Concepts, Rules, and Examples

Construction contract revenue may be recognized during construction rather than at the completion of the contract. This "as earned" approach to revenue recognition is justified because under most long-term construction contracts, both the buyer and the seller (contractor) obtain enforceable rights. The buyer has the legal right to require specific performance from the contractor and, in effect, has an ownership claim to the contractor's work in progress. The contractor, under most long-term contracts, has the right to require the buyer to make progress payments during the construction period. The substance of this business activity is that a continuous sale occurs as the work progresses.

IAS 11 recognizes the percentage-of-completion method as the only valid method of accounting for construction contracts. Prior to the 1993 revision of IAS 11, both the percentage-of-completion method and the completed-contract method were recognized as being acceptable alternative methods of accounting for long-term construction activities.

The thinking worldwide on this issue is equivocal and rather confusing. Many countries still recognize both the foregoing methods as being in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), although they may not be viewed as equally acceptable under given circumstances. The United States, Canada, and Japan are usually noted as protagonists of both GAAP methods on this subject. There is another set of countries whose GAAP is in line with the current IAS on the subject. The national accounting standards of the United Kingdom, Australia, China, and New Zealand recognize only the percentage-of-completion method. Germany, on the other hand, seems to have taken the extreme viewpoint as a supporter of only the completed-contract method. Although it may seem that the world is completely divided on this matter, a closer look into this contentious issue offers a better insight into the diversity in approaches.

Although Germany seems to be alone in the contest of alternative methods of accounting for long-term contracts, its position is more explicable when it is recalled that this country has traditionally been known for its conservative approach and its emphasis on creditor protection. Thus, it seems to have been guided primarily by the prudence concept in developing this accounting principle.

For countries that support both the methods, it is well known that some also express a clear preference for the percentage-of-completion method. US GAAP, for instance, exemplifies this position. It recommends the percentage-of-completion method as preferable when estimates are reasonably dependable and the following conditions exist:

-

Contracts executed by the parties normally include provisions that clearly specify the enforceable rights regarding goods or services to be provided and received by the parties, the consideration to be exchanged, and the manner and terms of settlement.

-

The buyer can be expected to satisfy its obligations under the contract.

-

The contractor can be expected to perform its contractual obligations.

The Accounting Standards Division of the AICPA believes that these two methods should not be used as acceptable alternatives for the same set of circumstances. US GAAP states that, in general, when estimates of costs to complete and extent of progress toward completion of long-term contracts are reasonably dependable, the percentage-of-completion method is preferable. When lack of dependable estimates or inherent hazards cause forecasts to be doubtful, the completed-contract method is preferable.

Percentage-of-Completion Method in Detail

A number of controversial issues are encountered when the percentage-of-completion method is used in practice. In the following paragraphs, the authors' address a number of these, offering proposed approaches to follow for those matters that have not been authoritatively resolved, or in many instances, even discussed by the international accounting standards.

IAS 11 defines the percentage-of-completion method as follows:

-

The percentage of completion method recognizes income as work on a contract (or group of closely related contracts) progresses. The recognition of revenues and expenses is generally based on the stage of completion of the contract(s), except when a loss is expected, in which case immediate recognition of the loss is called (irrespective of the stage of completion). Under this method contract revenue is matched with the contract costs incurred in reaching the stage of completion, resulting in the reporting of contract revenue, contract costs and profit based on proportion of work completed.

Under the percentage-of-completion method, the construction-in-progress (CIP) account is used to accumulate costs and recognized income. When the CIP exceeds billings, the difference is reported as a current asset. If billings exceed CIP, the difference is reported as a current liability. Where more than one contract exists, the excess cost or liability should be determined on a project-by-project basis, with the accumulated costs and liabilities being stated separately on the balance sheet. Assets and liabilities should not be offset unless a right of offset exists. Thus, the net debit balances for certain contracts should not ordinarily be offset against net credit balances for other contracts. An exception may exist if the balances relate to contracts that meet the criteria for combining.

Under the percentage-of-completion method, income should not be based on advances (cash collections) or progress (interim) billings. Cash collections and interim billings are based on contract terms that do not necessarily measure contract performance.

Costs and estimated earnings in excess of billings should be classified as an asset. If billings exceed costs and estimated earnings, the difference should be classified as a liability.

Contract costs.

Contract costs comprise costs that are identifiable with a specific contract, plus those that are attributable to contracting activity in general and can be allocated to the contract and those that are contractually chargeable to a customer. Generally, contract costs would include all direct costs, such as direct materials, direct labor, and direct expenses and any construction overhead that could specifically be allocated to specific contracts.

Direct costs or costs that are identifiable with a specific contract include

-

Costs of materials consumed in the specific construction contract

-

Wages and other labor costs for site labor and site supervisors

-

Depreciation charges of plant and equipment used in the contract

-

Lease rentals of hired plant and equipment specifically for the contract

-

Cost incurred in shifting of plant, equipment, and materials to and from the construction site

-

Cost of design and technical assistance directly identifiable with a specific contract

-

Estimated costs of any work undertaken under a warranty or guarantee

-

Claims from third parties

With regard to claims from third parties, these should be accrued if they rise to the level of "provisions" as defined by recently promulgated standard IAS 37 (which corresponds to "probable" contingencies under the now obsolete standard IAS 10). This requires that an obligation exists at the balance sheet date that is subject to reasonable measurement. However, if either of the above mentioned conditions is not met (and the possibility of the loss is not remote), this contingency will only be disclosed. Contingent losses are specifically required to be disclosed under IAS 11.

Contract costs may be reduced by incidental income if such income is not included in contract revenue. For instance, sale proceeds (net of any selling expenses) from the disposal of any surplus materials or from the sale of plant and equipment at the end of the contract may be credited or offset against these expenses. Drawing an analogy from this principle, it could be argued that if advances received from customers are invested by the contractor temporarily (instead of being allowed to lie idle in a current account), any interest earned on such investments could be treated as incidental income and used in reducing contract costs, which may or may not include borrowing costs (depending on how the contractor is financed, whether self-financed or leveraged). On the other hand, it may also be argued that instead of being subtracted from contract costs, such interest income should be added to contract revenue.

In the authors' opinion, the latter argument may be valid if the contract is structured in such a manner that the contractor receives lump-sum advances at the beginning of the contract (or for that matter, even during the term of the contract, such that the advances at any point in time exceed the amounts due the contractor from the customer). In these cases, such interest income should, in fact, be treated as contract revenue and not offset against contract costs. The reasoning underlying treating this differently from the earlier instance (where idle funds resulting from advances are invested temporarily) is that such advances were envisioned by the terms of the contract and as such were probably fully considered in the negotiation process that preceded fixing contract revenue. Thus, since negotiated as part of the total contract price, this belongs in contract revenues. (It should be borne in mind that the different treatments for interest income will in fact have a bearing on the determination of the percentage or stage of completion of a construction contract.)

Indirect costs or overhead expenses should be included in contract costs provided that they are attributable to the contracting activity in general and could be allocated to specific contracts. Such costs include construction overhead, cost of insurance, cost of design, and technical assistance that is not related directly to specific contracts. They should be allocated using methods that are systematic and rational and are applied in a consistent manner to costs having similar features or characteristics. The allocation should be based on the normal level of construction activity, not on theoretical maximum capacity.

Example of contract costs

A construction company incurs $700,000 in annual rental expense for the office space occupied by a group of engineers and architects and their support staff. The company utilizes this group to act as the quality assurance team that overlooks all contracts undertaken by the company. The company also incurs in the aggregate another $300,000 as the annual expenditure toward electricity, water, and maintenance of this office space occupied by the group. Since the group is responsible for quality assurance for all contracts on hand, its work, by nature, cannot be considered as being directed toward any specific contract but is in support of the entire contracting activity. Thus, the company should allocate the rent expense and the cost of utilities in accordance with a systematic and rational basis of allocation, which should be applied consistently to both types of expenditure (since they have similar characteristics).

Although the bases of allocation of this construction overhead could be many (such as the amounts of contract revenue, contract costs, and labor hours utilized in each contract) the basis of allocation that seems most rational is contract revenue. Further, since both expenses are similar in nature, allocating both the costs on the basis of the amount of contract revenue generated by each construction contract would also satisfy the consistency criteria.

Other examples of construction overhead or costs that should be allocated to contract costs are

-

Costs of preparing and processing payroll of employees engaged in construction activity

-

Borrowing costs that are capitalized under IAS 23 in conformity with the allowed alternative treatment

Certain costs are specifically excluded from allocation to the construction contract, as the standard considers them as not attributable to the construction activity. Such costs may include

-

General and administrative costs that are not contractually reimbursable

-

Costs incurred in marketing or selling

-

Research and development costs that are not contractually reimbursable

-

Depreciation of plant and equipment that is lying idle and not used in any particular contract

Types of contract costs.

Contract costs can be broken down into two categories: costs incurred to date and estimated costs to complete. The costs incurred to date include precontract costs and costs incurred after contract acceptance. Precontract costs are costs incurred before a contract has been entered into, with the expectation that the contract will be accepted and these costs will thereby be recoverable through billings. The criteria for recognition of such costs are

-

They are capable of being identified separately.

-

They can be measured reliably.

-

It is probable that the contract will be obtained.

Precontract costs include costs of architectural designs, costs of learning a new process, cost of securing the contract, and any other costs that are expected to be recovered if the contract is accepted. Contract costs incurred after the acceptance of the contract are costs incurred toward the completion of the project and are also capitalized in the construction-in-progress (CIP) account. The contract does not have to be identified before the capitalization decision is made; it is only necessary that there be an expectation of the recovery of the costs. Once the contract has been accepted, the precontract costs become contract costs incurred to date. However, if the precontract costs are already recognized as an expense in the period in which they are incurred, they are not included in contract costs when the contract is obtained in a subsequent period.

Estimated costs to complete.

These are the anticipated costs required to complete a project at a scheduled time. They would be comprised of the same elements as the original total estimated contract costs and would be based on prices expected to be in effect when the costs are incurred. The latest estimates should be used to determine the progress toward completion.

Although IAS 11 does not specifically provide instructions for estimating costs to complete, practical guidance can be gleaned from other international accounting standards, as follows: The first rule is that systematic and consistent procedures should be used. These procedures should be correlated with the cost accounting system and should be able to provide a comparison between actual and estimated costs. Additionally, the determination of estimated total contract costs should identify the significant cost elements.

A second important point is that the estimation of the costs to complete should include the same elements of costs included in accumulated costs. Additionally, the estimated costs should reflect any expected price increases. These expected price increases should not be blanket provisions for all contract costs, but rather, specific provisions for each type of cost. Expected increases in each of the cost elements such as wages, materials, and overhead items should be taken into consideration separately.

Finally, estimates of costs to complete should be reviewed periodically to reflect new information. Estimates of costs should be examined for price fluctuations and should also be reviewed for possible future problems, such as labor strikes or direct material delays.

Accounting for contract costs is similar to accounting for inventory. Costs necessary to ready the asset for sale would be recorded in the construction-in-progress account, as incurred. CIP would include both direct and indirect costs but would usually not include general and administrative expenses or selling expenses since they are not normally identifiable with a particular contract and should therefore be expensed.

Subcontractor costs.

Since a contractor may not be able to do all facets of a construction project, a subcontractor may be engaged. The amount billed to the contractor for work done by the subcontractor should be included in contract costs. The amount billed is directly traceable to the project and would be included in the CIP account, similar to direct materials and direct labor.

Back charges.

Contract costs may have to be adjusted for back charges. Back charges are billings for costs incurred that the contract stipulated should have been performed by another party. These charges are often disputed by the parties involved.

Example of a back charge situation

The contract states that the subcontractor was to raze the building and have the land ready for construction; however, the contractor/seller had to clear away debris in order to begin construction. The contractor wants to be reimbursed for the work; therefore, the contractor back charges the subcontractor for the cost of the debris removal.

The contractor should treat the back charge as a receivable from the subcontractor and should reduce contract costs by the amount recoverable. If the subcontractor disputes the back charge, the cost becomes a claim. Claims are an amount in excess of the agreed contract price or amounts not included in the original contract price that the contractor seeks to collect. Claims should be recorded as additional contract revenue only if the requirements set forth in IAS 11 are met.

The subcontractor should record the back charge as a payable and as additional contract costs if it is probable that the amount will be paid. If the amount or validity of the liability is disputed, the subcontractor would have to consider the probable outcome in order to determine the proper accounting treatment.

Fixed-Price and Cost-Plus Contracts

IAS 11 recognizes two types of construction contracts that are distinguished based on their pricing arrangements: (1) fixed-price contracts and (2) cost-plus contracts.

Fixed-price contracts are contracts for which the price is not usually subject to adjustment because of costs incurred by the contractor. The contractor agrees to a fixed contract price or a fixed rate per unit of output. These amounts are sometimes subject to escalation clauses.

There are two types of cost-plus contracts.

-

Cost-without-fee contract— Contractor is reimbursed for allowable or otherwise defined costs with no provision for a fee. However, a percentage is added that is based on the foregoing costs.

-

Cost-plus-fixed-fee contract— Contractor is reimbursed for costs plus a provision for a fee. The contract price on a cost-type contract is determined by the sum of the reimbursable expenditures and a fee. The fee is the profit margin (revenue less direct expenses) to be earned on the contract. All reimbursable expenditures should be included in the accumulated contract costs account.

There are a number of possible variations of contracts that are based on a cost-plus-fee arrangement. These could include cost-plus-fixed-fee, under which the fee is a fixed monetary amount; cost-plus-award, under which an incentive payment is provided to the contractor, typically based on the project's timely or on-budget completion; and cost-plus-a-percentage-fee, under which a variable bonus payment will be added to the contractor's ultimate payment based on stated criteria.

Some contracts may have features of both a fixed-price contract and a cost-plus contract. A cost-plus contract with an agreed maximum price is an example of such a contract.

Recognition of Contract Revenue and Expenses

Percentage-of-completion accounting cannot be employed if the quality of information will not support a reasonable level of accuracy in the financial reporting process. Generally, only when the outcome of a construction contract can be estimated reliably, should the contract revenue and contract costs be recognized by reference to the stage of completion at the balance sheet date.

Different criteria have been prescribed by the standard for assessing whether the outcome can be estimated reliably for a contract, depending on whether it is a fixed-price contract or a cost-plus contract. The following are the criteria in each case:

-

If it is a fixed-price contract

Note All conditions should be satisfied.

-

It meets the recognition criteria set by the IASC's Framework; that is

-

Total contract revenue can be measured reliably.

-

It is probable that economic benefits flow to the enterprise.

-

-

Both the contract cost to complete and the stage of completion can be measured reliably.

-

Contract costs attributable to the contract can be identified properly and measured reliably so that comparison of actual contract costs with estimates can be done.

-

-

If it is a cost-plus contract

Note All conditions should be satisfied.

-

It is probable that the economic benefits will flow to the enterprise.

-

The contract costs attributable to the contract, whether or not reimbursable, can be identified and measured reliably.

-

When Outcome of a Contract Cannot Be Estimated Reliably

As stated above, unless the outcome of a contract can be estimated reliably, contract revenue and costs should not be recognized by reference to the stage of completion. IAS 11 establishes the following rules for revenue recognition in cases where the outcome of a contract cannot be estimated reliably:

-

Revenue should be recognized only to the extent of the contract costs incurred that are probable of being recoverable.

-

Contract costs should be recognized as an expense in the period in which they are incurred.

Any expected losses should, however, be recognized immediately.

It is not unusual that during the early stages of a contract, outcome cannot be estimated reliably. This would be particularly likely to be true if the contract represents a type of project with which the contractor has had limited experience in the past.

Contract Costs Not Recoverable Due to Uncertainties

Recoverability of contract costs may be considered doubtful in the case of contracts that have any of the following characteristics:

-

The contract is not fully enforceable.

-

Completion of the contract is dependent on the outcome of pending litigation or legislation.

-

The contract relates to properties that are likely to be expropriated or condemned.

-

The contract is with a customer who is unable to perform its obligations, perhaps because of financial difficulties.

-

The contractor is unable to complete the contract or otherwise meet its obligation under the terms of the contract, as when, for example, the contractor has been experiencing recurring losses and is unable to get financial support from creditors and bankers and may be ready to declare bankruptcy.

In all such cases, contract costs should be expensed immediately. Although the implication is unambiguous, the determination that one or more of the foregoing conditions holds will be subject to some imprecision. Thus, each such situation needs to be assessed carefully on a case-by-case basis.

If and when these uncertainties are resolved, revenue and expenses should again be recognized on the same basis as other construction-type contracts (i.e., by the percentage-of-completion method). However, it is not permitted to restore costs already expensed in prior periods, since the accounting was not in error, given the facts that existed at the time the earlier financial statements were prepared.

Revenue Measurement—Determining the Stage of Completion

The standard recognizes that the stage of completion of a contract may be determined in many ways and that an enterprise uses the method that measures reliably the work performed. The standard further stipulates that depending on the nature of the contract, one of the following methods may be chosen:

-

The proportion that contract costs incurred bear to estimated total contract cost (also referred to as the cost-to-cost method)

-

Survey of work performed method

-

Completion of a physical proportion of contract work (also called units-of-work-performed) method.

Note Progress payments and advances received from customers often do not reflect the work performed.

Each of these methods of measuring progress on a contract can be identified as being either an input or an output measure. The input measures attempt to identify progress in a contract in terms of the efforts devoted to it. The cost-to-cost method is an example of an input measure. Under the cost-to-cost method, the percentage of completion would be estimated by comparing total costs incurred to date to total costs expected for the entire job. Output measures are made in terms of results by attempting to identify progress toward completion by physical measures. The units-of-work-performed method is an example of an output measure. Under this method, an estimate of completion is made in terms of achievements to date. Output measures are usually not considered to be as reliable as input measures.

When the stage of completion is determined by reference to the contract costs incurred to date, the standard specifically refers to certain costs that are to be excluded from contract costs. Examples of such costs are

-

Contract costs that relate to future activity (e.g., construction materials supplied to the site but not yet consumed during construction)

-

Payments made in advance to subcontractors prior to performance of the work by the subcontractor

Example of the percentage-of-completion method

The percentage-of-completion method works under the principle that "recognized income (should) be that percentage of estimated total income...that incurred costs to date bear to estimated total costs." The cost-to-cost method has become one of the most popular measures used to determine the extent of progress toward completion.

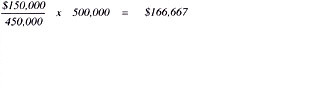

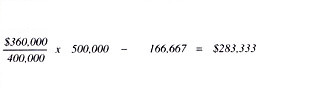

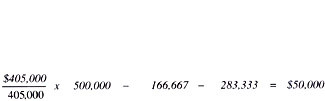

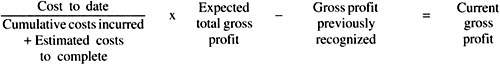

Under the cost-to-cost method, the percentage of revenue to recognize can be determined by the following formula:

By slightly modifying this formula, current gross profit can also be determined.

Example of the percentage-of-completion (cost-to-cost) and completed-contract methods with profitable contract

Assume a $500,000 contract that requires 3 years to complete and incurs a total cost of $405,000. The following data pertain to the construction period:

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| $150,000 | $360,000 | $405,000 |

| 300,000 | 40,000 | -- |

| 100,000 | 370,000 | 30,000 |

| 75,000 | 300,000 | 125,000 |

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construction in progress | 150,000 | 210,000 | 45,000 | |||

| 150,000 | 210,000 | 45,000 | |||

| Contract receivables | 100,000 | 370,000 | 30,000 | |||

| 100,000 | 370,000 | 30,000 | |||

| Cash | 75,000 | 300,000 | 125,000 | |||

| 75,000 | 300,000 | 125,000 | |||

| Billings on contracts | 500,000 | |||||

| Cost of revenues earned | 405,000 | |||||

| 500,000 | |||||

| 405,000 |

Percentage-of-Completion Method Only

| Construction in progress | 16,667 | 73,333 | 5,000 | |||

| Cost of revenues earned | 150,000 | 210,000 | 45,000 | |||

| 166,667 | 283,333 | 50,000 | |||

| Billings on contracts | 500,000 | |||||

| 500,000 | |||||

|

[a]

[b]

[c]

[d]Since the contract was completed and title was transferred in year 3, there are no balance sheet amounts. However, if the project is complete but transfer of title has not taken place, there would be a balance sheet presentation at the end of the third year because the entry closing out the Construction-in-progress account and the Billings account would not have been made yet.

[e]$150,000 (Costs) + 16,667 (Gross profit)

[f]$100,000 (Year 1 Billings) + 370,000 (Year 2 Billings)

[g]$360,000 (Costs) + 16,667 (Gross profit) + 73,333 (Gross profit)

[h]Since the contract was completed and title was transferred in year 3, there are no balance sheet amounts. However, if the project is complete but transfer of title has not taken place, there would be a balance sheet presentation at the end of the third year because the entry closing out the Construction-in-progress account and the Billings account would not have been made yet. | ||||||

| Income Statement Presentation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Total | |

| Percentage-of-completion | ||||

| Contract revenues earned | $166,667 [a] | $283,333 [b] | $ 50,000 [c] | $500,000 |

| Cost of revenues earned | (150,000) | (210,000) | (45,000) | (405,000) |

| Gross profit | $16,667 | $ 73,333 | $ 5,000 | $ 95,000 |

| Completed-contract | ||||

| Contract revenues earned | -- | -- | $500,000 | $500,000 |

| Cost of contracts completed | -- | -- | (405,000) | (405,000) |

| Gross profit | -- | -- | $ 95,000 | $ 95,000 |

|

[a]

[b]

[c]

[d]Since the contract was completed and title was transferred in year 3, there are no balance sheet amounts. However, if the project is complete but transfer of title has not taken place, there would be a balance sheet presentation at the end of the third year because the entry closing out the Construction-in-progress account and the Billings account would not have been made yet.

[e]$150,000 (Costs) + 16,667 (Gross profit)

[f]$100,000 (Year 1 Billings) + 370,000 (Year 2 Billings)

[g]$360,000 (Costs) + 16,667 (Gross profit) + 73,333 (Gross profit)

[h]Since the contract was completed and title was transferred in year 3, there are no balance sheet amounts. However, if the project is complete but transfer of title has not taken place, there would be a balance sheet presentation at the end of the third year because the entry closing out the Construction-in-progress account and the Billings account would not have been made yet. | ||||

| Balance Sheet Presentation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | ||

| Percentage-of-completion | ||||

| Current assets: | ||||

| $25,000 | $ 95,000 | [d] | |

| ||||

| 166,667[e] | |||

| (100,000) | $66,667 | ||

| Current liabilities: | ||||

| $ 20,000 | |||

| Completed-contract | ||||

| Current assets: | ||||

| $25,000 | $ 95,000 | [h] | |

| ||||

| 150,000 | |||

| (100,000) | $50,000 | ||

| Current liabilities: | ||||

| Billings in excess of costs on uncompleted contracts, year 2 ($470,000 - $360,000) | $110,000 | |||

|

[a]

[b]

[c]

[d]Since the contract was completed and title was transferred in year 3, there are no balance sheet amounts. However, if the project is complete but transfer of title has not taken place, there would be a balance sheet presentation at the end of the third year because the entry closing out the Construction-in-progress account and the Billings account would not have been made yet.

[e]$150,000 (Costs) + 16,667 (Gross profit)

[f]$100,000 (Year 1 Billings) + 370,000 (Year 2 Billings)

[g]$360,000 (Costs) + 16,667 (Gross profit) + 73,333 (Gross profit)

[h]Since the contract was completed and title was transferred in year 3, there are no balance sheet amounts. However, if the project is complete but transfer of title has not taken place, there would be a balance sheet presentation at the end of the third year because the entry closing out the Construction-in-progress account and the Billings account would not have been made yet. | ||||

Recognition of Expected Contract Losses

When the current estimate of total contract cost exceeds the current estimate of total contract revenue, a provision for the entire loss on the entire contract should be made. Provisions for losses should be made in the period in which they become evident under either the percentage-of-completion method or the completed-contract method. In other words, when it is probable that total contract costs will exceed total contract revenue, the expected loss should be recognized as an expense immediately. The loss provision should be computed on the basis of the total estimated costs to complete the contract, which would include the contract costs incurred to date plus estimated costs (use the same elements as contract costs incurred) to complete. The provision should be shown separately as a current liability on the balance sheet.

In any year when a percentage-of-completion contract has an expected loss, the amount of the loss reported in that year can be computed as follows:

Reported loss = Total expected loss + All profit previously recognized

Example of the percentage-of-completion and completed-contract methods with loss contract

Using the previous information, if the costs yet to be incurred at the end of year 2 were $148,000, the total expected loss is $8,000 [$500,000 - (360,000 + 148,000)], and the total loss reported in year 2 would be $24,667 ($8,000 + 16,667). Under the completed-contract method, the loss recognized is simply the total expected loss, $8,000.

| Journal entry at end of year 2 | Percentage-of-Completion | Completed contract | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loss on uncompleted long-term contract | 24,667 | 8,000 | ||

| 24,667 | 8,000 | ||

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contract price | $500,000 | $500,000 | $500,000 |

| Estimated total costs: | |||

| $150,000 | $360,000 | $506,000 [a] |

| 300,000 | 148,000 | -- |

| $450.000 | $508,000 | $506,000 |

| $ 16,667 | $ (8,000) | $ (6,000) |

| -- | 16,667 | (8,000) |

| $ 16,667 | $ (24,667) | $ 2,000 |

|

[a]Assumed | |||

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contract price | $500,000 | $500,000 | $500,000 |

| Estimated total costs: | |||

| $150,000 | $360,000 | $506,000 [a] |

| 300,000 | 148,000 | -- |

| $ 50,000 | $ (8,000) | $ (6,000) |

| -- | -- | (8,000) |

| $ -- | $ (8,000) | $ 2,000 |

|

[a]Assumed | |||

Upon completion of the project during year 3, it can be seen that the actual loss was only $6,000 ($500,000 - 506,000); therefore, the estimated loss provision was overstated by $2,000. However, since this is a change of an estimate, the $2,000 difference must be handled prospectively; consequently, $2,000 of income should be recognized in year 3 ($8,000 previously recognized - $6,000 actual loss).

Combining and Segmenting Contracts

The profit center for accounting purposes is usually a single contract, but under some circumstances the profit center may be a combination of two or more contracts, a segment of a contract, or a group of combined contracts. Conformity with explicit criteria set forth in IAS 1 I is necessary to combine separate contracts, or segment a single contract; otherwise, each individual contract is presumed to be the profit center.

For accounting purposes, a group of contracts may be combined if they are so closely related that they are, in substance, parts of a single project with an overall profit margin. A group of contracts, whether with a single customer or with several customers, should be combined and treated as a single contract if the group of contracts

-

Are negotiated as a single package

-

Require such closely interrelated construction activities that they are, in effect, part of a single project with an overall profit margin

-

Are performed concurrently or in a continuous sequence

Segmenting a contract is a process of breaking up a larger unit into smaller units for accounting purposes. If the project is segmented, revenues can be assigned to the different elements or phases to achieve different rates of profitability based on the relative value of each element or phase to the estimated total contract revenue. According to IAS 11, a contract may cover a number of assets. The construction of each asset should be treated as a separate construction contract when

-

The contractor has submitted separate proposals on the separate components of the project

-

Each asset has been subject to separate negotiation and the contractor and customer had the right to accept or reject part of the proposal relating to a single asset

-

The cost and revenues of each asset can be separately identified

Contractual Stipulation for Additional Asset—Separate Contract

The contractual stipulation for an additional asset is a special provision in the international accounting standard. IAS 11 provides that a contract may stipulate the construction of an additional asset at the option of the customer, or the contract may be amended to include the construction of an additional asset. The construction of the additional asset should be treated as a separate construction contract if

-

The additional asset significantly differs (in design, technology or function) from the asset or assets covered by the original contract

-

The price for the additional asset is negotiated without regard to the original contract price

Changes in Estimate

Since the percentage-of-completion method uses current estimates of contract revenue and expenses, it is normal to encounter changes in estimates of contract revenue and costs frequently. Such changes in estimate of the contract's outcome are treated on a par with changes in accounting estimate as defined by IAS 8.

Disclosure Requirements under IAS 11

A number of disclosures are prescribed by IAS 11; some of them are for all the contracts and others are only for contracts in progress at the balance sheet date. These are summarized below.

-

Disclosures relating to all contracts

-

Aggregate amount of contract revenue recognized in the period

-

Methods used in determination of contract revenue recognized in the period

-

-

Disclosures relating to contracts in progress

-

Methods used in determination of stage of completion (of contracts in progress)

-

Aggregate amount of costs incurred and recognized profits (net of recognized losses) to date

-

Amounts of advances received (at balance sheet date)

-

Amount of retentions (at balance sheet date)

-

Financial Statement Presentation Requirements under IAS 11

Gross amounts due from customers should be reported as an asset. This amount is the net of

-

Costs incurred plus recognized profits, less

-

The aggregate of recognized losses and progress billings.

This represents, in the case of contracts in progress, excess of contract costs incurred plus recognized profits, net of recognized losses, over progress billings.

Gross amounts due to customers should be reported as a liability. This amount is the net of

-

Costs incurred plus recognized profits, less

-

The aggregate of the recognized losses and progress billings.

This represents, in the case of contract work in progress, excess of progress billings over contract costs incurred plus recognized profits, net of recognized losses.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 147