GroupwareGroup Support Systems

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

Groupware/Group Support Systems

The term “GSS” first appeared in 1989 (Nunamaker et al., 1989). Since then, the term GSS has become the umbrella term that includes a wide variety of terms designed to support group activities. Information systems to support group activities have been studied under many different names, such as group decision support systems (GDSS), computer-supported cooperative work (CSCW), electronic meeting systems (EMS), collaboration support systems (CSS), group support systems (GSS), computer-supported collaborative work, computermediated communication systems, and group negotiation support systems. The change of the name implies the expanding roles of information technologies and provides a comprehensive set of tools for decision making, communications, meetings, information sharing, etc.

More groupware will be inextricably tied to Internet technology. Many groupware products are integrating more Internet protocols. As of 1999, more than 75 Web groupware products were available (Wheeler, Dennis, & Press, 1999). Many well-known companies such as Lotus, Microsoft, and Novell are developers of Web-based groupware. Furthermore, vendors such as Instinctive Technology Inc., Zap Business Communications Systems Inc., Eastman Software Inc., and even Lotus deliver the thin-client groupware features they need without the expense, complexity, or overhead of fat clients (Gaskin, 2000). Gaskin provided us with several examples of companies that use a new generation of thin-client Web groupware products to communicate with their customers, employees, and virtual team members around the globe. The following cases of Haworth Furniture and True North Communications are condensed versions taken from Gaskin (2000).

Haworth Furniture sells more than $1.5 billion per year worth of furniture products in more than 50 countries with 600 salespeople worldwide. Until they found a solution, they were stuck with e-mail, telephone, voicemail, and faxes. After a comprehensive evaluation of several groupware options, Haworth chose Instinctive’s eRoom to support customers, dealers, installers, and even potential customers who needed access to the information suitable to support field sales operations across every time zone, usually from laptops on the road. One of the primary differences between traditional groupware and eRooms is the focus on the team, especially teams from multiple organizations such as suppliers and partners, customers, and vendors.

Haworth hosts eRoom internally, supporting more than 600 worldwide users on a single server. Called the Global Account Information Network, the system uses more than 300 customer “eRooms,” or collaborative workspaces, that include documents, issues, tasks, and complete discussion lists. Team leaders add or delete members from their own eRooms, making administration simple.

The company sends product announcements, holds sales meetings, and makes presentations, all through eRooms. Employees inside as well as outside the sales department regularly join eRooms to service particular customer needs, such as engineers helping design installations. Haworth field employees reach their eRooms through the Internet or the corporate VPN.

The case of True North Communications illustrates the use of Groupware using mobile technologies. Widespread availability of Internet-enabled wireless devices creates a new breed of e-business conducted in a wireless environment (mobile business).

True North Communications is an advertising conglomerate with 498 offices around the world and is growing rapidly by acquisition. They used e-mail but had no worldwide collaboration system in place. They were working with a nameless vendor and came close to making a system. That is when True North turned to Ucone from Zap: Hosted by Linux running on a Cobalt Networks Inc. RaQ3 server, Zap installed their system in less than 2 days and turned it over to the company. True North then customized their needs and started the rollout. Each office creates and manages its own “toolbox” inside the Zap Ucone software. The toolboxes contain the information for everyone to share.

The system is being used by more than 250 people, scattered throughout the nearly 500 offices around the world. New application opportunities popped up immediately. More than a dozen True North employees had brand-new Palm VII’s and wanted to use them to access the system. Engineers from Zap translated Ucone’s XML output to the brand-new Wireless Access Protocol (WAP). Since Zap uses a standard WAP server for connections, wireless Web telephones and other devices should work when connected. Zap had to write a small Palm Query Application, but nothing changed on the server side. The PQA eliminates the need to type in a specific URL from the organizer.

Workflow Systems

An important information technology for IOSs is a workflow system that needs to be embedded into streamlined, virtual value chains that transcend organizational boundaries. As organizations automate and interconnect their business processes, workflow capabilities are being embedded into most major enterprise application integrations (Margulius, 2002). Workflow systems are business process automation systems that track process-related information and the status of each activity of the business process. They are part of enterprise application integration solutions and business process management, including business activity monitoring and business process automation. The major activity includes job routing and monitoring, document imaging, document managing, supply chain optimization, and control of works. Workflow applications can be classified into collaborative, production, and administrative workflow systems. An IOS focuses on primarily collaborative workflow systems.

Traditional workflow systems were built on departmental server-based architectures. Consequently, they were departmental and forms driven. Now, as workflow engines migrate from departmental server-based architectures to more powerful enterprise application integration (EAI) messaging-based architectures, islands of workflow are starting to get connected throughout the enterprise. Now workflow functionality increasingly becomes part of these broader platforms such as enterprise application integration solutions and business process management.

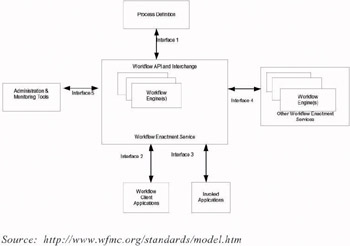

One obstacle for embedding workflow systems into IOSs is the development of interoperability standards for workflow systems. According to Margulius (2002), efforts to develop such interoperability standards as the Workflow Management Coalition have largely failed, although widely accepted terminology (join, router, tasks, etc.) for workflow components emerged. Several organizations were involved in making efforts toward workflow management standards, such as OMG’s jointFlow specification, Simple Workflow Access Protocol (SWAP), and the Workflow Management Coalition (WfMC)’s workflow reference model. Of these efforts, the workflow reference model from the WfMC, even though it only provides an abstract-level architecture, has widely been adopted and used (Yang, 2003). Figure 5 illustrates the workflow reference model from the WfMC (Coalition, 1995). Nevertheless, there has been continuing efforts by big software vendors such as IBM and Microsoft to develop flow interoperability standards including Web Services Flow Language (WSFL) to address the intermingling of machine (straight-through) and human (longrunning) processes.

Figure 5: Workflow reference model diagram

Source: http://www.wfmc.org/standards/model.htm

The Kepner-Tregoe Survey (2000) tells us that information for decision making comes from sources such as e-mails, the Internet, and corporate intranets (Kepner-Tregoe, 2000). The coupling of business processes of telecom partners resulted in shared workflow processes through collaborative telecommunication services (van der Aalst, 2000). Likewise, not only does the Internet provide us with vast amounts of information, but it also enables us to link the whole world together in real time. There are many other technologies available to support data interchange among different standards of technologies. Van der Aalst and Kumar (2003), for example, showed how eXchangeable Routing Language (XRL) using eXtensible Markup Language (XML) can be used to exchange business data electronically.

In categorizing virtual enterprises utilizing interorganizational workflows, Tagg (2001) took into account business needs and natural patterns of cooperative business activity and provided a number of examples, such as formal joint ventures to share risk and skills, informal supply chain with or without dominant player, and end clients with preferred suppliers.

Managers often use information that they capture on inventory, production, or logistics to help monitor or control those processes. For example, GE has used its procurement marketplace Trading Process Network (TPN) in the process of identifying suppliers, preparing a request for a bid, negotiating prices, and making a contract to a supplier. Electronically linked producers, wholesalers, retailers, and consumers will be able to lower their costs by reducing intermediary transactions and unneeded coordination. Even though information technology is now the preferred technology for conducting business transactions and coordinating the business processes, Zhao (2002) pointed out that there are some barriers that have to be overcome by the implementers of inter-organizational workflow management systems:

-

Autonomy of local workflow processing

-

Difference in levels of local workflow automation

-

Variation in workflow control policy

-

Confidentiality preventing complete view of workflow

-

Low interoperability due to heterogeneity in hardware, software, and modeling in multiple organizations

-

Lack of cross-company access to workflow resources (agents, tools, and information)

-

Adaptable workflow processes

The following case of the company AFLAC, taken from Gaskin (2000), shows that Web groupware and workflow systems are being integrated into parts of EAI solutions and business process management.

AFLAC, another company that is using Web groupware, started groupware a decade ago in the guise of electronic filing and document management. The company has been an Eastman Software customer for nearly a decade. The browser gives the company an extra level of flexibility. Employees can work at home, AFLAC associates can enter work items from the field, and even AFLAC payroll accounts can submit work items via the Web. The latest Eastman Software project included placing customer correspondence entered directly on the Web site into the workflow system. Customers wanted information and requested changes, and AFLAC wanted to keep the process paperless while still servicing the customer.

The company’s goal is to pull the information straight from the request entered on the Web site and integrate that into the legacy mainframe system, then send the notice to the workflow system. Correspondence is routed to the appropriate person with the skill set to provide the service. All the routing is managed by a browser client, which is new for AFLAC, but welcomed.

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 148