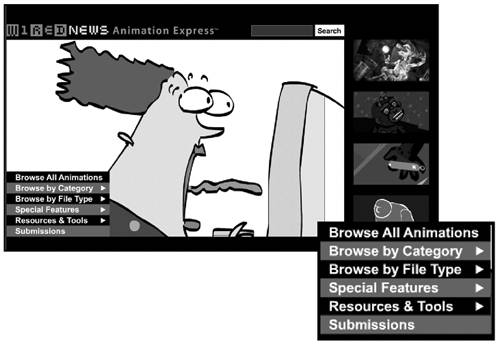

5 raging debates in web design 1. to splash or not to splash? A splash page is the introductory page usually animated that precedes the real front door to a web site. The animation plays, and then the user is automatically "pushed" to the next page (the real front door). The debate: Designers are divided over when and if the splash page is a good idea. Proponents view splash pages as a chance to grab users when you have their full attention and submerge them in the world of your site (without bogging them down with all the navigation and practical functions of the front door). Detractors view splash pages as a poor imitation of TV and a huge waste of bandwidth and time. A balanced perspective: "I like the theory of having a foyer an entryway that provides a transition and establishes where you've arrived," says Nadav Savio, a principal at Giant Ant Design. "But not that many web sites can afford that transition. In the majority of cases, the purpose of a web site is to connect people to some kind of information, and a splash is often going to get in the way of that." 2. to flash or not to flash? Macromedia Flash is a plug-in technology that brings animation and interactivity to a web page. When a large portion of the page is smoothly animated, Flash is usually involved. The debate: It's hard for designers to reach an agreement about Flash, because it's enabled some of the most exquisite work on the web, and some of the most excruciating. At its worst, Flash promotes poor navigation, non-standard interfaces, annoying gratuitous promotions, and inaccessible content. At its best, Flash is used to create entertaining animations, wondrous art, engaging multimedia presentations, and interactive navigation systems that wouldn't be possible with regular HTML. A balanced perspective: Like any technology, Flash should be used where it makes sense and where it best solves a problem: to animate, to show motion, to incorporate sound, and possibly to facilitate complex transactions within a single screen. The site for Def Poetry Jam decided to splash and Flash: This animation executed in Flash introduced the site when Def Poetry Jam's Broadway show opened in 2002.  3. scrolling vs. paging Frequently, you'll have more information to put on a single page than can possibly fit. Should you put all the information on one page and make users scroll down, or should you divide the content into multiple pages and make them click through? The debate: There's a lot of disagreement about this question: How deep or long should a web page be? How far down should a reader be expected to scroll? Some take the stance that pages can be endlessly long: That the goal is to minimize the number of downloads, and it's better to cram a lot of information on one page than to require users to click again (because users "hate to click"). Go ahead and pile it on: Let the users decide when they're tired of scrolling. Another perspective favors shorter, more concise pages and multiple opportunities to click onward (because "users hate to scroll"). These page breaks are psychological as well as practical they help mark users' progress and provide a needed mental and visual break. A balanced perspective: As is so often the case, the best approach probably lies in the middle. Users will continue to click and scroll, so long as they're finding what they're looking for. A number of studies have shown, however, that users prefer to click. When given a choice, for example, between 10 search results per page and 50 they'll choose 10. 4. to clutter or not to clutter? Many web sites have a problem with clutter: More things need to go on the front door than can comfortably fit. Is it OK to clutter, or should you pare down? The debate: Most graphic designers love white space. They like to leave breathing room around elements on a page. And the web-wide inclination to pile things on a site's front door runs counter to their best judgment. "It's my opinion that most sites are just trying to cram too much on the page, too high above the fold," says Doug Bowman. "I think that's actually been to the detriment of the web." "There's no white space on the web anymore," he continues. "Real estate is at such a premium that people don't think about using space to help set off certain elements." But some site owners will tell you that clutter's effective even if it is ugly. "We have this constant debate about clutter," says Adam Berliant, a group manager with Microsoft who has overseen both MSN.com and the WindowsMedia sites. "Less clutter is easier to look at. It's easier on the eyes. But that forces the web producer to try to come up with clever ways to make content available through fewer links." "Suddenly, I need something that says 'Entertainment' to represent everything from games to entertainment news to radio," he says. "But if I just link directly to games, news, and radio, guess what? More people click. So while clutter is certainly not as attractive, it often means more usage. And that's why this web site exists. It exists to be used. It doesn't exist to be pretty." A balanced perspective: The appropriate level of clutter seems to depend a lot on the site. One way to find the right balance is to test what happens on your site when you're pared down vs. cluttered up. Does your site use go up? Then it's probably a good thing. Does it plummet? Well, then, it's probably not a great idea. |