Resolving Strategic Conflict

Ensuring the success of the organization's business strategy should be the number-one priority of every senior team. Strategy is an organization's self-definition of the future. Disagreement among senior players about future product and market scope and emphasis, key capabilities, financial targets, and growth expectations creates fault lines among senior-team members that can undermine the foundation of the business. Since this book is not about how to formulate strategy, the question we will examine is: How can a senior team resolve the conflict that keeps it from delivering the results its board and stockholders expect?

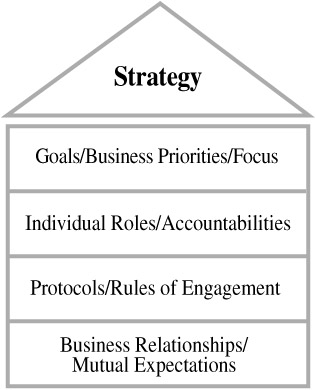

Effective conflict management begins with alignment. To operate at peak performance, a senior team must be aligned, or reach agreement, around four distinct factors. (See Figure 2-2.)

Figure 2-2: Key Alignment Factors.

First, strategic goals and the key operational goals that flow from them must be clear, specific, and agreed-upon. Second, the roles of the team members need to be carefully delineated so that they know exactly what they are responsible for and what they are authorized to do. Third, protocols or ground rules must be established to guide group behavior. Finally, interpersonal relationships ”the range of personal styles that members of the team adopt when interacting with one another ”must be understood and managed.

Let's examine how, by becoming aligned around each of these factors, a senior team can replace unresolved conflict with healthy disagreement.

Goals/Business Priorities/Focus

Not every senior management team is as misaligned as that of the Canadian oil company. Johnson & Johnson's senior team is a notable example of a tightly aligned, highly effective leadership group.

Johnson & Johnson (J&J) is a portfolio organization consisting of 195 companies that make up the health care giant. The companies, or business units, are organized into approximately twenty franchise groups with products as disparate as vision, skin, and feminine health care; minimally invasive surgery; wound management and closure; and drug therapies such as over-the-counter analgesics, anti-infectives, and painkillers.

Because each franchise is unique, each year J&J's senior team asks the leaders of each franchise to develop their own strategic plan, which is submitted to the executive committee for review and approval. Once the plan is approved, it is up to the individual franchise to translate the strategy into operational goals and action plans in each of its businesses, at every level.

How does J&J manage the centrifugal forces that are typically at play in a portfolio environment? According to Michael Carey, corporate vice president of human resources for J&J, the franchise strategies are tied together by clear, common goals and values, which minimize the possibilities for misunderstandings and misalignment. These goals are articulated in two places. The first is the parent company's Statement of Strategic Direction, which says that it will abide by the ethical principles of its Credo, capitalize on its decentralized form of management, and manage for the long term . The second is a list of four imperatives that have been identified by the executive committee. These imperatives of innovation, process excellence, e-business, and flawless execution are the themes around which J&J expects each of its businesses to pursue its individual strategy.

And, just as each franchise keeps the statement of strategic direction and the four imperatives in mind as it develops its strategic plan, so must the business units within the franchise as they develop theirs. Carey cites an example:

Ethicon is one of the cornerstone companies in our wound care franchise. Its base business is wound closure: sutures, stapling, adhesives. Wound care has declared that its goal is to become the innovation leader in its category. For the franchise's strategy to succeed, the Ethicon team must be committed to the same goal. For example, R&D might suggest pursuing the me-too solution of using synthetic skin to close wounds. Marketing might respond with, "No, we need to be more innovative. We need to develop sutures and staples that cause less trauma as they pass through the skin, that produce less swelling and promote faster healing, less chance of infection, and fewer doctor visits ." If the team is truly aligned around the goal of becoming an innovation leader, the choice should be an easy one. That's how having clear goals, from top to bottom, reduces the potential for in-fighting and competition among functions.

Philip Morris U.S.A. (PMUSA) is another example of a strategically aligned organization. PMUSA's senior management team focused everyone in the company around a clearly stated mission: "To be the most responsible, effective, and respected developer, manufacturer, and marketer of consumer products, especially products intended for adults. Our core business is manufacturing and marketing the best-quality tobacco products available to adults who choose to use them." The team then translated this mission statement into specific, achievable strategic and key operational goals.

These actions won the respect of Joe Amado, PMUSA's vice president of information services and chief information officer. Amado felt that the top team had provided his department with unambiguous guidance for decision making.

Unfortunately, Amado was less impressed with the stated mission of information services, which was "to transform the way people work." What linkage did this have to the company's mission statement? He was even more troubled by the vagueness of the charter and his inability to tie it to his customers' needs.

Complicating matters was the fact that IS was a department in flux. It had gone through numerous restructuring efforts, under a number of leaders, before Amado came on the scene. Amado approached his boss Roy Anise, the senior vice president of planning and information, with the idea of taking IS through the same type of alignment that had been done for Anise's own senior team. Anise agreed.

Amado assembled his direct reports ”IS account directors for operations, finance, HR, marketing, and sales ”and three individuals who provided services to them ”the chief technology officer, the head of shared services, and leader of the project-management group. He also invited to the alignment session four senior leaders within the IS organization who, although they did not report directly to him, provided vital support to his senior team.

In their first alignment session, Amado and his team made reasonable progress on issues related to interpersonal style and accountabilities, but their lack of common goals soon became apparent. To move ahead, Amado's team needed to rethink its mission.

After several intense strategy-setting sessions, the group came up with a new mission statement: "The role of information services is to maximize our clients ' contribution to the PMUSA mission by optimizing their use of information technology for business success."

With this new, clear mission in mind, Amado and his team moved to become more customer-centric. Knowing that structure should follow strategy, they decided that the best way to accomplish this was to create customer teams , so that each internal customer ”marketing, finance, sales, operations, or HR ”would have its own group of IS professionals who would be dedicated to helping it optimize its use of information technology (IT) to maximize its contribution to the PMUSA mission.

The customer teams were formed , and each, in turn , went through its own strategy session, setting goals consistent with the larger IS strategy and making specific action plans to help its internal customer maximize its contribution to the PMUSA mission. At PMUSA, there is a clear line of strategic sight, from senior management to IS and then to IS's internal customers.

Individual Roles/Accountability

Ending the Turf Wars

People often gripe about having too much responsibility, but try to take some of it away and you'll be amazed at how hard they fight to hold on to the status quo. Most executives equate responsibility with power ”and both with pay and glory . This explains the frequent tugs-of-war that arise when corporate roles and responsibilities are not clearly delineated.

When the senior team fails to clearly delineate which function is responsible for which steps, especially in organizations where the value chain is complex, open warfare often ensues. Paul Michaels is regional president, America, for Mars, Inc., the consolidated domestic unit of Masterfoods USA's pet, snack , and food divisions, previously known as Kal Kan, M&M/Mars, and Uncle Ben's. Considered a creative thought leader, Michaels has led teams at some of the nation's leading consumer packaged goods companies, including Johnson & Johnson and Procter & Gamble. He recognizes the importance of individual roles and accountability. Based on his years of experience, Michaels describes some of the turf battles that typically occur when a company fails to make accountabilities clear:

Manufacturing is driven by efficiency and likes to perfect one product spec for all customers. Sales, on the other hand, is under pressure from significant clients to provide customized products. The VP of sales promises the customized products, and his or her counterpart in marketing encourages that group to begin advertising the variations. Or R&D comes up with a complicated design that strains manufacturing's resources. As complaints emerge, the VP of manufacturing makes the call to change some of the specifications. Everyone is pulled in different directions, and, before you know it, it can be all-out war.

The way to deal with this lack of alignment is to hold a formal session on the subject with the senior team. Before beginning the alignment session, it is useful to ask participants to rate the team's performance in several areas. Ask the following two questions: "How clear are you about your role/accountability on the team?" and "How clear are you about the other team members' roles/accountability?" Many CEOs and presidents are surprised and easily frustrated when they learn the scores on these questions, which are generally low. A typical retort is: "What do you mean, the head of sales isn't clear about what he does? He's in charge of sales. What's unclear about that?"

What these leaders fail to realize is that none of their team members operate in a vacuum : They are constantly bumping up against one another, passing the baton from one to another. Yet, they may have never sat down and discussed what they expect from one another at these intersection points. In many cases, the alignment session is the first time senior-team members have ever addressed these issues together.

We suggest probing further. During an alignment session, ask team members to define their job for the rest of the group, to list the activities that they carry out and the results that they are responsible for, to describe how they believe their job is perceived by other players, and to identify the gaps that exist between themselves and the other team members. Then record their responses on a matrix that is visible to the entire team. As each executive's data is added, the disconnects become increasingly apparent. The discussion that follows often results in an entirely new model, with new intersection points, on which everyone can agree.

In the course of clarifying their strategy, it became apparent to Joe Amado and his senior team that they were also unclear about their respective roles and responsibilities. For instance, Amado's direct reports, the five directors, had never really been held accountable for a specific business area, such as operations, marketing, sales, finance, or HR. Several wore multiple hats. The technology director, for example, was not only chief technology officer, accountable for all the technology across PMUSA, but he was also accountable for providing all the technology solutions to the large department known as operations. Both marketing and sales, which at the time were implementing an IT-heavy initiative, came under the umbrella of the marketing director.

The team's next step, after clearly defining each of the customer groups it was committed to serving, was to assign a director to each group. Amado explained,

I now have five directors, and each one is aligned with a specific business area. That's their unique role. They have no other role but that. It's very clear to them that their performance will be judged by the business value they add to that area, the level of customer satisfaction in that area, and the employee satisfaction among the individuals that work for them.

Amado has also put in place a system to measure the results achieved by each director and his team. His scorecard is a simple, yet highly effective measurement tool. It adds discipline to the equation and reinforces responsibilities and accountability. Each of the five teams maintains a one-page "eye chart" that lists all the projects it is currently working on. Each project is then divided into three aspects: scope (i.e., the requirements for the project, what must be done to deliver business value), budget, and schedule. Progress in each area is represented by a color -coded symbol, similar to a traffic light: green indicates that it is safe to move forward; yellow means that there are some issues, and caution is called for; and red means you better stop and think about what you are going to do next.

In a large area, such as operations, IS may be involved in as many as fifteen projects at any one time. The scorecard allows Amado and his operations director to instantly assess the team's progress on all of them. If a project is falling behind schedule, the yellow symbol serves as a trigger for discussing possible solutions: Should some of the team's resources be diverted from another project to help out on this one? Is the delivery date realistic, or should it be reconsidered?

Amado's eye chart is designed to measure his teams' performance in the first category, which is the business value they add to their assigned area. But he is also holding them accountable for results in two other areas: customer and employee satisfaction. These results are also being measured, with questionnaires being sent to both groups on a regular basis and the responses tabulated and factored into performance evaluations.

Since aligning his team around a new strategic vision, Amado has noticed many changes in their behavior ”as well as in his own. Much of the recurring, energy-draining conflict that once existed has finally been resolved, and the team members have become much more adept at handling new disputes when they arise:

Complaining to others about someone else, in staff meetings and one-on-one conversations, has stopped . Now, when there are conflicts, people go right to the individual they are having a problem with and resolve it themselves. I am not getting involved in all of the minor issues that I used to, because they don't come to me anymore. They know they are accountable for solving these problems. Now they come to me only with the strategic issues, those that relate to the running of the business or issues in the marketplace .

Stopping the Buck

While amassing power is a familiar pastime in many senior management teams, so is passing the buck. And when it isn't clear who is accountable for what, that is rather easy to do.

At one manufacturing company, a new president came on board in April 2000. The company's operating plan for 2000 had been put into place in January, under his predecessor, and was predicated on the amount of product that had been shipped in 1999 rather than on what had been sold by retailers. The problem was that 1999 was an anomalous year, during which the threat of Y2K snafus fueled an unusual buildup of inventory. In addition, the company's major competitor was in bankruptcy, which caused it to project increased sales. When the new president arrived, retailers still had large stocks of excess inventory, and the company was operating under a plan that was inflated by $75 million.

The new president needed to remedy the situation, and quickly. But he could not do it alone; he needed the cooperation of the various functions to develop and execute a new plan. This was not easy to accomplish, however, because of the way in which planning had always been done and the resulting reluctance of the players to take responsibility for a new plan. He describes the situation in these words:

Everyone on the senior team should have been involved in putting that plan together. But, in fact, only three or four people had provided the data for the original 2000 plan. The others hadn't been asked for their opinion, and they hadn't volunteered it. There were several individuals on the team who could ”and should ”have raised a red flag and said, "Folks, should we not look at what sold through?" Obviously, the VP of sales could have done that; the forecasting guy could have come forward and said, "Wow, we are doubling our sales potential here. What is going on?" But no one considered it his or her role, and when performance reviews were conducted , no one could be held accountable.

In light of these needs, the alignment process for the new president and his team emphasized strict accountability. Now, when the company puts together an annual operating plan, the three or four people who are responsible for projecting sales growth are expected to be able to fully explain to the rest of the team the process by which they reached the numbers . And they are questioned unremittingly until their peers are satisfied that they have covered all the bases.

Along with this new accountability, the president has instituted a new decision-making model. Before making any major decision, the team comes to an agreement as to how it is going to be made: unilaterally, collaboratively, or by consensus. Who will be consulted for information? For opinions ? Who will make the final decision? And, who will execute it? Today, whether the senior team is considering a new product introduction, thinking about increasing manufacturing capacity, or contemplating the consolidation of functions, this decision-making process is adhered to.

One of the company's vice presidents gives this hypothetical example of how a consultative decision might be made under the new regime :

Let's say that next year we make a decision to freeze salaries, across the board, for four months. Sam [the president] would say to me, "Take the lead on this," and I would work with Tom, our CFO. But other senior-team members might express the desire to be on the team with us. To them, Sam would say quite clearly, "You can provide input, but Margaret and Tom have the responsibility for making the decision. And once the decision has been made, everyone on the team will get behind it, whether they agree or disagree ."

Protocols/Rules of Engagement

Clarity of goals and roles will only get you so far. Protocols for resolving conflicts ”think of them as ground rules for behavior ”both within the team and in its interactions with others, are the third key element in the conflict-management equation.

Team-Based Protocols

At one Johnson & Johnson subsidiary, the president proved to be an adept conflict manager. Cathy Burzik, president of Ortho Clinical Diagnostics, Inc., had her top team lay out "rules of engagement" for itself that covered everything from depersonalizing issues to keeping discussions focused on actual behaviors and what was actionable , rather than on a weather report-type of commentary that did not specify the behavior that needed to be modified or changed.

At Johnson & Johnson and elsewhere, teams have found the following protocols especially efficacious in conflict management:

-

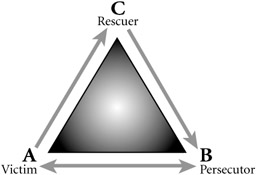

Don't triangulate. Triangulation entails bringing an issue to a third-party rescuer for resolution. Lois Huggins, former vice president of HR at Bali Company and current vice president of organizational development and diversity for Sara Lee Corporation, explains that triangulation is an attempt to avoid responsibility by using a surrogate to handle an issue that should be resolved head-on between two people. Figure 2-3 illustrates the concept of triangulation.

Figure 2-3: The Triangulation Trap.

"When one executive on the team had an issue with another team member, he or she would often go to Chuck Nesbit (Bali's president), rather than deal directly with that colleague," Huggins says. "Chuck would then become involved and assume responsibility for getting resolution."

In another case, a member of the senior team of a property management company had outstanding technical knowledge of construction and had been with the company for many years. He had a close relationship with the president, and whenever he had an issue with another member of the team, he took his complaint straight to the president's office. The president continued to allow this dysfunctional behavior, giving the excuse that, "He's a quirky guy, but he does great work, and he was there for me in the early days."

Triangulation continued until the team went through an alignment. During the session, other members of the team expressed their displeasure with this individual's continuing attempts to co-opt the president. The president listened and then agreed that he would no longer put this person's needs above the good of the group. He promised to stop fostering this person's triangulation efforts, and he has kept that promise.

Paul Michaels is another leader who recognizes how crucial effective conflict-resolution skills have become for today's successful executives. It is a necessary skill that he fosters within his teams. He encourages direct resolution between executives with opposing points of view, without his involvement. When an executive comes to him with a complaint about a peer, Michaels insists that the complainant meet directly with that person to resolve the issue. Only if this proves ineffective will Michaels step in to coach the executives through the issues. Michaels's insistence that the parties in conflict remain accountable not only avoids the pitfalls of triangulation but also provides those involved with an important and valuable learning opportunity.

-

Don't recruit supporters to your point of view. We all know people whose main mission in life seems to be advancing their own cause. For them, life is a zero-sum game. They are always looking for opportunities to win people over to their side, and take the attitude that "if you're not with me, you're against me." They make their private disagreements public by badmouthing anyone who dares to contradict them.

This form of third-party recruiting is contrary to effective conflict management: it is not conducive to open, candid discussion; it does not result in positive behavior change; it tears apart, rather than unites, the team. Ban it!

That does not mean one member of a team cannot serve as a sounding board for another member in need of advice about a third team member. But, in doing so, the aim must be to enlist a sympathetic ear and seek counsel, rather than to recruit additional muscle to further a pet cause.

A corollary rule relates to the sounding board. He or she must hold the individual seeking advice accountable for either dealing directly with the conflict or letting it go. Furthermore, the person seeking advice must report back to the sounding board about how the issue was resolved.

Some senior teams have developed strict procedures relating to third-party involvement. At Arnott's Biscuits Limited, Campbell's largest Asia-Pacific division, president John Doumani and his senior team devised the following protocols for escalating conflict:

-

Individual issues will be raised from member to member for resolution.

-

If there is no resolution, the members involved can choose (together) an appropriate third-party mediator. The first person they should consider is the team's facilitator.

-

If no resolution, the issue is to be escalated to the team mentor, who may advise or be a source of input to aid in the decision.

-

Team members have the right to escalate an issue decision to the full team. The mentor should assist the team as necessary prior to escalation.

Whether it falls to the team leader, the team facilitator, or the full team to resolve intrateam disputes, it behooves the team to act quickly, which leads us to another important protocol.

-

Resolve it or let it go. The longer conflict remains unresolved, the greater the chance that it will metastasize, spreading its poison throughout the team. To cut off conflict before it spreads , some teams adhere to a deadline of twenty-four or forty-eight hours for conflict resolution.

When two members of a team have an issue between them, the team leader gives them a deadline to resolve it. If, at the end of that time, they have not been able to do so, they are expected to drop the issue completely and move on.

-

Don't accuse in absentia. Even an accused felon has a right to hear the charges against him and to defend himself in open court . So should every member of the senior team. If, during a team meeting, someone brings up an issue that involves another member who is not in attendance, the discussion should stop immediately. The team owes it to that person to postpone further debate until the absent person can be heard from.

-

Don't personalize issues. John Stuart Mill once observed that the key to progress is to let all ideas start off even in the race. Eventually, the truth will prevail. In business settings, differences of opinion and viewpoints have a way of stimulating new ideas and strengthening outcomes , provided the discussion can be depersonalized.

One booby trap to avoid might be called the genetic fallacy, which assumes that an issue stems from the inherent animosity of the person or group expressing it. The president of one midsize financial institution had a vice president of sales on his top team who felt that anyone who interrupted him during a meeting was, in effect, telling him to "shut up." Often, the interruption was merely an attempt by another person to open up the discussion. Even after the team worked out a signal to politely interrupt the talkative executive, he continued to feel slighted. Eventually, he left for less intrusive pastures.

A senior executive who has been far more successful in depersonalizing conflict is Campbell Soup's John Doumani. Of depersonalization, Doumani says that:

What it means to me personally is that the issues that we are dealing with are all about the job; they should be dealt with in the context of the job. So if people have an issue with me about the way I do my job, that's not an issue with me as a person. It doesn't strike at the core of who I am. It's feedback about the way I do my job, so I don't take it personally .

It is important to learn, both when giving and receiving feedback, how to maintain a depersonalized position. On the side of the person who is providing the feedback, whether to a direct report in an annual performance review or to a peer in a team meeting, this means stating your concerns in terms of observable behaviors, not feelings. Instead of using formulations such as, "I'm disappointed in your performance," or "You've got to improve your attitude," stay focused on specific behaviors that the person can focus on improving. Stating that "Your department's productivity dropped 7 percent this quarter," or "I have called you three times to set up a meeting, and you haven't returned my calls," is likely to be met with less defensiveness and result in more positive action.

If you are the recipient of feedback from your boss, your peers, or your direct reports, try to follow John Doumani's example: Remember that it is about the way you are doing your job, not your worth as a human being. And remember that it works both ways: If you feel that they are not stating their concerns in a depersonalized fashion, ask them for more objective measures of your performance and for behavioral evidence related to those measures.

Depersonalizing is not easy. In fact, learning to look at a workplace issue as a business case is one of the hardest things that executives must do. But it often brings big payoffs. Peter Wentworth, vice president of global human resources for Pfizer's consumer health care division, believes that the ability to depersonalize conflict goes hand in glove with the ability to come up with creative solutions to business problems.

Wentworth believes that one of the positive byproducts of conflict is that you have the opportunity to hear everyone's side of the story, to look at the same situation from several different perspectives, and, after all the points of view have been expressed, to make a more informed decision ”but only if you can depersonalize.

If, on the other hand, you persist in interpreting other people's suggestions as threats to your position or attempts to expand their territory at your expense, you will never reap the benefits that come from adopting an unbiased viewpoint.

-

No hands from the grave. Lee Chaden is senior vice president of human resources for the Sara Lee Corporation. Before assuming this position in August 2001, he ran the corporation's collection of eight or nine European apparel companies, a $2 billion business headquartered in Paris.

Each of these companies was actually a freestanding business that often competed with the others in the marketplace. In his early days as leader of this group, Chaden recalls that he would walk out of a meeting with the leaders of the companies believing that resolution on which styles each one would offer in a given country had been reached, only to receive a frantic telephone call from one of them a few days later accusing another person of violating the agreement.

As soon as Chaden became aware of the delayed disagreements and second-guessing, he asked his executive committee to establish a no-hands-from-the-grave protocol. For example, one contentious issue facing Chaden and his team related to some of the Sara Lee companies wanting to copy designs from one another to sell to private-label customers. Chaden might argue that such copying should not be allowed until six months after a product launch, since that is about the time it would take the competition to copy the styles. The private-label advocate, on the other hand, might argue that it takes less time than that, and so on.

The executive committee did not leave the room until a firm agreement had been reached on the issue and recorded in meeting minutes. There was to be no second-guessing and no ex post facto finessing ”in other words, there would be no hands from the grave.

Another strong proponent of the no-hands-from-the-grave protocol is Manuel Jessup, vice president of Sara Lee Underwear, Sara Lee Socks, and Latin America North for Sara Lee Corporation. Referring back to his hypothetical example of deciding to freeze salaries even though many senior-team members disagreed, he added, "Some people may walk out of the room and continue to complain about what we did. They want us to go back and revisit our decision. To them I say, 'The train has left the station, and it's not coming back.'"

Protocols Beyond the Team

In the manner in which members of the senior team are constantly interacting with one another, they are also in constant contact with the functions they represent. Many of the issues that arise in their meetings cannot be resolved without the input of people in their function ”that is, sales problems require the expertise of national and regional sales directors; those who conduct market research need to be consulted before major marketing decisions can be made, and so forth. How is this information to be captured and conveyed to the senior team? How will functions not represented on the team make their voice heard? Protocols are needed to handle these and other extra-team issues.

In this area as well as that of team-based protocols, Arnott Biscuits has developed a set of clear, specific protocols:

Beyond the Team

-

The team's functional representative manages the issue back to the function for decision, clarification , information, or advice.

-

The team mentor might assist with the resolution of team versus function issues. The process for resolving these issues will be carried out according to the internal team protocols.

-

The functional representative responds to the team on issues with any supporting evidence/expertise.

-

The team facilitator ensures that issues from those functions that are not represented on the team are raised to the team.

Communication Protocols

Once the senior team has embarked on the conflict-management journey, a number of decisions relating to the rest of the company need to be made. Most senior-team alignments take place off-site, and when the team members return to the workplace, their direct reports often have questions about what they have been doing. How much information about the team's alignment efforts should be shared? Who should share it? When, and in what form? Before going back to the so-called real world, the team needs to develop protocols ”a party line, as it were ”to govern its communications with the rest of the organization.

A Final Word on Protocols

Protocols must be embedded into a company's view of "how business is done around here." To ensure that the team continues to subscribe to its protocols, make certain they are written down and circulated. Keep them posted in the room where the senior team meets. And revisit them periodically, as a group, to assess whether or not they are being observed and if additional protocols are needed to support the team in its conflict-management efforts.

Business Relationships/Mutual Expectations

How well a team works to align its goals, roles, and protocols speaks volumes about the interpersonal relationships among its members, which is the fourth key element that must be aligned within senior teams. These relationships are often the holding pen of conflict. In dysfunctional teams and organizations, it is where silo thinking and subterfuge surface.

In Chapter 1, we discussed the roots of conflict: the deepseated beliefs that have been ingrained over a lifetime, the resulting core-limiting beliefs and going-in stories that predispose people to certain behaviors, and the range of communication styles that characterize employee interactions. We outlined the three basic styles on the behavioral continuum: nonassertive, assertive, and aggressive . To recap:

-

The nonassertive individual, in effect, says, "I've got needs and so do you, but I'm not telling you what mine are. And if you don't guess them, I'm going to hold it against you." The nonassertive individual is Mount Saint Helens waiting to erupt.

-

At the other extreme, the aggressive individual proceeds on the basis that "I've got needs and, at best, so do you, but mine count more." This is the schoolyard bully in business attire .

-

In the middle are assertive individuals, who recognize that both parties in a conflict situation have needs and strive for a negotiated settlement . This is the effective conflict manager.

Each behavior on the continuum has payoffs, and each exacts a price. For the nonassertive executive, the payoff is avoiding arguments and coming across as a team player. But the price is steep in terms of unmet needs and diluted effectiveness.

Aggressive executives often get their way and benefit from the charisma of machismo. They pay the price, however, in alienating others, closing down input and feedback, and failing to gain commitment, especially in the new knowledge-based organization.

Although being assertive forces compromise and takes patience and time, it has all the benefits of a win-win approach.

Training in conflict resolution involves understanding the payoffs and price of each behavior on the continuum; demarcating the boundaries of nonassertive, assertive, and aggressive behavior; and learning how to avoid crossing into the extremes. Knowing oneself is the first step in the process.

Eliminating Blind Spots

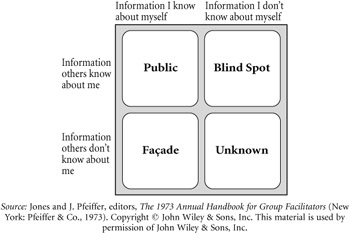

"Know thyself " is a time-honored injunction. Conflict management situations require achieving a balance between knowing yourself and deciding what and how much to reveal to other people. The Johari Window [2] depicted in Figure 2-4 is a graphic representation of the various ways in which we share information about ourselves with the outside world.

Figure 2-4: The Johari Window.

While we are not advising showing home movies of your soul to colleagues, the more information about ourselves we share with others ”the more of an "open book" we strive to be ”the less likely that we will find ourselves in conflict with others. When we choose to keep our thoughts, beliefs, and feelings hidden, we sow the seeds of conflict. By maintaining a false faade, we set ourselves up to be misunderstood. Similarly, when we avoid looking at ourselves objectively, the blind spots that we develop become a breeding ground for disagreements.

One of the biggest challenges we face in life is, as Robert Burns described it, "to see ourselves as others see us." It takes a great deal of skill ”and courage ”to look at ourselves through the eyes of others. It takes even more of both to modify our behavior based on the feedback they give us. If we are serious about resolving the conflict that hinders us, however, it behooves us to eliminate our blind spots, particularly those that relate to our communication style.

We can only get a true picture of the way we interact with others by being open to their feedback ”by soliciting from them the information they have and we do not. This is what sociologist W.I. Cooley calls "the looking-glass self." It is the reason that the exercise that we described in Chapter 1 ”where each person assesses his or her style, then other team members offer their opinions ”is so useful.

Remember Dan, the executive who saw himself as assertive but not aggressive? Feedback from his fellow team members made Dan aware of a large blind spot in his assessment of himself. With this new knowledge about himself, Dan began to realize why the air often became thick when he entered a room and why many of his colleagues went on the defensive as soon as he began talking.

The next step was for Dan to begin moderating his behavior ”changing his position on the continuum. He made a contract with the female executive who had revealed exactly how intimidating she found him, promising to be less aggressive during their interactions. She, in turn, promised to speak up when she felt intimidated rather than keeping her feelings pentup and allowing her resentment to fester.

The ultimate goal when it comes to business relationships is for everyone on the team to be assertive. People who are nonassertive, for example, must learn how to protect their boundaries and express their agenda without crossing the line into aggression. The aggressive individual, by contrast, must learn not to violate the boundaries of other people. Chapter 5 will address the skills executives can cultivate to facilitate their move along the continuum.

[2] "The Johari Window: A Model for Soliciting and Giving Feedback," The 1973 Annual Handbook for Group Facilitators , University Associates, 1973, pp. 114 “120.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 99