Concepts, Rules, and Examples

Benefits of Cash Flow Statements

The concepts underlying the balance sheet and the income statement have long been established in financial reporting; they are, respectively, the stock measure or a snapshot at a point in time of an entity's resources and obligations, and a summary of the entity's economic performance over a period of time. The third major financial statement, the cash flow statement, is a more recent innovation but has evolved substantially since introduced. What has ultimately developed into the cash flow statement began life as a flow statement that reconciled changes in enterprise resources over a period of time but in a fundamentally different manner than did the income statement.

Most of the basic progress on this financial statement occurred in the United States, where during the 1950s and early 1960s a variety of formats and concepts were experimented with. By the mid-1960s the most common approach in the United States was that of reporting the sources and applications (or uses) of funds, although such reporting did not become mandatory until 1971, and even then, funds could be defined by the reporting entity in at least four different ways, including as cash and as net working capital (current assets minus current liabilities).

One reason why the financial statement preparer community did not more quickly embrace a cash flow concept is that the accounting profession had long had a significant aversion to the cash basis measurement of enterprise operating performance. This was largely the result of its commitment to accrual basis accounting, which recognizes revenues when earned and expenses when incurred, and which views cash flow reporting as a back door approach to cash basis accounting. By focusing instead on funds, which most typically was defined as net working capital, items such as receivables and payables were included, thereby preserving the essential accrual basis characteristic of the flow measurement. On the other hand, this failed to give statement users meaningful insight into the entities' sources and uses of cash, which is germane to an evaluation of the reporting entity's liquidity and solvency.

By the 1970s there was widespread recognition of the myriad problems associated with funds flow reporting, including the required use of the all financial resources approach, under which all major noncash (and nonfund) transactions, such as exchanges of stock or debt for plant assets, were included in the funds flow statement. This ultimately led to a renewed call for cash flow reporting. Most significantly, the FASB's conceptual framework project of the late 1970s to mid-1980s identified usefulness in predicting future cash flows as a central purpose of the financial reporting process. This presaged the nearly universal move away from funds flows to cash flows as a third standard measurement to be incorporated in financial reports.

Cash flow statements thus became required in the late 1980s in the United States, with the United Kingdom following along soon thereafter with an approach that largely mirrored the US standard; albeit with a somewhat refined classification scheme that solves some of the problems inherent in the US model (as described in greater detail below) and which, in the 1996 revision of FRS 1, has embraced an even more extensive classification scheme, as described below. The international accounting standard, which was adopted a year after that of the United Kingdom (both of these were revisions to earlier requirements that had mandated the use of funds flow statements), embraces the somewhat simpler US approach but offers greater flexibility, thus effectively incorporating the UK view without adding to the structural complexity of the cash flow statement itself.

Today, the clear consensus of national and international accounting standard setters is that the statement of cash flows is a necessary component of complete financial reporting. The perceived benefits of presenting the statement of cash flows in conjunction with the statement of financial position (balance sheet) and the statement of income (or operations) have been highlighted by IAS 7 to be as follows:

-

It provides an insight into the financial structure of the enterprise (including its liquidity and solvency) and its ability to affect the amounts and timing of cash flows in order to adapt to changing circumstances and opportunities.

The statement of cash flows discloses important information about the cash flows from operating, investing, and financing activities, information that is not available or as clearly discernible in either the balance sheet or the income statement. The additional disclosures which are either recommended by IAS 7 (such as those relating to undrawn borrowing facilities or cash flows that represent increases in operating capacity) or required to be disclosed by the standard (such as that about cash held by the enterprise but not available for use) provide a wealth of information for the informed user of financial statements. Taken together, the statement of cash flows coupled with these required or recommended disclosures provide the user with vastly more insight into the entity's performance and position, and its probable future results, than would the balance sheet and income statement alone.

-

It provides additional information to the users of financial statements for evaluating changes in assets, liabilities, and equity of an enterprise.

When comparative balance sheets are presented, users are given information about the enterprise's assets and liabilities at the end of each of the years. Were the statement of cash flows not presented as an integral part of the financial statements, it would be necessary for users of comparative financial statements either to wonder how and why certain amounts reported on the balance sheet changed from one period to another, or to compute (at least for the latest year presented) approximations of these items for themselves. At best, however, such a do-it-yourself approach would derive the net changes (the increase or decrease) in the individual assets and liabilities and attribute these to normally related income statement accounts. (For example, the net change in accounts receivable from the beginning to the end of the year would be used to convert reported sales to cash-basis sales or cash collected from customers.) More complex combinations of events (such as the acquisition of another entity, along with its accounts receivables, which would be an increase in that asset which was not related to sales to customers by the reporting entity during the period) would not immediately be comprehensible and might lead to incorrect interpretations of the data unless an actual cash flow statement were presented.

-

It enhances the comparability of reporting of operating performance by different enterprises because it eliminates the effects of using different accounting treatments for the same transactions and events.

There was considerable debate even as early as the 1960s and 1970s over accounting standardization, which led to the emergence of cash flow accounting. The principal argument in support of cash flow accounting by its earliest proponents was that it avoids the arbitrary allocations inherent in accrual accounting. For example, cash flows provided by or used in operating activities are derived, under the indirect method, by adjusting net income (or loss) for items such as depreciation and amortization, which might have been computed by different entities using different accounting methods. Thus, accounting standardization will be achieved by converting the accrual-basis net income to cash-basis income, and the resultant figures will become comparable across enterprises.

-

It serves as an indicator of the amount, timing, and certainty of future cash flows. Furthermore, if an enterprise has a system in place to project its future cash flows, the statement of cash flows could be used as a touchstone to evaluate the accuracy of past projections of those future cash flows. This benefit is elucidated by the standard as follows:

-

The statement of cash flows is useful in comparing past assessments of future cash flows against current year's cash flow information, and

-

It is of value in appraising the relationship between profitability and net cash flows, and in assessing the impact of changing prices.

-

Exclusion of Noncash Transactions

The statement of cash flows includes only inflows and outflows of cash and cash equivalents. Accordingly, it excludes all transactions that do not directly affect cash receipts and payments. However, IAS 7 does require that the effects of transactions not resulting in receipts or payments of cash be disclosed elsewhere in the financial statements. The reason for not including noncash transactions in the statement of cash flows and placing them elsewhere in the financial statements (e.g., the footnotes) is that it preserves the statement's primary focus on cash flows from operating, investing, and financing activities.

Components of Cash and Cash Equivalents

The statement of cash flows, under the various national and international standards, may or may not include transactions in cash equivalents as well as cash. Under US standards, for example, preparers may choose to define cash as "cash and cash equivalents," as long as the same definition is used in the balance sheet as in the cash flow statement (i.e., the cash flow statement must tie to a single caption on the balance sheet). With the recent dramatic revision to the UK standard on cash flow reporting, on the other hand, the revised UK FRS 1 now defines cash flows to include movements only in "cash." IAS 7, on the other hand, rather clearly required that the changes in both cash and cash equivalents be explained by the cash flow statement. Thus, the three major standards (US, UK, and International) have taken three different roads (optionally including cash equivalents; mandatorily excluding cash equivalents; and including cash equivalents, respectively) to the presentation of the statement of cash flows.

Cash and cash equivalents include unrestricted cash (meaning cash actually on hand, or bank balances whose immediate use is determined by the management), other demand deposits, and short-term investments whose maturities at the date of acquisition by the enterprise were three months or less. Equity investments do not qualify as cash equivalents unless they fit the definition above of short-term maturities of three months or less. Redeemable preference shares, if acquired within three months of their predetermined redemption date, would meet the criteria above since they are, in substance, cash equivalents. These are very infrequently encountered circumstances, however.

Bank borrowings are normally considered as financing activities. However, in some countries, bank overdrafts play an integral part in the enterprise's cash management, and as such, overdrafts are to be included as a component of cash equivalents if the following conditions are met:

-

The bank overdraft is repayable on demand, and

-

The bank balance often fluctuates from positive to negative (overdraft).

Postdated checks (cheques), commonly referred to as PDC, are used a great deal in business transactions in certain countries. In such situations, vendors usually insist upon PDC to back up the credit extended by them in the normal course of business. Banks will then offer to discount these postdated checks (on a recourse basis, normally) if the discounting party's credit is strong, and thus vendors may end up collecting their receivables before the due date. Under such circumstances, where vendors use PDC as an integral component of their cash management strategy, it could very well be argued that PDC should be considered cash equivalents. However, if it is not certain at the balance sheet date whether or not the PDC are to be discounted, a case could be made to at least consider those PDC that mature within three months after the balance sheet date as cash equivalents (while those having original maturities longer than three months would be precluded from being so treated). The customer who issued those PDC, however, has no control over them once they are issued and would not be able to use them as an integral part of its cash management; thus, in the debtors' financial statements PDC are simply accounts payable and are not cash transactions until the dates of the PDC occur.

Statutory deposits by banks (i.e., those held with the central bank for regulatory compliance purposes) are often included in the same balance sheet caption as cash. There is a difference of opinion and even some controversy in certain countries, which is fairly evident from scrutiny of published financial statements of banks, as to whether these deposits should be considered a cash equivalent or an operating asset. If the latter, changes in amount would be presented in the operating activities section of the cash flow statement, and the item could not then be combined with cash in the balance sheet. Since the appendix to IAS 7, which illustrates the application of the standard to cash flow statements of financial institutions, does not include statutory deposits with the central bank as a cash equivalent, the authors have concluded that there is little logic to support the alternative presentation of this item as a cash equivalent. Given the fact that deposits with central banks are more or less permanent (and in fact would be more likely to increase over time than to be diminished, given a going concern assumption about the reporting financial institution) the presumption must be that these are not cash equivalents in normal practice.

Classifications in the Statement of Cash Flows

The statement of cash flows prepared in accordance with international accounting standards (and also in accordance with US GAAP) requires classification into these three categories:

-

Investing activities include the acquisition and disposition of property, plant and equipment and other long-term assets and debt and equity instruments of other enterprises that are not considered cash equivalents or held for dealing or trading purposes. Investing activities include cash advances and collections on loans made to other parties (other than advances and loans of a financial institution).

-

Financing activities include obtaining resources from and returning resources to the owners. Also included is obtaining resources through borrowings (short-term or long-term) and repayments of the amounts borrowed.

-

Operating activities include all transactions that are not investing and financing activities. In general, cash flows that relate to, or are the corollary of, items reported in the income statement are operating cash flows. Operating activities are principal revenue-producing activities of an enterprise and include delivering or producing goods for sale and providing services.

While both US and international accounting standards define these three components of cash flows, the international standards offer somewhat more flexibility in how certain types of cash flows are categorized. For example, under US GAAP, interest paid must be included in operating activities, but under the provisions of IAS 7 this may be consistently included in either operating or financing activities. (These and other discrepancies among the standards will be discussed further throughout this chapter.) This is a reflection of the fact that although interest expense is operating in the sense of being an item that is reported in the income statement, it also clearly relates to the entity's financing activities.

The original UK standard on cash flow reporting, FRS 1, tried to solve this dilemma by defining five, not merely three, categories for the cash flow statement. In addition to the three standard classifications discussed above, it added two others: "returns on investments and servicing of finance," and "taxation." The first of these added categories was used to report all dividends and interest paid or received, leaving the traditional financing section to report only principal transactions, and averting the issue of whether dividends and interest are operating, investing, or financing in nature. The segregation of taxation into a category of its own avoids a very similar debate, since taxation can be the result of normal operating activities as well as of investing or financing events.

The recently revised UK standard on cash flow reporting, which is also denoted as FRS 1, now requires classification into the following eight categories:

-

Operating activities

-

Returns on investments and servicing of finance

-

Taxation

-

Capital expenditure and financial investment

-

Acquisitions and disposals

-

Equity dividends paid

-

Management of liquid resources

-

Financing

As a result of this new classification scheme, financial statements prepared in conformity with UK GAAP will differ rather notably from those prepared under either US GAAP or IAS. With the growing worldwide interest in the standardization of financial reporting in general, and in the international accounting standards in particular, it remains to be seen how well this unorthodox approach will be accepted. In any event, it is deemed to be extremely unlikely that the IAS will be modified to acknowledge the UK approach.

The following are examples of the statement of cash flows classification under the provisions of IAS 7:

| Operating | Investing | Financing | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cash inflows |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| Cash outflows |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

[a]Unless held for trading purposes or considered to he cash equivalents. | |||

Noncash investing and financing activities should, according to IAS 7, be disclosed in the footnotes to financial statements ("elsewhere" is how the standard actually identifies this), but apparently are not intended to be included in the cash flow statement itself. This contrasts somewhat with the US standard, SFAS 95, which encourages inclusion of this supplemental information on the face of the statement of cash flows, although this may, under that standard, be relegated to a footnote as well. (The UK standard on cash flow reporting, FRS 1, also requires that major noncash transactions be disclosed in a note to the cash flow statement.) Examples of significant noncash financing and investing activities might include

-

Acquiring an asset through a finance lease

-

Conversion of debt to equity

-

Exchange of noncash assets or liabilities for other noncash assets or liabilities

-

Issuance of stock to acquire assets

Basic example of a classified statement of cash flows

| Net cash flows from operating activities | $ xxx | |

| Cash flows from investing activities: | ||

| $(xxx) | |

| xx | |

| xx | |

| (xx) | |

| Cash flows from financing activities: | ||

| xxx | |

| (xx) | |

| (xx) | |

| xx | |

| Effect of exchange rate changes on cash | xx | |

| Net increase in cash and cash equivalents | $ xxx | |

| Cash and cash equivalents at beginning of year | xxx | |

| Cash and cash equivalents at end of year | $xxxx |

Footnote Disclosure of Noncash Investing and Financing Activities

-

Note 4: Supplemental Cash Flow Statement Information

Significant noncash investing and financing transactions:

-

Conversion of bonds into common stock

$ xxx

-

Property acquired under finance leases

xxx

$ xxx

-

Reporting Cash Flows from Operating Activities

Direct vs. indirect method.

The operating activities section of the statement of cash flows can be presented under the direct or the indirect method. However, the IASC has expressed a preference for the direct method of presenting net cash from operating activities. In this regard the IASC was probably following in the well-worn path of the FASB in the United States, which similarly urged that the direct method of reporting be adhered to. Under UK GAAP, however, though the UK Accounting Standards Board considered the advantages of the direct method in developing FRS 1, it was noted that it did not believe that in all cases the benefits to users outweighed the costs to the reporting entity of providing that mode of reporting. The UK Board remains convinced of this view, and the revised FRS 1 continues to encourage the direct method only where the potential benefits to users outweigh the costs of providing it. For their part, preparers of financial statements in the other parts of the world, like those in the US, have chosen overwhelmingly to ignore the recommendation of the IASC, preferring by a very large margin to use the indirect method in lieu of the recommended direct method.

The direct method shows the items that affected cash flow and the magnitude of those cash flows. Cash received from, and cash paid to, specific sources (such as customers and suppliers) are presented, as opposed to the indirect method's converting accrual-basis net income (loss) to cash flow information by means of a series of add-backs and deductions. Entities using the direct method are required by IAS 7 to report the following major classes of gross cash receipts and gross cash payments:

-

Cash collected from customers

-

Interest and dividends received[1]

-

Cash paid to employees and other suppliers

-

Interest paid[2]

-

Income taxes paid

-

Other operating cash receipts and payments

Given the availability of alternative modes of presentation of interest and dividends received, and of interest paid, it is particularly critical that the policy adopted be followed consistently. Since the face of the statement of cash flows will in almost all cases make it clear what approach has been elected, it is not usually necessary to spell this out in the accounting policy note to the financial statements, although this certainly can be done if it would be useful to do so.

An important advantage of the direct method is that it permits the user to better comprehend the relationships between the company's net income (loss) and its cash flows. For example, payments of expenses are shown as cash disbursements and are deducted from cash receipts. In this way the user is able to recognize the cash receipts and cash payments for the period. Formulas for conversion of various income statement amounts for the direct method presentation from the accrual basis to the cash basis are summarized below.

| Accrual basis | Additions | Deductions | Cash basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Net sales | + Beginning AR | - Ending AR AR written off | = Cash received from customers |

| Cost of goods sold | + Ending inventory Beginning AP | - Depreciation and amortization[a] Beginning inventory Ending AP | = Cash paid to suppliers |

| Operating expenses | + Ending prepaid expenses Beginning accrued expenses | - Depreciation and amortization Beginning prepaid expenses Ending accrued expenses payable Bad debts expense | = Cash paid for operating expenses |

|

[a]Applies to a manufacturing entity only | |||

From the foregoing it can be appreciated that the amounts to be included in the operating section of the statement of cash flows, when the direct approach is utilized, are derived amounts that must be computed (although the computations are not onerous); they are not, generally, amounts that exist as account balances simply to be looked up and then placed in the statement. The extra effort needed to prepare the direct method operating cash flow data may be a contributing cause of why this method has been distinctly unpopular with preparers. (There is an extra reason why the direct method is unpopular with entities that report in conformity with US GAAP: SFAS 95 requires that when the direct method is used, a supplementary schedule be prepared reconciling net income to net cash flows from operating activities, which effectively means that both the direct and indirect methods must be employed. This rule does not apply under international accounting standards, however.)

The indirect method (sometimes referred to as the reconciliation method) is the most widely used means of presentation of cash from operating activities, primarily because it is easier to prepare. It focuses on the differences between net operating results and cash flows. The indirect format begins with net income (or loss), which can be obtained directly from the income statement. Revenue and expense items not affecting cash are added or deducted to arrive at net cash provided by operating activities. For example, depreciation and amortization would be added back because these expenses reduce net income without affecting cash.

The statement of cash flows prepared using the indirect method emphasizes changes in the components of most current asset and current liability accounts. Changes in inventory, accounts receivable, and other current accounts are used to determine the cash flow from operating activities. Although most of these adjustments are obvious (most preparers simply relate each current asset or current liability on the balance sheet to a single caption in the income statement), some changes require more careful analysis. For example, it is important to compute cash collected from sales by relating sales revenue to both the change in accounts receivable and the change in the related bad debt allowance account.

As another example of possible complexity in computing the cash from operating activities, the change in short-term borrowings resulting from the purchase of equipment would not be included, since it is not related to operating activities. Instead, these shortterm borrowings would be classified as a financing activity. Other adjustments under the indirect method include changes in the account balances of deferred income taxes, minority interest, unrealized foreign currency gains or losses, and the income (loss) from investments under the equity method.

IAS 7 offers yet another alternative way of presenting the cash flows from operating activities. This could be referred to as the modified indirect method. Under this variant of the indirect method, the starting point is not net income but rather revenues and expenses as reported in the income statement. In essence, this approach is virtually the same as the regular indirect method, with two more details: revenues and expenses for the period. There is no equivalent rule under US GAAP.

The following summary, actually simply an expanded balance sheet equation, may facilitate understanding of the adjustments to net income necessary for converting accrual-basis net income to cash-basis net income when using the indirect method.

| Current assets[a] | - | Fixed assets | = | Current liabilities | + | Long-term liabilities | + | Income | Accrual income adjustment to convert to cash flow | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Increase | = | Increase | Decrease | ||||||

| 2. | Decrease | = | Decrease | Increase | ||||||

| 3. | = | Increase | Decrease | Increase | ||||||

| 4. | = | Decrease | Increase | Decrease | ||||||

|

[a]Other than cash and cash equivalents | ||||||||||

For example, using row 1 in the above chart, a credit sale would increase accounts receivable and accrual-basis income but would not affect cash. Therefore, its effect must be removed from the accrual income to convert to cash income. The last column indicates that the increase in a current asset balance must be deducted from income to obtain cash flow.

Similarly, an increase in a current liability, row three, must be added to income to obtain cash flows (e.g., accrued wages are on the income statement as an expense, but they do not require cash; the increase in wages payable must be added back to remove this noncash flow expense from accrual-basis income).

Under the US GAAP, when the indirect method is employed, the amount of interest and income taxes paid must be included in the related disclosures (supplemental schedule). However, under international accounting standards, as illustrated by the appendix to IAS 7, instead of disclosing them in the supplemental schedules, they are shown as part of the operating activities under both the direct and indirect methods. (Examples presented later in the chapter illustrate this.)

The major drawback to the indirect method involves the user's difficulty in comprehending the information presented. This method does not show from where the cash was received or to where the cash was paid. Only adjustments to accrual-basis net income are shown. In some cases the adjustments can be confusing. For instance, the sale of equipment resulting in an accrual-basis loss would require that the loss be added to net income to arrive at net cash from operating activities. (The loss was deducted in the computation of net income, but because the sale will be shown as an investing activity, the loss must be added back to net income.)

Although the indirect method is more commonly used in practice, the IASC and the FASB both encourage enterprises to use the direct method. As pointed out by IAS 7, a distinct advantage of the direct method is that it provides information that may be useful in estimating or projecting future cash flows, a benefit that is clearly not achieved when the indirect method is utilized instead. Both the direct and indirect methods are presented below.

| Direct method | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cash flows from operating activities: | ||

| $xxx | |

| xxx | |

| Cash provided by operating activities | $xxx | |

| (xxx) | |

| (xxx) | |

| (xxx) | |

| Cash disbursed for operating activities | ($xxx) | |

| Net cash flows from operating activities | $xxx | |

|

[a]Alternatively, could be classified as investing cash flow.

[b]Taxes paid are usually classified as operating activities. However, when it is practical to identify the tax cash flow with an individual transaction that gives rise to cash flows that are classified as investing or financing activities, then the tax cash flow is classified as an investing or financing activity as appropriate. | ||

| Indirect method | |

|---|---|

| Cash flows from operating activities: | |

| $ xx |

| |

| xx |

| xx |

| xx |

| xx |

| (xx) |

| xx |

| xx |

| xx |

| (xx) |

| (xx) |

| $xxx |

|

[a]The appendix to IAS 7 uses the term "working capital changes," but the authors believe that "changes in operating assets and liabilities" is preferable since the emphasis has clearly shifted from working capital changes, and the related concept of fund flows, to cash flows by the supplanting of the erstwhile IAS 7, which dealt with the now obsolete "statement of changes in financial position." | |

Other Requirements

Gross vs. net basis.

The emphasis in the statement of cash flows is on gross cash receipts and cash payments. For instance, reporting the net change in bonds payable would obscure the financing activities of the entity by not disclosing separately cash inflows from issuing bonds and cash outflows from retiring bonds.

IAS 7 (paragraph 22) specifies two exceptions where netting of cash flows is allowed. Items with quick turnovers, large amounts, and short maturities may be presented as net cash flows. Cash receipts and payments on behalf of customers when the cash flows reflect the activities of the customers rather than those of the enterprise may also be reported on a net rather than a gross basis.

Foreign currency cash flows.

Foreign operations must prepare a separate statement of cash flows and translate the statement to the reporting currency using the exchange rate in effect at the time of the cash flow (a weighted-average exchange rate may be used if the result is substantially the same). This translated statement is then used in the preparation of the consolidated statement of cash flows. Noncash exchange gains and losses recognized on the income statement should be reported as a separate item when reconciling net income and operating activities. For a more detailed discussion about the exchange rate effects on the statement of cash flows, see Chapter 20.

Cash flow per share.

There is presently no requirement either under the international accounting standards or under US GAAP to disclose such information in the financial statements of an enterprise, unlike the requirement to report earnings per share (EPS). In fact, cash flow per share is a somewhat disreputable concept, since it was sometimes touted in an earlier era as being indicative of an entity's "real" performance, when of course it is not a meaningful alternative to earnings per share because, for example, enterprises that are self-liquidating by selling productive assets can generate very positive total cash flows, and hence, cash flows per share, while decimating the potential for future earnings. Since, unlike a comprehensive cash flow statement, cash flow per share cannot reveal the components of cash flow (operating, investing, and financing), its usage could be misleading.

Exemption from Presentation of a Statement of Cash Flows under US GAAP and IAS

Under US GAAP, as set forth in SFAS 102, a statement of cash flows is not required for a defined benefit pension plan that presents financial information consistent with the guidelines of SFAS 35. Other employee benefit plans are exempted provided that the financial information presented is similar to the requirements of SFAS 35. Investment enterprises or a common trust fund held for the collective investment and reinvestment of moneys are not required to provide a statement of cash flows if the following conditions are met:

-

Substantially all of the entity's investments are highly liquid

-

Entity's investments are carried at market value

-

Entity had little or no debt, based on average debt outstanding during the period in relation to average total assets

-

Entity provides a statement of changes in net assets

However, with the issuance of SFAS 117, the requirements for presentation of statements of cash flows have been made almost universal except in the case of investment companies and employee benefit plans, which are still exempted. IAS 7, on the other hand, categorically states that all enterprises regardless of the nature of their activities should present a statement of cash flows as an integral part of their financial reports. No exceptions have been identified to this requirement.

Net Reporting by Financial Institutions

IAS 7 permits financial institutions to report cash flows arising from certain activities on a net basis. These activities, and the related conditions under which net reporting would be acceptable, are as follows:

-

Cash receipts and payments on behalf of customers when the cash flows reflect the activities of the customers rather than those of the bank. For example, the acceptance and repayment of demand deposits

-

Cash flows relating to deposits with fixed maturity dates

-

Placements and withdrawals of deposits from other financial institutions

-

Cash advances and loans to banks customers and repayments thereon

US GAAP has similar requirements. According to SFAS 104, banks, savings institutions, and credit unions are allowed to report net cash receipts and payments for the following:

-

Deposits placed with other financial institutions

-

Withdrawals of deposits

-

Time deposits accepted

-

Repayments of deposits

-

Loans made to customers

-

Principal collections of loans

Reporting Futures, Forward Contracts, Options, and Swaps

IAS 7 stipulates that cash payments for and cash receipts from futures contracts, forward contracts, option contracts, and swap contracts are normally classified as investing activities, except

-

When such contracts are held for dealing or trading purposes and thus represent operating activities

-

When the payments or receipts are considered by the enterprise as financing activities and are reported accordingly

Further, when a contract is accounted for as a hedge of an identifiable position, the cash flows of the contract are classified in the same manner as the cash flows of the position being hedged. In this matter, US GAAP establishes similar requirements (by SFAS 104).

Reporting Extraordinary Items in the Cash Flow Statement

The cash flows associated with extraordinary items should be disclosed separately as arising from operating, investing, or financing activities in the statement of cash flows, as appropriate. By way of contrast, US GAAP permits, but does not require, separate disclosure of cash flows related to extraordinary items. If an entity reporting under US GAAP chooses to make this disclosure, however, it is expected to do so consistently in all periods.

Reconciliation of Cash and Cash Equivalents

An enterprise should disclose the components of cash and cash equivalents and should present a reconciliation of the difference, if any, between the amounts reported in the statement of cash flows and equivalent items reported in the balance sheet. By contrast, under the US GAAP the definition must tie to a specific caption on the balance sheet. For example, if short-term investments are shown as a separate caption in the balance sheet, the definition of cash for the purposes of the statement of cash flows must include "cash" alone (and not also include short-term investments). On the other hand, if "cash and cash equivalents" is the adopted definition in the statement of cash flows, a single caption in the balance sheet must include both "cash" and "short-term investments."

Acquisitions and Disposals of Subsidiaries and Other Business Units

IAS 7 requires that the aggregate cash flows from acquisitions and from disposals of subsidiaries or other business units should be presented separately as part of the investing activities section of the statement of cash flows. The following disclosures have also been prescribed by IAS 7 in respect to both acquisitions and disposals:

-

The total consideration included

-

The portion thereof discharged by cash and cash equivalents

-

The amount of cash and cash equivalents in the subsidiary or business unit acquired or disposed

-

The amount of assets and liabilities (other than cash and cash equivalents) acquired or disposed, summarized by major category

Other Disclosures Required or Recommended by IAS 7

Certain additional information may be relevant to the users of financial statements in gaining an insight into the liquidity or solvency of an enterprise. With this objective in mind, IAS 7 sets forth other disclosures that are required or in some cases, recommended.

-

Required disclosure—Amount of significant cash and cash equivalent balances held by an enterprise that are not available for use by the group should be disclosed along with a commentary by management.

-

Recommended disclosures—The disclosures that are encouraged are the following:

-

Amount of undrawn borrowing facilities, indicating restrictions on their use, if any

-

In case of investments in joint ventures, which are accounted for using proportionate consolidation, the aggregate amount of cash flows from operating, investing and financing activities that are attributable to the investment in the joint venture

-

Aggregate amount of cash flows that are attributable to the increase in operating capacity separately from those cash flows that are required to maintain operating capacity

-

Amount of cash flows segregated by reported industry and geographical segments

-

The disclosures above recommended by the IAS 7, although difficult to present, are unique since such disclosures are not required even under the US GAAP. They are useful in enabling the users of financial statements to understand the enterprise's financial position better.

Basic example of the preparation of the cash flow statement under IAS 7 using a worksheet approach

Using the following financial information for ABC (Middle East) Ltd., preparation and presentation of the cash flow statement according to the requirements of IAS 7 are illustrated. (Note that all figures in this example are in thousands of US dollars.)

| Assets | 2003 | 2002 |

|---|---|---|

| Cash and cash equivalents | $ 3,000 | $ 1,000 |

| Debtors | 5,000 | 2,500 |

| Inventories | 2,000 | 1,500 |

| Preoperative expenses | 1,000 | 1,500 |

| Due from associates | 19,000 | 19,000 |

| Property, plant, and equipment cost | 12,000 | 22,500 |

| (5,000) | (6,000) |

| Property, plant, and equipment, net | 7,000 | 16,500 |

| Total assets | $37,000 | $42,000 |

| Liabilities | ||

| Accounts payable | $ 5,000 | $12,500 |

| Income taxes payable | 2,000 | 1,000 |

| Deferred taxes payable | 3,000 | 2,000 |

| Total liabilities | 10,000 | 15,500 |

| Shareholders' equity | ||

| Share capital | 6,500 | 6,500 |

| Retained earnings | 20,500 | 20,000 |

| Total shareholders' equity | 27,000 | 26,500 |

| Total liabilities and shareholders' equity | $37,000 | $42,000 |

| Sales | $ 30,000 |

| Cost of sales | (10,000) |

| Gross operating income | 20,000 |

| Administrative and selling expenses | (2,000) |

| Interest expenses | (2,000) |

| Depreciation of property, plant and equipment | (2,000) |

| Amortization of preoperative expenses | (500) |

| Investment income | 2,000 |

| Net income before taxation and extraordinary item | 15,500 |

| Extraordinary item—proceeds from settlement with government for expropriation of business | 1,000 |

| Net income after extraordinary item | 16,500 |

| Taxes on income | (4,000) |

| Net income | $12,500 |

The following additional information is relevant to the preparation of the statement of cash flows:

-

Equipment with a net book value of $7,500 and original cost of $10,500 was sold for $7,500.

-

All sales made by the company are credit sales.

-

The company received cash dividends (from investments) amounting to $2,000, recorded as income in the income statement for the year ended December 31, 2003.

-

The company received $1,000 in settlement from government for the expropriation of business, which is accounted for as an extraordinary item.

-

The company declared and paid dividends of $12,000 to its shareholders.

-

Interest expense for the year 2003 was $2,000, which was fully paid during the year. All administration and selling expenses incurred were paid during the year.

-

Income tax expense for the year 2003 was provided at $4,000, out of which the company paid $2,000 during 2003 as an estimate.

A worksheet can be prepared to ease the development of the cash flow statement, as follows:

| 2003 | 2002 | Change | Operating | Investing | Financing | Cash and equivalents | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cash and equivalents | 3,000 | 1,000 | 2,000 | 2,000 | |||

| Debtors | 5,000 | 2,500 | 2,500 | (2,500) | |||

| Inventories | 2,000 | 1,500 | 500 | (500) | |||

| Preoperative expenses | 1,000 | 1,500 | (500) | 500 | |||

| Due from associates | 19,000 | 19,000 | 0 | ||||

| Property, plant, and equipment | 7,000 | 16,500 | (9,500) | 2,000 | 7,500 | ||

| Accounts payable | 5,000 | 12,500 | 7,500 | (7,500) | |||

| Income taxes payable | 2,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | |||

| Deferred taxes payable | 3,000 | 2,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | |||

| Share capital | 6,500 | 6,500 | 0 | ||||

| Retained earnings | 20,500 | 20,000 | 500 | 10,500 | 2,000 | (12,000) | -- |

| 4,500 | 9,500 | (12,000) | 2,000 |

| Cashflows from operating activities | ||

| $ 27,500 | |

| (20,000) | |

| 7,500 | |

| (2,000) | |

| (2,000) | |

| 3,500 | |

| 1,000 | |

| $ 4,500 | |

| Cash flows from investing activities | ||

| 7,500 | |

| 2,000 | |

| 9,500 | |

| Cash flows from financing activities | ||

| (12,000) | |

| (12,000) | |

| 2,000 | |

| 1,000 | |

| $ 3,000 | |

|

[a]Cash flows associated with extraordinary items should be classified as arising from operating, investing, or financing activities as appropriate and disclosed separately. Thus, part of the proceeds (i.e., those pertaining to property, plant and equipment) could be presented as cash flows from investing activities, if information needed to do so is available. | ||

Details of the computations of amounts shown in the statement of cash flows are as follows:

| Cash received from customers during the year | |||

| 30,000 | ||

| Accounts receivable, beginning of year | 2,500 | |

| Accounts receivable, end of year | (5,000) | |

| $27,500 | ||

| Cash paid to suppliers and employees | |||

| 10,000 | ||

| Inventory, beginning of year | (1,500) | |

| Inventory, end of year | 2,000 | |

| Accounts payable, beginning of year | 12,500 | |

| Accounts payable, end of year | (5,000) | |

| Administrative and selling expenses paid | 2,000 | |

| $20,000 | ||

| $ 2,000 | ||

| Income taxes paid during the year | |||

| 4,000 | ||

| Beginning income taxes payable | 1,000 | |

| Beginning deferred taxes payable | 2,000 | |

| Ending income taxes payable | (2,000) | |

| Ending deferred taxes payable | (3,000) | |

| $ 2,000 | ||

| $ 1,000 | ||

| $ 7,500 | ||

| $ 2,000 | ||

| $12,000 | ||

| Cash flows from operating activities | ||

| $ 15,500 | |

| ||

| 2,000 | |

| 500 | |

| (2,000) | |

| 2,000 | |

| 18,000 | |

| (2,500) | |

| (500) | |

| (7,500) | |

| 7,500 | |

| (2,000) | |

| (2,000) | |

| 3,500 | |

| 1,000 | |

| 4,500 | |

| Cash flows from investing activities | ||

| 7,500 | |

| 2,000 | |

| 9,500 | |

| Cash flows from financing activities | ||

| (12,000) | |

| (12,000) | |

| 2,000 | |

| 1,000 | |

| $ 3,000 | |

|

[a]The format of the statement of cash flows presented under the indirect method is in accordance with the presentation in the appendix of IAS 7; thus the wording "working capital changes" has been used instead of "changes in operating assets and liabilities," as recommended by the authors. For a detailed discussion on this subject, refer to the earlier section of this chapter.

[b]Cash flows associated with extraordinary items should be classified as arising from operating, investing, or financing activities as appropriate and disclosed separately. Thus, part of the proceeds (i.e., those pertaining to property, plant and equipment) could be presented as cash flows from investing activities, if information needed to do so is available. | ||

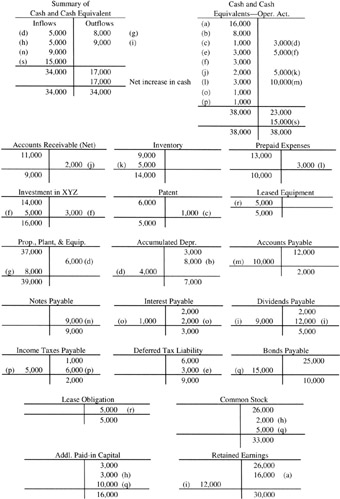

A Comprehensive Example of the Preparation of the Cash Flow Statement Using the T-Account Approach

Under a cash and cash equivalents basis, the changes in the cash account and any cash equivalent account is the bottom line figure of the statement of cash flows. Using the 2002 and 2003 balance sheets shown below, an increase of $17,000 can be computed. This is the difference between the totals for cash and treasury bills between 2002 and 2003 ($33,000 - $16,000).

When preparing the statement of cash flows using the direct method, gross cash inflows from revenues and gross cash outflows to suppliers and for expenses are presented in the operating activities section.

In preparing the reconciliation of net income to net cash flow from operating activities (indirect method), changes in all accounts other than cash and cash equivalents that are related to operations are additions to or deductions from net income to arrive at net cash provided by operating activities.

A T-account analysis may be helpful when preparing the statement of cash flows. A T-account is set up for each account, and beginning (2002) and ending (2003) balances are taken from the appropriate balance sheet. Additionally, a T- account for cash and cash equivalents from operating activities and a master or summary T-account of cash and cash equivalents should be used.

Example of preparing a statement of cash flows

-

The financial statements will be used to prepare the statement of cash flows.

| 2003 | 2002 | |

|---|---|---|

| Assets | ||

| Current assets: | ||

| $ 29,000 | $ 10,000 |

| 4,000 | 6,000 |

| 9,000 | 11,000 |

| 14,000 | 9,000 |

| 10,000 | 13,000 |

| $ 66,000 | $ 49,000 |

| Noncurrent assets: | ||

| 16,000 | 14,000 |

| 5,000 | 6,000 |

| 5,000 | -- |

| 39,000 | 37,000 |

| (7,000) | (3,000) |

| $124,000 | $103,000 |

| Liabilities | ||

| Current liabilities: | ||

| $ 2,000 | $ 12,000 |

| 9,000 | -- |

| 3,000 | 2,000 |

| 5,000 | 2,000 |

| 2,000 | 1,000 |

| 700 | -- |

| 21,700 | 17,000 |

| Noncurrent liabilities: | ||

| 9,000 | 6,000 |

| 10,000 | 25,000 |

| 4,300 | -- |

| $ 45,000 | $ 48,000 |

| Stockholders' equity | ||

| Common stock, $10 par value | $ 33,000 | $ 26,000 |

| Additional paid-in capital | 16,000 | 3,000 |

| Retained earnings | 30,000 | 26,000 |

| $ 79,000 | $ 55,000 |

| $124,000 | $103,000 |

| Sales | $100,000 |

| Other income | 8,000 |

| $108,000 | |

| Cost of goods sold, excluding depreciation | 60,000 |

| Selling, general, and administrative expenses | 12,000 |

| Depreciation | 8,000 |

| Amortization of patents | 1,000 |

| Interest expense | 2,000 |

| $ 83,000 | |

| Income before taxes | $ 25,000 |

| Income taxes (36%) | 9,000 |

| Net income | $ 16,000 |

Additional information (relating to 2003)

-

Equipment costing $6,000 with a book value of $2,000 was sold for $5,000.

-

The company received a $3,000 dividend from its investment in XYZ, accounted for under the equity method and recorded income from the investment of $5,000, which is included in other income.

-

The company issued 200 shares of common stock for $5,000.

-

The company signed a note payable for $9,000.

-

Equipment was purchased for $8,000.

-

The company converted $15,000 bonds payable into 500 shares of common stock. The book value method was used to record the transaction.

-

A dividend of $ 12,000 was declared.

-

Equipment was leased on December 31, 2003. The principal portion of the first payment due December 31, 2004, is $700.

Explanation of entries

-

Cash and Cash Equivalents—Operating Activities is debited for $16,000, and credited to Retained Earnings. This represents the net income figure.

-

Depreciation is not a cash flow; however, depreciation expense was deducted to arrive at net income. Therefore, Accumulated Depreciation is credited and Cash and Cash Equivalents—Operating Activities is debited.

-

Amortization of patents is another expense not requiring cash; therefore, Cash and Cash Equivalents—Operating Activities is debited and Patent is credited.

-

The sale of equipment (additional information, item 1.) resulted in a $3,000 gain. The gain is computed by comparing the book value of $2,000 with the sales price of $5,000. Cash proceeds of $5,000 are an inflow of cash. Since the gain was included in net income, it must be deducted from net income to determine cash provided by operating activities. This is necessary to avoid counting the $3,000 gain both in cash provided by operating activities and in investing activities. The following entry would have been made on the date of sale:

Cash

5,000

Accumulated depreciation (6,000 - 2,000)

4,000

-

Property, plant, and equipment

6,000

-

Gain on sale of equipment (5,000 - 2,000)

3,000

Adjust the T-accounts as follows: debit Summary of Cash and Cash Equivalents for $5,000, debit Accumulated Depreciation for $4,000, credit Property, Plant, and Equipment for $6,000, and credit Cash and Cash Equivalents—Operating Activities for $3,000.

-

-

The $3,000 increase in Deferred Income Taxes must be added to income from operations. Although the $3,000 was deducted as part of income tax expense in determining net income, it did not require an outflow of cash. Therefore, debit Cash and Cash Equivalents—Operating Activities and credit Deferred Taxes.

-

Item 2. under the additional information indicates that the investment in XYZ is accounted for under the equity method. The investment in XYZ had a net increase of $2,000 during the year after considering the receipt of a $3,000 dividend. Dividends received (an inflow of cash) would reduce the investment in XYZ, while the equity in the income of XYZ would increase the investment without affecting cash. In order for the T-account to balance, a debit of $5,000 must have been made, indicating earnings of that amount. The journal entries would have been

Cash (dividend received)

3,000

-

Investment in XYZ

3,000

Investment in XYZ

5,000

-

Equity in earnings of XYZ

5,000

The dividend received ($3,000) is an inflow of cash, while the equity earnings are not. Debit Investment in XYZ for $5,000, credit Cash and Cash Equivalents—Operating Activities for $5,000, debit Cash and Cash Equivalents—Operating Activities for $3,000, and credit Investment in XYZ for $3,000.

-

-

The Property, Plant, and Equipment account increased because of the purchase of $8,000 (additional information, item 5.). The purchase of assets is an outflow of cash. Debit Property, Plant, and Equipment for $8,000 and credit Summary of Cash and Cash Equivalents.

-

The company sold 200 shares of common stock during the year (additional information, item 3.). The entry for the sale of stock was

Cash

5,000

-

Common stock (200 shares x $10)

2,000

-

Additional paid-in capital

3,000

This transaction resulted in an inflow of cash. Debit Summary of Cash and Cash Equivalents $5,000, credit Common Stock $2,000, and credit Additional Paid-in Capital $3,000.

-

-

Dividends of $12,000 were declared (additional information, item 7.). Only $9,000 was actually paid in cash resulting in an ending balance of $9,000 in the Dividends Payable account. Therefore, the following entries were made during the year:

Retained Earnings

12,000

-

Dividends Payable

12,000

Dividends Payable

9,000

-

Cash

9,000

These transactions result in an outflow of cash. Debit Retained Earnings $12,000 and credit Dividends Payable $12,000. Additionally, debit Dividends Payable $9,000 and credit Summary of Cash and Cash Equivalents $9,000 to indicate the cash dividends paid during the year.

-

-

Accounts Receivable (net) decreased by $2,000. This is added as an adjustment to net income in the computation of cash provided by operating activities. The decrease of $2,000 means that an additional $2,000 cash was collected on account above and beyond the sales reported in the income statement. Debit Cash and Cash Equivalents—Operating Activities and credit Accounts Receivable for $2,000.

-

Inventories increased by $5,000. This is subtracted as an adjustment to net income in the computation of cash provided by operating activities. Although $5,000 additional cash was spent to increase inventories, this expenditure is not reflected in accrual-basis cost of goods sold. Debit Inventory and credit Cash and Cash Equivalents—Operating Activities for $5,000.

-

Prepaid Expenses decreased by $3,000. This is added back to net income in the computation of cash provided by operating activities. The decrease means that no cash was spent when incurring the related expense. The cash was spent when the prepaid assets were purchased, not when they were expended on the income statement. Debit Cash and Cash Equivalents—Operating Activities and credit Prepaid Expenses for $3,000.

-

Accounts Payable decreased by $10,000. This is subtracted as an adjustment to net income. The decrease of $10,000 means that an additional $10,000 of purchases were paid for in cash; therefore, income was not affected but cash was decreased. Debit Accounts Payable and credit Cash and Cash Equivalents—Operating Activities for $10,000.

-

Notes Payable increased by $9,000 (additional information, item 4.). This is an inflow of cash and would be included in the financing activities. Debit Summary of Cash and Cash Equivalents and credit Notes Payable for $9,000.

-

Interest Payable increased by $1,000, but interest expense from the income statement was $2,000. Therefore, although $2,000 was expensed, only $1,000 cash was paid ($2,000 expense - $1,000 increase in interest payable). Debit Cash and Cash Equivalents—Operating Activities for $1,000, debit Interest Payable for $1,000, and credit Interest Payable for $2,000.

-

The following entry was made to record the incurrence of the tax liability:

Income tax expense

9,000

-

Income taxes payable

6,000

-

Deferred tax liability

3,000

Therefore, $9,000 was deducted in arriving at net income. The $3,000 credit to Deferred Income Taxes was accounted for in entry (e) above. The $6,000 credit to Taxes Payable does not, however, indicate that $6,000 cash was paid for taxes. Since Taxes Payable increased $1,000, only $5,000 must have been paid and $1,000 remains unpaid. Debit Cash and Cash Equivalents—Operating Activities for $1,000, debit Income Taxes Payable for $5,000, and credit Income Taxes Payable for $6,000.

-

-

Item 6. under the additional information indicates that $15,000 of bonds payable were converted to common stock. This is a noncash financing activity and should be reported in a separate schedule. The following entry was made to record the transaction:

Bonds payable

15,000

-

Common stock (500 shares x $10 par)

5,000

-

Additional paid-in capital

10,000

Adjust the T-accounts with a debit to Bonds Payable, $15,000; a credit to Common Stock, $5,000; and a credit to Additional Paid-in Capital, $10,000.

-

-

Item 8. under the additional information indicates that leased equipment was acquired on the last day of 2003. This is also a noncash financing activity and should be reported in a separate schedule. The following entry was made to record the lease transaction:

Leased asset

5,000

-

Lease obligation

5,000

-

-

The cash and cash equivalents from operations ($15,000) is transferred to the Summary of Cash and Cash Equivalents.

Since all of the changes in the noncash accounts have been accounted for and the balance in the Summary of Cash and Cash Equivalents account of $17,000 is the amount of the year-to-year increase in cash and cash equivalents, the formal statement may now be prepared. The following classified SCF is prepared under the direct method and includes the reconciliation of net income to net cash provided by operating activities. The T-account, Cash and Cash Equivalents—Operating Activities, is used in the preparation of this reconciliation. The calculations for gross receipts and gross payments needed for the direct method are shown below.

| Cashflows from operating activities | |||

| $102,000 | (a) | |

| 3,000 | ||

| $105,000 | ||

| $ 75,000 | (b) | |

| 9,000 | (c) | |

| 1,000 | (d) | |

| 5,000 | (e) | |

| (90,000) | ||

| $ 15,000 | ||

| Cash flows from investing activities | |||

| 5,000 | ||

| (8,000) | ||

| (3,000) | ||

| Cash flows from financing activities | |||

| $ 5,000 | ||

| 9,000 | ||

| (9,000) | ||

| 5,000 | ||

| Net increase in cash and cash equivalents | $ 17,000 | ||

| Cash and cash equivalents at beginning of year | 16,000 | ||

| Cash and cash equivalents at end of year | $33,000 |

Calculation of amounts for operating activities section of Johnson Co.'s statement of cash flows

-

Net sales + Beginning AR - Ending AR = Cash received from customers

-

$100,000 + $11,000 - $9,000 = $102,000

-

-

Cost of goods sold + Beginning AP - Ending AP + Ending inventory - Beginning inventory = Cash paid to suppliers

-

$60,000 + $12,000 - $2,000 + $14,000 - $9,000 = $75,000

-

-

Operating expenses + Ending prepaid expenses - Beginning prepaid expenses -Depreciation expense (and other noncash operating expenses) = Cash paid for operating expenses

-

$12,000 + $10,000 - $ 13,000 = $9,000

-

-

Interest expense + Beginning interest payable - Ending interest payable = Interest paid

-

$2,000 + $2,000 - $3,000 = $ 1,000

-

-

Income taxes + Beginning income taxes payable - Ending income taxes payable + Beginning deferred income taxes - Ending deferred income taxes = Taxes paid

-

$9,000 + $1,000 - $2,000 + $6,000 - $9,000 = $5,000

-

Reconciliation of net income to net cash provided by operating activities

| Net income | $16,000 | |

| Add (deduct) items not using (providing) cash: | ||

| 8,000 | |

| 1,000 | |

| (3,000) | |

| 3,000 | |

| (2,000) | |

| 2,000 | |

| (5,000) | |

| 3,000 | |

| (10,000) | |

| 1,000 | |

| 1,000 | |

| $15,000 |

(The reconciliation above is required by US GAAP when the direct method is used, but there is no equivalent requirement under the international accounting standards. The reconciliation above illustrates the presentation of the operating section of the cash flow statement when the indirect method is used. The remaining sections [i.e., the investing and financing sections] of the statement of cash flows are common to both methods, hence have not been presented above.)

Schedule of noncash transactions (to be reported in the footnotes)

| Conversion of bonds into common stock | $15,000 |

| Acquisition of leased equipment | $ 5,000 |

Disclosure of accounting policy

For purposes of the statement of cash flows, the company considers all highly liquid debt instruments purchased with original maturities of three months or less to be cash equivalents.

Statement of Cash Flows for Consolidated Entities

A consolidated statement of cash flows must be presented when a complete set of consolidated financial statements is issued. The consolidated statement of cash flows would be the last statement to be prepared, as the information to prepare it will come from the other consolidated statements (consolidated balance sheet, income statement, and statement of retained earnings). The preparation of these other consolidated statements is discussed in Chapter 11.

The preparation of a consolidated statement of cash flows involves the same analysis and procedures as the statement for an individual entity, with a few additional items. The direct or indirect method of presentation may be used. When the indirect method is used, the additional noncash transactions relating to the business combination, such as the differential amortization, must also be reversed. Furthermore, all transfers to affiliates must be eliminated, as they do not represent a cash inflow or outflow of the consolidated entity.

All unrealized intercompany profits should have been eliminated in preparation of the other statements; thus, no additional entry of this sort should be required. Any income allocated to noncontrolling parties would need to be added back, as it would have been eliminated in computing consolidated net income but does not represent a true cash outflow. Finally, any dividend payments should be recorded as cash outflows in the financing activities section.

In preparing the operating activities section of the statement by the indirect method following a purchase business combination, the changes in assets and liabilities related to operations since acquisition should be derived by comparing the consolidated balance sheet as of the date of acquisition with the year-end consolidated balance sheet. These changes will be combined with those for the acquiring company up to the date of acquisition as adjustments to net income. The effects due to the acquisition of these assets and liabilities are reported under investing activities. Under the pooling-of-interests method the combination is treated as having occurred at the beginning of the year. Thus, the changes in assets and liabilities related to operations should be those derived by comparing the beginning-of-the-year balance sheet amounts on a consolidated basis with the end-of-the-year consolidated balance sheet amounts.

[1]Alternatively, interest and dividends received may be classified as investing cash flows rather than as operating cash flows because they are returns on investments. In this important regard, the IAS differs from the corresponding US rule, which does not permit this elective treatment, making the operating cash flow presentation mandatory.

[2]Alternatively, IAS 7 permits interest paid to be classified as a financing cash flow, because this is the cost of obtaining financing. As with the foregoing, the availability of alternative treatments differs from the US approach, which makes the operating cash flow presentation the only choice.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 147