Summary - Key Lessons for Managers and Consultants

-

The best IT projects involve using recent, but still familiar, technology for new ends. Web-based and wireless technologies undoubtedly offer unparalleled opportunities to link people and organizations together, irrespective of their location or existing software. But technology does not have to be state-of-the-art for it to be used imaginatively.

-

Finding ways to meet the often divergent needs of multiple stake-holders is a better guarantor of success than trying to override them. Users who think their interests have been neglected rarely have any desire to make a new system a success. However, the willingness to compromise and change has to be tempered with the need to get things done. Among organizations anxious to avoid the long-drawn-out implementation cycles of 10 years ago, the speed with which a system can be completed is crucial to management commitment, user acceptance and benefits realization.

-

Old-style IT consulting would sit uncomfortably with this brave new world, and the last decade has seen significant changes in the way IT consultants work as a result. In place of armies of consultants that still haunt client memories from the 1990s, have come smaller teams, working side by side with client staff. While a small number of consultants play a longer-term coordinating role, the majority are used only when necessary, where the client lacks a particular skill.

-

But it is momentum, above technical knowledge and working style, that clients still put at the top of their agenda when it comes to working with IT consultants. As projects become more complex, both in technical and human terms, the need to have some means by which energy is injected has become fundamental to success.

Tracking persistent offenders through a shared case-oriented system is part of an initiative to ensure that fewer criminals slip through the justice net. Multiple agencies and viewpoints have been reconciled in an application that ties together different components of the Criminal Justice System and delivers tangible results to the public.

Dealing with crime and its effects on the community is high on the agenda of any government. We judge the health of our society by our sense of personal security, and we judge society's development by the quality of its justice. Justice famously needs to be seen to be done. With the increasing sophistication of policing methods and the continued development of the law, those who manage to evade justice stand out as challenges to the system. Offenders who are not brought to justice offend the public's sense that we are in control of the social environment, and that the values we hold are universally honoured.

Recognizing the stubborn and highly visible nature of this problem, the UK Criminal Justice System created a strategy called Narrowing the Justice Gap. The strategy was to bring together all the agencies dealing with the problem of bringing offenders to justice, and particularly the most persistent offenders. Speaking at the launch of the strategy in October 2002, the Home Office Minister for Criminal Justice Reform Lord Falconer said:

The CJS [Criminal Justice System] has halved the time it takes to deal with persistent young offenders from arrest to sentence. Building on this work, an early focus of Narrowing the Justice Gap is a strategy to clamp down on adult persistent offenders by bringing them to book for more offences and making them give up their life of crime. Home Office research shows that 100,000 criminals are responsible for half of all recorded crime and increasing the frequency of an offender being caught and convicted is the most effective single way of shortening their criminal career.

The strategy is implemented through the Persistent Offender Scheme, launched in February 2003. The scheme's aim is to target the most prolific adult offenders. These are individuals who have been convicted of six or more recordable offences in the previous year, together with other offenders identified by local police intelligence.

Progress had already been made in dealing with persistent young offenders. In 1997 the government announced its Persistent Young Offenders Pledge to halve the time it takes to sentence persistent young offenders from the time they were arrested. The pledge was due for delivery by May 2002. The government calculated that in 1996 dealing with a persistent young offender took an average of 142 days. The pledge was in fact met by June 2001 when the time was cut to only 69 days, beating the government's target by 2 days. This performance has since been consistently sustained.

A key element of the new Persistent Offender Scheme was to be the introduction of a new IT tool. This new Web-based system, called JTrack, would easily identify for criminal justice agencies those prolific offenders who met the new persistent offender definition, and also allow police locally to flag up their persistent offenders. These offenders are responsible for a range of crimes, including theft, burglary, and crimes of violence such as robbery and criminal damage. JTrack would also enable these offenders to be tracked by the police and Crown Prosecution Service (CPS).

The police would be able to use the new tool in conjunction with local intelligence systems including the National Intelligence Model in order to identify and prioritize those offenders having six convictions in one year and other prolific offenders that need to be targeted locally. When these offenders are caught, the criminal justice agencies will give priority to their cases to ensure that they are brought to justice for as many of their offences as effectively and speedily as possible. This ‘premium service' was already being piloted in the areas covered by the government's earlier street crime initiative and became a core component part of the Persistent Offender Scheme.

Lord Falconer went on to say:

Too few offenders are brought to justice. In 2000-01 over 5 million crimes were recorded by police but in only 20 per cent were offenders brought to justice. The current size of the justice gap is unacceptable, we can and must do better. Narrowing the Justice Gap is a key measure of the effectiveness of the Criminal Justice System and a crucial indicator of success in reducing crime.

JTrack was to be an important driver for the Persistent Offender Scheme, and was intended to help spur further improvements throughout the justice process. Yvette Cooper, Minister at the Lord Chancellor's Department added:

We have already made progress in cutting delays, in particular halving the time from arrest to sentence for persistent young offenders, but over 50 per cent of trials still do not start on time. This causes unnecessary stress for victims and witnesses and increases the risk that cases may collapse completely. We are developing new measures to set out the timetable for trials, and provide incentives for defence and prosecution to get cases ready on time.

A new multi-departmental team called the Justice Gap Action Team (JGAT) was created to act on behalf of the three UK government departments responsible for overseeing the Criminal Justice System (CJS) in England and Wales: the Home Office itself, the Department for Constitutional Affairs and the CPS. In May 2002 JGAT asked PA Consulting Group to help create JTrack and deliver the system by 1 April 2003. A combined JGAT/PA team, working with all the relevant partner agencies, designed, developed and implemented the system in under six months. JTrack is now improving levels of collaboration between the country's 43 police forces and 42 CPS areas.

A multi-agency system

The first multi-agency application of its kind in the UK, JTrack is a Web-based system hosted on a secure network accessible by over 2,500 authorized users throughout England and Wales. The various agencies use the same set of information to manage crime and provide real-time management information. JTrack enables practitioners in the police and CPS to track the progress and results of cases from arrest to finalization in a consistent way, including not only persistent offender cases but also street crimes. Within four months of its implementation, there were already over 42,000 offences on the system. Work is under way to consider extending JTrack to other agencies such as the Probation Service and the courts.

The application mirrors the development of case-oriented systems in the business world. This type of system is a workflow response to the fragmented nature of the information held about an enterprise's customers. The focus of case-oriented systems is the progress of a piece of information-intensive work that requires the attention of a number of different specialists at different stages and in different organizations.

In the commercial environment, established organizations have traditionally suffered from fragmented views of their customers. Customer information is distributed among a range of different business systems, and aggregating data is cumbersome and expensive. Since businesses grow in response to market demand, it is natural that they develop systems in response to new opportunities, rather than for the purposes of improving overall management understanding of the customer base.

In the past, a company contemplating the launch of a new product would build a new system to support delivery of that product. Similarly, a company reaching out to a new market segment would design a new system for that business stream. At the same time company mergers and acquisitions frequently enlarge the number of logically overlapping systems in the organization.

One answer to this problem is to create a common view of the customer via a data warehouse or using a collaborative layer that brings together data from disparate systems. However, this approach tends to produce retrospective information, which may be excellent for business development purposes, but rarely helpful in serving customers directly. Customer-centric systems are therefore now built to support customer service under the banner of customer relationship management (CRM). CRM applications typically support call centres and other customer touch points where the initiator of any event is the customer rather than the enterprise.

Case-oriented applications solve the fragmentation problem in a different manner. The driver of this class of business systems is the standard work-in-progress that unites the various teams involved in pursuing the business goal. In a city planning office, for example, the central work-in-progress is the ‘planning application'. This is a growing body of documentation incorporating plans, proposals, amendments, surveys, citations and consultations. The efficiency and effectiveness of the planning department depends entirely on its ability to manage the throughput of each case, ensuring that each dimension of the work is addressed in a complete and timely manner.

In the justice system, different agencies will measure their effectiveness in different ways, such as by offence, offender or case (which may have multiple offences and offenders). Part of the challenge of JTrack was to construct a system that could capture information in a consistent way across all agencies but present the data in a format that staff in agencies could understand.

Every case-oriented application calls for careful attention to the multiple complex requirements of the different teams involved on progressing the core work in progress. PA used its rapid systems development (RSD) methodology to capture requirements and deliver the project on time. RSD is an iterative technique that involves users and other stakeholders in the design and development of a system from day one. Consistent user involvement and application prototyping are at the heart of RSD, so the methodology ensured that all stakeholders' requirements were taken into account throughout the development process.

Threading the multi-agency web

The JGAT/PA team and its partner justice agencies quickly agreed the need to track persistent offenders across the criminal justice system so that all agencies could tackle them effectively. Agencies also required real-time access to consistent management information at both national and local levels so their performance could be effectively monitored.

There were, however, significant obstacles to providing the necessary information. First, the existing local case management systems could not track persistent offender cases across agencies, or provide consistent up-to-date local and national management information. Each system was an island of information.

Second, the only potential national source of management information was the Police National Computer. However, this system could not provide information where it was needed most - at the local level - since it was primarily designed as an operational system rather than a management tool, and had no reporting capabilities.

The team next found that the various agencies used different means of counting crimes. Some counted offenders while others counted cases that might involve several offenders and crimes. These inconsistencies made it impossible to measure cross-agency effectiveness, with no common method of measuring how successfully agencies were dealing with persistent offenders.

The fourth obstacle encountered by the team was located in the existing organizational schedules. Current strategic programmes to ‘join up' the different agencies of the Criminal Justice System would not deliver for at least three to five years. The Persistent Offender Scheme needed a solution by 1 April 2003, the formal start of the scheme and the date from which its performance targets would apply. The team would somehow have to square these conflicting timelines.

Fifth, the team had to deal with an absence of key performance indicators (KPIs). Because of the deadline set for the project, the new solution would need to be built while KPIs for the Persistent Offender Scheme were being defined. The time constraints also ruled out some of the standard approaches to systems development in a complex environment. PA's Andrew Hooke explains:

Developing a system to track persistent offenders was a gap in the market, as it were. This system is bringing new information into the process. At the feasibility stage you normally look at making enhancements and linkages to existing systems. But because we were driven by the time frame, only a bespoke system, built from scratch, would do. Then we'd need to ensure the appropriate linkages with other systems as part of ongoing maintenance work.

Lastly, a poor track record of IT delivery within the Criminal Justice System had made local users understandably cynical about new IT initiatives. They were unwilling to commit to using new systems, and JGAT had no powers to force them to do so.

Overcoming the obstacles

Meeting the project's deadline was the key determinant in the team's choice of approach. The team used PA's RSD techniques to develop the system through an iterative prototyping process. RSD made it possible to have a version of JTrack ready for piloting within just eight weeks. Working with selected police and CPS users, the development team subjected this first pilot version of the system to intensive review, testing and redevelopment.

The team then exploited existing communications networks to make the system accessible to all agencies without the delay inherent in implementing a new IT infrastructure. JTrack was hosted on the Criminal Justice Extranet (CJX), a secure national infrastructure. This was the first time that the CJX had been used for such an application.

Although identifying the CJX as a route to delivering the system was a distinct benefit to the project, obtaining the required hosting permission within tight timescales was a challenge in itself. Any system has to be formally accredited by the Police Information Technology Organisation (PITO) prior to its use on the CJX. However, since the CJX had not been used for a cross-agency system, there was no clear accreditation path. The team worked closely with PITO and secured accreditation in under six months, an impressive turnaround given the vast scope of the system.

When it came to measuring business performance, the team had to make JTrack flexible enough to accommodate the different counting rules used by the police, the CPS and other agencies, while providing the consistent means of measurement required by the Persistent Offender Scheme. JTrack was therefore designed to use offences as its core measurement unit, but offers the ability for users from different agencies to view and input information in the way they are used to, whether by case or by offender.

The team also recommended that JTrack be designed to track street crime cases, and thereby replace local tracking systems. The system was built with these requirements in mind and all street crime areas have subsequently migrated to using JTrack.

To make the system as flexible as possible in use, the team gave JTrack many optional elements that can be turned on and off to suit different users. For example, the system can be used to track local priority groups of offenders, as well as the nationally defined persistent offender and street crime groups, thus meeting both national and local performance reporting requirements.

JTrack can generate a range of performance reports at divisional, area and national levels, as well as enabling areas to compare their performance with other areas. In addition, users can easily and flexibly download subsets of the database to undertake their own performance analysis. PA's Hooke stresses that communicating the local and national benefits of the system was crucial to developing a system that would be usable, and used:

You have to look at the system from at least two dimensions. The first is meeting the government's requirement for a central view and measuring progress in meeting national initiatives. The second is that you've got to provide something of use to local practitioners. The position is: I'm not coming here with a centrally driven initiative - my primary aim is local management information that will help you manage your business. Then the local people take more interest, they begin to buy into the project, and they're more ready to build the KPIs.

The RSD methodology helped the team respond to changing user requirements during the project's life cycle. The Persistent Offender Scheme was changing as JTrack was being built. Halfway through the development, it was decided that the Persistent Offender Scheme needed extra flexibility to allow for local definitions of persistent offenders. RSD enabled the team to respond quickly to these developments, while safeguarding core functionality and respecting delivery commitments.

The system was developed using Web technology and XML, a means of creating, storing and processing self-describing data. This architecture makes JTrack easy to maintain and enhance.

The methodologies and technologies chosen by the team ensured the technical capability and quality of JTrack. But even the best-designed systems can founder in the face of user disinterest. Intensive user involvement was critical if JTrack was to be accepted by its diverse user base spanning 43 police forces and 42 CPS areas. Fortunately the RSD methodology allows users to drive the direction and scope of the development process. The team established a core group of users who, together with Home Office and CPS national representatives, helped to define how JTrack would work and look, down to the level of individual page layouts. In this way the team ensured that from day one JTrack's design was informed by the real needs of users.

Working closely with the system's target users allowed the team to define extra features that increased JTrack's usefulness to local users. For example, the system includes an interface with the Police National Computer so that it can transmit details of persistent offenders to JTrack every month. This feature enables users to track offenders not only in their own area but also in adjacent areas. While the representative users effectively drove the development process, the team kept all stakeholder groups abreast of progress and helped them prepare to connect to, and make effective use of, the system. As the go-live date approached, the team trained more than 1,500 users, completing the process within 10 weeks. This training played an important role in convincing local users that the system could help them in their work.

As the cases flow, the justice gap closes

JTrack was ready for roll out by December 2002, just five months from the start of the formal development project in July and a month ahead of schedule. Take-up of the system was enthusiastic. All areas were connected to JTrack and had started to use it by 1 April 2003. As of 1 July 2003, there were 2,358 users and 42,960 offences on the system.

In August 2003, JGAT commissioned a review to evaluate the first few months of the Persistent Offender Scheme. Initial reaction to JTrack was that it was a good system. The majority of users found it straightforward and simple to use. Managers were beginning to take advantage of the rich and comprehensive data now held on JTrack. In particular, several areas said that JTrack was a valuable management tool for tracking local priority offenders.

JTrack is, of course, not an end in itself. Its true value lies in its contribution to the overall process of reducing crime rates, bringing more criminals to justice and so building greater public confidence in the justice system. JTrack is helping progress towards these objectives by providing a real-time tool that coordinates the agencies' efforts and provides shared visibility of actual progress. JTrack is encouraging effective joint working at a local level. For the first time, agencies in the criminal justice sector are able to share common data with one another. While accommodating each agency's preferred ways of working, JTrack provides consistent local and national measurement. Users can now compare their performance regarding persistent offenders and street crime with achievements in other parts of the country. Performance data is now available daily and monthly for all areas. Previously this information was either not available at all, or was at least six months out of date.

The team's achievement in bringing the system to delivery in such a complex organizational environment is recognized by those within the IT community. The Head of Information Systems & Technology at Durham Police says:

This has been one of the smoothest IT projects I have been involved with for a long time. PA's contribution was key to this smoothness. By using the firm's own flavour of rapid applications development, PA managed to reconcile different needs, opinions and worries by centring the project on the production of a usable system. This allowed the team to progress issues constructively and demonstrate progress through successive iterations of the system, rather than tackling a cumbersome process made up of meetings and documentation.

PA also demonstrated a highly valued attribute of the best consulting practices: the ability to go beyond the formal scope of the project when needed. John Kennedy, JGAT's project manager, recognizes that making the system available on the existing network was a major plus point: ‘PA also provided support above and beyond remit by helping us select the hosting provider and successfully negotiating CJX accreditation.'

Significantly, the system's contribution to the fight against crime is also recognized at the sharp end of policing. A detective inspector with Hampshire Police says: ‘This is the first system where volume crime offenders are captured in one net. Each area now has the opportunity to pick the most prolific offenders and concentrate on dealing with them proactively and effectively.'

It is fitting that a network of cooperating agencies has been able to use Internet technologies to help close the net on the UK's persistent offenders. As a result, the criminal justice system is on its way to meeting its target of bringing 1.2 million offences to justice by 2005-06.

The Mayor of London's ambitious plan to unclog the city's streets triggered one of the world's most complex and pressurized projects. The targeted use of practical methodologies and a can-do attitude got the work done on time, and London's traffic is flowing once again.

Roads form one of the modern world's scarcest and most fought-over resources. While the fuel that powers our vehicles is continuously won from the earth with ingenuity and care, often miles from where we live and work, the roads we drive on do not expand to match our appetite for travel. Road scarcity is no more pronounced than in the world's great cities, where accommodation may grow vertically, but surface transportation is constrained. Old cities with peculiar, evolved street patterns fare worst from the relentless onslaught of traffic. London's millennial traffic crawled at the same average pace achieved by horse-drawn carts a century earlier, and vehicles typically spent half their journeys waiting in queues. The impact of slow-moving traffic on the environment was particularly obvious in London's new tradition of summer photochemical smog - ‘peasoupers' to rival the fogs its clean-air Acts had banished from the winter scene in the 1950s. And road congestion was calculated to cost the city's business community some £2 million every week.

The concept of charging for road usage has been circulating in policy circles since at least 1951, when economist Milton Friedman co-wrote an essay in which he proposed charging road users a fee ‘in proportion to their use' of the highway. While this proposal is perfectly in line with free-market thinking, its political implications made decision-makers steer clear of it. Pricing road usage as a means of manipulating demand clashed with the ideals of personal liberty represented by car ownership. Governments had invested in the development of the automobile industry and in roads infrastructure through general and specific taxation. To bar drivers from the road system they had paid for was, for generations, a step no politician was willing to take.

Ken Livingstone, the first elected Mayor of London, made the concept of congestion charging for the central London area a major element of his campaign for office. Livingstone had shown during his leadership of the now defunct Greater London Council (GLC) that he was not afraid to apply pricing mechanisms to the city's transport system. The GLC's ‘Fares Fair' scheme of the mid-1980s for the Underground system was ruled illegal, but not before causing a measurable improvement to services. This time around, the pricing mechanism had been cleared by central government in 1999. The Mayor's Transport Strategy of July 2001 promised a central London charging zone by February 2003.

The objectives of the overall two-and-a-half-year plan were to:

-

reduce traffic levels by 10 per cent to 15 per cent;

-

reduce congestion by 20 per cent to 30 per cent;

-

generate net revenue for investment in public transport;

-

achieve a habitual shift from private to public transport.

From an academic theory that horrified elected representatives to a working scheme on the ground, impacting (and even impeding) the lives of millions of Londoners - within two years. Could it be done? The complexity of the task created one of largest and most publicly scrutinized risk management challenges the world has ever seen.

A sense of volume

Deloitte was hired to programme manage the creation and roll-out of the congestion charge scheme. The firm's team would work closely with management at Transport for London (TfL) and sit above the many other service providers needed to deliver congestion charging, and be involved right the way through to delivery. A key responsibility was technical assurance of all the various elements being procured and deployed for the scheme. The team was therefore acting as a source of continuity for a programme containing many diverse elements as well as performing a quality assurance role. The programme management challenge can be summed up in a handful of numbers. Deloitte designed eight work streams articulating over 430 projects, representing more than 45,000 separate tasks needed to deliver the scheme on its set launch date of 17 February 2003.

The scale and complexity of the delivery responsibility becomes clear when we appreciate the physical, political, and cultural dimensions of the scheme. In the first place, the congestion charging zone would cover an area of 21 square kilometres, containing some of the most obscure road patterns built. The zone would create a new entity on the map of London, and impose a new border. Many thousands of vehicles would flow across this permeable barrier every day, and each would have to be accounted for.

An occupying power might simply impose the charging scheme on the citizenry, in the historic tradition of roadblocks. But this scheme was being implemented by London for London. There would be an 18-month consultation process, running from the announcement of the strategy right up until the last practicable minute prior to launch of the scheme. The consultation process was designed to include presentations, public meetings and public exhibitions. In the event the debate also continued in the local, national and international media. A legal challenge from Westminster City Council (WCC) also led to the scheme's consideration (and approval) in the courts. Communication with London's many stakeholders was crucial to the success of the scheme, both during its development and ultimately for its smooth operation after launch. The resulting public communications exercise was the largest seen in the UK since the ‘Ask Sid' campaign for the privatization of British Gas.

Tollbooths would have added to congestion rather than reducing it, and electronic methods for charging vehicles were nowhere near ready for market. To make the scheme work, a network of more than 600 enforcement cameras, both fixed and mobile, would have to be installed. These would be sited at 174 access points on the zone's boundary as well as at roadside sites throughout the zone. Camera images would be fed to interpretative systems that would in turn cross-refer to databases of payments. Taken together as a system, the monitoring element of the scheme became Europe's largest camera and telecoms procurement contract.

The scheme's designers estimated that around 200,000 vehicles would use the zone each day. Each single instance of a vehicle crossing the zone's boundary would be monitored and checked against its payment status. The technology needed to read vehicle registration plates and relate them to vehicle databases had already been proven in the ‘ring of steel' around the City of London. However, the business processes and systems needed to take payments from drivers had no single working precedent that could be scaled up to the new challenge. Making it easy for Londoners to pay was paramount to the scheme's design. Although there would be penalties for those who refused to pay, the primary purpose of the congestion charge scheme was to influence road usage rather than generate defaulters. In order to make the payment options as broad and inclusive as possible, a wide number of methods were introduced including via SMS text messaging. No one could predict how many people would use this latter channel. In the event 12 per cent of users chose to pay in this way at the start of the scheme, rising to 19 per cent within three months.

The scheme also entailed the use of building an EPOS (electronic point of sale) retail terminal network running in over 200 central London stores. There would be a further 1,500 outlets within the orbital M25 motorway, and more than 7,000 other locations throughout the UK. More than 100 self-service payment machines would be located at destination car parks. Fleet operators would have their own post-payment solution.

While the pricing mechanism proposed by Friedman provides the central rationale of the congestion charging scheme, the project would also involve a number of micro-measures to further improve traffic flow. The project created the largest traffic management scheme in Europe, designed to ensure that traffic flows at its maximum possible speed and volume while minimizing any negative effects at the boundary of the zone. In Westminster alone, the initiative generated a clutch of management mechanisms including automatic traffic monitoring sites streaming real-time data on traffic volume and speed, new bus routes with new double-length ‘bendy' buses, and a mass of new road signs and markings. The London Traffic Control Centre (LTCC) was set up by TfL to provide real-time information on traffic levels around the capital.

Monte Carlo in London

The project was delivered not by developing new technologies, but by using proven technologies in innovative ways and on a scale never seen before. The main challenges to the project's success therefore lay in the mix of activities, their interdependencies, and the unpredictability of their interactions. Deloitte saw risk management as the key theme for the programme's successful delivery through to launch.

Monte Carlo modelling is an analytical technique for solving problems by performing a large number of trial runs or simulations. Solutions are inferred from the collective results of the trial runs. Another way of defining the technique is as a method for calculating the probability distribution of possible outcomes. The name Monte Carlo was coined during the Manhattan Project of World War II, based on the similarity of statistical simulation to games of chance.

The team used Monte Carlo techniques to model the risks in the programme's costs and duration. This approach enabled the team to visualize the project's potential outcomes and direct attention to likely hotspots before they flared up. Pertmaster and @Risk software (a product of Palisade Corporation) were used to run the simulations and analysis for both cost and duration factors. Further analyses were run during the evolution of the implementation plan so that the team could understand the critical risks around key milestones. The results were fed directly into management actions to mitigate failures.

As the project progressed, risk management was used as a major communication tool, especially prior to the launch. Deloitte consultants developed a bespoke risk database with a Web-based front end, so that risks could be captured centrally but communicated and managed remotely by each appropriate team.

The project team worked with the 33 London boroughs, particularly those with roads in or around the boundary of congestion charging, to mitigate the impact of changing traffic patterns. This involved coordinating approximately 400 traffic-related schemes. As well as formal methods of risk management, the team used a direct, hands-on approach that Deloitte's Chris Loughran calls an ‘invasive' programme management style. He explains the approach in this way: ‘A passive style of programme management focuses on evaluating what people achieve, not what they do. The invasive approach involves looking inside the black box and assessing the processes. It does sound painful… but it's really a combination of carrot and stick.'

Such a technique needs to be used with sensitivity. Deloitte ensured that access to documentation and the right to audit outcomes and processes at key stages were written into every supplier contract.

Complementary skills and shared views

The complex nature of the congestion charging scheme meant that a large number of different specialisms were required at different stages of the project. For example, specialist engineering firms were involved in the design of traffic management systems, while networking experts were needed to design the communications structure between the traffic cameras and the data centre.

While the individual components of the solution were proven technologies, their combined use was novel. Orchestrating the delivery of the overall programme therefore presented some unique challenges to the team. Loughran says: ‘There were some core methodologies that were tried and tested, but they only went so far. This was a large and multi-disciplinary programme - from public contractors to the funding of complementary traffic schemes, through to cameras and enforcement arrangements. There was no 'cookie cutter' set we could use.'

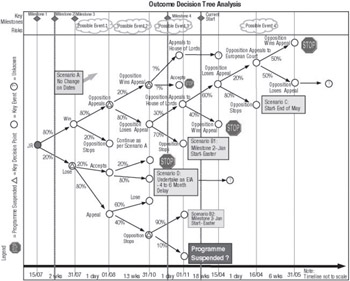

Figure 7.1: Outcome decision tree analysis for contingency planning (Williams and Parr, 2004)

Deloitte therefore had to deploy a flexible, multidisciplinary team to match all the specialisms involved in the delivery that the client could not provide from within its own staff. With the responsibility to assure each element of the implementation, Deloitte needed to deploy experienced professionals as and when they were needed, with each individual hitting the ground running. Loughran estimates that of all the many Deloitte people who have been involved with the project over almost three years, only five have been with the programme continuously. Sharing the project's scope, direction and issues was therefore crucial for continuity through time as well as for the current completeness of the management view.

A current, comprehensive picture of the project's status was provided by a programme strategy chart, a device introduced to the management process early on by Deloitte. The chart enabled the TfL/Deloitte team to track individual work streams while maintaining a sense of the programme's overall shape. The chart also acted as a focal point for the reporting, analysis and actioning of all progress, making it a proactive engine of the project's advancement.

Day-to-day management of the programme was further bolstered using a Business Severity Forum. Programme managers, client and suppliers met daily to review the current issue log. Current problems and their status were brought together from all work streams so that the joint team could agree on the severity and priority of each. The team could then address the most significant issues in the correct order, protecting the critical path of the programme. In this way the principal stakeholders maintained a live, accurate and objective watch on progress. Potential show-stopping issues were identified, communicated, prioritized, fixed and retested in a very rapid cycle.

Breaking the wave

The primary challenge faced by TfL was to develop a politically acceptable and operationally practical policy for a project without precedent, in an environment full of uncertainties. It was difficult to predict the response of the public and key stakeholders. Intense media interest meant that every decision was challenged.

While London would wake up to congestion charging on a set date, the programme team introduced as much as possible of the new scheme ahead of its formal launch. The ‘big bang' planned for 17 February 2003 was preceded by careful foundation work. The preparation for the start date was spread over six months to reduce last-minute activity by the public. The team was keen to avoid what the team called a ‘bow wave': a sudden rush of registrations that might swamp the systems. Residents and other discount holders were able to register for the congestion charge scheme well in advance of its launch. Incentives were introduced for early registration and discount applications.

A thorough testing strategy meant that the scheme had been run in trial mode for some considerable time prior to launch. Elements of the scheme's implementation could readily be tested in isolation. For example, live data capture and analysis from the network of cameras could be tested and tweaked without any charging mechanism being in place. Loughran says: ‘We couldn't stop London - but we could capture live data from the cameras and test that. We could test the plate recognition routines and so on. So the go-live was not really a single event.'

The only element of the scheme that could not be tested ahead of the go-live date was public reaction. Three days before the launch, the Mayor predicted there could be difficulties. Most pundits predicted utter chaos. As no traffic management scheme of this type and scale had been implemented before, no one knew for sure what would happen. With the world's media watching, day one was critical to the success of the congestion charge. The team geared up for the anticipated storm by modelling a range of potential scenarios and putting the necessary processes in place to deal with them if they occurred.

In the event, even the most hostile of observers had to admit that the big bang was remarkably quiet, as traffic died back, payment systems worked as planned, and London went to work.

Assessing the outcome

All major milestones of the scheme were achieved to plan - including the concept design, procurement, technical design study, building and testing - against a timescale described by observers on a scale from ‘challenging' to ‘unachievable'. The congestion charge quickly improved central London's traffic congestion issues, with a measurable increase in passenger numbers on buses and trains:

-

Initial traffic levels entering the zone were immediately reduced by 25 per cent, pulling back to around 20 per cent after the first two months.

-

Congestion plummeted by over 30 per cent during charging hours.

-

The number of vehicles driving within the zone fell by 16 per cent.

-

Journey time on a round trip to and from the zone dropped by 13 per cent.

-

Around 100,000 people were paying the congestion charge on a daily basis (excluding fleets).

In its report Congestion Charging: Six Months On (23 October 2003), TfL summarized the scheme's performance to date, including these achievements:

-

Traffic data, payments data and survey information all pointed to new settled patterns of travel.

-

Traffic delays inside the charging zone had now reduced by about 30 per cent, which was towards the high end of TfL's expectations.

-

Drivers in the charging zone were spending less time in traffic queues, with time spent either stationary or travelling at below 10 kilometres per hour reduced by about one quarter.

-

Journey times to, from and across the charging zone had decreased by an average of 14 per cent. Journey time reliability had improved by an average of 30 per cent.

-

Traffic management arrangements had successfully accommodated traffic diverting to the boundary route around the congestion charging zone.

-

About 60,000 fewer car movements per day were now coming into the charging zone. TfL estimated that 20 to 30 per cent of these had diverted around the zone; that 50 to 60 per cent represented transfers to public transport; and that 15 to 25 per cent represented switching to car share, motorcycle or pedal cycle, or other adaptations such as travelling outside charging hours or making fewer trips to the charging zone.

-

Public transport was coping well with ex-car users. Extra bus passengers travelling to the charging zone were being accommodated by increased bus network capacity.

-

Excess waiting times (an indication of the time that bus passengers have to wait above that expected if the route was operating as scheduled) had reduced by over one third on routes serving the charging zone, partly as a consequence of reduced congestion and increased bus services.

-

Congestion charging was expected to generate £68 million for the financial year for spending on transport improvements, and £80 million to £100 million in future years.

There have also been numerous intangible benefits to London as a result of the scheme, including the following:

-

Pollution has been reduced.

-

Noise has been reduced.

-

Buses now run more reliably, with shorter journey times, resulting in improved timetabling.

-

Road safety has improved.

-

Emergency services are reporting improved response times.

The first anniversary of the charge's introduction was marked with the announcement that TfL had towed away or clamped 255 vehicles, while 40 persistent offenders had had their cars crushed.

The success of this project is principally due to collaborative effort. Deloitte provided a multi-disciplinary team of consultants to work with TfL in fully integrated teams. This worked so well that senior TfL management commented that Deloitte team members were indistinguishable from their own staff.

Commitment to the project was extremely high. Everyone involved recognized they were involved in a project that would have a significant impact on public policy around the world. Through the TfL/Deloitte team's dedication, a genuine ‘can do, will do' culture developed. The collaborative style of teaming also paved the way for a smooth transition from the project team to TfL staff, who assumed responsibility for managing the service provider after the project went live.

Deloitte's key contribution to the project was its versatility. The ability to provide the right mix of professionals at the right time while maintaining continuity in the core team ensured that TfL had the support it needed at each point. While the larger consultants can all claim extensive portfolios of skills and experience in their workforces, applying those qualities successfully in a real project situation is not always a given. The factor that helped above all to engage Deloitte's capabilities in this project was the symmetry between the attitudes of colleagues from the consulting firm and its clients. Loughran says: ‘Our flexibility comes from being in a high-profile, high-pressure environment. It's what we're used to. There's no standing on ceremony, people are 'can-do'. They get the job done. But this characterizes the client too. We had very complementary styles.'

Derek Turner, former Managing Director of Street Management at TfL, says that the consultants' involvement was crucial to the programme's success:

We could not have done this project without consultants, and our confidence in Deloitte was well placed. Their passion and drive for this project helped it to stay on track and deliver benefits to London. The days are gone when a consultant borrows the client's watch to tell him the time.

Ken Livingstone, Mayor of London says: ‘This is the most talented group of public servants that I have ever worked with.'

Congestion charging has had a long political journey from abstract concept to concrete realization. TfL and Deloitte have ensured that millions of smaller journeys will now be less painful for London and its citizens and businesses. This is the way that the circulation of the 21st century metropolis will be reinvented.

Taking a procurement solution to the pockets of decision-makers has saved this organization time and money while preparing it for the coming generation of mobile healthcare applications. But the key aspect of this case is not technology: it is the combination of enforcement and empowerment that is ensuring the promised benefits of a streamlined supply chain really do happen.

In 2002 Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust embarked on a comprehensive supply chain re-engineering programme to streamline its processes, reduce supply spend and operating costs. The project took almost 18 months to complete, involving as it did every part of the organization, from clinical staff through to those working in the hospital's delivery bays. The project has produced significant savings in purchasing costs as well as substantial product standardization and consolidation of the trust's supplier base. Process efficiency has been improved while clinical risk has been reduced.

All these benefits have been achieved within a cultural change in the way that clinical staff think about purchasing. The responsibility of buying the stocks that the hospital needs to treat patients has moved as close as possible to the people who use those stocks. They can now order supplies from personal, mobile devices, cutting through the long paper chase that used to apply. As a result, the hospital's performance is becoming faster, cheaper, safer and more accountable. The project also lays the foundation for further advances in the trust's processes.

The Bradford trust spends in the region of £53 million every year on supplies. The items it buys cover nearly 250,000 stock and 48,000 non-stock items ordered from a catalogue of 10,000 different product lines. Stock items are typically the day-to-day items used on the wards and departments and are managed by a team of materials managers, whereas non-stock items are more ad hoc and can include special devices, such as implants, that must be ordered uniquely by a qualified clinician for each patient that needs them. While nonstock items make up a numerical minority in the overall shopping basket, these items often have a high value in both money terms and their contribution to treatment of patients.

Atos Origin's David Whatley observes that in many NHS trusts there is a tendency to move many items into managed stock in order to simplify the procurement and logistics process. However, a procurement process for non-stock items will always be needed. Bradford took the path of migrating as many stock items as possible to materials management, while empowering clinical staff to order non-stock items with a user-friendly and accessible procurement system:

There's nothing new here in the principle of what we've done. But we are the first to put the ability to place an order quickly and efficiently in the hands of the people who need to make that order. Materials management works extremely well for the high-volume, low-value items used on a day-to-day basis: it is easy to set re-order limits and define stock replenishment days. However, it is not appropriate or cost effective to have infrequently used and high-value items sitting on the shelf until they are required. This can have a significant impact on cash flow and reduce wastage as items go out of date. For example, a clinician is never going to pick up a £15,000-£20,000 pacemaker off the shelf. We needed a system that could cope with both non-stock and stock items without burdening clinical staff. Moreover, problems can arise because even Materials managers, who are responsible for replenishing stock, are not aware of the day-to-day fluctuations in ward activity. As a result, valuable clinical staff time can be spent looking for stock in other wards if an item suddenly runs out due to out-of-pattern consumption.

The paper chase

Prior to Bradford's supply chain project, there was a paper process for procurement which resulted in multiple hand-offs, re-work, and time spent chasing orders, especially as more than 10 per cent of paper requisitions were illegible, incomplete or incorrect. The typical errors produced by sloppy or faulty paperwork and the lack of upto-date catalogues were overordering, incorrect ordering and late delivery.

The overall procurement process was slow, with some requisitions taking up to 11 days to reach the purchasing department due to delays in approval and internal mail and then 2 to 3 days to process the order. Firefighting took up a great deal of time that could have been better spent with patients. Some requisitioning staff reported that they spent up to two and a half hours each week trying to sort out supply-related problems to ensure that they had the correct items for an operation or course of treatment. Most of these problems were not caused by any inherent complexity in the products being ordered or difficulties at the supplier end, but were due to the poor quality of the requisitions themselves or even because paper simply got lost in the system.

Staff had responded to the endemic slowness of the procurement process by habitually submitting ‘urgent' orders to try and accelerate the process. This practice would delay the order stream while blurring the sense of truly urgent orders, thereby helping to devalue clinical prioritization.

The trust also had to deal with multiple paper catalogues covering the mass of supplies available for requisition. Paper documents are notoriously hard to manage. They replicate with abandon, but are hard to cull. Each department had its own catalogue of items that it would use for regular orders, but these documents were frequently out of date. Even more seriously, many of the departmental catalogues in use did not conform to the trust's policy.

Many organizations have identified the potential costs in staff members buying ‘off-catalogue'. If the organization has struck a deal to buy, say, stationery at one price from one supplier, then ‘maverick buyers' who use a competing catalogue, perhaps by accident, can end up overpaying for their goods. In the case of a clinical environment, the risks of off-catalogue buying are even more serious, as Whatley explains:

Where a trust doesn't have control over its purchasing, staff can order items that they're not qualified to use, or that aren't compatible with the equipment or drugs that are going to be used. You sometimes hear of a clinical incident where somebody used something they weren't trained to use - but what that means is that somebody bought the wrong thing. Different departments are trained to do things in different ways, so it isn't cost-effective to encourage too much substitution. There's a cost in training people to use different products. Not everything is like, say, a cotton wool ball, where there can be an advantage from standardizing. But even then the significant saving comes from reducing the processing costs, not getting a cheaper priced product.

The supply chain project reduced the number of items that staff were able to order from 15,000 down to 10,000. However, the trust did not have an effective means of controlling how the new, consolidated, authorized catalogue was used. Whatley says: ‘Technology helps enforce the right decisions. Without this control, you're just buying the wrong things more quickly.'

Once a paper requisition had been submitted, it was difficult to find out where it was or its status. This added to the time spent chasing orders and also resulted in staff resubmitting orders in case they had been lost, only to end up with a duplicate order later on. Delivery confirmation was slow and sometimes non-existent, resulting in delays in payment and adding to the time staff spent chasing departments for delivery notes. In addition, the trust had no effective management information with which to manage the supplies process.

Atos Origin therefore worked with the trust to implement an e-procurement solution that would eliminate paper and automate the procurement process throughout the organization. The goals of the project were to increase the quality of ordering, reduce the time spent by clinical staff handling supplies and speed up the delivery of goods. At the same time the new system would enforce the trust's purchasing policy and procedures. The trust's chosen procurement processes would be in effect glued in to the system that staff would have to use if they wanted to order any item. The technical requirements for the system included its ability to integrate with a new Oracle Financials installation that was being implemented at the same time, and be amenable to integration with certain supplier systems in the future.

The system would therefore act as a single gateway to procurement for all suppliers, all products and all staff. This was a business-centred approach that avoided inefficiencies represented by the potential alternative of installing suppliers' systems for procurement. Whatley says: ‘We produced a solution that's supplier-agnostic. Very often a supplier will say, 'Use our system to buy our products.' But any supplier system will only address part of what the trust's people need.'

The target user group for the system was large and diverse. The trust wanted to put the power of procurement directly in the hands of responsible staff, whatever their technical specialism or role in the supply chain. Bradford has around 400 designated requisitioning and approval staff in more than 100 departments spread across several sites, with supply requirements ranging from basic stationery to complex medical equipment. The profile of these staff varied throughout the trust. They included both clinical and non-clinical staff, deskbound workers and completely mobile workers, those who were computer literate and those with no experience of computers, and people working on trust sites and in the community.

The trust wanted to limit the number of people who could raise clinical requisitions to designated clinical staff familiar with the products and responsible for their use. This policy reduces clinical risk while making people aware of the costs of the materials that they use. Bearing in mind that clinical staff rightly consider their priority as spending time with patients and not ordering supplies, this requirement posed several challenges to the team.

First, how would they persuade clinical staff to use the system? Clinical staff will always be responsible for raising requisitions for clinical items, but typically they are inclined to scribble their orders on pieces of paper and hand them to office clerks to create the requisition. This saved them a few minutes in creating the requisition, but invariably they spent time later on chasing and sorting out problems due to illegible, incomplete or inaccurate orders. We all have a tendency to put a higher value on present time than future time, especially if we work in highly pressured environments with multiple demands for critical decisions.

The team therefore needed to demonstrate to staff that getting the order right up-front would significantly improve the process, while presenting a solution that made it easy for them to get it right first time. The system would have to be quick to access and navigate. Raising requisitions, tracking them and receipting them would need to be fast, simple and intuitive. The system would have to be accessible to staff that did not have access to a PC or whose work required them to be mobile. Ideally, the system would require minimal user training.

The second challenge was the issue of effectively enforcing the organization's purchasing policy and procedures. As a result of standardizing its product set, the trust had significantly reduced the number of products that staff were entitled to use. However, without an effective control mechanism, the trust would find it difficult to realize the benefits. Whatley says: ‘We can save 3-7 per cent of supply chain costs for an NHS trust by these means. The technology underpins that, and makes sure you get the actual cost savings.'

A solution called WANDER™ procurement

Atos Origin and Bradford analysed these requirements and constraints, and decided to pilot an e-procurement solution that was mobile enabled. Mobile applications, which use pocket or handheld devices connected wirelessly to corporate or public networks, are becoming increasingly popular in enterprises with large populations of mobile workers. However, such applications are usually cost-justified by their impact on the productivity of a specialist group of workers, such as engineers who fix equipment in the field, or salespeople. In such cases, mobile technology helps to spread the benefits of corporate information systems to the periphery of the organization, where people have typically had poor access to enterprise systems. There is no doubt that mobile applications have become fashionable in recent years - if only among systems developers.

Bradford was not interested in using mobile technology for its own sake. Instead, the team recognized that the mobile platform addressed the project's varying needs in an optimal manner. In the first place, providing the application via a wireless network would mean that staff would be able to access it wherever they were on site, regardless of their sedentary or mobile work style. Second, the small screen size and reduced processing power of mobile devices has the beneficial effect of enforcing simplicity on applications developed for them. The team decided to use PocketPC devices, which run a simplified variety of Microsoft's Windows operating system and integrate well with other systems. The PocketPC operating system is very easy to use - users require virtually no training. The devices are sold as consumer items, and therefore enjoy low cost and easy supply.

Finally, the team recognized that mobile applications are becoming increasingly popular in the health sector and that a wireless network deployed for e-procurement could be used by other clinical and nonclinical applications. The mobile e-procurement system - now dubbed WANDER™ - would demonstrate the use of mobile technology in an application that touched every department and grade across the organization. Unlike organizations that introduce mobile applications for specialist teams and then frequently find that they have duplicated functionality and technology spend in several areas, Bradford would enter the wireless world with a truly corporate system that supported a high-profile business process. Future mobile applications would be more likely to use WANDER™'s infrastructure and reuse its development strategy, thus saving unnecessary redevelopment and the creation of disconnected and incompatible systems.

WANDER™ allows requisitions to be raised quickly using trust-approved catalogues. If the requisition requires approval it is automatically presented to the designated approver who is notified by e-mail, otherwise it goes straight to the purchasing department. Purchasing staff then process the requisition and send the order to the supplier. Staff can go online at any time and establish the status of the order and when it is due for delivery. When the item is delivered, the person responsible for receipting can call up the purchase order and confirm delivery against the item. The accounts payable team is then able to check that the item has been delivered before paying an invoice.

WANDER™ therefore automates the entire procurement process, and with its e-mail notification capability it also drives the workflow. Mobile access means that delays in inputting, approving, ordering, querying or receipting requisitions are removed. Now the ordering function can fit efficiently into the stream of events with which each staff member is dealing. It is an elegant solution to the trust's desire to make its clinical staff responsible for their own supply needs which also has the virtue of creating a seamless collaborative process among the many individuals involved in procurement.

Pilot and launch

The team decided to pilot the solution before rolling it out across the organization. The pilot phase would enable the team to assess the effectiveness of its technology choices and iron out any problems with functionality or usability before WANDER™ became the mandated route for all the trust's purchasing activity.

The trust worked with Atos Origin to map the desired procurement process in terms of stages, outcomes and user permissions. The team then selected two pilot areas with varying user requirements. These were the ENT (ear, nose and throat) theatres and the paediatric outreach department. A wireless network was installed and connected to Atos Origin's Managed Service Centre, where the application is hosted, via the national NHS.net network. User permissions were installed so that relevant functions were accessible by authorized users. Finally the standard catalogue items were loaded into the system.

People with responsibility for requisitioning, approving, purchasing and receipting supplies were given up to two hours of training. The training session described the rationale for e-procurement and the benefits of wireless mobility within the trust. Staff were also shown how to use the PocketPCs with which they were issued. The training session was used as an opportunity to make staff appreciate the source of their existing purchasing problems in the paper process and how the automated solution would eliminate these errors once and for all. The team was pleased to note that the very first transaction made on the new system via a PocketPC was from a paediatric nurse with no prior experience of computers.

The pilot lasted three months, during which time the team monitored progress and made minor improvements to the system following user feedback. The trust's supply chain board then judged the pilot a success and gave the green light for its extension to a further 30 areas and 150 users. This extended pilot phase lasted from July2002 to January 2003 when it was agreed that WANDER™ would be rolled out across the entire organization. The trust-wide roll-out commenced in August 2003 and more than 700 staff now have access to the system every day.

Faster and better

The team has been able to measure the improvements brought by WANDER™ and noted particularly how the system has accelerated the procurement process. Speed translates very readily to improved quality of care and greater throughput, which are two of the most important variables used to assess a trust's performance.

The elimination of paper has eradicated errors and the need for rework. Requisition accuracy has increased from 90 per cent to 100 per cent. Meanwhile the time from raising a requisition to presenting it to the supplier has reduced by up to 90 per cent.

Clinical staff are now able to spend more of their time caring for patients rather than concentrating on administrative tasks. Andy Sykes, a team leader in ENT says: ‘The whole requisitions process now takes 2 to 3 minutes whereas, previously, paper-based requisitions could take anything between 15 and 20 minutes.'

The time spent chasing orders has also been reduced due to the elimination of errors and the ability to track orders. For example, staff can now see if an ordered item has been delivered but not yet receipted at its final destination, and if necessary retrieve the item from its current location. Previously delivered items could be held up within the trust's sites and staff would not know they had actually arrived within the organization's control. Deliveries now arrive more quickly at the places they need to be.

The compliance with the trust catalogue enforced by the system has reduced clinical risk while sustaining the benefits achieved through the earlier rationalization of the supply chain catalogue. The wireless mobile capacity of WANDER™ has extended the supply chain to people that would otherwise continue to use paper methods or have to disrupt their work patterns to find a workstation. The team has also confirmed that it is considerably easier and faster to train staff to use the mobile device than desktop PCs.

The benefits WANDER™ offers for the future include the value of its wireless infrastructure as a platform for other clinical and nonclinical applications. The trust is also now well placed to create strategic relationships with suppliers by encouraging them to interface with WANDER™. This puts the trust in the driving seat: rather than electing to take systems created by different suppliers, the trust can ask suppliers to match their e-commerce offerings to the data standards and functional attributes of its organization-wide procurement system.

The final benefit that WANDER™ has brought to the organization is a subtle one, but nonetheless of significance. The provision of a simple, mobile, reliable and policy-conformant application for procurement throughout the trust speaks volumes about the organization's belief in the importance of getting purchasing right, and in empowering its decision-makers to drive the supply of the items they need in order to treat patients. By investing in e-procurement in this very visible and personal way, the trust is demonstrating that what people buy is core to how well the trust performs, both as an economic entity and as a collection of dedicated professionals. Rose Stephens, the chief nurse and director of hospital services at Bradford, is convinced that this solution is having a real impact on the trust's work:

WANDER™ is a simple, practical tool that lets us get on with the job we joined the NHS to do - caring for patients. It is a great example of how technology helps us cut administration and do our jobs better. The greatest benefit we have seen from the supply chain project is in managing our clinical risk. We are seeing real clinical benefits by focusing on a standard range of core products.

Mobile applications are still at an early stage of development, and most that have been developed to date have been aimed at niche tasks or attractive vertical markets such as estate agents or engineers. The Atos Origin team saw that mobile technology could be readily tamed and put to the service of a core corporate function. They chose the mobile channel for delivery because it matched what the trust needs in terms of accessibility, usability and personal responsibility. But the team's technology insights were joined by an appreciation of the challenges facing NHS trusts, especially with regard to purchasing policy. Procurement is one area where it can be easy to throw technology at problems without exploring the context of those problems. A paperless solution may appear to be the obvious answer to slow, error-prone manual processes, but applying a standard commercial solution would not have been optimal for this situation - and could even have been dangerous. The Atos Origin's team experience in clinical settings is driving the firm's formulation of strategy for NHS clients, resulting, for example, in a passionate belief in the support of efficient and accountable non-stock supply rather than a wholesale shift to commercial-style materials management.

That the firm has also made the trust an effective host for other mobile applications is an incidental bonus, but one that will ensure that the organization continues to meet its commitments to the community, staff - and clinical excellence.

For IBM, its 15-year involvement with Wimbledon has seen several generations of technology transition from the laboratory to the marketplace. Its recent work at the All England Lawn Tennis Club has been a useful proving ground for its ‘e-business on demand' strategy, aimed at helping small players make big hits when they need to.

For two weeks every year, millions of armchair tennis fans pray for the rain clouds to avoid southwest London so that they can avidly follow the fortunes of the world's greatest players at the game's most prestigious event. There is little that consultants can do to alter the weather, but consultants from IBM, who have been working with the Wimbledon organization for 15 years, have consistently applied technology to improve the experience of the annual Championships for players, organizers, broadcasters and spectators alike. In recent years the two partners have proved how technologies can transition from the laboratory to the business environment.

Despite the size and fame of the annual Championships at Wimbledon, the All England Lawn Tennis Club is actually best classed as a small business - albeit one that grows to much larger proportions every June. The challenge for the IBM Global Services team based at Wimbledon is that of ramping up the information facilities of a small business to meet the intense demands of the Championships, while not committing the organization to expensive services it does not need at other times of the year. Dealing with a peak of demand that is regular in timing but unpredictable in size has helped IBM develop its ‘e-business on demand' offering, and thereby help other small-and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to rise to similar challenges.

Tennis is a global sport that has grown in popularity over the past decade. While the facilities at the All England Lawn Tennis Club have grown to keep up with this demand, there will always be a finite number of people who can attend as spectators during the two-week Championships at Wimbledon. Now the world's largest annual sporting event, ‘Wimbledon' signifies the grass game to millions of people across the world. During the event, there is a high demand for information from around the world and around the clock. Fans want to follow the matches, the players and the buzz of the event. Some of them will find their needs served through broadcasting networks, while others will want to interact in a more personal way. The Club needs to meet the surging demand for information relating to the event in a way that embodies the Wimbledon experience of quality and attention to detail.

The goal set by the Club with IBM and its suppliers is to ensure that all of the stakeholders involved in the Championships have the information they require to enhance their overall experience of the event. The stakeholders include in-ground spectators, television viewers and the online audience. Players and coaches are also key stakeholders, and their satisfaction with the available information services is a growing component of their overall appreciation of the event. The press, broadcasters and commentators make up another key constituency, as do the officials of the Club itself.

From point played to data displayed

The Championships' information flow begins with shots played on the courts of the Club. Just as efficient information systems located within mainstream businesses aim to capture data at the point of creation, and to capture it only once for whatever uses it may be put to, so the Wimbledon team collects data on each shot as it is played. A group of 48 tennis specialists use laptop and handheld devices to record every detail of every game. These recorders are often players of considerable skill and achievement in their own right, and they use their knowledge of the game to collect and categorize the data correctly. The ‘show courts', or those which are televised, have their match statistics captured in real time and streamed to a local area network (LAN). The outside courts do not require real-time statistical information so details for these matches are captured using an IBM Workpad and uploaded into the central database after each match.

The team captures around 120,000 statistics on every day of the event, and these are stored in a central database. The database in turn feeds a number of users. For example, scores and detailed statistics gathered from courtside can be displayed by the BBC as a graphic to support television coverage of the match and commentators' analysis. The distinctive graphics have been designed over several years by the All England Club and the BBC, guided by IBM consultants in graphics design. Any combination of over 90 graphic elements can be called upon at any point in a match. The systems generate the required graphic, tie in the data and display it to the BBC producers, ready for live transmission at their discretion.

In addition, each commentary position is equipped with a system that gives detailed analysis of the current match by player, match fact or set. This system provides a wealth of information for the match commentators, adding hard factual evidence to their own expert match analysis.

Some foreign broadcasters also need match statistics in real time to augment their coverage. The project's central database is replicated to individual data repositories as and when any updates occur. This means that any internal design changes required to the database, or changes to information required by an individual client, can be made independently of each other. This approach facilitates change across the client base and removes the need for discussion and compromise within a complex change management process. Each broadcasting client gets, in effect, a tailored service while the underlying data remains identical and authoritative for all users.

BBC Interactive uses this facility to provide key match statistics to users of its digital TV service. This service gives the viewer the opportunity to choose from any of the show court matches in progress and to view the key match stats alongside live coverage.

The team has also attached its data streams to a match information display (MID) within the ground. The MID is a large screen that displays up-to-the minute scores on matches in progress, enabling anyone on site to see the latest information at a glance. Other information can be displayed such as player biographies and animated display sequences plus general announcements from the Club. A second display was added in 2003.

Looking beyond the ground and the broadcasting community, the team also uses the data it collects to drive its public Web site. The 1995 Championships Web site was the first global sporting event to be put on the World Wide Web and since then the online audience has grown exponentially. In 2003 the site had over 4 million unique users generating 231 million page views and 27 million visits. The average time spent at the site by visitors, sometimes known as ‘stickiness', was 2 hours 11 minutes.

A key element of today's www.wimbledon.org is the real-time scoreboard that shows scores correct to within a few seconds of the point being played. In 2002 the scoreboard was also voice-enabled in five different languages.

Other elements of the Web site include interactive cameras known as ‘Slamcams' which can be controlled by the users. There are also full player biographies and historical match highlights. The site also streams Radio Wimbledon and The Wimbledon Channel, a daily live studio presentation, with eight hours of video, match analysis, features about what is going on at Wimbledon, plus player and celebrity interviews. The site also contains an online store.

While the Web has become a key focus of the team's service to its global audience of interested individuals, the team has also branched out into other delivery channels. Information can be supplied by SMS (text message) to mobile phone users, and to special WAP (wireless application protocol) pages to phones with browsers. There is also an interactive TV service.

Serving the players