4.1 A Sense of Presence

4.1 A Sense of Presence

Unlike medieval people, we do not have a sense of presence in today’s society. We are growing more and more detached from our families, workplace and friends. The latest surveys of the millennium generation (post-generation X) indicate that although teenagers are striving for individualism, they are searching for a sense of belonging to a social group. The Internet has given many individuals a new sense of presence by connecting them with people who share a common interest. In Zachary’s words:

Science and technology innovations are giving people the power to make over their identities, and they are using them. To what extent people can figuratively and literally reinvent themselves through a combination of computer simulations, computer-human mergers, biomechanics, bioelectronics and genetic engineering is more a matter of speculation that reasoned debate.[120]

We live in a world governed by our interactivity with the physical elements of our daily life. Technology now permits interactions that are representative of physical actions, such as controlling remote devices. Thus technology offers interactions that are clearly detached from the physicality of the action, such as creating an electronic agent that acts on one’s behalf in cyberspace. Actions, transactions and interactions that represent your connection to the digital world reflect your cyberbehaviour and call into question how an individual is present in the new digital inform- ation age.

Technology is enabling the average person to experience a new global citizenship in which the traditional boundaries of geography, religion, culture and government are undergoing a redefinition as a direct result of technological advancement. Using technology, our fundamental relationship with activities previously associated with work transforms our notion of when, where and how these activities are performed. Similar to the knights of the Round Table’s quest for the Holy Grail, technology companies are striving to create the universal information appliance, a device that transforms information and access to and/or from any device. Using this device (conceivably wearable), interactions can be facilitated universally. That is to say, it is a device that acts as your primary interface between the physical and digital (or virtual) world.

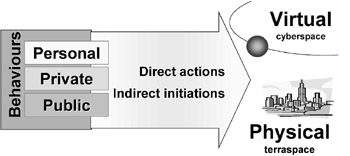

In order to put this device into a greater context of how one is present in the digital information age, the characteristics of socio-technological behaviour must be addressed. Individual behaviour in the physical world (terraspace) and virtual world (cyberspace) can be classified into three broad categories of interactivity: public, private and personal, as depicted in Figure 4.1. Individuals in terraspace and cyberspace share a common set of actions as a result of their two-way interaction with others:

-

personal, in which the action or infrastructure that surrounds the action is not to be shared, or shared only with a small, intimate audience

-

private, where the interaction and data are shared with a selected organization or group of individuals

-

public, where the action, data and other attributes are generally available to anyone.

Figure 4.1: Categories of interactivity

Transactions are the product of a direct action or indirect initiation by a customer. Direct actions such as an individual actively making a purchase occur via interactive gateways such as PDAs, PCs, or bar-code scanners. Indirect actions are those carried out by an intelligent agent responding to a prescribed set of conditions laid down by an individual, such as triggering a stop loss order to your brokerage when a particular set of shares drop below your preset limit. Another type of indirect action is where a person is caught speeding by a camera and the fine is directly debited from their bank account. Both direct and indirect activities must be facilitated by a mechanism, a mode or a method of delivery, and usually are representative of a state of mind.

Of course, a person could easily behave in one way in the physical world, and yet behave in another way in the cyberworld. For example, a person could create a false identity on the Internet to purchase pornographic material digitally, not wishing to reveal his/her true identity, while in the physical world he/she would never dream of purchasing such material in a bookshop because of social pressure. The Internet reduces the physical distance to products, but can decrease the bond with society. It could be said that the Internet provides that same level of anonymity as living in a large city. The ability to construct your own identity on the Internet raises the question of ethical digital behaviour and the extent to which one develops a cyberworld reputation. Moreover, the virtual reputation carries the same or greater risk of being misused or misappropriated by persons unknown to you in the organization.

Apart from the potentially dark side of technological advancements such as the Internet, PDAs, biometric devices, wireless communications and other new high-tech toys, the value proposition they present to technophiles, technologists and the rest of the technology-adept world is clear and easily understood. These devices offer convenience, timeliness and simplicity in interacting with the ever-increasing plethora of digital products. The key is the seamless interaction with many devices, reducing the number of interfaces that an individual must learn. The transitional nature of technology, discussed throughout Chapter 1, means that each new generation of technologies – and indeed any manufacturer’s device – will require learning how to use a greater number of commands, key clicks and set-up features. For those of us who have not yet mastered our VCR programming, the universality of these devices means they only need to be mastered once.

It is interesting to note how the designers of these technologies describe their use, as in the following scenario: while on holiday, sitting on the beach on a Caribbean island, you can use the device to instruct your VCR at home to record your favourite television show, check to see if your house is OK, and order milk and eggs from your local grocery shop to be delivered on the day of your return. The most striking aspect of this future scenario is that it is devoid of technological foresight, that is, it is designed to emulate only today’s behaviour. Firstly, it subscribes to the notion of the old television broadcast model, where one must wait until a programme is transmitted by the network. In this day and age, one should be able to go to the TV network website and simply order the programmes one would like to watch. Secondly, it assumes that, while on holiday, one wants to be continuously connected to the environment from which one is actually escaping. Finally, it assumes that everyone waits until the last minute to do everything, while we are evolving into a society which plans nothing and seeks instant gratification. Cynicism aside, the promise of this technology is that it offers uniformity in the heterogeneous world of digital devices; conceivably, it will increase the rate of adoption in all technologies that subscribe to this universal protocol.

These devices enable an individual to extend themself by initiating activities, collecting information, collating data and conducting transactions on behalf of the user or in agreement with the user’s intentions. For example, if the device recognized a behaviour pattern in the user (such as the type of book read), it could identify these books, rank them, search the Internet for the best prices and, based on these criteria, present the suggested books to the user for acknowledgement, and, after agreement, placing the order on his or her behalf, completing the transaction with credit/debit card information. The most integrating aspect of these devices is their ability to learn and record one’s behaviour. It is through this process of feedback that an individual will modify his or her physical and virtual behaviours to reflect their connections in the digital society. The proliferation of mass media communications technology coupled with the Internet make market differentiations possible, allowing consumers greater choice in highly specialized areas of products and interest. This specialization of interest is fostering a narrowness of focus in special interest groups, comprising popular social movements like anti-globalization, nationalism and religion.[121]

Conversely, in the early media hype of the Internet one would have thought that cybersex was the greatest thing since the invention of electricity, until it was realized that the girls on the Internet were really male computer nerds logging on with female usernames. Their logic was that with a female username you would be more likely to engage another female in conversation and start the seduction process. The big joke was there were many 20–35-year-old men trying to seduce each other. On the other hand, pornography does have a presence on the Internet, but not as rampant as the media would like us to believe. A recent study concluded that the vast majority of pornographic sites required a major credit card to acquire anything that was not readily available on cable television. The role technology plays in providing seemingly transparent access to indecent material is discussed in section 5.4. The key may be in restricting opportunity, not access, by proactively making people aware of the consequence of their actions. For example, if you knew that whatever you watched on television would be printed in the newspaper the next day for everyone in your town to read, would you change your viewing habits?

Now that we have moved beyond the hype about Internet growth, corporations are starting to use the Internet as a viable medium of exchange, and a new sense of presence is needed. Individuals are less likely to attach their username to a piece of questionable correspondence travelling through a corporate firewall with the chance it could be traced back to the source. Developing an understanding of individuals’ actions in cyberspace and their associated behaviours is key to assessing the types of product that can be enhanced, sold or merely facilitated by a combination of new technologies that have been categorized as eCommerce enabling.

[120]G. Pascal Zachary, The Global Me (London: Nicholas Brealey, 2002) p. 16.

[121]Walter Truett Anderson, ‘The Self in Global Society’, Futures, Vol. 31, Number 8, (1999) p. 804.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 77