate rate, ignoring inflation effects. IAS 36 stipulates that a risk rate must be used which is pertinent to the type of asset being valued. Thus, arguably at least, the discount rate to be applied to projected cash flows relating to a steel mill might be somewhat lower than that used to compute the present value of cash flows arising from the use of a piece of high-technology equipment, since the latter may be subject to far greater risk of sudden, unanticipated obsolescence than the former. This concept is supported by market data, which prices debt offerings by entities in riskier industries at higher yields than those in more stable industries.

IAS 36 suggests that identifying the appropriate risk-adjusted cost of capital to employ as a discount rate can be accomplished by reference to the implicit rates in current market transactions (e.g., leasing transactions), or from the weighted-average cost of capital of publicly traded enterprises in the same industry grouping. There are such statistics available in many markets, and the entity's own recent transactions, typically in leasing or borrowing to buy other long-lived assets, will be highly salient information.

When risk-adjusted rates are not available, however, it will become necessary to develop a rate from surrogate data. The two aspects of this are to (1) identify the pure time value of money for the requisite time horizon over which the asset will be utilized—short term almost always carrying a lower rate than intermediate or long term; and (2) to add an appropriate risk premium to the pure interest factor, which is related to the variability of future cash flows, with greater variability (the technical definition of risk) being associated with higher risk premiums. Of these two tasks, the latter is likely to prove the more difficult in practice. IAS 36 provides a fairly extended discussion of the methodology to utilize, however, addressing such factors as country risk, currency risk, cash flow risk, and pricing risk. As with all aspects of the impairment analysis, this must be done on a pretax basis and is independent of any considerations regarding how the asset was financed.

The second aspect of determining an appropriate discount rate is somewhat more subtle than that discussed above. The rate used must either be inflation-adjusted or inflation-unadjusted, consistent with how the future cash flows were determined. If the future cash flows were developed in nominal currency units, and if (as has often been true, although for much of the developed world less so now than for any time over the past generation) there is an expectation that prices will inflate over time, future cash inflows and outflows will be projected to grow even if input and output factors will remain constant. If nominal currency units are used, thus inflating the gross amounts and net cash flows increasingly over the years due to the compounding effect of annual inflation assumptions, the discount rate must be similarly increased.

On the other hand, if future cash inflows and outflows are projected in real currency units, the appropriate discount rate will be a lower, inflation-unadjusted rate. If consistent assumptions are used for cash flows and the discount rate, the net result, that is, the present value of future cash flows, will be identical, and thus either approach, if properly applied, is acceptable. The practical risk is that in performing the analyses inconsistent assumptions will be made, thus making the results of little worth.