1.4 The Intent of Technology

1.4 The Intent of Technology

How society adopts and uses technology is frequently not as the technology inventors had intended. Contemporary futurists and other technology prognosticators ponder on the Internet’s ultimate influence on business. Their predictions will, in many cases, be wrong or in some cases half right. Nicholas Negroponte of the MIT Media Lab predicted that by the year 2000 more people would be entertaining themselves on the Internet than watching programming broadcast on network television. In some niche demographic market segments, he may be right, but the majority of the population has not yet moved toward the new medium.[30] However, Negroponte brilliantly surmised that due to the capabilities inherent in the Internet, changing customer behaviour towards self-service and a reassessment of personal time management, individuals would begin to regard television differently. Negroponte stated the ‘the key to the future of television is to stop thinking about television as television. TV benefits most from thinking of it in terms of bits.’[31] This observation does reveal that our behaviour adapts to the new technological capabilities, as witnessed by users of TiVo[32] who overwhelmingly choose to download television programmes and watch them at times which are convenient to them, jettisoning the television network programming schedule altogether.

Another historical example is the original express intention behind the use of television, which was showcased at the 1929 World’s Fair. Television was presented as the technology that would bring a college education to everyone in the privacy of their own home. Early adopters rapidly embraced television as an entertainment medium, and television programming has matured over the years from pure enlightenment to sheer enjoyment. A quick channel surf through today’s hundred-plus cable offerings finds that television’s most recent role is that of the continuous merchandizing of products, now incorporated within the programmes themselves in addition to the commercials. In fact, educational programme channels are in the minority, very different from the original intention.

Neil Postman describes this transitional intention of technology as the passing of a baton between one generation of technologies and another:

We can imagine that Thamus would also have pointed out to Gutenberg, as he did to Theuth, that the new invention would create a vast population of readers who ‘will receive a quantity of information without proper instruction … [who will be filled] with the conceit of wisdom instead of real wisdom’; that reading, in other words, will compete with older forms of learning. This is yet another principle of technological change we may infer from the judgment of Thamus: new technologies compete with old ones – for time, for attention, for money, for prestige, but mostly for dominance of their world-view. This competition is implicit once we acknowledge that the medium contains an ideological bias and it is a fierce competition, as only ideological competitions can be. It is not merely a matter of tool against tool – the alphabet attacking ideographic writing, the printing press attacking the illuminated manuscript, the photograph attacking the art of painting, television attacking the printed word.[33]

One could argue that each successive technological leap does not simply replace the previous technology, but also offers an alternative to a pre-existing coordinal use of technology. For example, television has not replaced the written word because reading a book is a different experience altogether. In many cases, the solitary aspect of reading combined with the seemingly personalized dialogue between the reader and the author is, to some individuals, a more intimate experience when compared to that of the television. Needless to say, television, movies and books present individuals with no more than portals into experiences, values, beliefs, adventures and knowledge of people of other cultures, crossing social barriers of age, race, religion and political persuasion, geography and time itself. The value in the intent of technologies that offer new avenues of communication such as the Internet, television, radio and books is not found in the mechanism used or the method of delivering the communication. The true value of these technologies is that they facilitate a dialogue and enable individuals to acquire knowledge in a medium that is most conducive to their personal learning style. That said, Internet learning, CD-ROM and other technologies are not conducive to all types of learning. It could be argued that there is very little corroborating evidence to validate these technologies as an effective and value-adding way of learning.

The transitional nature of technology, especially information systems and end-user interaction devices such as PDAs, laptops and mobile phones, reinforces the statement that technology is temporary and its half-life of use is proportional to its perceived value by the individual or organization using it. Therefore, any given technology used by business must be viewed in the same light as a liability, not an asset. I have argued elsewhere that technology provides organizations with the opportunity to rethink the products or services that they offer, how they are delivered and, more importantly, why a product or service offering is valuable to a customer. In the case of organizations embracing new technology and applying it wisely, their value propositions are presented with a dilemma, as devices are perceived to have a decreasingly effective lifespan. The longer term implication of the application of technology is to consider putting aside our view of technology as an asset and begin to manage it as a liability. The management of technology should be as if its value declined over time, which it does. In order to put this concept into perspective, the legacy of information technology is rooted in the high capital equipment cost of an investment with a useful lifespan, requiring maintenance and support personnel. Thus the typical classification of technology should be ‘an asset which depreciates over time and provides a mechanism for improved information flow’. However, technology is advancing at an accelerated rate, making older technology not only less valuable, but costly to maintain. Despite the rapid decay of technological value, technology is still regarded as an essential asset of the organization, without which it cannot function. The idea of treating technology as a liability is not an oversimplification of the balance between technology investment and technology deployment; it is merely to say that now technology should be viewed and managed in ways different from those in the past.[34]

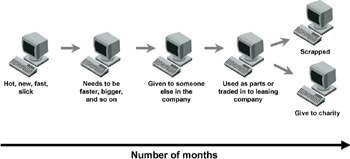

If one takes personal computing as an example of technological transitional value, it can be observed that two distinct social behaviours have developed with regard to hardware and software. A technology user’s attitude follows a pattern in which the underlying number of months is controlled either by personal preference or corporate policy. In information-intense organizations where computational speed and data retrieval time command a premium, it can be observed that the effective lifespan is shorter on the left side of Figure 1.5. Typically, the initial purchase is for the primary user, who will justify passing the technology to the next user in the corporate ‘food chain’ based on a justifiable requirement. The process continues throughout the corporation until the hot personal computer – without which the original user could not live – finds its home with the car parking attendant tracking parking permits, or is subsequently discarded due to higher maintenance cost. US corporations are finding it increasingly harder to give away old PCs to schools and charities because it raises the level of complexity and cost to integrate many makes and models of equipment into existing infrastructures.

Figure 1.5: Software life cycle (PC)

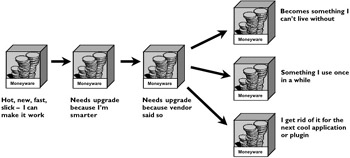

However, the behaviour of software companies is strikingly different from that of hardware companies, as seen in Figure 1.6. The initial motivation in acquisition is the same, but as individuals invest their time in learning the application, they develop one of three attitudes towards the product. It becomes indispensable, occasional or disposable. Firstly, indispensable applications typically exhibit characteristics that facilitate one’s lifestyle (such as Microsoft Money and Quicken, which allow people to control their finances). The amount of time invested coupled with the transactional data accumulated over time makes switching to a package offered by another vendor undesirable simply on cost. Electronic mail is another example of software in which the relearning is hard, but the incompatibility between filing cabinets and address books makes it impossible to switch.

Figure 1.6: Hardware life cycle (PC)

On a historical note concerning eMail, one of the tools used to develop a picture of a historical period is correspondence via private letters, personal papers and other tangible evidence of communications. In their electronic form, eMail that is sent and received today will be irretrievable ten years from now. This raises concerns when we consider that future generations may not be able to retrieve any record of conversations which happened last month, this week or today. It may be prudent to print out some eMails and paste them in a scrapbook just to preserve some evidence of your personal contacts at one point in your life. At the same time, eMail makes communication a lot easier, and people tend to be very clear and ‘to the point’, whereas private correspondence invariably requires more time to write and thus presents more detail. One way or another, what we can observe is a generation of individuals who do not communicate by letter, and whose writing skills are getting less and less powerful due to spellcheckers – which sometimes do not even allow you to err, correcting your grammar errors as you type. If there is a positive side to using computers as text-editors, the loss of writing ability is certainly to be seen as a negative side.

Secondly, occasional software comprises those applications with a highly specialized function which an individual needs only occasionally or which were acquired because of a temporary need. Many of us could not wait to get software that would allow us to make and edit our own videos until we realized what a time-consuming process it is. Today, some people will only use the software package when they have a large amount of leisure time. The third category of software is that of disposable or temporary applications, which in many cases were acquired either as a whim or for a specific purpose. These applications are often ‘lead ins’ to more advanced software capabilities. For example, one can purchase a low price architectural drawing application and, once one has learned it, one realizes the need for a professional version, so abandoning the original program. All these behavioural factors lead to the temporary nature of technologies that are closely associated with the end-user. In this case, the similarities of the technology to a liability are magnified by the volatility of the refreshment rate.

Technology as a Liability

The character of technology as a liability can be seen in the following example: there is a fundamental difference between the strategies of an equities fund manager and those of a bond portfolio manager. Both specialists are managing assets; however, their strategies were born from two very different philosophies on investing. Taking these conditions into account, the management of the technology liability will be different from core back-office systems to end-user or consumer devices. If one considers that consumer retail delivery devices (such as PDAs, PCs, WAP phones and many others) will continue to undergo a high turnover due to the nature of the innovation of devices and consumers’ demand for new technologies, it can be concluded that the delivery of retail banking products using these technologies will have a much shorter half-life than a core processing system. Simply, the rate of the half-life of technology is proportional to the distance to the end-user. Core systems are replaced at a rate of five to ten years, whereas retail end-user technologies range from six months to four years.

The key issue to consider when a company manages technology as a liability is that each technology should be handled based on its application to the business process that it serves and linked to a realistic expectation of a phased retirement. Again, the closer a technology is to a consumer, the faster the rate of decay and the greater the tendency to ‘overmanage’ the asset. For example, a consultant was engaged to review the operating cost of the technology group within a large bank in New York City, and found an ongoing cost of warehousing a stockpile of outdated PCs because they were a depreciated asset. The cost of warehousing these non-functioning computers added to the cost of the labour associated with inventorying and tracking these assets was greater than the new replacement value. Therefore, not only was money being spent on keeping these unusable PCs, they were also purchasing new ones.

So, what is the end state of the Internet and how will it add value as a medium for commerce? In 1975, it would have been next to impossible to foresee the interconnected technologies of today. It is just as impossible today to predict the next generation of technologies. However, reviewing the history of our relationship with technology over the last 70 years, it is clear that the trend in our use and expectations with regard to technology remains consistent:

-

people will adopt and use technology

-

technological adoption occurs at rates often governed by dissociated factors

-

people want to be connected or linked to others

-

people will be mobile

-

convenience carries a premium

-

people need to feel in control.

That said, these observations are general and very broad, but they do provide a window into technology’s basic value proposition and the ways in which it alters the creator’s original intentions over time. Individuals find value in technology when it fulfils a primary need such as mobility, convenience or timeliness in the pursuit of both business activities and actions associated with customers’ lifestyles.

[30]P. Barwise, ‘The Value of the Digital Prophets’, Financial Times, April 23 (2002) p. 5.

[31]N. Negroponte, Being Digital (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1995) p. 48.

[32]TiVo is a digital video recording system equipped with a hard disk that automatically finds and records broadcasted programmes for playback at a later time. Available at http://www.tivo.com.

[33]N. Postman. Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology (New York: Vintage, 1993) pp. 16–19.

[34]J. DiVanna, Redefining Financial Services: The New Renaissance in Value Propositions (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002) p. 237.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 77