Inter-Organizational Corporate Strategy

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

Figure 3 shows the vertical axis, representing risk (that runs from low to high), against a horizontal axis representing benefits (also runs from low to high). We indicated that an ideal IT project should occupy the space in the bottom right area, showing low risk with high benefits (Checkland & Scholes, 1990). This is because IT projects that are most likely to attract attention and get approval are those that present low risk and deliver high benefit.

However, risks and benefits are not necessarily well-defined dimensions. Advocates of a given IT project or IT-based business initiative will usually play down the risks and talk up the benefits, often with little more to backup their viewpoints than faith in the vision and a burning desire to proceed. Rather than providing a whole variety of mathematical formulas that depend on what you may or may not want to take into account when calculating risks and benefits, we selected the following to summarize the points to consider when trying to calculate ROI:

-

Benefits that come from reducing cost can be different than those that come from increasing revenues. The latter are often estimated optimistically. Any estimate for them must take into account historical precedent and the capacity of the company to acquire the business.

-

Most IT project costs are real, but most expected benefits are less certain. To be realistic, probability factors need to be applied.

-

A time cutoff should be applied when calculating benefits. A rough rule of thumb is that benefits should only be calculated to apply for 18 months after they appear. The longer the time period used here, the more likely it is that something will change to alter the situation. This is especially so when benefits constitute competitive edge.

-

IT projects are risky, and some types of project have fairly high failure rates. However, this varies from project to project depending on what is being done.

In the current economic climate, the desire to take risks is diminished, and the need to cut costs is paramount. Corporations and IT departments are looking for technology propositions that are low risk and likely to deliver a high return quickly on the money invested (Whelan & McGrath, 2001).

ASP in Business Management

Quite often when companies hit troubled times, they attempt to apply the same solutions as in the past, with the same effect. Some may argue that a completely internal consistent solution could still fail, because it is geared toward earlier market conditions. Most take too long to scale down, which severely impacts profitability. Then, they cut back hard, leaving them unable to take advantage of the u-turn when it arrives. Unfortunately, they end up repeating these up and down cycles rather then planning for, and performing well under, bad conditions, and putting themselves in a position to exploit the good times.

Several authors have argued that the successful companies of the future will be inherently more flexible, more distributed, and more fast moving than in the past. Such efforts must also be undertaken collaboratively with partners (Hagel, 2002; Markus, 1983; Tebboune, 2003). It requires moving from traditional supplier and customer relationships to genuine partnerships based on collaborative goal setting. Partners must be engaged in debates on issues covering the following:

-

How can we coordinate our business processes to work together faster?

-

How can we eliminate the bottlenecks that prevent us from getting our products and services to the customer more quickly?

-

What customer information should we share to our mutual benefits?

Instead of the current attitude toward negotiating, as an art of science, adapting businesses should consider negotiation a part of a successful process. An ASP business model involves alliances that are beginning to come far more naturally and should be faster and easier to consummate, because adaptive business networks mandate that companies adopt standard business processes, enabling them to work together more efficiently. Helping a business to adapt to the new age is not an IT process that should be regarded as some sort of IT project. Rather, it is a business process initiative supported by technology (McLeord, 1993).

People Management in an ASP Environment

In the age that IT is seen as a strategic part of the business, most executives have become familiar with jargon such as ERP and e-business, causing IT to enter the cultural mainstream with the advent of e-mail and Web browsers. Many IT directors are part of their firm’s executive team. However, Y2K and the dot-com crash dented the credibility of IT bosses, and budgets were cut back in response to the economic slowdown. The increased focus on business skills means today’s IT directors do not necessarily come from technical backgrounds.

In essence, the inter-organization is a distributed network of human talent. Within individual organizations, outmoded human resources management philosophies must be replaced by modern approaches that maximize the brain contribution to the service, not just the brawn contribution. The emphasis is on working smarter, not just harder. The past three decades of Internet existence have been marked by a long series of brilliant software and methodological innovations that have defined, each time afresh, the scope and content of online socializing, entertainment, electronic commerce, business-to-business transactions, directory services, as well as electronic publications and scholarly interaction. An ASP strategy requires inter-organizations to rethink not just the elements of its economic milieu, but also their political and social contexts. This does not suggest some kind of radical shift away from the profit motive to the quality-of-life motive.

As a strategy that emerged from the spread of the Internet, ASP projects require key attributes for people management in the Internet Age. Some of these are leadership, which involves the ability to form and maintain a good team as well as the ability to “steer the ship.” Vision involves management having the confidence and skills to deploy required new technology throughout the organization. Managers of ASP vendors must also be able to build relationships by having a cohesive line of communication with people at all levels. A certain degree of political skill is required in managing ASP projects to satisfy the need for collaboration with various directorships in the different organization. More important is the ability to deliver, which is the ultimate aim for any ASP management. This often requires the ability to achieve actual results based on meeting customers’ requirements.

Thus, one must agree that these can amount to a tall order for most ASP vendor executives. This is because they are usually from highly technical backgrounds and have very little business management training. They are expected to pick up the relevant skills and succeed in a short period. We must remember that as a programmer trained at university, a prospective manager for an ASP vendor will have been trained to follow rules and has baggage. During the period preceding his or her appointment to management, for example, as a software developer or project manager, he or she would have had very little discretion. Then as manager of an ASP project, one realizes that a manager has lots of discretion and that there are no rules to follow and no right answers. Thus, the ASP executive role has become more focused on business than cutting-edge technology. Some may argue that this has not been a recent change. Other areas such as outsourcing, an IT director’s relationship with the board, systems integration, and value for money are other issues just as pressing (Maslow, 1943).

Managing Business Process with ASP

With the ASP business model, inter-organizations are moving from a data-driven view of business and of IT systems, which tend to be hard-wired and inflexible, to a process-driven approach, which is much more fluid and functional and is designed to cross company boundaries. The emerging view is that, sooner rather than later, managers will be able to change their business processes in the same way that they can currently change data—at a high level, with little technical knowledge and little risk. Many refer to this as business process management (BPM) (Information Age Research, 2003).

There is a need for further research to investigate the practice of BPM in an ASP-implemented environment. Questions need to be asked, whether or not customers understand the terms and the technologies. Are customers buying or implementing BPM along with ASP? Who are the major ASP vendors also selling BPM? This would follow up on a less rigorous survey carried out by Internet Age (Information Age Research, 2003).

Table 3 shows that a cautious approach is needed for ASPs selling BPM due to a rather confused marketplace for BPM. While customers appear to have a good understanding of the possible benefits of moving to some form of process- oriented approach, even if most are not ready to buy, only a quarter of companies are actively using BPM, based on their understanding of the term. Encouragingly, more than two-thirds identify better business agility and control over workflow as key benefits.

| Main Benefits of BPM | Main Benefits of ASP | ||

| Faster application development | 19% | To automate procedures | 16% |

| Better control over workflow | 70% | To link together programs | 15% |

| More business agility | 64% | As a strategic tool for building business agility | 22% |

| Better integration between application | 45% | As an integration backbone | 25% |

| Do not know/no benefits | 4% | For managing processes | 23% |

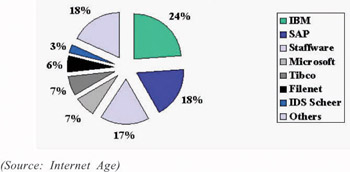

Figure 4: Leading BPM suppliers (Source: Internet Age)

ASP Value Proposition

The value-creating potential of ASP is a critical factor for the success of any ASP business model. In conjunction with the ASP Industry Consortium, a knowledge-based benefits/risks assessment framework was developed that delineates five key performance areas for evaluating the value-creating potential of ASP business models: delivery and enablement, management and operations, integration, business transformation, and client/vendor partnerships (Currie, 2003). In each category, a list of key performance indicators can be evaluated by existing or potential ASP customers. For example, under delivery and enablement, the customer evaluates the importance of receiving an application 24/7 in relation to their own businesses. Customer requirements may vary with this performance indicator, so it is incumbent upon the ASP to evaluate how important this requirement is for an individual customer; 24/7 may be more important to a health-care organization than to a brewery. In another example, management and operations, a customer may adopt an ASP solution because he or she wishes to reduce the total cost of ownership of the IT facility. Using an ASP for collaboration tools may not be done to save money but for reasons of efficiency. Alternatively, a hosted BPR application may reduce the total cost of ownership. The value proposition will, therefore, vary between ASP vendors and their customers. The challenge for ASPs is to understand customer requirements and not assume that all customers want the same things from an ASP solution.

ASP and Business Continuity

While the growth of the ASP market was at its peak by the end of the 20th century, many start-up firms mistakenly described themselves as self-styled ASPs (Currie, 2003). The ASP market quickly became saturated, as ASP became a global phenomenon. Telecommunications firms, with vast IT infrastructure capabilities, needed to partner with SAPs (ISVs and ASPs) to fulfill their aspirations. ISVs and ASPs required the services of data center providers (telecos) to host their software, unless they invested in this capability (most ASPs did not). No doubt we will see a shakeout of ASPs over the next few years, with mergers, acquisitions, and failures (Bender-Samuel, 1999; Hagel, 2002). You may also notice an implicit battle between entrenched classic technology vendors, who are moving conservatively into the ASP scene, and upstarts, who think they see ways to use Internet technology to encourage substantive industry change in work flow, customer service, and sales. Consider the ASPs you see today as a first wave of a more general transformation. It is not reasonable to expect that all databases supporting the services industry (i.e., insurance, banking, airlines, etc.) will be hosted. It is much more likely that within 5 years we will see hybrid environments with some processing and data storage occurring locally and some on remote servers delivered to the point of use in the background (Sleeper & Robins, 2002).

The above conceptual framework was developed to operationalize the constructs of strategic positioning, produce/services portfolio, and value proposition. The attributes pertaining to these constructs and a description of how they relate to the ASP business model is given in Table 4.

| Constructs | Attributes | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Strategic positioning | Industry structure Sustainable competitive advantage Market segmentation Customer focus Market differentiation Firm composition | Determines the profitability of the average competitor Allows a firm to outperform the average competitor Type of ASP (enterprise, pure-play, vertical) Target customer market (large, midsize, or small businesses) Geographical reach (international, regional, national, local) Strategic alliances, partnerships, joint ventures |

| Product and services portfolio | Scale economies Scope of applications Distinctiveness/uniqueness Production/service differentiation | Number of customers needed to make a profit (high volume/low cost or low volume/high cost) Type of products/services offered in relation to degree of standardization/customization (ERP, CRM, e-mail, etc.) Combination of product/services (enterprise, vertical, etc.) Branding, price, bundling, aggregation, switching costs |

| Value proposition | Applications/services outsourcing Value creation for customer Benefits/risks assessment | Delivery and enablement (24/7 service/data security) Management and operations (reduced total cost of ownership) Integration (EAI across departments/sites/borders, etc.) Business transformation (increased agility/BPO/BPR) Client/vendor partnerships (strength through partnerships) |

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 148