Decision-Making as a Learning-Supported Process

Even though our understanding of the nature of decision-making as a complex process and a multifaceted phenomenon has come a long way (see for example Langley, Mintzberg, Pitcher, Posada, & Saintmacary, 1995; Mumford, 1999), a persistent issue remains that decisions are based on the information available and the interpretations that decision makers impose as they make sense of the information available. If we accept that decision-making involves a large degree of sense-making (Weick, 1995) then perhaps the challenge is to examine how decision makers learn to make sense of the information they have available, how they use their own knowledge [both tacit and explicit (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995)] in formulating the understanding that then guides their repertoire of assumptions, as well as their actions in relation to taking a decision.

The view of decision-making as a learning-based rather than information-based process is relatively unexplored in the existing literature. The only reference to decision taking as a learning process is made by Arie de Geus (1999) and Ackoff (1999), both of who acknowledge that it is important to understand how learning takes place, however, they do not actually examine what is the relationship between learning and decision-making. In this section we make the case for a learning-based view of decision-making by first discussing the main issues and controversies in understanding the role of learning in the context of decisions. From the analysis we also identify some of the principles of a learning-supported approach to decision-making considering also the role of ICT's and other decision support systems. We begin by reviewing the main modes of learning.

Modes of Learning

The development of learning theory over the years has commanded the attention of many researchers and reflects the emergence of a number of 'schools of thought' each proclaiming to have a better grasp of what learning is and how learning takes place. In an extensive review of the learning theories, Burgoyne and Stuart (1976, 1977) identified at least eight "schools of thought" which they discuss using metaphors in relation to their main principles and applications, as well as, their assumptions about the nature of people. In similar fashion, Merriam and Caffarella (1991, p. 138) discuss four main theories of learning — Behaviourist, Cognitivist, Humanist and Social and Situational Learning — and discuss their main principles in relation to their orientation to learning. Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of each of these theories and the basic assumptions about how adults learn.

| Aspect | Behaviourist | Cognitivist | Humanist | Social and situational |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learning theorists | Thorndike, Pavlov, W atson, Guthrie, Hull, Tolman, Skinner | Koffka, Kohler, Lewin, Piaget, Ausubel, Bruner, Gagne | Maslow, Rogers | Bandura, Lave and Wenger, Salomon |

| View of the learning process | Change in behaviour | Internal mental process (including insight, information processing, memory, perception | A personal act to fulfil potential | Interaction /observation in social contexts. Movement from the periphery to the centre of a community of practice |

| Locus of learning | Stimuli in external environment | Internal cognitive structuring | Affective and cognitive needs | Learning is in relationship between people and environment. |

| Purpose in education | Produce behavioural change in desired direction | Develop capacity and skills to learn better | Become self-actualized, autonomous | Full participation in communities of practice and utilization of resources |

| Educator's role | Arranges environment to elicit desired response | Structures content of learning activity | Facilitates development of the whole person | Works to establish communities of practice in which conversation and participation can occur |

Table 1 shows that the orientation of different learning theories over the years has moved from notions of conditioning and indoctrination, towards autonomy and self-direction. Further realization that learning consists of unstructured, discontinuous and often unconscious aspects has generated more interest in the experiences people in organizations encounter and the actions they take (Marsick & O'Neil, 1999). Experiential learning and action learning theories aimed to address this issue by placing importance on the social, cultural and political aspects surrounding the learning process. This view has found more voice in recent contributions promoting a situated view of learning in organizations, integral to the functioning of communities of practice (see Wenger & Snyder, 2000; Lave & Wenger, 1991). These perspectives have also helped bring to the forefront greater consideration of the psychoanalytic, emotional and aesthetic aspects of learning (see Antonacopoulou & Gabriel, 2001; Scherer & Tran, 2001).

The development of learning theory illustrates the difficulty of capturing the complexity and diversity of learning from any one single perspective. This is best reflected in the lack of an agreed definition as to what learning is. Earlier theories considered learning as a change in behavior, which results from the acquisition of knowledge and skills. Many researchers have actually defined learning in these terms (e.g., Bass & Vaughan, 1966). The definitions of learning assume that the change in behavior is relatively permanent and that practice and experience are an important ingredient. Learning defined in these terms is often associated with taking action towards resolving problems (e.g., Argyris, 1982; Thomas & Harri-Augstein, 1985). However, as researchers increasingly recognized that learning is not always a structured, continuous and conscious process, learning has been defined as a process of gaining a broader understanding and the awareness of the personal meaning of experiences which does not necessarily result from the acquisition of new knowledge as much as a rearrangement of the existing knowledge (e.g., Gagn , 1983; Revans, 1982). Learning has been increasingly defined in broader terms to capture the complexity of thinking, as well as acting and researchers have more recently described learning as a process of reframing meaning, transformation and liberation (e.g., Antonacopoulou, 1998; Kolb et al., 1991; Sch n, 1983). The recognition that learning is a dynamic and emergent process encourages a more integrative framework of interacting variables which arrests learning as a space of action, interaction and transaction than simply a means of filling knowledge gaps (see Antonacopoulou, 2002a). From this perspective, learning emerges from the interconnection of various personal and contextual factors. In other words, learning does not only depend on the individual's motivation and personal drive, but on the reinforcement of learning within the environment as well. This point stresses the situated and contextual specificity of learning and signals that different modes of learning allow learners to use feedback from the interaction with the environment as the basis of improving how and what they learn (see Antonacopoulou, 2002b).

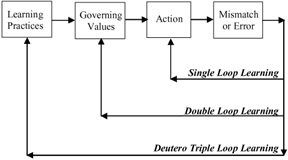

The most widely known modes of learning to reflect this point are the distinctions made by Argyris and Sch n (1974) between single- and double-loop learning and (Bateson, 1972) with reference to deutero or triple-loop learning. These modes of learning are chosen as the focus of analysis because, unlike other types or modes of learning promoted in the existing literature, they have feedback loops at their core. Figure 1 represents diagrammatically the three modes of learning.

Figure 1: Three Modes of Learning

Essentially, it could be argued that single-loop learning is predominantly concerned with identifying and correcting a problem and depending on the consequences if the problem persists, because the actions taken failed to address it, then one has to consider alternative actions. Double-loop learning on the other hand, still propounds a problem-solving mentality at the core of learning activity however, unlike single-loop learning it seeks to detect and correct a problem but also modify underlying norms and objectives, which have guided the implementation of the initial action. Finally, deutero (triple-loop learning) is concerned with learning to learn. Learning does not stop when a problem is solved or when new actions are taken to prevent it from happening again, nor is it enough to review ones assumptions. One must also actively seek to reflect, inquire and develop new strategies for learning. Romme and van Witteloostuijn (1999, p. 439) echo this point when they suggest that while double-loop learning "involves reframing … [and] learning to see things in new ways," triple-loop learning requires "developing new processes or methodologies for arriving at such re-framings." In triple-loop learning not only are norms questioned, but embedded assumptions of how we think and learn are re-examined.

From this brief overview of learning modes it is evident that the main difference between them lies at the level one seeks to use feedback as a means of rethinking whether one's actions in relation to why one learns (e.g., solving problems or taking decisions) are also consistent with how and what one learns. These issues are perhaps better evident in the role of learning in supporting a range of organizational processes such as decision-making.

The Relationship Between Learning and Decision Making

It is increasingly recognized that a number of key organizational processes have learning at their core. de Geus (1997) propounds the view of planning as learning, while Whittington (2001) explores strategizing as [learning] practice. In this chapter we make the case for decision-making as learning-supported considering that decision-making itself, as others have already argued, entails several learning principles.

Decision-making has been described as a "knowledge-intensive activity with knowledge as its raw materials, work-in-process, by-products and finished goods" (Holsapple, 2001). Yet, to-date we have limited empirical evidence that shows what forms of knowledge constitute the process of making decisions, how such knowledge is produced and utilized, how different stakeholders formulate their knowledge, and what impact the different knowledge they bring has on the process of decision-making. These issues suggest that a key priority in understanding the nature of decision-making is to understand first the way knowledge that serves decision-making purposes evolves as different human, technological and social conditions interact and create conditions that shape the nature of decision-making. Therefore, we need to move beyond the view of decision-making as a step process based on knowledge components, to understand decision-making as a complex process of learning possibilities.

One of the key principles critical to decision-making is feedback. This suggests that at the core of making a decision lies knowledge and insights gained from past and current experiences which can affect significantly the kind of decision made, as well as the way decisions are reached. Beach (1990) supports this view in his 'Image Theory', showing how decision-related knowledge influences how a decision is made. Beach identifies three distinct but related images: the decision maker's values and principles (image 1); his/her goals and agenda (image 2); and his/her plans, tactics and forecasts (image 3) about what (s)he expects (s)he will accomplish from the decision. Therefore, one's mental models are not only restrictive of one's ability to make decisions they are also restrictive of one's ability to learn.

This reveals an intimate relationship between learning and decision-making. In the same way that learning is a necessary requirement for decision-making, decisions have to be made to create learning. This would seem to be at the core of what decision-making as a learning-based process could be all about — namely that decisions are possibilities that are shaped by the purpose they seek to address. This means that in the same way learning is contextual and situated, decision-making is particular and idiosyncratic to the actors (people and social dynamics between them) and structures (systems that define the boundaries of interaction between social actors, e.g., technology) involved with shaping the purpose of decision-making. Feedback mechanisms are critical in balancing the known with the unknown. Based on these principles the next section examines how ICT systems can be employed as feedback mechanisms capable of codifying knowledge and conducive to learning-supported decision processes.

ICTs for Supporting Learning-Based Decision Making

Despite the common perception of a decision support system as a particular tool, the widespread view is that "the term decision support system is an umbrella term to describe any and every computerized system used to support decision making in an organization" (Turban & Aronson, 2001, p. 14). The concept has evolved from management information systems in the '60s and '70s through to expert systems and group decision support systems in the '80s to data warehouses, business intelligence tools and portals in the '90s (Power, 2002).

Our understanding of how such technologies are used in organizations has improved over the years. Researchers and practitioners developed frameworks that highlighted the behavioral aspects of decision support technologies and explored the information needs of decision makers (Simon, 1960; Gorry & Scott Morton, 1971; Davis, 1974; Sprague & Carlson 1982). A significant milestone came with the development of expert systems and artificial intelligence tools. These technologies enhanced the knowledge-based capabilities of decision aiding tools (Silverman, 1994).

While the users of traditional decision support systems are usually expert decision makers, the users of intelligent decision support systems that incorporate expert systems technology can be novices. They range from non-experts that need advice or training, to experts that seek the advice of an expert system to validate their own opinion. Only a small number of expert systems replace rather than support decision makers (Edwards, Duan, & Robins, 2000). In decision analysis applications, the intended users of intelligent tools include the facilitator, the actors, and the D.I.Y. users who directly interact with a decision-aiding tool (Belton & Hodgkin, 1999). Depending on their education, training, expertise, beliefs and experiences different decision makers reach decisions and apply actions to different levels of success (Turban & Aronson, 2001). As Marakas (2002) points out there is not currently a bandwidth limitation between a network and a computer but rather between a computer interface and the brain of a decision maker.

A new generation of decision support tools such as data warehouses and data mining was introduced in the '90s. Companies have implemented data warehouses and employed data mining and business intelligence tools to improve the effectiveness of knowledge-based decisions and gain competitive advantage (Heinrichs & Lim, 2003). Other primary decision support systems include OLAP (Online Analytical Processing) and Web-based decision support tools (Shim et al., 2002). Executive (or enterprise) information systems allow managers to drill down into data while offering highly interactive graphical displays (Bolloju, Khalifa, & Turban, 2002). Intelligent agents and strategic decision support systems support the formulation of strategy and improve organizational performance (Carneiro, 2001). Collaborative systems offer facilities ranging from supporting groups of decision makers to coordinating virtual teams (Shim et al., 2002). All these technologies can become available on the Web to reduce costs, allow easy access to information and therefore improve efficiency. In this context, ICTs such as intranets and extranets can be constructed to provide decision support (Power, 2002).

The preceding paragraphs show that decisions support systems offer a diverse range of functionalities. They support decision making at different levels ranging from acquisition, checking and display of data to interactive evaluation and ranking of alternatives (French & Papamichail, 2003). The aim of this section is not to provide an exhaustive list of decision aiding tools but rather to illustrate how such technologies can be used to enhance learning in decision processes. Using the same classification of modes of learning given in the previous section, we discuss how different types of decision support systems support the three modes of decision-learning.

Single-loop decision-learning. A wide range of tools can be employed to facilitate the implementation of decisions through better knowledge and understanding of the decision context and content. For example, databases and on-line sources offer easy access to explicit forms of decision-related data. Executive information systems and other business intelligence tools such as OLAP products and visualization packages, provide on-the-fly data analysis so that managers become aware of problems and monitor the implementation of their strategies. Expert systems support control activities such as monitoring, diagnosis, prescription and planning. Data mining techniques (e.g., artificial neural networks, genetic algorithms, rule induction, case-based reasoning) convert raw data into more meaningful and actionable forms of knowledge by finding patterns in historical data and learning from past examples (see for example Bose & Mahapatra, 2001).

Another technology that can facilitate learning through inferences from history is an experience database that contains decision problems or opportunities that ended in failure or success. Such databases can be coupled with case-based reasoning (Shaw, Subramanium, Tan, & Welge, 2001) or rule-based system tools (Hunter, 2000) to facilitate the retrieval of cases or identify partial matches. Their main contribution is that they allow individuals to learn about past decisions, as well as respond to the challenges of the future without reinventing the wheel or repeating mistakes (Croasdell, 2001).

Single-loop technologies improve actions through access to repositories of explicit knowledge and better understanding of the decision problem. Even though they promise to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of decision-making, it is important to acknowledge their limitations. Walsham (2001) gives the account of the manager of a multinational company who described the intranet of his company as a large warehouse that nobody visits. Organizations need to give incentives and motivate individuals to access repositories and learn about new ICTs.

Double-loop decision-learning. A common decision rule that individuals adopt when they are unable to reach a decision is to get an expert to explore the decision problem and provide them with a briefing (Janis, 1989). In such a setting, directories of experts or 'people finder' databases can be particularly useful. Eliciting expertise from one or more experts, however, requires interaction (Huber, 2001) and ICTs that support this include e-mail, online chat, mailing lists, newsgroups and on-line conferences.

If experts are not available, expertise is scarce in a domain, or there is the need to elicit and permanently archive the experiences of valued employees then 'lessons-learned' systems should be considered. They differ from experience databases that codify information about a decision problem because they capture expertise and meta-knowledge (e.g., the reasoning behind a decision and the company's agreed values and beliefs that justified a particular decision). Orr's (1990) ethnographic study of Xerox's maintenance engineers is an illustration of this point.

As decision makers are facing time and space challenges, computer-supported collaborative environments promise decision-making teams to perform tasks faster, more accurately, and with fewer resources (Maybury, 2001). They provide services such as workflow management and shared applications, as well as, a variety of facilities including text chat, audio-and video conferencing, shared whiteboard and shared and private data spaces. Such systems enable parallel or serial interpretations of data by experts who interact synchronously or asynchronously to extract, process and disseminate information to decision makers. However, these technologies are platform and software dependent, the users have to enter a specified online place and the group members are not always aware of other participants and their activities, which inhibits communication and group work (You & Pekkola, 2001). Therefore, collaborative environments have not been successful in decision environments that require negotiation and knowledge sharing (Walsham, 2001).

Knowledge that flows from different sources contributes to collective meanings (Croasdell, 2001). In large organizations, it is important to integrate knowledge sources and provide a knowledge map that binds the knowledge components together (Preece et al., 2001). Concept maps, semantic networks and frames (Liaw & Huang, 2002) can also overcome information overload problems.

Single-loop technologies make knowledge retrievable whereas double-loop technologies contribute to learning by making meta-knowledge and individuals with decision-making expertise accessible. Advanced collaborative support tools can increase decision-making interactions. The collective experiences of individuals provide background knowledge for understanding decision-making processes, policies, culture, and practices, and could therefore improve the effectiveness of decision making (Croasdell, 2001).

Deutero decision-learning. Communicating knowledge through an electronic medium does not necessarily improve human communication and action (Walsham, 2001). Online data and knowledge repositories, e-mail messages and newsgroup archives cannot always codify the deep tacit knowledge that is needed for decision-making. Most companies are starting to realize that levering knowledge through ICTs is not always attainable (McDermott, 1999). Face-to-face interactions that allow participants to give and take meaning by interpreting a range of verbal messages and nonverbal clues, as well as mentor relationships between new and experienced recruits can enhance the continual inter-subjective communication between decision makers (Walsham, 2001). Electronic media such as video conferencing and on-line chat can be used to create virtual teams and eliminate the need for some expensive face-to-face meetings (Maznevski & Chudoba, 2000). Virtual teams however, cannot outperform face-to-face teams in terms of communication effectiveness and their members report lower levels of satisfaction compared to face-to-face team members (Warkentin, Sayeed, & Hightower, 1997).

Reaching a consensus in a group of decision makers is often difficult to achieve. Individuals have to convey their thoughts, understand the viewpoints of their colleagues, and interpret other people's mental models. Thus, it can be argued that decision-making is the result of a learning process in which a community of people develops a common language, deals with a context-specific issue, and has a specific purpose and reasons about actions. Organizations ought to acknowledge, support and nurture these 'communities of practice' that encourage knowledge sharing, learning, and change (Walsham, 2001; Wenger & Snyder, 2000). Participants of communities of decision-making practice will share ideas, experiences, and know-how, and will adopt innovative and creative approaches to problem-solving and decision-making. This can prove to be an effective way of sharing deep decision-making knowledge.

From this overview, it is evident that there are a number of well-established ICT tools and approaches that support decision-making by facilitating knowledge transfer and feedback. Therefore, ICTs could potentially play a vital part in stimulating and supporting feedback mechanisms between actors and structures affecting decision-making and learning. Their fundamental contribution perhaps lies less in the codified knowledge they can transfer and more in the momentum they can create so that awareness of learning opportunities can be acknowledged and integrated in the decision-making process. Moreover, ICTs can be a valuable mechanism for capturing and extending the current organizational discourse (Grant, Keenoy, & Oswick, 1998). These points are central to the socio-technical framework of learning-supported decision processes discussed next which emphasizes feedback systems as the social structures that support knowledge flow in organizations.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 198